Introduction

In the mainstream political economy literature, considerable attention has been paid to the political and economic implications of democracy, left-wing authoritarian and totalitarian rule (Przeworski and Limongi 1993; Przeworski et al. 2000; Acemoglu et al. 2019; Mukand and Rodrik 2020). Many theorists of this tradition believe that party strength or majoritarian rule in the parliamentary form of government makes the ruling party relatively independent from institutional constraints to pursue policies which are conducive to economic growth (Bizzarro et al. 2018; Kitschelt and Wilkinson 2007; Simmons 2016; Simmons et al. 2017). These studies overemphasize the narrow version of economic development, i.e., GDP growth, and in a way consider the role of majoritarian governments crucial for implementing policies that foster growth. In this tradition, little attention has been given to the economic consequences of right-wing authoritarianism, and more importantly to the alliance between right-wing authoritarianism and neoliberal statism. In addition to this, the problem of the mainstream analysis of political regimes and their economic consequences also lies in its nonchalance toward neoliberal ir(rationality) 1 and class analysis as well as the distributional consequences of the alliance between majoritarian right-wing parties and neoliberal forces.

In contrast to these studies, the present article argues that if the economy and politics of a nation are ruled by neoliberal (ir)rationality, then the developmental and distributional outcomes of such a rule are not radically different under different political regimes, though the degree of damage may vary. The article also contends that the majoritarian rule is more conducive to the capitalist accumulation process than to equitable growth and distributive justice. Therefore, this article attempts to prove that under neoliberal capitalism it is not only the party ideology and strength that affects the economic development but also its relationship and contradictions with the economically ruling class. 2 In order to expose the alliance between far-right political forces and neoliberal capitalist rule, it is important to analyze the economic consequences of right-wing authoritarianism and neoliberal (ir)rationality through the prism of class analysis. In this context, India is an ideal case to explore the legitimacy of the above arguments.

India officially accepted neoliberalism as a policy device in 1991. Since 1991, regardless of political regimes, all economic policies have followed neoliberal rationality, albeit that initially political parties in India hesitated to openly favor neoliberalism as a political ideology. During the political instability from 1989 to 1999, political parties could not openly embrace neoliberal ideology as a part of their manifestos. However, after 1999 the gradual movement of two leading political parties (the Indian National Congress and the Bharatiya Janta Party) toward political stability through political alliances gave way to the ascendancy of neoliberal (ir)rationality over the entire socio-economic formation. The majority of the political parties in India (both national and regional) have made efforts to reformulate their ideologies to become compatible with the rule of neoliberal capitalism. The neoliberal ideology ruling over India’s political economy for many decades entered into a new phase with the exceptional support of the ruling capitalist class to the right-wing Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) in the 2014 election and further consolidation of its hegemony in 2019. In order to meet the expectations of the capitalist class, BJP has been changing the path of India’s political economy in a manner that has further accelerated the process of primitive capitalist accumulation. 3 The fusion of BJP’s political and social agenda with the economic rule of neoliberal capitalism has put the Indian economy into a severe crisis.

In order to examine the economic consequences of authoritarian neoliberalism in India, the present article proceeds in three parts. The first part is prefaced by the conceptualization of authoritarian neoliberalism, followed by its specificity in the Indian context. The second part examines the economic consequences of the new form of political-economic rule. This section provides sufficient empirical evidence to expose the outcomes of the authoritarian neoliberal rule on economic development and employment. The third part exposes the class character of widespread austerity measures and authoritarian shocks and their consequences that have played a decisive role to expand the network of primitive capitalist accumulation.

Rise of Authoritarian Neoliberalism in India

A brief scrutiny of neoliberal thought and practice will allow us to better grasp the rise of authoritarian neoliberalism in India. The neoliberal theory produced in the Global North by right-wing intellectuals (Friedman, Hayek and Carl Schmitt) 4 differs from neoliberal practices in the Global South. Neoliberalism during the 1970s gained prominence as a strategic political response to the declining profitability of mass production industries and the crisis of Keynesian welfarism in North America and Western Europe. Following the debt crisis of the early 1980s in the Global South, neoliberalism emerged as a joint project of multilateral international institutions and the USA to suggest/enforce restructuring policies for the economies of the Global South in a manner to bring them out of structural and balance of payment crisis through integration with the world capitalist system. Thus, the implementation of neoliberal policies in the Global South has defined the developmental strategy in terms of opening their economies to international capital and integrating their petty production sector into the networks of global capitalist accumulation. The neoliberal project in the Global South was least interested in transforming the existing political regimes of developing countries into democratic ones. The disinterest in Northern-centric narratives and neoliberalism in many countries of the Global South is well evident from the fact that during the 1970s, in many countries of Southern America (Brazil and Uruguay), neoliberalism proliferated in authoritarian political regimes (Connell and Dados 2014). Neoliberalism in the Global South had been installed by the state through violence, corruption, and deregulation. This has led to, what Mbembe (2001) called, “indirect private government” or the blurring of public and private sectors to benefit the national and transnational corporate and financial elites. Thus, neoliberalism in the Global South has evolved as a new organizational form of economy and politics that has created opportunities for those who are anti-leftist and anti-welfarist statism.

To understand the evolution of authoritarian neoliberalism in the Global South, the insights from Hall’s (1979) account of Britain’s political economy in the 1980s are useful. He defined “authoritarian populism” as a particular type of conservative politics. He argues that, unlike classical fascism, it retains most (though not all) of the formal representative institutions in place. However, at the same time, it entails a striking weakening of democratic form and initiative, but may not necessarily be their suspension. He characterized it as construction in part by depicting specific groups as an ominous enemy within. As Nilsen (2018) argued, these enemies are typically political dissidents and minority groups. They are the target of repression and punitive discipline in the name of national interest. In this process, authoritarian right-wing forces tighten their grip on society and the body politic, to the detriment, obviously, of democratic life. Hence, authoritarian neoliberalism should be understood as a combined project of a right-wing majoritarian repressive regime and uncontrolled progress of the neoliberal project of accumulation through mass dispossession and displacement in favor of corporate and financial elites. In addition to the characteristics of a neoliberal democratic regime, the main elements of the contemporary authoritarian neoliberal regime include traditional morals (orthodox values), concentrated political power, race/religious norms, marginalization of economic questions, the popularity of antidemocratic means, biased mainstream media, and centrality of pseudo nationalism and militarism. The contemporary authoritarian statism in different parts of the world is an outcome of the capitalist crisis and the failure of the neoliberal democratic state to meet the expectations of the ruling capitalist class (Poulantzas [1978] 2014; Bruff 2014; Oberndorfer 2015). It is a new form of rule to impose austerity through states reconfiguring themselves in an increasingly non-democratic way in response to the crisis of neoliberal hegemony (Albo and Fanelli 2014). The power of authoritarian statism to control and divert the mass consciousness about economic injustice through ideological and repressive state apparatuses played a determinant role in earning the support of the capitalist class steeped in crisis after the global financial system meltdown in 2008. 5

The far-right authoritarian nationalist leaders are vowing to confront not neoliberal capitalism but a particular type of political bodies (such as leftist, secular, and democratic ones). This communal form of neoliberalism has been justified by the unwieldy combinations of nationalist values and the imperatives of further austerity (Boffo, Saad-Filho, and Fine 2018). As per the neoliberal (ir)rationality, right-wing authoritarian racist and communal political bodies can ensure three things for the economic elites: (i) manage markets as per the requirements of the ruling capitalist class; (ii) substitute economic questions with non-economic issues/concerns in order to present economic injustice inferior to the questions of the nation, race, caste, gender, etc.; (iii) mold the economic and political role of the state in the name of individual sovereignty, governance and corruption as per the requirements of capitalist rule.

The rise of the authoritarian neoliberal regime in India is an outcome of the failure of neoliberal democratic regime to meet the expectations of the working majority. Originally, liberal (secular) democracy in India was an outcome of the balance between economic and political power. However, since the 1980s, the advent of neoliberalism in India has disrupted the balance between economic and political power. The incompatibility of neoliberal rationality and democratic principles has now fully been uncovered in India. Neoliberal ideology has openly brought the state (politics) to the service of economic elites and tuned its role as per their requirement. The emergence of neoliberal capitalism in India has made efforts to depoliticize economic fields through the removal of regulations and control of the free movement of capital. The principles of equality, popular sovereignty, inalienable rights, etc., as Vazquez-Arroyo (2008) argued, have been reduced to the political sphere only and under the shadow of this economic equality, freedom, economic sovereignty, economic rights, etc., have been effectively diluted.

In 1991, Indian political leadership and mainstream political parties officially accepted the neoliberal principles and compromised the social content of democracy as per the guidelines of the institutions of neoliberal ideology (World Bank, IMF and WTO), who in return provided an immediate solution to the ongoing fiscal and balance of payment crisis (Singh 2021). The first phase of neoliberalism (1989 to 1999) in India gave birth to political instability. From 1989 to 1999, no single party ruled for a complete term (five years). In fact, seven prime ministers have shared the office in these tumultuous ten years. Then in 1999, BJP (right-wing communal-nationalist party) succeeded to form a coalition government and it was the first time in India’s history that a non-Congress and, more importantly, the communal-nationalist party ruled over the Indian political system for five years. The two major national political parties, Indian National Congress (Congress) and BJP, successfully adjusted their ideology with neoliberal capitalism in the second phase of neoliberalism that started from 1999 onwards. A careful study of their manifestos reveals that there was no radical difference in their economic policies. However, the economic policies of the BJP were and continue to be more radical to tune India’s economy with the accumulation logic of neoliberal capitalism. With the support of neoliberal forces, Congress was able to come back into power in 2004. Its commitment to fulfilling the interests of neoliberal capital paved the way for increased economic growth. However, the widespread austerity measures worsened distributive justice. The period from 2004 to 2014 marked the complete transition of the Indian political system into a neoliberal democracy. During this period, neoliberal policies successfully replaced the rule of the political constitution with the rule of the economic constitution. 6

Eventually, the alliance between the Congress party and the capitalist class was called into question due to the massive inequality affecting different segments of the population, joblessness, widespread dispossession, deterioration in living conditions, marketization of social services (education and health), etc. In addition, the weak position of Congress due to its alliance with many political parties (including the parliamentarian left), rendered it incapable to meet the expectations of even the capitalist class. This dissatisfaction of the people with the performance of neoliberal capitalism and the Congress-led UPA (Union Progressive Alliance) had been effectively channelized by the right-wing BJP, not against neoliberal capitalism but against Congress. Further, the politicization of popular mass struggles (Anna Hazare movement, for instance) by the right-wing communal-nationalist forces also channelized these movements that should have been against neoliberal capitalism toward a particular political party (Congress).

The present-day right-wing authoritarianism in India is not a counter-movement against neoliberal policies introduced by the UPA, but rather a mouthpiece of neoliberal capitalism. It is a consequence of Congress’s failure to maintain a secular political base, parliamentary socialist ideology and support of the capitalist class. The economic program of Congress has become more and more indistinguishable from BJP. BJP’s ideology differs from Congress not because it favors economic neoliberalism but because it also favors national conservatism and right-wing communal-nationalism. The economic crisis and policy paralysis in India that was the outcome of the financial crisis at a global scale and failure of the weak UPA government to meet the expectations of the capitalist class can be considered the beginning of reconfiguring of the Indian state. The reconfiguring of the state on authoritarian lines was promised by the majoritarian BJP in the NDA (National Democratic Alliance) government to provide institutional support to neoliberal capitalism to come out of crisis, on the one hand, and divert the mass attention away from its failure to deliver anything concrete to common masses through religious, caste, and ethnic politics, on the other hand. Something qualitatively distinct has been created to cloak the authoritarian essence of the BJP. This is quite similar to the ordoliberal system that Havertz (2019) articulated, in which the state obtains the authority mainly through a promise of preserving the institution of the free market by the establishment of a political order that reaches deeply into society as per the requirements of the neoliberal capitalist class. The BJP is ingraining the agenda of Hindutva deep into the minds of the people in order to ensure free space for neoliberal economic forces to shape the economy as per their requirements. The ruling BJP is trying to establish a regime of truth, as Foucault (1991) pointed out, by producing a new form of knowledge, inventing new notions and changing the existing notions and concepts that can intensify the government of new domains of regulations and intervention in economic, social, and political life (Lemke 2002). Hence, the rise of the right-wing BJP can be understood as an outcome, as Nilsen (2018) said, of the failure of the inclusive neoliberalism agenda of the Congress-led UPA government that became evident in the second term of the UPA in the form of uneven implementation of welfare schemes, scams, corruption, and policy paralysis. Moreover, as Chacko (2018) argued, the greater liberalization of the economy and increased reliance on imported resources left India’s economy more vulnerable to global shocks, such as the global financial crisis, higher oil prices and falling global demand. The failure of the UPA-II agenda of inclusive neoliberalism to mitigate the effects of dispossession, displacement and immiseration generated the charges of policy paralysis and corruption by the BJP under Modi’s leadership, becoming the central plank of its successful election campaign (Sinha 2017a). Along with focusing on the inability of the Congress-led UPA-II to complete the transition of the Indian economy to mature capitalism, Modi lampooned previous attempts at poverty elimination and social deprivation. The main target of BJP’s right-wing populist propaganda during elections was the Congress party, which was defamed as the party of the Gandhi family (political elite). Along with them, BJP also targeted minorities, especially Muslims, Christians, and Bangladeshi immigrants who were alienated as “others.” The propaganda was also launched against communists and intellectuals who were branded as anti-national elements. To further distract the electorate away from the economic failures, the BJP dragged Pakistan and China into the electoral rhetoric, labeling them as architects of an international conspiracy against India’s geopolitical sovereignty.

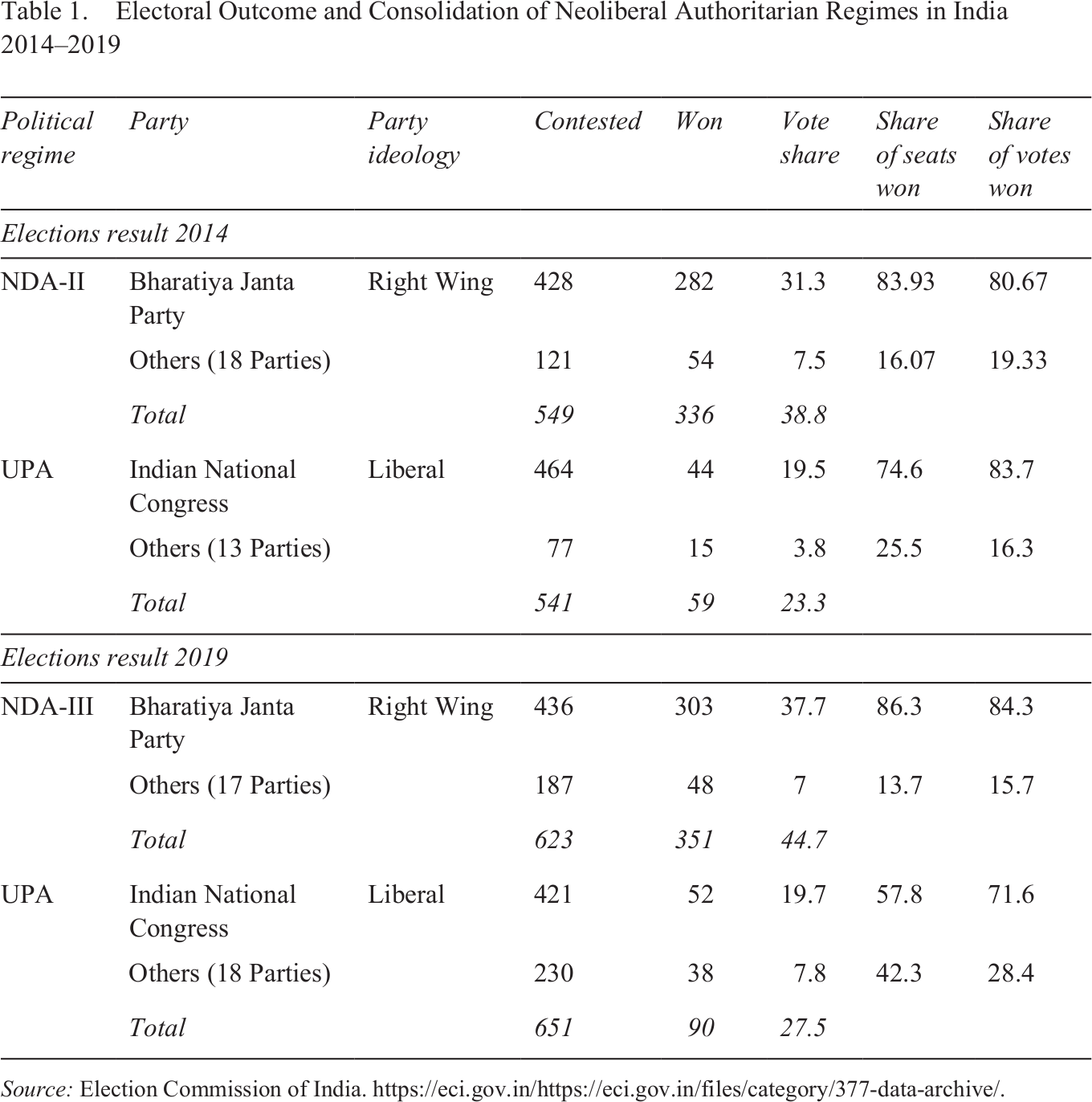

The political consolidation of authoritarian neoliberalism in India can also be examined through the rising popular electoral support for the right-wing BJP. Modi received unreserved support from all fractions of Indian and transnational capital, from the neo-middle class, from the youth and the rich peasantry. Moreover, his support cut across class and caste, breaking and drawing fragments that were previously consolidated into other units of political mobilization. The victory of the BJP-led NDA-II in 2014 was a major turning point in India’s political history. The last time that a political party had secured such a massive majority in the Indian parliament was in 1984 when the Congress party swept the polls on sympatharian grounds after the death of Indira Gandhi (Ahmad 2015). Moreover, it was the first time in independent India’s political history that the right-wing BJP had secured a majority that cut across caste and class along with the exceptional help of corporate and financial elites to form a majoritarian government. Even though after 2014, the BJP miserably failed on the economic front to deliver anything concrete to the common masses, it has once again successfully formed a strong government with 303 independent seats out of 351 seats of the NDA of a total of 18 parties in 2019. This was achieved through populist slogans and polarization of the Hindu votes using rhetorical tropes: religion, caste, ethnicity, national security, and Hindu nationalism. Thus, Modi successfully displaced economic issues with non-economic communal and conservative nationalism. Nationalism and national security have been effectively used as an instrument to appeal to the common masses. Added to this is the corporate media-created image of Modi as a “strong leader” who has risen from poverty, represents the poor and at the same time is capable to use force to curtail anti-national activities by the people within the country and threat to political sovereignty posed by neighboring countries. In this way, the collective strength to counter the real forces of pauperization has been replaced by the personal strength to create social harmony through majoritarian ethnicity. The absolute majority of the BJP and the unchallenged authority of Modi within the party has brought him closer to the super-rich segment of the capitalist class which has heavily sponsored him to take command of political power. 7

Electoral Outcome and Consolidation of Neoliberal Authoritarian Regimes in India 2014–2019

Source: Election Commission of India. https://eci.gov.in/https://eci.gov.in/files/category/377-data-archive/.

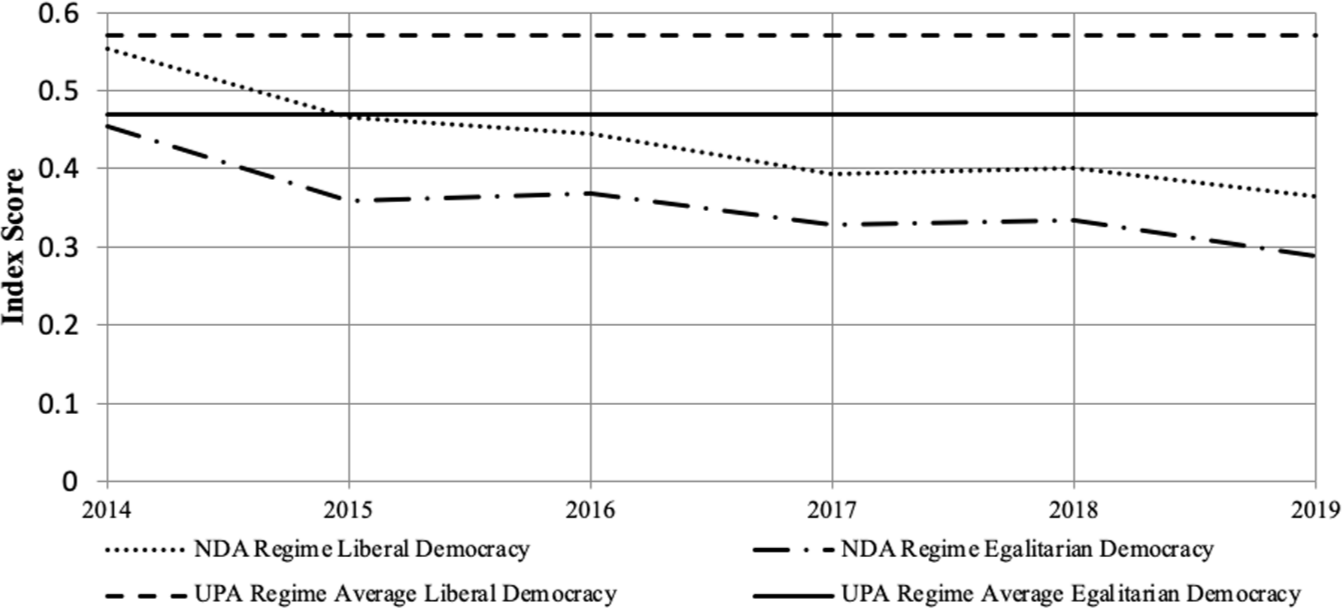

Since 2014, the analysis of the character of the right-wing part of governance led by Modi shows that it is, what Fraenkel ([1941] 2006) called, the “dual state” (the coexistence of a prerogative state and a normative state). The prerogative characters of the contemporary state refer to exceptional and extraordinary political power unchallenged by parliament and institutional structure. The normative character refers to the administrative body managing the economy as per the interests of the capitalist class. The prerogative character of the Modi-led BJP government revolves around hyper-nationalism, religious, and ethnic hegemony, a violent cleaving of society into two groups—a pure people and enemies of the people and the need for state and state-sanctioned repression of dissent and opposition on the one hand, and on the other, a neoliberal restoration with growth rates, credit rating, foreign direct investment, ranking on World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) indices. This prerogative character of the Modi-led majoritarian government and its consequences on the political system is also visible in a staggering decline in liberal and egalitarian democracy in India (Figure 1). While it is conceivable that the gradual decline of the liberal democratic regime since the 1980s in general and under the neoliberal democratic regime since 2004 in particular, has set the foundations of the neoliberal authoritarian regime in India, the liberal and egalitarian index under contemporary authoritarian regime has recorded a sharp decline from the average of both forms of democracies under the UPA-led neoliberal regime (2004–2014).

Liberal and Egalitarian Democracy Index under Authoritarian Neoliberal Regime

Source: Varieties of Democracy. https://www.v-dem.net/en/.

A robust civil society, a well-respected judicial system, constitutionalism, rule of law, and relatively free media are losing ground under the prerogative state. The policy debates in the media and elsewhere, which were centered around economic development during the UPA regime, have been replaced by religion, ethnicity, military, and China and Pakistan’s conspiracy to hurt India’s international image. Under the shadow of a racial conception of Hindutva, the usable state bureaucracy that operates with professional norms has been used to integrate all the spheres of India’s economy with the accumulation logic of neoliberal capitalism. For such a polity to be successful, the only necessary condition is undermining the democratization process in various spheres of life, that is, sabotaging the autonomy, freedom, collective power, and legitimacy of democratic institutions.

In the contemporary era of authoritarian neoliberalism, as Foucault (2004) argued, it is not the state that regulates and controls the economy. It is the economy that has state-creating and state-legitimizing functions. The alliance between the BJP, extra-paramilitary organizations like Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and national and transnational elites is an ideal specimen to understand Foucault’s governmentality that refers to the involvement of co-opt actors (outside the institutional framework of government) in government rule. The neoliberal governmentality of Foucault is not about the retreat of the state but rather the prolongation of government. In other words, neoliberalism is not an end but a transformation of politics that restructures power relations. The expansion of neoliberal (ir)rationality under an authoritarian political regime represents the new relationship between neoliberal rationality and what Foucault said technologies of the government. The systematic restructuring of the technologies of the government (mode of regulations, fields of action, and power relations) as per neoliberal ir(rationality) and Hindu nationalist agenda of RSS is blurring the boundaries between government, the capitalist class and RSS.

Economic Consequences of Authoritarian Neoliberalism

Since 1991, neoliberal rationality has unfolded in India as a pro-capitalist model, not a pro-market one. The latter, in principle, refer to decentralized market support for democracy, efficient use of factors of production, labor-intensive industrialization for rapid employment growth, shifting of the term of trade in favor of the countryside, benefiting the rural poor, mitigating inequalities, etc. On the other hand, the pro-capitalist model is accompanied by growing capital intensity, the retreat of the state from production and distributional spheres, growing inequalities, growing concentration of ownership of private industries, deterioration of employment conditions, and a fall in the wage share. The pro-capitalist model of India rests on a fairly narrow alliance of the political and economic elites (Kohli 2006; Jaffrelot, Kohli, and Murali 2019). The class character of the current political regime is that the right-wing BJP has not brought any major change in the mode of production. As Fraenkel’s conception of a “dual state,” the normative character of the Indian state is visible in the form of the BJP’s economic policy to radicalize the neoliberal project. Hence, despite its anti-Congress position, the BJP does not want to break from the neoliberal economic agenda but rather wants to radicalize it. The contemporary authoritarian neoliberal rule in India has redefined, what Block (1987) said, the general interests of capital as interests of a particular segment (super-rich) of the capitalist class. To meet the interests of the big capitalist class (such as Adani and Ambani), the Modi-led BJP is formulating/redefining policies against the interests of small businesses, petty producers, and the working majority. The RSS, which ideologically rules over the BJP’s economic, political, and social policies, traditionally supported protectionist economic agenda and has supported Modi’s ultra-liberal Gujrat model as a national strategy. Mukhopadhyay (2016) argued that this shift in the economic ideology of RSS was an outcome of Modi-Shah’s convincing strategy that while this strategy may erode the supporter base of small traders, small businesses, and farmers, but simultaneously new supporters would emerge among the poor and new middle classes as they have in case of Gujrat. Hence, the economic downturn of India, which started due to external shock in the form of the global financial crisis of 2008, has become internal due to the exclusion of interests of the majority of small businesses and petty producers in the economic policies of the BJP. The economic consequences of the unchallenged alliance between the majoritarian BJP, the super-rich capitalist class and the RSS are well reflected in the macroeconomic performance of the Indian economy.

During the UPA-I regime (2004–2009), the gross value addition (GVA) growth rate was around 8%. However, due to the global financial crisis in 2008, the growth rate of GVA declined. If we exclude the outlier years of 2008–2009 and 2009–2010, then the average GVA and per capita income growth during the Congress-led democratic neoliberal regime was 7 and 6.3%, respectively (RBI [Reserve Bank of India] 2020). When the NDA came into power in 2014, as Das (2020) argued, it enjoyed three advantages: a recovering global economy from the financial crisis of 2008, falling oil prices due to which the government received a bonanza of Rs. 6 lakh crores in revenue and an absolute majority of BJP in the parliament. Despite these advantages, the economic performance during the BJP-led NDA rule remained lackluster. The sectoral growth of GVA among the major sectors during the NDA regime remained lower than the UPA average growth rate except in community, social, and personal services (Table 2). The overall GVA and per capita income growth under the NDA regime (2014–2015 to 2019–2020) were 6.7 and 5.5% respectively, well below the average of the UPA regime. 8

Annual Growth Rates of Real Gross Value Addition at Factor Cost by Industry of Origin (%)

Notes: Agriculture also includes forestry and fishing, mining, and quarrying; manufacturing also includes construction, electricity, gas, and water supply; trade and hotels also include transport and communication; financing and insurance also include real estate and business services. The values from 2017–2018 onwards are revised estimates of GDP.

Source: RBI (2020) and GOI (2020).

The decline in growth rate under the NDA regime was higher than forecasted. After leaving office, former chief economic advisor of the NDA-I government, Arvind Subramanian (2019), confided that the real GVA growth in India was about 2 to 2.5% less than the official estimates of GVA growth from 2011–2012 and 2016–2017. Now one can well imagine the real GVA growth when official figures stated it to be 3.9% in 2019–2020. There is hardly any important industry that has recorded a decent growth rate under the current political regime. In comparison to its average growth rate under the UPA regime (7.5%), the average growth rate of the manufacturing sector was recorded at 6.1% under the NDA. Recent data reveals that it declined to only 0.7% in 2019–2020. Many important industries—such as automobile, paper production, coal and petroleum, rubber and plastic, electronic equipment, transport equipment, and other machinery and related equipment—have been experiencing deceleration in growth. The growth rate of agriculture, which is the principal occupation in the countryside, has recorded an average growth rate of 3.3% under the NDA regime (Singh 2020). The government’s utopia of doubling farmers’ income by 2022, as Montek S. Ahluwalia (2019) revealed, requires 12–14% growth.

The question arises: Why is there a deceleration of economic growth under the current political regime? It can be inferred from the above analysis that when political power is not monopolized by one political party, as in the case of the UPA-I and UPA-II, the pressure to deliver in economic terms is higher. The left political parties, along with other regional political parties of center-left ideology which were part of the UPA, had played an important part in the decision-making process of ruling Congress at that time. They kept the possibility of ultra-liberal policies giving excessive benefits to the big capitalist class by Congress in check. Under weak political rule, the neoliberal capitalist class, which requires a stable political system, was also bound to deliver in terms of economic growth. However, the majoritarian BJP led by the absolutist character of Modi ensured the command of national and transnational corporate and financial elites over the economy and extended the base of primitive capitalist accumulation through centralization of the economic activities to a few hands. Another inference from the above analysis is that, unlike the mainstream notion, majoritarian rule in India has made the Modi-led BJP relatively independent of the parliament as well as institutional constraints, allowing them to promote the interests of a few fractions of Indian and transnational elites.

If we leave political factors aside and focus solely on economic causes, then the well-known mainstream growth theories (Harrod 1939; Domar 1946; Solow 1956) state that the rate of economic growth and employment (at a given capital-output ratio) is mainly determined by the rate of savings/investment. The higher GVA growth in the democratic neoliberal regime (2004–2014) was an outcome of a historically high level of savings and gross capital formation. However, under the authoritarian neoliberal regime (2014 onwards), both have secularly declined in comparison to the average of the UPA-I and UPA-II (Figure 2).

Household savings, which constitute a substantial proportion of national savings and investment, have declined from 23.6% in 2011–2012 to 17.2% in 2017–2018. The decline in household saving and capital formation rate under the current regime is the outcome of the introduction of widespread mass income deflationary policies with an objective to consolidate the rule of the capitalist class over the production systems. The increased stress on the household sector due to the continuity of austerity measures and pro-capitalist class economic policies during the years of mass economic distress has undermined the capacity of the household sector to save a higher fraction of their earned income.

As per mainstream growth theories, the reduction in savings and gross capital formation under the current authoritarian neoliberal regime has diluted the steady-state growth path. The weak Congress-led governments (due to political compulsion) had tried to attain this growth path by reducing the gap between GDP and employment growth during 2004–2014. However, the economic stress-led decline in the saving/investment rate under the contemporary authoritarian neoliberal regime has produced widespread involuntary unemployment.

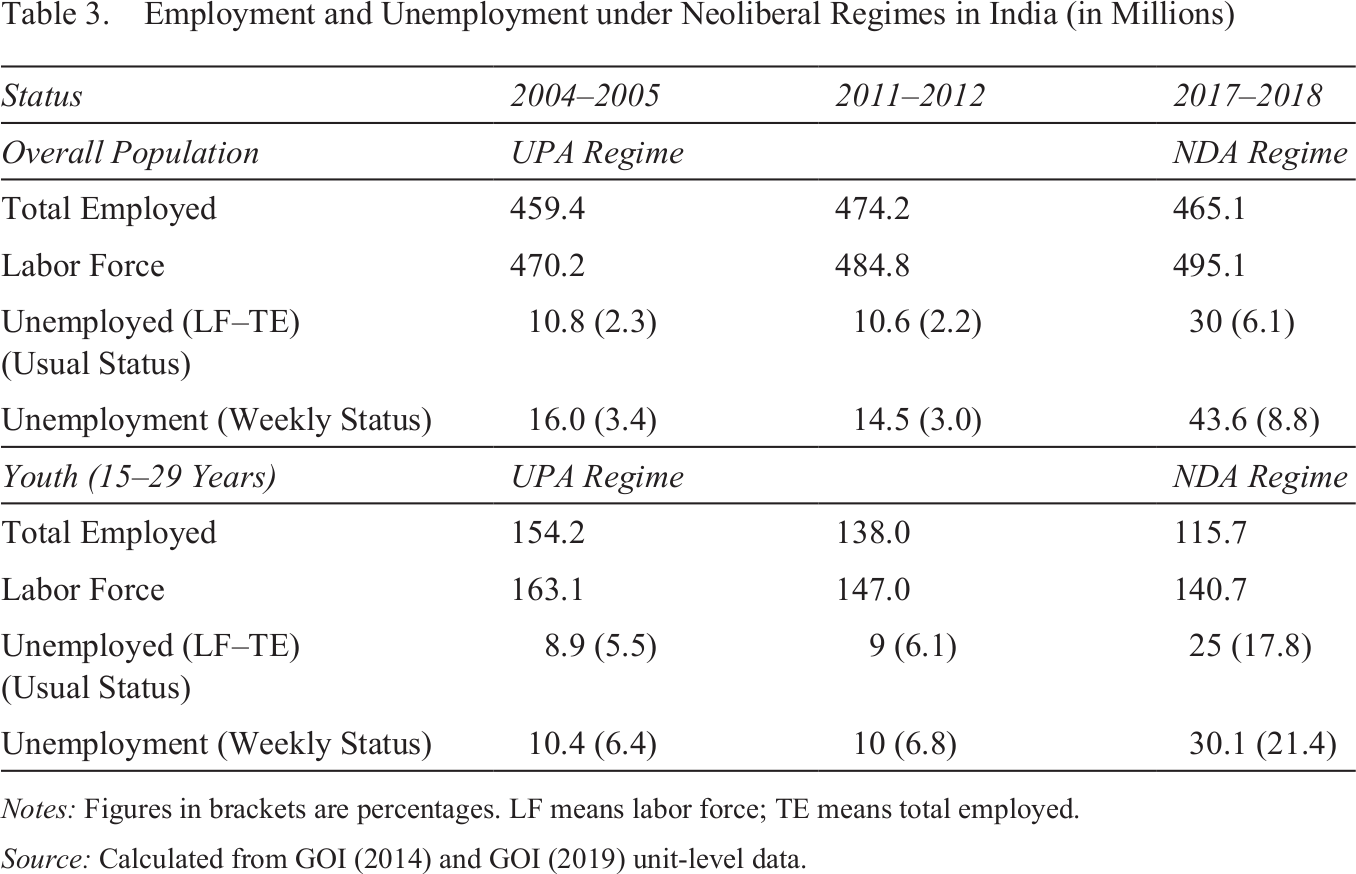

An elementary calculation of unemployment based on the recent Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data highlights that in 2011–2012 the total workforce in India was 484.8 million, out of which 474.2 million were employed. In 2017–2018, the labor force increased to 495.1 million, whereas employment declined by 10 million from 2011–2012 (GOI 2019). There are various ways to examine the incidence of unemployment. If we use the most common measure of “usual status” unemployment, then, during the UPA regime (2004–2005 and 2011–2012), the unemployment rate was 2.3% (GOI 2014). Usual status unemployment is an indicator of “chronic unemployment,” that uses a reference period of 365 days. This measurement estimates the number of persons who belong to the labor force but remained unemployed for more than half of the period. The National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) had not conducted a survey of employment and unemployment since 2014, when the NDA came into power. So, we use 2011–2012 data on chronic unemployment as a proxy for 2014, in which 10.6 million, based on usual status, were unemployed. When we compare these figures with the unemployment figures of 2017–2018, which stood at 30 million, the economic consequences of the neoliberal authoritarian regime on the labor market become fairly manifest. We can also look at unemployment based on “current weekly status,” according to which a person is not considered unemployed if he or she can secure at least one hour of work in the preceding seven days. According to this definition, in 2004–2005 and 2011–2012, on average,3.2% of India’s workforce was unemployed, and this percentage increased to 8.8% in 2017–2018, which means that more than 43.6 million persons were unable to find even one hour of work in a week. Despite all the manipulations forced by the authoritarian statecraft to tone down the figure of unemployment, it remained the highest in the last 45 years, since the NSSO conducted its first survey. According to PLFS data, the chronic unemployment rate was 6.1% in 2017–2018; if we calculate the absolute number, approximately 30 million workers ready and available to work at the prevailing wage rate were chronically unemployed. The picture gets darker if we decompose the unemployment rate. Youth unemployment has risen steeply under the current regime. Out of India’s total chronically unemployed (30 million) in 2017–2018, 25 million were youth unemployed (15–29 years), and out of 43.6 million unemployed on current weekly status, 30.1 million were youth. To add, in 2017–2018, on average 35% of the youth with graduation (and above), technical, or vocational education was unemployed in India.

But why has the unemployment rate increased so sharply under the current majoritarian regime? If we examine the economic factors only, the rate of employment growth under capitalism is not only determined by the saving/investment rate but also by the difference between the rate of growth of output (which depends upon the savings and capital-output ratio) and the rate of growth of labor productivity (which depends on the pace of technological progress). An increase in the growth rate of output accompanied by a more than proportionate increase in the growth of labor productivity is an important reason for widespread unemployment under the neoliberal capitalist regime in India (Patnaik 2011). Moreover, as Kalecki (1971) pointed out, business leaders in a capitalist economy discourage government efforts to increase employment growth because it can increase the bargaining power of workers for better conditions and, therefore, reduce the profit margin. To accelerate the process of accumulation by the capitalist class, contemporary authoritarian government, instead of increasing public investment, is not only continuing but accelerating the disinvestment in the public sector. For instance, when the BJP came into power in 2014, the government received Rs. 15,819.46 crores from disinvestment in public sector units. This amount increased to around Rs. 1 lakh crores in 2018. In 2020–2021, the government hoped to gain Rs. 2.1 lakh crores through disinvestment. The widespread disinvestment, even in recessionary phases of economic activities, is a peculiar feature of the contemporary authoritarian neoliberal regime that has undermined the potential of the economy to compensate for the employment loss caused by the disproportionate shift in private capitalist investment in favor of capital augmented technology. The submission of all the remaining public sectors units to big capitalists, the motive of which is nowhere to ensure full employment equilibrium but to expand the command of the capitalist class over the economy and maximization of profits, has increased the magnitude of non-exhaustive labor reserves in India (Singh and Tiwana 2020; Singh and Kumar 2021).

Employment and Unemployment under Neoliberal Regimes in India (in Millions)

Notes: Figures in brackets are percentages. LF means labor force; TE means total employed.

Source: Calculated from GOI (2014) and GOI (2019) unit-level data.

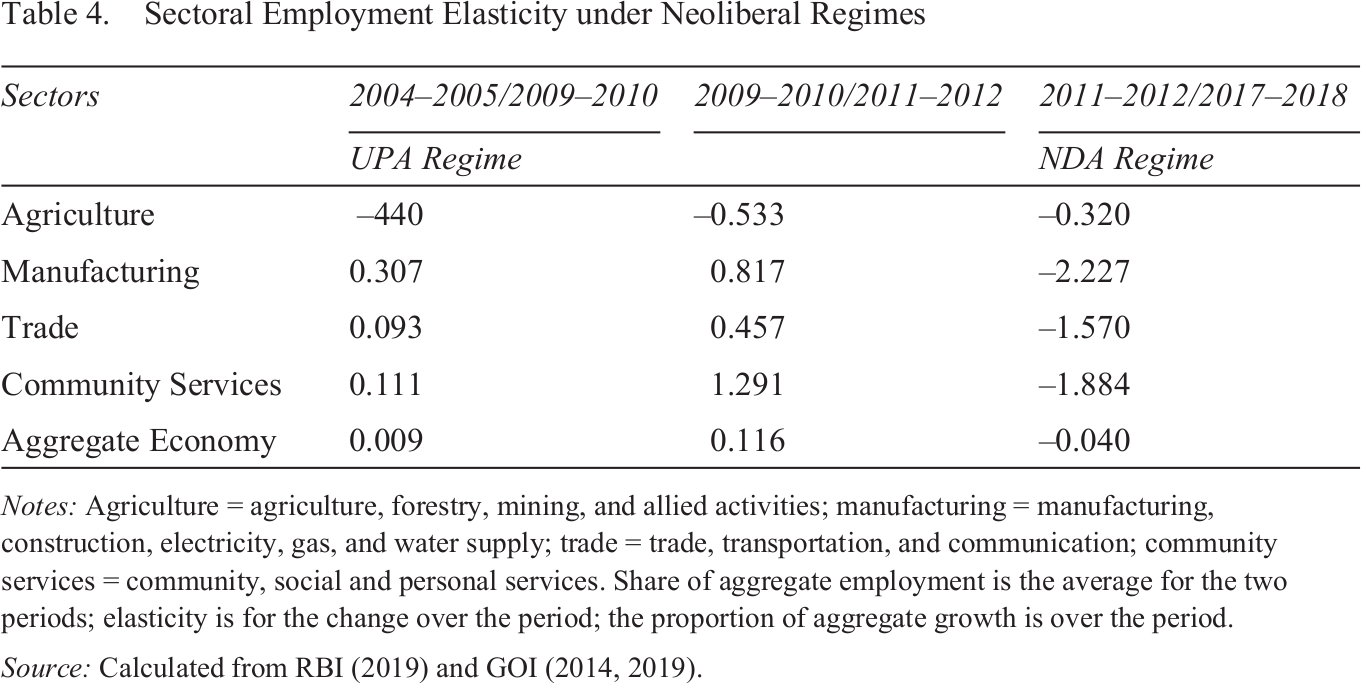

In other words, the removal of regulations and control on private capital on the one hand and the unwillingness of the government to regulate, what Harvey (2014) argued, adoption of new technological labor displacement forms of production, on the other hand, has undermined the responsiveness of GDP growth to generate enough employment opportunities in neoliberal India. Table 4 highlights that the output growth under neoliberal regimes is not a result of the increase in demand for labor but the increase in labor productivity induced by labor displacing technology. The employment elasticity of GDP was very low (but marginally positive) for all the sectors (except agriculture) under the weak UPA regime. However, the employment elasticity of GDP under a contemporary strong BJP-led regime is negative for all the sectors of the economy. This implies that, on average, 1% growth of the manufacturing sector during 2011–2012/2017–2018 displaced 2.227% of workers from employment. The Indian economy, as argued by Kannan and Raveendran (2020), has gone from jobless growth under the neoliberal capitalist regime led by Congress to job-loss growth under the contemporary regime.

Sectoral Employment Elasticity under Neoliberal Regimes

Notes: Agriculture = agriculture, forestry, mining, and allied activities; manufacturing = manufacturing, construction, electricity, gas, and water supply; trade = trade, transportation, and communication; community services = community, social and personal services. Share of aggregate employment is the average for the two periods; elasticity is for the change over the period; the proportion of aggregate growth is over the period.

Source: Calculated from RBI (2019) and GOI (2014, 2019).

The right-wing authoritarian and neoliberal alliance occurred when precarious employment was spreading in India, a development long underway since the introduction of neoliberalism in the 1990s and intensified after the global financial crisis of 2008. It presents many important aspects of the Indian labor market under neoliberal capitalism. The intensive use of authoritarian statist measures to introduce pro-capitalist economic policies aimed at formalizing the primitive accumulation process requires the widespread informalization of labor market. During neoliberal regimes in general, and contemporary authoritarian regimes in particular, the old forms of labor are being transformed and made conducive to the accumulation process. Formal employment activities which are considered decent due to job security, provident funds, medical insurance, etc., are on the decline. On the other hand, the proportion of workers working under the threat of multiple insecurities in informal activities is increasing (Tiwana and Singh 2015). Existing on a continuum, conditions of precariousness have also become increasingly normalized in formal sites of employment in India. The increasing informalization, casualization, and dispossession under the neoliberal regime are outcomes of, as Sanyal (2007) argued, primitive-type accumulation. It is primitive in nature because the process of capitalist transition in India is neither complete nor ever likely to be so in future. Capitalism in India is in a constant state of becoming, never reaching the stage of being. The persistence/mounting of degraded labor, unorganized labor, and unclarified labor process is significant for primitive-type accumulation, capital’s logic and social separations or divisions (of work and property, labor and wealth, producer and the product, etc.) (Samadhhar 2009).

The evolution of the authoritarian neoliberal regime in India took place to preserve/accelerate the process of primitive capitalist accumulation. In this process, neoliberal statecraft has produced/facilitated the conditions of dispossession and expropriation. The unorganized labor, which is an important condition of the accumulation process under capitalism, stands free in the double sense Marx speaks of—dispossessed, free from attachments, and free as a juridical person to accept any conditions offered to him/her (Samadhhar 2009). It is evident that due to the continuous decline in the bargaining power of trade unions and the introduction of widespread austerity measures by the neoliberal governments, full-time permanent work in both private and public sectors has increasingly been informalized (Thomas 2020). Under the UPA-I regime (during 2004–2005), out of the total workers employed in the non-farm sector, 136.7 million were employed in the unorganized sector, which increased to 181.1 million in 2017–2018. In 2004–2005, informally employed workers in the non-farm sector were 162.4 million, which increased to 217 million in 2017–2018. The incapability of the formal and organized sector to absorb the incremental workforce in the labor market, on the one hand, and efforts for formalization of the exploitation process by the authoritarian neoliberal regime, on the other hand, has increased uncertainties and insecurities even at formal sites of work. The anti-employment and anti-poor attitudes are also visible in other policies of the authoritarian neoliberal regime in India. To reduce the pace of dispossession and displacement caused by the primitive accumulation process in rural India, the Congress-led UPA (under the pressure of left and center-left parties) introduced Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in 2006. The objective of MGNREGA was to provide 100 days of unskilled manual employment to one member of a poor rural household. This initiative to reduce the effect of neoliberal capitalist encroachment has been derailed by the current authoritarian regime. The funding of MGNREGA as a percentage of GDP has steadily declined from 0.53% in 2010–2011 to 0.42% in 2017–2018. The recent budget allocation of 2021–2022 to MGNREGA has declined by 34% of the total estimated expenditure for 2020–2021 (Ministry of Finance 2021). The delay, as well as the decline in funding for rural employment programs, is an important component of the current political regime to expand the scope of primitive accumulation by neoliberal capitalism. The government’s facilitation of the encroachment of the production system of petty producers of the countryside by the capitalist class is a part of the conscious effort to accelerate the process of dispossession and displacement in India. As Sanyal (2007) argued, in postcolonial India, unemployment and underemployment are a permanent and internal part of the process of development itself. The Indian labor market under the current regime is wrought with informalization, insecurity, underemployment, and unemployment made worse by the increased pace of capitalist accumulation. The Modi government is using state power to increase the reserve pool of labor through land acquisitions to hand over it to the national and transnational capitalist class and is dismantling labor laws in the name of reforms to enhance the process of dispossession and displacement.

Consequences of Neoliberal Austerity and Authoritarian Shocks

Another aspect of the neoliberal political regime in India since 1991 is the introduction of mass income deflationary policies, or what Keynes (1971a) called “profit inflation” (a term coined by Keynes in 1930 and used extensively in his later writings to describe the financing of wartime expenditure by reducing mass consumption), which have undermined the pursuit of distributive justice. 9 In its essence, neoliberalism in India was not a project of economic growth but a redistribution of means of production and wealth in favor of corporate and financial elites. The neoliberal (ir)rationality is well evident in the important macroeconomic policy changes introduced by the Modi-led BJP government. The centralization of economic policies and their authoritarian implementation has directed the benefits of these policies to particular groups (super-rich corporate and financial elites) at the expense of the majority. It is important to expose the class aspects of macroeconomic policies and austerity measures to understand the relationship between authoritarian statism and economic elites. In this part, we examine the distributional aspects of the BJP’s macroeconomic policies (such as the low fiscal deficit, demonetization and Goods and Services Tax (GST)).

After the introduction of neoliberalism in India, the pro-cyclical fiscal measures, which involve the retreat of the state not in general but from particular spheres (such as long-term expenditure on public goods like education and public health) along with simultaneous intensive activeness in other spheres (removal of barriers for capital accumulation through the use of ideological and repressive state apparatuses) have become more frequent. The capital-centric shrunken welfare state in India has given way to a new politics of austerity that refers to a fall in public investment and popularization of market-led distribution conducive to the interests of the capitalist class. This is well evident in the policies undertaken when the BJP came into power in 2014 and when, incidentally, the Indian economy had entered the phase of low-level economic growth. Experience shows that in such a situation an increase in government investment and aggregate demand through fiscal deficit can act as a counter-cyclical measure to bring the economy back on track. But the IMF and World Bank-driven fiscal regimes that India follows do not allow any long-term increase in government expenditure. The temporary transfers, an important means of BJP’s populism to secure the votes, could not bring the economy out of a cyclical crisis. Moreover, such expenditures are neither development oriented nor fiscally sustainable. The government expenditure-driven fiscal deficit that is an important stabilizer of the economy during the low-growth regime has remained substantially low and continues to fall under the low-growth phase of the authoritarian neoliberal regime—well below the average of the UPA regime (Figure 3).

This demonstrates the pro-neoliberal character of the contemporary, so-called, nationalist government that follows profit-led and export-led strategy (beneficial for national and transnational corporates) and is determined to maintain the fiscal deficit at around 3%. Another peculiar characteristic of pro-cyclical measures of contemporary authoritarian statism is that, in order to curtail fiscal deficit, instead of reducing the government consumption and administrative and defense expenditure (because these are essential elements of its politics), it imposes austerity measures through a reduction in public investment on social sector and welfare programs (in particular on education, health, research and development, old age benefits, food subsidy, unemployment benefits, employment programs, employees benefit, etc.).

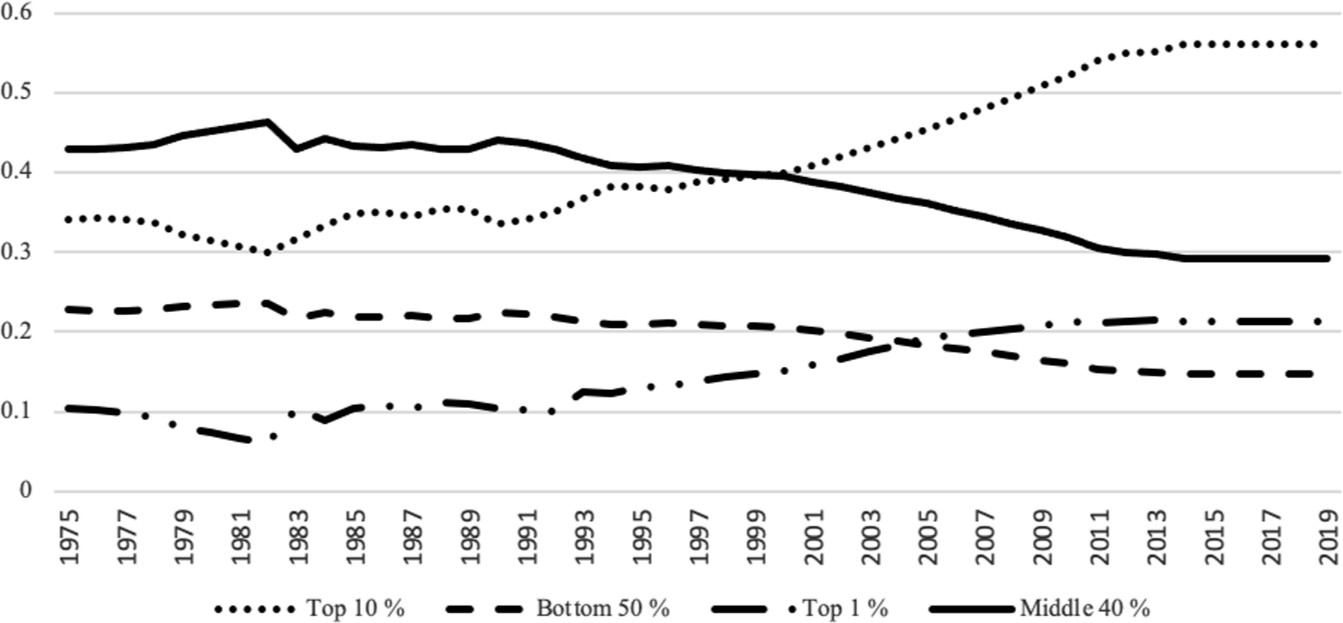

The income deflationary policies, which are an outcome of government efforts to promote profit-led and export-led development strategies to benefit the national and transnational corporations, have reduced the wage share in total income and further undermined the distributive justice pursuits for the working poor. The consequences of pro-cyclical fiscal consolidation measures and profit-led development strategy are visible in the form of widened income inequality. Figure 4 indicates the concentration of income in the hands of fractions of the capitalist class who are directly connected with global capitalism-industrial and financial elites. The share of top income groups (top 1% and top 10%) has increased substantially after the introduction of neoliberal reforms. It highlights that the issue of distributive injustice becomes clearer if we look into the wealth concentration in India. According to the “Global Wealth Report” issued by Credit Suisse (2018), the richest 1% of Indians own 51.5% and the bottom 60% own 4.7% of the country’s wealth. When the BJP came into power in 2014, the net worth of the top 100 richest Indians, as per Forbes list, was 20.77% of India’s total GDP, which increased to 25.41% of GDP in 2020 (Forbes 2022). In other words, in a nation of more than 1.2 billion population, the top 100 richest people own assets equivalent to one-fourth of the country’s GDP. If we look into the curious case of individual growth among corporates, Mukesh Ambani’s wealth has increased from Rs. 1.68 lakh crores to Rs. 3.65 lakh crores (188%) between 2014 and 2019. In Gautam Adani’s case, the wealth zoomed up by 121% from Rs. 50.4 thousand crores in 2014 to Rs. 101 lakh crores in 2019 (Verma 2019). At the same time, 80 to 90% of India’s population has experienced little increase in real income.

Income Inequality in India, 1975–2019

Source: World Inequality Database. https://wid.world/country/india/.

A spectacular increase in the income share of top income groups, which include the domestic and global capitalist class, domestic politicians, and bureaucrats, has worsened income distribution in India. These inequalities, which are an outcome of neoliberal capitalism have become even more alarming under the right-wing authoritarian neoliberal regime. Due to the increase in, what Kalecki ([1965] 2009) called, the “degree of monopoly,” by the government’s efforts of formalization of primitive accumulation by providing substantial benefits to big corporations on the one hand and ruining small businesses and petty production activities on the other hand, the wage share in total output among all the major sectors of the economy has declined substantially. The PLFS data shows that in 2017–2018 the real wages for regular workers in urban areas declined by 1.7% per annum and in rural areas by 0.3% per annum from the 2011–2012 levels (GOI 2019). From 2007 to 2013, as Kundu (2019) stated, the average growth of rural wages (both nominal agricultural and non-agricultural) stood at around 16%, surpassing rural inflation which averaged 10%. However, rural wage rate growth under the BJP-led NDA regime has been less than 3%. The deceleration began after November 2014. If we try to calculate real wages by incorporating the inflation rate, then, for most of the time, wage growth was either near zero or in the negative territory.

The neoliberal project of the contemporary authoritarian regime contains the commitment to carry out structural reforms which are conducive to restructuring and disciplining the economy as per the requirements of the capitalist class. To meet the objectives of reconfiguration of political and economic systems, the grand alliance (right-wing authoritarian and big bourgeoisie) has agreed to vacate one sphere each. The economy is assumed by the economic elites and politics by the right-wing authoritarian forces. Both these forces have also agreed to facilitate each other in their respective spheres. The multiple populist promises on the basis of which the BJP came into power were heavily popularized by the corporate-led media. 10 To fulfill the agenda of neoliberal and authoritarian projects in the guise of populist promises, two important authoritarian shocks were introduced in the name of anti-corruption action and national economic unity. These shocks have thrown the Indian economy into, what Keynes (1963) called in the context of the Great Depression, a “colossal muddle.” These shocks have important class dimensions for Indian society.

First among the two shocks was the fake attempt to bring black money (approximately Rs. 5 trillion) back into the economy. This would further curtail illegal economic activities and the money so recovered was promoted to be used by the state to enhance the economic prosperity of the country. In addition to economic benefits, it was also presented as an important means to hit the anti-national terrorist activities through a clamp down on the illegal printing of Indian currency. This shock was introduced on November 8, 2016, when the government made an authoritarian announcement (no consultation with the RBI) of invalidating the high-value currency overnight. This action resulted in an acute shortage of money in circulation without any return to the economy. The authoritarian decision of demonetization, in place of healing the economy with all the collected black money, injured the informal sector activities gravely. This sector accounts for nearly 90% of India’s population and works as a major driver of aggregate demand in the economy. As per RBI (2018), of the Rs. 15.41 lakh crores worth Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 notes that were in circulation as on November 8, 2016, notes worth Rs. 15.31 lakh crores (99.3%) have returned to the banks—leaving the black economy unscathed. Instead, demonetization has imposed substantial costs on the majority of informal and small business sectors in the form of lost jobs, investment, and growth. It has destroyed petty production activities and purchasing power of informal sector workers, which has further depressed the demand for commodities and services produced in the economy (Ghosh, Chandrasekhar, and Patnaik 2017). The survey of 173,000 households conducted by the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) four months before and after the November 8, 2016, announcement of demonetization, found that demonetization was responsible for up to 3.5 million job losses in India (Bureau 2018).

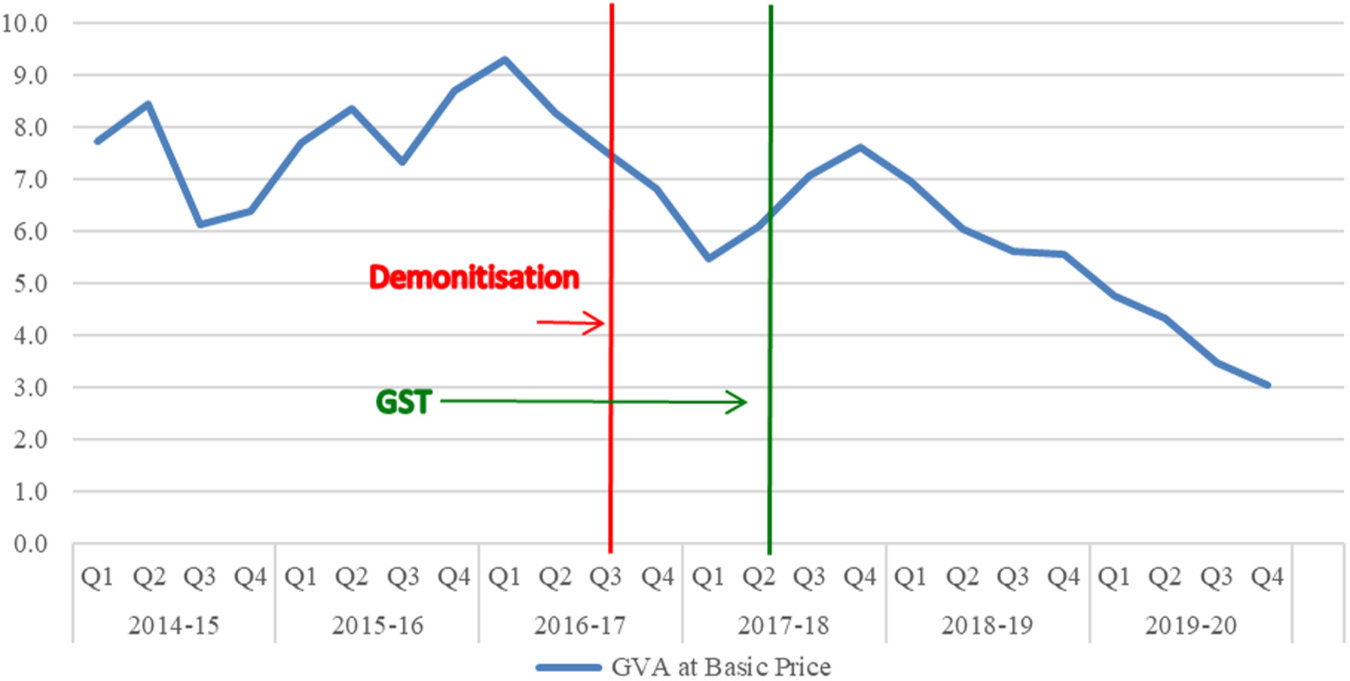

While the informal sector workers and small producers were still struggling to recover from the trauma of the first shock, the second authoritarian shock was injected on July 1, 2017, in the form of Goods and Services Tax. GST was not only an authoritarian assault on the constitutional rights of the state, undermining the federal structure in the name of “one country, one tax,” but also a neoliberal assault on the economic activities of the informal sector. The important question about introducing and implementing GST is: whose disposable income has ended up being cut and whose production and transaction cost has increased? The answer to this question is that GST has increased the transaction costs of informal producers because they have to set up the infrastructure required to fill the return at frequent intervals. The fiscal consolidation efforts through GST were based on the idea of tax neutrality, i.e., to ensure that total tax collection under GST remains the same as under the previous tax regime. To maintain this, Patnaik (2017) argued that this regime widened the tax base and increased the average tax rate on the informal sector in order to compensate for the reduction of the average tax rate on big corporate capital. The imposition of demonetization and GST has squeezed the transactions and activities of the informal sector. The economic consequences of both neoliberal authoritarian shocks are evident in the fall of GVA after their imposition (Figure 5).

Impact of Neoliberal Authoritarian Shocks on Gross Value Addition in India

Source: Calculated from RBI (2020).

While the aggregate economy has plunged into loss, the ruling capitalist class has emerged as a net gainer of these authoritarian shocks. It has helped the corporate and financial elites to expand their command over the production and exchange system. The class aspects of demonetization and GST can be examined from the fact that these authoritarian shocks have particularly hit small and informal businesses. As per a government statement in Lok Sabha, a total of over 6.8 lakh companies had been closed across India, which accounted for 36.07% of a total of 1,894,146 companies that are registered under the Registrar of Companies ( Economic Times 2019). At the same time, as highlighted above, the income of the super-rich section of the Indian capitalist class has increased many folds. The deflationary policy of demonization aided the capitalist class in the form of displacement and dispossession of production activities of petty and small firms due to a shortage of cash and a deficiency of demand for their products. Similar solicitude for the interest of the capitalist class was also apparent in the government’s implementation of GST, the distributional outcomes of which are straightforward. The introduction of GST has brought petty and small producers under the tax net and increased the unit cost of their products in comparison to big firms. These two authoritarian shocks have facilitated the seamless and simultaneous occurrence of the two processes highlighted by Marx (1992): first, a process of primitive accumulation of capital (through destruction of petty production activities); and second, a process of centralization of capital (through destruction of small capitalist producers) in India.

These mass income deflationary processes that have aggravated the depressionary tendencies in the economy are not what Keynes (1963) called “magneto trouble,” in the context of forces of the Great Depression of the 1930s or what Krugman (2008) explained as “technical malfunction” in an otherwise perfectly functional market economy. 11 Rather, they are an outcome of long-term austerity programs which have been well on their way since 1991 in general, and what Amartya Sen articulated, as a quantum jump of India’s political economy in the wrong direction since 2014 in particular. The peculiar feature of the austerity program of the authoritarian neoliberal regime is that it has eroded the standard procedure of deliberation, scrutiny, and critique for its rationality that, as Sen (2009) argued, nowhere passes the test of critical scrutiny and collective rationality—a precondition for a democratic society. The politicization and centralization of economic policies, pro-superrich policy framework and implementation and unchecked political power have not only seriously damaged the economic health of the country but, more importantly, have sharpened the economic and communal division in the society. The democratic deficit in political and economic decisions in India is an outcome of a corporate-sponsored authoritarian statist approach to the problems which require participatory deliberation. The participatory democratic process, articulated by Sen (2015) as an effective means of preventing mistakes rather than making head roll after mistakes, has completely disappeared from policymaking and implementation in India.

Conclusion

This article submits that the consolidation of the Modi-led BJP is an outcome of the complex relationship between the three pillars of authoritarian neoliberalism (the BJP, the RSS, and the national and transnational capitalist class), which rule over the political and economic systems of India. The failure of the Congress-led UPA to achieve the promised inclusive neoliberal agenda of delivering the benefits of higher economic growth to the poorest of the poor, coupled with widespread corruption, prepared the roadmap for the rise of the BJP at the central stage in 2014. By targeting this policy paralysis and corruption during the UPA regime, Modi secured the remarkable support of the national and transnational capitalist class in exchange for the promise to open all the remaining spheres of the Indian economy to private capital. In addition to this, the unreserved support that he received across class and caste played an important role not only in extending the BJP’s command over the Indian political system but also extended the control of neoliberal forces on India’s economic system.

The article has highlighted the serious implications of the evolution and consolidation of authoritarian neoliberalism for the Indian economy. The introduction of mass income deflationary policies initiated by the Modi-led BJP has resulted in a decline in gross capital formation and the saving rate, leading to an increase in involuntary unemployment in India. Further, the fall in employment elasticity due to excessive dependence on imported technology has pushed the Indian economy from jobless growth to a job-loss growth path. The article has highlighted that politicization, centralization, and pro-corporate implementation of economic policies have extended the network of a primitive type of accumulation in India. An increase in the magnitude of informalization, casualization, and dispossession are important symptoms of this. The article has also exposed the class aspect of neoliberal (ir)rationality-driven austerity measures and authoritarian shocks such as the low fiscal deficit, demonetization, and GST. The disproportionate advantage to the super-rich fraction of the capitalist class through authoritarian implementation of these policies has ruined the small and petty production activities along with a systemic increase in economic inequality. The outcome of this quandary of the Modi-led authoritarian neoliberal regime is that it has failed to deliver the promised economic gains such as higher economic growth, reduction in unemployment and promotion of distributive justice.

In conclusion, we want to emphasize the fact that the ideological and repressive state apparatuses of the contemporary authoritarian state are playing a detrimental role in diverting the attention of the public away from the economic consequences of authoritarian neoliberal rule. The Modi-led BJP has been using its ideological apparatuses to create a false consciousness in the name of race, religion, and culture with an objective to hide the concrete truth of economic catastrophe produced by the authoritarian and capitalist class alliance. Other state apparatuses that are quite visible in contemporary India are the repressive state apparatuses which function in the form of attacks on all types of freedom, clampdowns on those who oppose injustice, attack on minority groups, trade unions, farmers, intellectuals, and activists. These apparatuses and pro-superrich economic policies have become a necessary precondition in the contemporary regime to ensure the unregulated progress of primitive accumulation by the capitalist class at the cost of the majority. Therefore, at this juncture, understanding the economic consequences of contemporary rule is extremely important to expose the real enemy (neoliberal capitalism) that is flourishing under the shadow of authoritarian statism.