Introduction

[Saturday, 9:55 am: 5 minutes to event start]

It was the Startup Saturday event! People were streaming into the auditorium, hurrying through the aisles to grab seats. The business incubator had been running the event to a packed house for a few years. Today it was going to be streamed live for the first time. The guy with the video camera and laptop had come in much earlier. He was positioned in one of the aisles, making a few chairs unusable for seating. Some attendees seemed annoyed by his presence; most looked past him. He was too ordinary to be noticed – dressed in jeans-tees-sandals, focused squarely on the task at hand – almost in contrast with the buzzing auditorium filled with entrepreneurs and aspiring entrepreneurs who were there to attend a Marketing for Startups session, build networks and click selfies with the panellists. The quiet, unassuming videographer became a regular fixture for the next several Saturdays as live streaming of the events became a standard feature. His name was Rishi [name anonymized] – completely ordinary, completely missable among the hundreds of excited faces at the event.

Oblivion was not familiar territory for Rishi though. He was among an elite team of engineers at a large technology company just over a year ago. He had a fat paycheck, a promising career, and weekends to enjoy as he pleased. But here he was now, being an entrepreneur. His newly launched venture was in video communication, and the event provided an opportunity to test the minimum viable product. Testing was essential to building his product and achieving sales and funds. When he pitched to customers and investors, he exuded confidence, charm and passion as the CEO of a promising startup incubated at one of the top business incubators in the country. At other times, he had mundane but mandatory work to attend to, such as that of a videographer. Rishi frequently reminded himself that he just needed to keep going, step by step, through the mundane in that fund-less, revenue-less oblivion. He knew he had to be patient.

[Three years later]

Rishi’s venture was acquired in a multi-million-dollar deal. His face is splashed across all startup news channels. That missable face is now the talk of the town. He will be mentoring entrepreneurs at the same incubator where he was once being incubated himself. He is a panellist at an edition of the same event where he used to test his product. He has much to share about his journey – how he discovered the idea, passionately pitched for funds and customers, diligently built a technologically advanced product, suavely negotiated the acquisition, made his millions, etc. Will he remember to share how patient he had to be through the stretch of fund-less, revenue-less oblivion? Will he remember to talk about patience – an essential ingredient of his success story?

(Based on a study of entrepreneurs at a business incubator)

Days like Rishi’s Saturday are not uncommon in the life of the founder of a fledgling startup. For instance, the founders of the Indian unicorn, Flipkart, now billionaires, are known to have ‘spent interminable waking hours promoting their new startup and feverishly scanning their inboxes for emails’ during the early days of starting up (Venugopal, 2015). Their promotion activities included making posts on blogs and forums in the hope of making a sale. Fulfilling a rare order in those early days would often find the founders scanning bookstores across the city, searching for an item, and mailing it personally to the customer, come rain or shine. The first full-time Flipkart employee was hired nearly two years after the venture was launched. It is hard to imagine that patience would not have been in the founders’ minds when they were making online posts, scanning emails and mailing books while waiting for an uncertain success. Patience, the propensity to wait calmly in the face of frustration and adversity (Schnitker, 2012), has largely been ignored in scholarly and populist writings about entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs.

The widely held perception is that entrepreneurship requires traits such as risk-taking, drive for achievement, perseverance (Frese and Gielnik, 2014), and emotions such as passion, excitement and zeal (Cardon et al., 2009) – all qualities with their roots in action and excitement. However, on most days, even Superman lives and works like Clark Kent! 1 Venture building can mean engaging in a mixed bag of activities that includes, on the one hand, the dramatic and daring actions, taking a leap into the dark, and raising funds or pitching to customers, and on the other, mundane and monotonous tasks such as making calls, writing emails, recording videos – all of which are performed in the shadow of uncertainty with neither a prescription for the activities that are critical nor a known timeline of engagement that would guarantee success. What traits, behaviours or experiences keep the entrepreneur going through the long, challenging period from initiation of organizing activities aimed at starting a new venture until the venture is sustainable?

In an inductive, longitudinal study of nascent entrepreneurs in the early stages of venture building, we find that patience, an unassuming trait that implies the ability to endure life’s grand challenges as well as daily hassles calmly (Schnitker, 2012), can influence why some entrepreneurs hold course while others give up. By examining the behaviours and activities of entrepreneurs during a hitherto understudied critical phase in the founding process, the study finds evidence of the importance of patience for early-stage entrepreneurs. The paper introduces the concept of ‘entrepreneurial patience’, grounded in data, and discusses the possible reasons for the concept being neglected in the literature.

Background

New ventures have a high chance of failure in the first few years after launch (Aldrich and Ruef, 2018). The nascent entrepreneur faces complexity, uncertainty and risks in finding resources to launch an idea into a venture and then to grow the new venture into a sustainable business. They have limited experience in starting and running a business and lack the track record and credibility to attract customers, investors and new employees (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006). Between having an idea to pursue and launching the venture or deciding not to launch, an entrepreneur engages in various venturing activities to evaluate the feasibility and desirability of building the venture. Besides complex tasks, resource-constrained founders often go through long periods of performing tedious tasks that may appear mundane, but are the building blocks for the more abstract and glamorous exploration and exploitation activities generally associated with venture building (Mueller et al., 2012). Researchers, policymakers and practitioners have striven to understand what sets successfully created ventures apart from those that fail to take off or shut down in nascency by examining the venturing activities of founders, entrepreneurial traits, emotions, skills, behaviour. However, most studies have relied on retrospective narratives and responses of successful entrepreneurs, making such insights prone to hindsight bias, self-justification, and survivorship bias (Cassar and Craig, 2009; Aldrich and Ruef, 2018).

Calls to study entrepreneurship as a journey that takes time as opposed to a snapshot have largely gone unanswered (McMullen and Dimov, 2013; (Bergman and McMullen, 2022)), though it is widely acknowledged that studying nascent entrepreneurs at the time of venture creation mitigates the biases associated with retrospective data (Cassar, 2007). Cardon et al. (2012) argue that even emotions should be examined through the entrepreneurial journey to understand what happens ‘in the middle’ (between opportunity identification and exit/shutdown). New venture gestation can take several years (Carter et al., 1996). Prior studies based on survey data find that nascent entrepreneurs who eventually gave up undertook a similar number of activities in the first year as those who launched their ventures. They suggest that giving up was a result of a flawed business plan or lack of creativity in solving problems (Carter et al., 1996). Mueller et al. (2012) posit that with the notable exception of the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (PSED), which captures more than 30 different activities in which entrepreneurs might engage, most studies build on self-reports, rely on vague behavioral constructs, or capture only one selected behavior at a time (e.g., planning, registering a business, or acquiring resources). The effect of engaging in a range of startup activities repeatedly in an uncertain and ambiguous journey, is largely unexamined. Our longitudinal study follows an entrepreneur’s journey from idea to starting up (or giving up). Our qualitative study examines early-stage entrepreneurs’ experiences and provides a unique opportunity to understand why some founders can hold their course through the roller-coaster of the entrepreneurial journey and why some give up.

Methodology

Context and data

The research was conducted as an inductive, longitudinal, multiple case study of nascent entrepreneurs incubated at a leading business incubator in India. The purpose of the study was to investigate the lived experiences of the entrepreneurs to understand how they benefited from being part of the incubation program and how it affected their entrepreneurial experience, and their decision to persist with venture creation (or to give up).

Business incubators assist early-stage entrepreneurs in converting their ideas into sustainable enterprises by providing them with resources, such as low-cost office space, business advice, professional services, capital and access to networks of customers, collaborators and investors. Most incubators have rigorous selection criteria for admitting entrepreneurs into their programmes. To a certain extent, this ensures that the entrepreneurs selected to join these programmes are committed to working seriously on their ideas. They are not just dilettante dreamers who consider themselves entrepreneurs in the making, but take little action to become entrepreneurs (Parker and Belghitar, 2006). For an entrepreneurship researcher, an incubator provides an ideal site to study the insides of new venture creation. It provides a concentrated pool of entrepreneurs who are in the early stages of venture building, attempting to find the resources to turn their ideas into reality. Studying such entrepreneurs offers a way partially to overcome some of the most common obstacles in entrepreneurship research – examining only successful ventures and missing out on the early stages of the venture-building process as it happens.

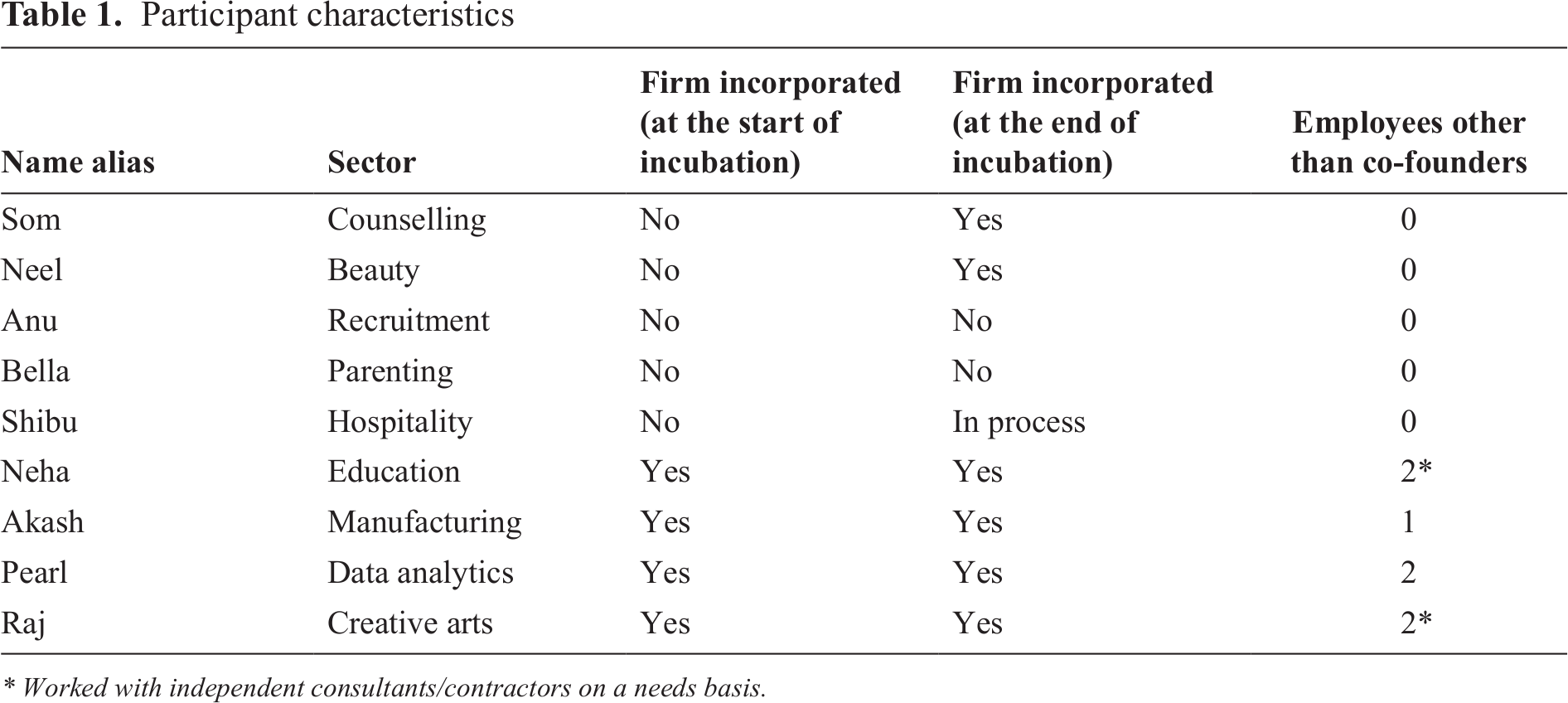

Even a single-case study can often be explanatory and not merely exploratory or descriptive (Yin, 1994). While there is no ideal number of cases that ought to be studied, and studies which focus on a single case have produced results, a number between four and ten is usually found to work well (Eisenhardt, 1989). This also seems to apply to qualitative studies of business incubation, where the sample size ranges from a single case study (Baraldi and Ingemansson, 2016) to four cases (Monsson and Jørgensen, 2016) and six case studies of entrepreneurial firms in an incubator (McAdam and Marlow, 2008). Eisenhardt (1989) suggests that while focusing on fewer than four cases is unlikely to be convincing in their empirical grounding, more than ten cases can produce complex and voluminous data that can be difficult to handle. Here, proceeding with nine willing participants (see Table 1) was deemed appropriate and sufficient for the study. The entrepreneurs in the study were neither earning revenues nor had they received any external funds.

Participant characteristics

Worked with independent consultants/contractors on a needs basis.

Four formal interviews were conducted with each participant over 12–13 months, from the start to the end of the incubation programme. Frequent interviews allowed us to capture and understand entrepreneurs’ perceptions throughout the period, providing insights unaltered by the degree of success of the idea at the end of the study period and making the study less susceptible to retrospective bias (Pettigrew, 1990). The interviews were semi-structured in that we kept a list of topics to serve as a guideline, while ensuring conversational flexibility to accommodate the richness inherent in the participants’ experiences. The interviews generally lasted between one and two hours. We found that asking if the incubator helped them in any way tempted tick-box answers that listed the generic resources available, irrespective of whether the incubatees had used them. We stayed away from leading questions and instead used a mix of open-ended questions and probe questions that start with How or Why and cannot be answered with a simple yes or no. Examples would be: What are the most pressing problems (personal, professional, financial, etc.) you have faced while building your venture? How did you solve these problems? Did the incubator help you find solutions? If so, how? We found that asking about key issues they were facing and how they resolved them provided most insight into their activities, their emotions, their choices, the incubation resources they used and the various ways in which they sought resources within or outside the incubator. In the terminology of Gioia et al. (2013), we were a ‘glorified reporter’ giving voice to informants as they articulated their thoughts, intentions and actions.

Analysis

All the interviews were conducted in English, recorded and then transcribed. Some participants were not fluent in English and frequently used their mother tongue, Hindi. Since the interviewer is fluent in English and Hindi, the answers were translated into English while transcribing and verified by at least two people. The English interviews were transcribed verbatim. Any pauses, omission of words, disjointed sentences, or sentences that trailed off were noted using ellipses to retain the speaker’s sentences accurately. Some conversational grammatical errors in participant quotes have been retained. All transcripts were uploaded to Atlas.ti, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS), to simplify data management and ensure discipline and rigour in analysis. The data analysis followed an iterative process of inductive theory-building research (Gioia et al., 2013; Charmaz, 2014), involving moving back and forth between the data and emerging categories. Using Charmaz’s approach of coding with gerunds, we focused on process and action. For instance, using codes such as ‘Becoming patient’, ‘Accepting the slowness, ‘Feeling bored’ helped further break down the transcripts into what the incubated entrepreneurs were doing and thinking rather than classifying them into types of individuals. This ensured that the focus remained on what was actually happening instead of our own pre-conceived conceptual leaps. After that, we engaged in focused coding – studying and assessing each participant’s most significant initial codes. This allowed the emergence of second-order themes such as gaining tangible benefits (workspace, first sale, hiring, pitch improvisation) and intangible benefits (self-confidence, legitimacy for an idea, accountability to show progress, learning patience) from incubation, gauging the feasibility of the business idea and the desirability of the outcome. By plotting the significant codes chronologically in a timeline-like fashion to depict the entrepreneur’s journey through the incubation period, a visual representation of the connections among the codes was generated. Juxtaposing the coded journey of each participant facilitated the emergence of concepts grounded in data.

Once we had identified that ‘patience’ was a recurring theme, we returned to the data to examine what function patience serves in the entrepreneurial process. With the intent of staying close to what the informant was saying, we reassessed the use of words (such as patience/patient, bored/boring, slow, routine, time, anxiety, passion, perseverance, peace, feeling) to understand how entrepreneurs were describing their feelings and actions. The idea of ‘learning to be patient’ was dominant in the early stages when entrepreneurs struggled to make sales and had neither earned revenues nor received external funds. What stood out conspicuously was that reference to patience declined and eventually disappeared once entrepreneurs had made progress in their journey and had received some tangible external validation in the form of revenue or funding. Thus, we find that the idea stage entrepreneurs – Som, Neel, Anu and Bella – refer to developing patience as an important benefit of being mentored at the incubator. In contrast, Shibu, Neha, Akash, Pearl and Raj – who had moved beyond the idea stage into selling to customers – had accepted the slowness inherent in the venture-building process and did not explicitly refer to patience. We searched extant literature concerning entrepreneurial emotions and traits to develop deeper conceptual insights into data stemming from the lived experiences of entrepreneurs. This iterative and abductive process provided the basis for proposing entrepreneurial patience as a key concept in the early entrepreneurial process.

Findings

The period between idea conception and the initial stages of venture emergence is when entrepreneurs perform specific tasks and evaluate the feasibility and desirability of building the venture in some detail. Early-stage entrepreneurs find that building the venture will often require routine activities and monotonous work without immediate, tangible returns. The decision to proceed with building the venture is affected not just by the anticipated outcome (returns expected if the venture succeeds), but also by willingness to go through the atomic venturing activities. Putting the plan into action makes clear the grind behind the glamorous image of being an entrepreneur. For instance, one of the participants in the study, Anu, was building a platform for hiring employees with a certain specialized experience. While talking about her venture, Anu would use terms such as ‘niche’, ‘exclusive’ and ‘pain killer’. However, at its core, the work required her to provide employment opportunities for a certain set of job seekers. When she tried to attract the first few customers following her mentor’s advice, she realized how ordinary her work was considered to be by the potential customers, mentors and collaborators she approached.

They wanted me to be a placement agency. I had so many ideas in mind that I wanted to do. This is not what I wanted. If I get labelled as a placement agency, whatever I have earned in the last 14–15 years of my career [will be lost] … I am exclusive. I will not be able to get over this tag. (Anu)

New business ventures have often begun from scratch, requiring entrepreneurs to work up from obscurity to an unpredictable and unguaranteed prominence. The sense of being ignored and disregarded, day after day, while striving for uncertain success, is an experience that not every fledgling entrepreneur has the patience to endure indefinitely.

Whenever I reached out to the industry, the corporates or startups for the placements consultants, they treated me like a side artist. Even if you are specialized in a field, you get ignored so much. (Anu)

Bella liked to call her venture a ‘curated e-commerce platform’, but while trying to sell products, she felt she was seen as no more than a distributor, which she found unpalatable and very different from her idea of an e-commerce entrepreneur.

That was when I was actually evaluating if I am doing the right thing … I felt this is not working out very well and long-term perspective, it looks like I am going to become a stereotypical distributor. And I don’t think that is the right way for me. (Bella)

Once the entrepreneurs start acting on their business plan, they often realize that they do not have the patience for this kind of work, that they are unwilling to endure the mundane tasks involved or bear the uncertainty of rewards that might be reaped only in the distant future. For instance, Anu was not willing to tackle routine, boring tasks or to follow up potential customers. Bella realized that she preferred her corporate salary to waiting for her venture to take shape, if it ever did.

Regular boring thing … Operations … I hate calling up people and following up. If any work becomes repetitive or routine, then I start getting bored and don’t feel like doing it. (Anu)

I think it was just one thing that I have constantly been asking myself, can I go back to something and do it for the next 10 years without getting bored of it … The straight answer to that was no. He [her mentor] wanted me to work on that for the next five years. If I had the patience to work on something for five years and not expect anything in return, then I would have been in corporate job. At least I would still earn a salary. (Bella)

Those who persist reconcile themselves to the slowness inherent in the process of building a sustainable venture. Som’s venture was in the field of premarital counselling and marriage wellness, a domain unheard of in Indian culture. The mentors frequently reminded Som about the time and effort it would take for the venture to gain acceptance and customers.

It is a long-haul thing. It is not going to be overnight … to expect I invest X and then I get XYZ or X times whatever, it takes time. I am prepared. Three to four years is what they [mentors] say that it will take in terms of having people throng at your doors. Until then, I will have to hold on to my horses (Som)

Entrepreneurs find solace in feedback from mentors who warn them about the time needed to make money. Entrepreneurs constantly have to remind themselves that success is unlikely to come quickly.

I have to write it down – we are not going to be so jumpy about the numbers that come in, I will be more content with the shaping of the service. (Som)

The granular tasks involved in setting up a business can feel different in the execution from how they felt in the planning. This is manifest in the difference between thinking about being patient and actually being patient. For instance, at initiation, Bella opined:

I want to have at least x number of offline sales, bazaars, and events, and only then I will make a conclusion whether this is a viable thing to do in this way or change. (Bella)

However, a few months later, Bella’s resolve to be patient changed after the very first sales event.

I had an offline event at a corporate fair. I wanted to do that to validate whether there is an actual business model around this. That didn’t go too well. I didn’t even recover my rental costs. And the footfall was almost about 800 people. [If] I was not able to even recover my cost with 800 people, then it didn’t look like it was going anywhere. (Bella)

Neither could Anu stay motivated through the granular tasks of constant interaction with the team and potential customers.

Team management, team building … I find it boring. As if they are eating my head, wasting my time … To follow up with people – I can’t do that every day (Anu)

However, entrepreneurs who did persist made concerted efforts to stay focused on the granular tasks, day after day, even when the tasks were not to their liking.

I am not a marketing person, I am really not a people’s person. I prefer sitting on my own, doing my own thing. I am not somebody who would like go out there and tell people, talk about it, but it’s inevitable, I have to do it… making these things happen, getting so many people to come here and watch, getting people to come here and perform. Very stressful of course but the end of the day when you see this happening, it’s kind of, yeah maybe it is worth it. But there is a long way to go. (Raj)

Learning patience and reconciling themselves to the slow-yielding yet demanding process of venture building emerged as dominant themes reported by all the participants. However, ‘making peace’ with reality is easier said than done. The period without any feedback in the form of customer engagement, revenue or funds is tough. Offering the product or service to non-paying, reluctant users can discourage and compel entrepreneurs to re-evaluate and re-plan their activities.

I was extremely worked up that only 6 people came or only 4 people came for the workshop. But it’s okay. It will take time. I am not going to be very worked up, I am going only to make sure that the team is formed, the service is formed. Meanwhile, I’ll keep running to get people to come into every session. (Som)

At this stage, the incubator’s support cushions entrepreneurs from buckling under the burden of generating return on investment. While the incubator’s support may not reduce uncertainty in the journey, it can help increase the entrepreneur’s ability to be patient while building their idea and to bear the uncertainty of working towards a distant vision.

Maybe I would have given up earlier because I wouldn’t have seen that traction. But here, I have understood that traction wouldn’t come immediately, so that’s important. So I may have given up if I had not got the clarity or somebody with vision say – it is okay, it will take you 3 to 4 years for you to have this. Without any kind of ROI, I would have probably buckled. (Som)

Neel’s venture aimed to establish service standards and certification in India’s highly disorganized beauty industry – an idea that would take time to find credence and customers.

Every time the mentor kept asking me. He said, ‘See, yours will take time. What preventive healthcare was in hospital sector, you are trying to get the same thing in this sector or maybe later other unorganized sectors’. (Neel)

Every time I heard people saying yeah this is good, you will need three years, keep up, do it, in three years, this will pick up crazily – those things really help when you are in that initial stage that okay this has more validation, okay somebody else as well believes in it. (Shibu)

Learning patience to deal with the routine and mundane, and to wait calmly for returns, accepting the slowness inherent in the venture building process, and not buckling under the pressure to generate revenue were among the significant benefits of incubation the entrepreneurs reported.

We are projected to break even in the 5th year. This venture is a new category that we are creating. I was not at peace with it then, but now I am at peace with it. Because I see it. That’s how it is. (Som)

I think now I am more accepting of change and things not going the way they are supposed to than in the beginning. So, yeah … I have become a little better at letting things gain their own pace. (Akash)

Discussion

Patience involves tolerance of people, hardships and daily hassles that may be unpleasant and frustrating (Schnitker et al., 2017). It is required in mundane activities, such as answering phone calls, and in more significant situations, such as building a venture. Patience facilitates goal pursuit and is especially crucial to well-being when one faces difficulties and obstacles (Schnitker, 2012). Having patience promotes workplace performance through increased productivity, better decision-making, and enhanced interpersonal relationships (Comer and Sekerka, 2014).

Those entrepreneurs who discontinued working on their ideas admitted to a lack of patience with doing the tedious tasks required, day after day, and while waiting for years before their efforts would generate tangible returns or even credibility. The general belief is that entrepreneurs must act fast or risk losing opportunity (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006). The intense pace of performing multiple tasks to survive and to progress towards an uncertain future might make it appear that patience is inconsistent with being an entrepreneur. Conventional thinking has insinuated that patience delays goal achievement, that the patient entrepreneur forfeits the competitive edge (Comer and Sekerka, 2014). Entrepreneurial behaviour is frequently associated with such values as independence, creativity, ambition and daring (Walton, 2016). This study finds that entrepreneurs, assisted by their mentors’ support and the growing clarity of their venture’s growth potential, consciously work to develop patience. They have constantly to reinforce themselves, ‘to avoid getting jumpy about the numbers’ – that is to be patient through the period of no or low customers. Nascent entrepreneurs in this study frequently invoked patience as a critical strength during the early pre-revenue, unfunded stage of building their ventures.

The overwhelming evidence of patience in vivo in all the participant narratives in the study perhaps begs the question: why is patience unexplored in the discourse on entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship? Three plausible reasons are worth discussing. First, there is a certain aura of heroism around entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is romanticized as a form of ‘creative destruction’ (Schumpeter, 1934), a journey fraught with uncertainty and risk (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006), and ‘a tale of passion’ (Cardon et al., 2009). The central actors of this tale, the entrepreneurs, are hailed as subversives who disrupt the status quo (Smilor, 1997), confronters with fervour and ardour (Baum and Locke, 2004), as ‘passionate, full of emotional energy, drive, and spirit’ (Cardon et al., 2009), as unusual and heroic personalities (Aldrich and Ruef, 2018), ‘hustlers, hipsters and hackers’ (Rudic et al., 2021), and agents of ‘urgent, unorthodox actions’ in the face of challenges and adversity who hustle their way to success (Fisher et al., 2020). Entrepreneurs are new-age celebrities – symbols of wealth, power and success – who have captured the popular imagination by building mega-successes out of unknown ideas (Wooldridge, 2009).

Entrepreneurship has been portrayed as an ‘emotional roller-coaster’ (Shepherd and Patzelt, 2018). At the forefront of these emotions is entrepreneurial passion which, according to Smilor (1997), is ‘the most observed phenomenon of the entrepreneurial process’. Cardon et al. (2009) find that entrepreneurial passion is associated with enthusiasm, zeal, joy and fire in the belly and conclude that ‘passion invariably involves feelings that are hot, overpowering, and suffused with desire’. In this larger-than-life portrayal of entrepreneurial life, it might have been easy to miss patience, ‘a quiet character trait, lacking the drama of courage’ (Kupfer, 2007). There is a general tendency in entrepreneurship research to examine retrospective narratives of entrepreneurs who have succeeded, resulting in what is known as a success bias (Aldrich and Ruef, 2018). Retrospective reconstruction is prone to the taking of creative liberties as ‘people like to put themselves at the centre of the action – inflating their importance’ (Aldrich, 2001) and patience might seem too ordinary to be narrated in an extraordinary success story. Bhave (1994) suggests that in hindsight the entrepreneurs ‘hardly talked about organization creation’ and how they overcame the difficulties of resource gathering at early stages. They dwelt on environmental factors or technological and market uncertainty and narrated resource struggles as ‘humorous war stories’. It is possible that the subtlety of patience has not found a place in narratives that have formed the basis of most entrepreneurial research.

Secondly, there is a dearth of longitudinal, processual studies of entrepreneurship (McMullen and Dimov, 2013) that examine the micro-behaviours that entrepreneurs adopt under uncertainty (Fisher et al., 2020). Entrepreneurial activities are often bucketed into impressive roles of inventor, founder and developer an entrepreneur plays (Cardon et al., 2009). However, largely ignored by the empirical literature are the micro-processes that underlie the abstract roles attributed to an entrepreneur (Haynie et al., 2009). Entrepreneurs rarely have a job description (Mueller et al., 2012). During the early stages, the founder of a resource-constrained startup is likely to be the CEO as well as the janitor. Mueller et al. (2012) categorize an entrepreneur’s everyday activities as atomic, molecular, molar and galactic. For instance, in Rishi’s case, an atomic action of videography implies a molecular activity of user testing, a molar function of product development and a galactic form of exploration. Abstraction of the atomic action into a galactic goal, while useful for eventual theory generation, can obscure the raw characteristics of those actions. Rishi was engaging in exploration through new product development, for which he was performing user testing by ensuring live streaming of the event and being the camera guy at the event. When it is time to tell Rishi’s success story, being an explorer and inventor will likely be more entertaining and inspiring than being the missable videographer. Similarly, in Flipkart’s big billion startup story, the boardroom heroics of founders are likely to take centre stage rather than their mundane attempts to gain customers, patiently for months.

Thirdly, the study shows that entrepreneurs’ reference to the importance of patience is temporal. The allusion to patience is prominent in their narratives during the pre-revenue, unfunded early stages of venture building. It wears off over time when they receive tangible, external validation through sales or funding. We notice this in our study as respondents’ references to patience decreased once they had made progress in their ventures or had significant validation for their ideas. Temporal instability can be hard to capture as, in most studies of entrepreneurs, the number and spacing of data gathering are determined by practical considerations (Gielnik et al., 2014). Because of frequent interviews and the study’s longitudinal design, we could capture patience in this study. If the entrepreneurs’ narratives had been gathered at an interval that extended beyond when they received external validation or decided to give up, the role of patience in their journeys might not have been evident.

Conclusion and Implications

It took me 20 years to be an overnight success. (Shah Khan, Indian film star quoted in Ghosh, 2011)

Many nascent entrepreneurs never actually start a business. During the early stages after opportunity identification, entrepreneurs evaluate the venture idea and engage in various venturing activities to gauge the feasibility and desirability of building the venture. Some endure, and some may fold under the pressure and uncertainty of the process. The popular press and academic writing have favoured the image of an entrepreneur as a swashbuckling and passionate personality. This paper steers the conversation towards a benign virtue that does not have the fire of passion or the thrill of risk-taking, but is significant in its impact on a nascent entrepreneur’s decision to persist or give up. The study extends the entrepreneurship literature by introducing the grounded concept of entrepreneurial patience. Future research could operationalize entrepreneurial patience as a construct and consider including it in questionnaires and surveys to examine its impact on goal attainability and venture emergence. Entrepreneurship scholars have persistently called for study of entrepreneurship as a process that occurs over time (e.g., McMullen and Dimov, 2013). Qualitative, longitudinal research is uniquely placed to unravel elements which were not initially considered but proved to be significant in the data gathered (Fisher et al., 2020). This paper is an artefact of such research as it shines the ‘spotlight on the actual actions of entrepreneurs’ (Venkataraman et al., 2012).

Practical Implications

The depiction of entrepreneurial careers as full of excitement and daring fails to capture the importance of patience in the early-stage entrepreneurial process, when founders have to tackle the repetitive, mundane tasks that underlie the extraordinary achievements associated with successful entrepreneurs. The prevalence of heroism, passion and excitement in narratives of entrepreneurial endeavour can obscure the importance of patience in the entrepreneur’s daily grind. There are likely to have been years of effort behind every overnight success. What it takes to be an entrepreneur is not just bold heroism but also placid patience. Scholars, practitioners and policymakers should realise and acknowledge that the aspiring entrepreneur must work long hours as Clark Kent before soaring to the heights as Superman.