The present work utilizes the rich photographic collections of the Herrnhut archive, Rijksmuseum and Tropenmuseum to explore alternative ways of understanding the colonial Indian labour diaspora, to infuse new meanings into old pictures and to draw upon the reinterpretation of historical images to reframe personal female migration stories from an artistic perspective. This essay presents an overview of the photography of colonial subjects in India and of her diaspora, and discusses the symbolism and representations of selected case studies of individuals and groups in the Dutch colonial territory of Surinam. From this analysis, the author presents the significance of her findings for the evolution of her own work as an Indian woman of diaspora heritage exploring new ways of articulating complex personal and group identities through the medium of exhibitions and installations.

The Collections

A. The Herrnhut Archive, Germany

The little known Völkerkundemuseum Herrnhut and its archive derives from the work of Protestant missionaries who went into exile during the Counter-Reformation. From 1732 Herrnhut Missionaries were active in places as far afield as the Caribbean, Greenland, South Africa and North America. Today the missionaries have disappeared but their collections and photographs live on. The mission was active in Surinam from as early as 1735. Their 19th-century posed photographs of Indian migrants will be discussed in this essay.

B. The Tropenmuseum

This ethnographic museum was founded in 1864 to showcase the Dutch overseas possessions. The collection of more than 150,000 photographs, many of which were inherited from the Ethnographic Museum Artis, includes photographs of Indian migrants to Surinam, some of which are described below.

C. The Rijksmuseum

Since 1993 the Rijksmuseum has been building a photo collection that now comprises 150,000 photos: special examples from international photography from 1839 to the present day, with accents on Dutch, French and American photography, houses 2,670 photographs from Surinam depicting Indian migrants.

New Meanings from Old Pictures

Before discussing the photographic archive, it is necessary to provide a brief overview of the subject under review: Indian migration to Surinam, a Dutch colony, also known as Dutch Guiana, adjacent to British and French Guiana. Between 1838 and 1917, 40,000 Indians migrated to Surinam. They generally boarded a ship departing from the port of Calcutta sometime between 1873 and 1916. On arrival in Surinam, they started working as indentured labourers on a five-year contract. After renewal of the contract and another five years of very demanding work on the plantations, they could make use of a ‘free passage’ and return to Calcutta.

Photography was effectively introduced to India in 1868 when seventy-three album prints were taken that were published over successive years under the title The People of India and which showcased individuals and groups of Indians. The method of photographing people at this time was mostly with the intention of creating systematical order with the use of plain backdrops and props; furthermore, certain artefacts were used to symbolize different occupational categories. The People of India is a project of documentation of race and class of the people of different states in India. The project was commissioned by the British administrators, and besides the documentation from a colonial anthropological perspective questioned how to control the people and maintain British rule in India. Photography had been used in anthropometric studies of people in the Andaman Islands as described by Christopher Pinney: ‘With the use of grid paper the sizes of body parts and further anatomical studies were made by the phrenologist W.E. Marshall treating the people as primitive animals.’ Likewise enslaved peoples were photographed in order to study their anatomy and physical characteristics, and various anthropometric studies show observations of the ‘savages’. 1

The indenture diaspora to the Caribbean islands, Fiji, Mauritius, Réunion and South Africa in the 19th century introduced a multiplicity of subjects who would be ‘exocitized’ in the same way for tourist postcards. ‘The Caribbean postcards of indentured women bear traces of this lineage’ writes Gaiutra Bahadur in her interesting article on postcards of the British Empire. Bahadur describes how

in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Indian women were photographed in Jamaica, Trinidad, and British Guiana for a thriving postcard industry built on marketing the Caribbean as a holiday destination for Western tourists. During the colonial period, the Caribbean islands had developed a reputation as hot-houses of hard drink and yellow fever, virtual graveyards for white men. Determined to change this perception, colonial administrators launched a concerted campaign to sell the Caribbean as an ‘exotic but safe’ destination, a message well represented by images of beautiful women who were once among the British empire’s most denigrated laborers. 2

The first and oldest photograph (Figure 1) taken in Surinam is held in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and portrays a couple from a mixed background. It dates from 1846. The woman Maria Louise de Hart (born 1826) and the man Johannes Ellis (born 1812) are photographed seven years after the medium of photography started to exist and is a daguerreotype. 3 De Hart was the daughter of a freed ex-slave and a Jewish plantation owner and is therefore from a mixed background. Johannes Ellis was the mixed-race son of Abraham de Veer who was the governor of the Dutch Gold Coast (now Ghana) and a Ghanaian woman, Fanny Ellis. 4 This early photograph serves as a symbol for the multicultural society that Surinam had become by this time and remains today. According to the online source ‘two Americans travelled through Surinam to make a series of daguerreotypes’ of which the portrait of this iconic couple has become a celebrated example. Despite their multicultural origins, the couple wear Western clothing in the style of the colonizers. They would later migrate to the Netherlands, where they resided; their clothing in the daguerreotype signifies the total cultural adjustment that later on enabled them to live among Dutch society. The perspective of the American photographers is here not to portray the ‘savage’ but to mimic the portraits of Westerners as they were then made and thus does not define the couple in another categorization or system as had been intended in The People of India. This might well be because of the important connections and status of the white Dutch fathers of the couple, to whom they are assimilated.

In the new life in the Caribbean, women were faced with an unstable family life, within their own community. Linguistic, religious and geographical differences led to the disappearance of the caste system. 5 Caste became less significant for both gender and marriages between different castes became common. The practice of ‘untouchability’ disappeared and this resulted in changes compared to India. The Indian migrants became aware that during the process of migration, caste is not a ‘fixed social structure’ they did not have the power to change but they did redefine their caste structures. ‘Low caste servants grabbed the slightest opportunity, though with certain limitations, to abandon the traditional caste system and adapt semi-Western ways’ (Roopnarine, 2006, p. 71). Furthermore, Niranjana states, ‘the caste surnames existed but lost their meaning as status markers and since in most cases the labourers had no surnames at all, they could in the period after indenture take on any surname of their choice even suggesting higher caste’ (Niranjana, 2006, p. 41).

From the ‘types’ of women constructed in the time of recruitment until the settled migration group in Surinam, the identity of women must have undergone diverse amendments. As has been quoted by Niranjana an emigration officer of Surinam wrote in 1877–1878 about the recruits gathered in the depots prior to departure: ‘Their number was considerably augmented by a batch of dancing girls and women of similar description with their male attendants. These people laughed at the idea of labouring as agriculturalists’ (Niranjana, 2006, p. 62).

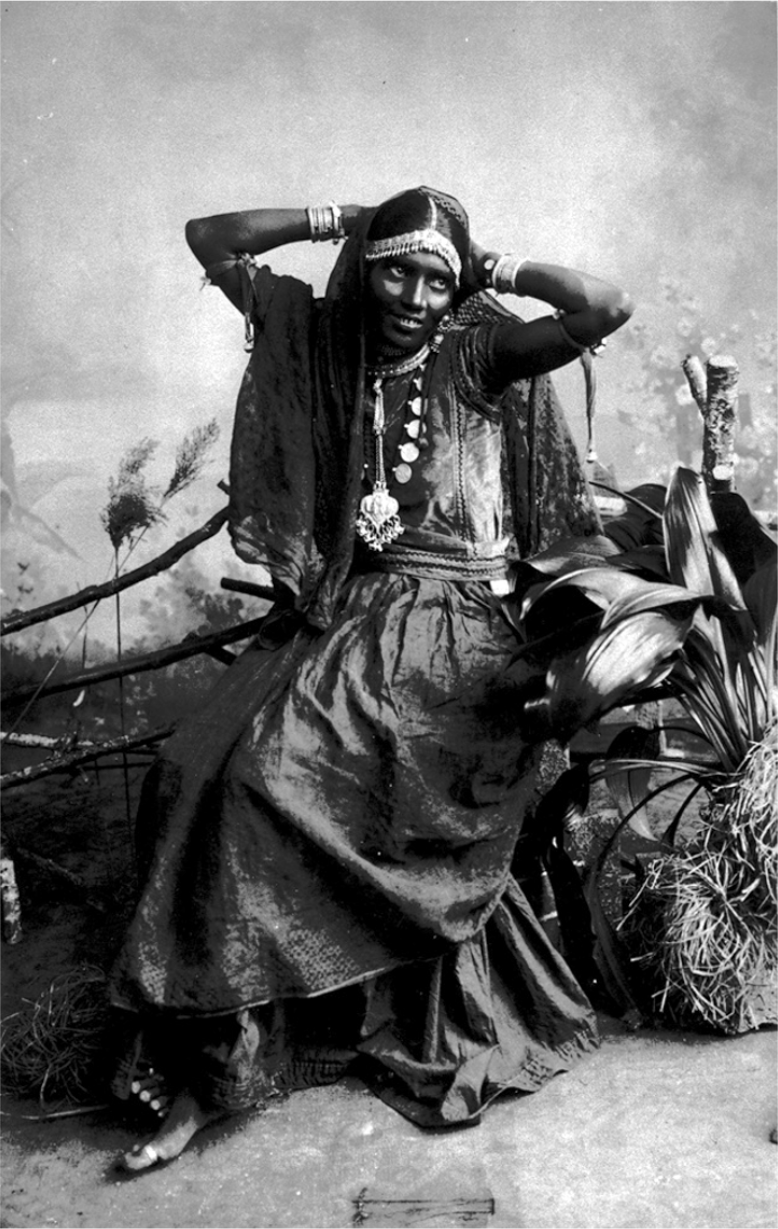

Tropenmuseum Collection, filenumber TM-60005820, Untitled, Suriname photographer unknown, circa 1900.

The idea of these ‘types’ of women being prostitutes is described by different colonial reports and when these women had to function in the colonies abroad they used sex as a tool of power and status within the colony and, according to Niranjana (2006, p. 62), the women had ‘great freedom of intercourse’. Compared to the men, the women always received half or less payment and therefore were dependent on men in the colony. The financial dependency is thus a motivation for women to break through traditional patterns of behaviour. Refiguring identity among females must have led to more diverse realities than the idea of the ‘lower caste’ having low morals and the ‘higher caste’ having higher ones. With the freedom of a new life, the first generation of women could choose their own partners regardless of their caste and, furthermore, became sexually more liberated. The image of the woman in Figure 2 seems to incorporate a feeling of freedom, although sexual liberation cannot be conveyed solely through their agency within the context of representations of studio constructions where this liberation is ‘staged’. In these photographs the construction of the ‘lower caste’ women as ‘prostitutes’ or ‘decorative objects’ seems to be imposed.

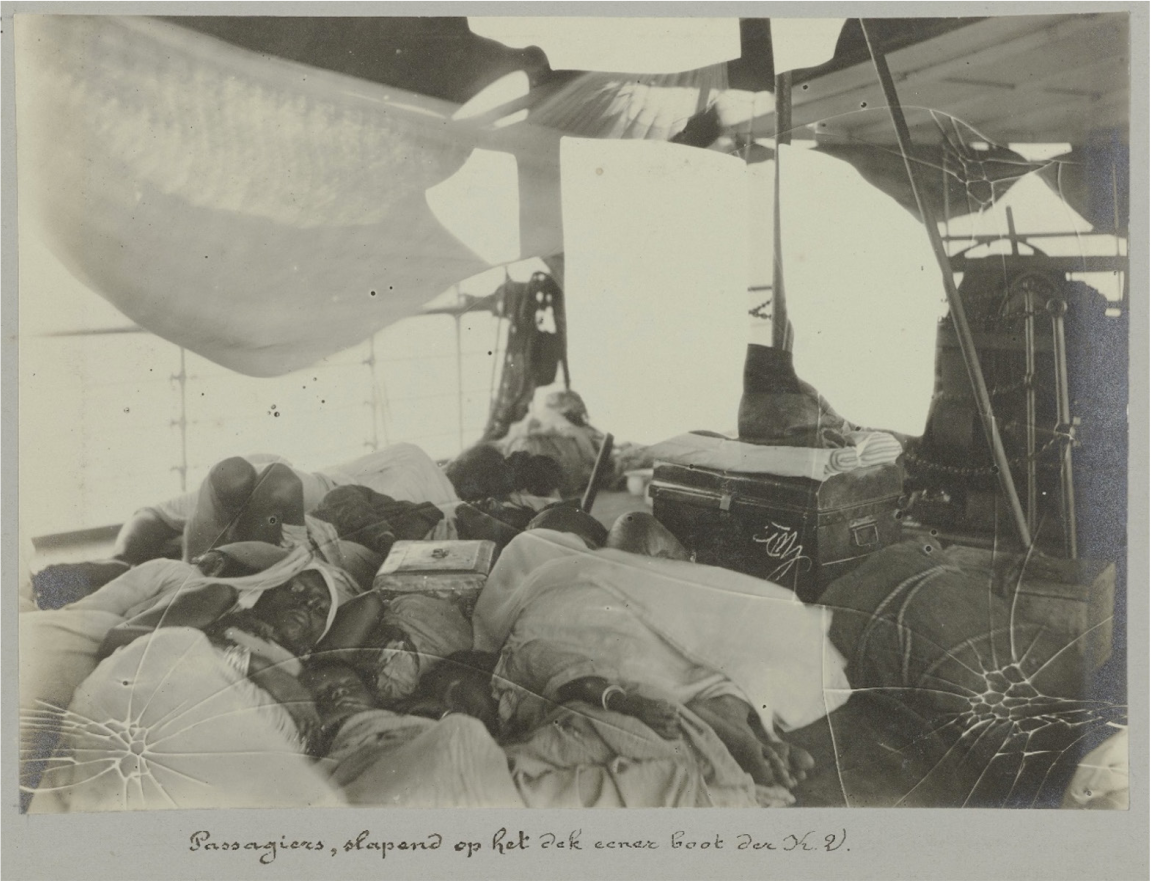

When one closely examines the photograph in Figure 3 the gaze of the Indian female migrant on the left side of the photograph is striking. Her eyes are open and focused on the camera, although her body is positioned as if she is sleeping on the floor of the ship. She seems to be in a resting pose while one of her arms leans on a gathri (cotton bundle of belongings). Her other arm leans on her belly and the bangles (Indian bracelets) that she wears during her ship journey are most probably purchased or given to her before departure in Calcutta. Why is her gaze fixed on the camera and was she for some reason cautious not to be asleep?

Passengers sleeping on the deck of a boat K.V., Gomez Burke (mogelijk), 1891.

Fotoalbum van Suriname 1906–1913. ‘Souvenir de Voyage’, deel 4 (NG-1994-65-4) ontwikkelgelatinezilverdruk, h 120mm × b 167mm. Collection of The Rijksmuseum.

Could she be possibly guarding her children and the jewellery that is kept in the metal box that is placed between the sleeping migrants on the ship? Perhaps she knew about the dangers that a woman could endure during the time spent on a ship. An example is the death of the Indian female migrant Maharani described by Verene Shepherd, who extrapolates on the archival material she collected on Allanshaw, the ship that sailed from India to Guyana in 1885 and which will be discussed further in this article. 6

She looks at the man who is taking her photograph, while at the same time two young children sleep next to her, all cuddled up together in the little space they have on the deck of the ship. The photographer has managed to capture this intimate moment of the sleeping migrants who might at that instant have had their dreams of a better future. An image capturing this extraordinary moment is rarely available in other photographic archives that exist on Indian indentured labourers captured on such voyages. The image is placed in the photographic album named Souvenir de Voyage part 4 and belongs to the collection of the Rijksmuseum (see Figure 4).

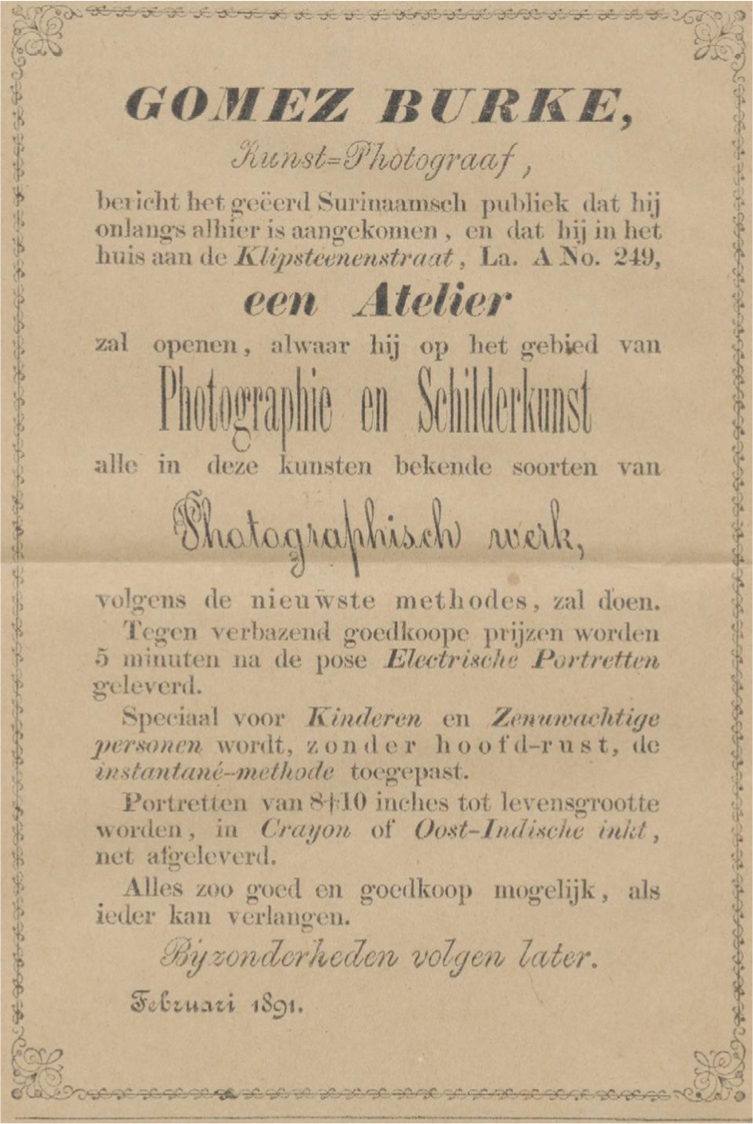

However, it is also questionable as to whether this is a moment in which the space where the woman with her children sleep is being trespassed by an outsider. The man is most probably Gomez Burke, a photographer who temporarily opened his photographic studio in Paramaribo in February 1891, as can be seen in the news article in Figure 5. On the first of July he entered into a partnership with H.A. Siza under the name or the style of Gomez Burke, Siza & Co. Both closed their galleries on the 20th of July and left the colony shortly after this. 7

Fotoalbum van Suriname 1906–1913 ‘Souvenir de Voyage’, deel 4 (NG-1994-65-4) ontwikkelgelatinezilverdruk, h 120mm × b 167mm. Collection of The Rijksmuseum.

Newspaper clipping from Suriname Koloniaal Nieuws en Advertentieblad, Tuesday 16th of February 1891, No. 16.

Vervolgens vergezelde ik de dokter naar het voorruim waar de 285 Javanen zijn gelogeerd. De jonge mannen liggen afgezonderd; de gehuwde paren met de jonge meisjes in dezelfde ruimte. ’T Is interessant hun dobbelen – om rijksdaalders – te zien. Er heerst onder hen veel verkoudheid. Naar de dokter meedeelt is het sterftecijfer op de reis Java-Suriname ongeveer 2% doch had hij tot heden slechts 1 dode, een vermiste en vermoedelijk over boord gesprongen man niet meegerekend. Op de reis Java-Amsterdam werd 1 Javaantje geboren. Thans is de dokter naar zijn hut om te schrijven en ik zit alleen in de rookkamer met de slapende kapitein. (Dagboek Hendrik Doijer, 3 oktober 1903)

[Then I went with the doctor to the front of the ship where 285 Javanese were residing. The young men lie separated; The married couples and the young girls in the same room. It is interesting to see their play with dices for two-and-a-half guilder coins. There is a great deal of cold among them. When the doctor found that the death rate of the Java-Suriname journey was about 2%, but there was only one death so far, a lost man who was suspected to have jumped overboard did not survive. On the journey of Java-Amsterdam there was 1 Javanese new born. Currently the doctor is going to his hut to write and I sit alone in the smoking room with the sleeping captain.] (Translation of the diary of Hendrik Doijer, 3 oktober 1903)

As part of the presentation on Indian female indentured labourers in the Rijksmuseum, the above description of Hendrik Doijer will be combined with the photograph of Gomez Burke. From the diary of Hendrik Doijer it is evident that there is a spatial division on the boats with contract labourers, and although in this case it is the Javanese Indonesian contract labourers that are described, similar situations have been observed in the case of Indian contract labourers.

Several scholars point to the attitude of ignorance with regard to the spatial division on the ship that made movement between compartments possible and, similarly, cases of harassment of women. Anne-Marie Phillips 8 explores identity and governance and points to the spatial divisions on the ship. The separation between single women, couples and single men was described in the Emigration Acts. 9 The segregation was done by general divisions based on gender and marital status. An observation on the spatial division on the ship consists of a description in a circular that came out in 1884 by the Immigration Agent of Guiana. A description is made on the materiality of divisions, ‘two divisions of strong bamboo’ served as a divider on the emigrant vessel. ‘A precedent for this kind of separation could also be found during slavery, where the space below deck was separated into two compartments, one for women and girls and the other for men and boys. Unlike indentured vessels, there was no recognition of family units and marriages on slave ships’ (Phillips, 2014, p. 89). Precautions were taken by the placement of bamboo divisions to restrict the women’s movements. A similar colonial attitude is also part of the policy towards ‘prevention of the spread of venereal disease’ and the protection of single women. In a report written by a Dutch colonial officer called Wiersma, 10 a description of such divisions suggests they were made of wooden lattices and wired netting with a door being closed at night. The materials used for these divisions did not provide substantial protection. One can thus conclude that movement of the opposite gender was possible. Margriet Fokken describes these sorts of divisions as a ‘headshake’, that is not taking the marriage and sexual relationships of the migrants seriously (Fokken, 2018, p. 109).

Oftentimes, as in the case study of Maharani, concealing sexual violence to avoid disrepute became a common medical practice (Phillips, 2014, p. 98). The archival narrative mostly consists of four hundred pages of colonial investigation and correspondence that involves Maharani, an Indian female migrant who passed away on the ship after being raped. One needs to bear in mind that in the colonial mindset the aim of shipping female Indian labourers was to fulfil the sexual needs of the male indentured labourers and establish a permanent labour community. Being aware of this phenomenon in general, colonial officers thought that women who travelled alone, without a male chaperon, were indecent or had an immoral character, as other scholars have suggested (Carter, 1994, p. 3). Due to the testimonies of other female passengers, the commission into this incident could not conclude its investigation with a statement of immoral behaviour by Maharani and needed to investigate further. 11

There is also a trace of a moralizing tendency, as this report also suggests that some of the blame for Maharani’s death is due to the contact between genders – ‘Due to the rough play of cooly women and children’ – insinuating that such play between opposite sexes was indecent and contact between Indian non-family members only pointed to ‘criminal intercourse’, as this was commonly known in India itself. It is clear that the entire strategy was to avoid blame.

The records of female testimonies serve as evidence of the many cases of human errors leading to the question as to whether these sacrifices eventually led to prosperity in the lives of migrant community as a whole in the destination colonies. Besides economic progress that is evident in the later generations, a loss of roots and diffused psychological processes of the migrant status can be found in cultural expressions. A silence or an absence of orally passed down stories of boats must be seen in connection to the suffering that is evident in the colonial documentation of female testimonies.

The photograph shown in Figure 6 does not convey the same feeling of over-staging as that of the migrants represented in Figure 3. We have to bear in mind the different photographers and the aim of visualizing the Indian migrants. One is a Dutch colonizer and the other is a German Herrnhut missionary. This different status, simultaneously with their residence in Surinam, influences the process of visualizing the migrants. German missionaries were already residing in Surinam and familiar with the people and communities there before the indentured labour migration from India took place. The missionaries conducted ethnographic research in Surinam and one of their activities was the production of a large number of photographs of which this is one.

As Bikhu Parekh has noted, ‘The diasporic Hindu was no longer a Hindu happening to live abroad, but one deeply transformed by his diasporic experiences. The Hindu diaspora then contains multiple identities, all sharing some common features but relating them differently and additionally having distinct features of their own.’ 12 The transformation and influence of the migration shaped and transformed the identity of the Indian community that consisted of Hindus and Muslims and is a long continuing process for the different generations, started by a sea journey where people were placed in groups and new relationships were formed. The process of transformation must have started from the emotional grievance and pain of separation from family members and the distance from India.

The photograph in Figure 6 captures a particular migrant group disembarking after a three-month voyage and the different body language gives the first glimpse of expression of this transformation. ‘For most migrants recruited fraudulently, hoping for work in India, the sea voyage was object of fear. While some Hindus believed that crossing the kala pani or black waters would lead to a loss of caste, others, from inland villages, who had never before seen the sea were simply terrified of boarding an ocean-going vessel.’ 13 The faces of the men and women exhibit different expressions but seem to show their emotions quite directly, which have been straightforwardly captured by the photographer. The difference in gender is emphasized in the crouching position of the women with their hands on their knees, while the men are posed standing with their hands positioned alongside their bodies. Additionally, the men have all adopted a serious expression on their faces, forming a unified group. The women, by contrast, have different expressions on their faces that vary from figure to figure. Within the photograph there is a divergence between what appears to be realistic and what is staged.

The women wear saris and cover their heads with orhnis (Surinamese head shawls). Only one young woman or teenager stands up in the photograph and is oddly placed before a man. Remarkably she is the only one who faces the camera and who betrays a look of anxiousness. She is also the only woman who has her hands folded like the man who stands next to her. In a way, in this photograph, she forms a bridge between the two segregated groups of men and women. But this particular woman appears uncomfortable in the position she occupies. Does the position within the photograph symbolize a possible marriage between the man and woman? Compared to her, the older women seem more at ease and all sit on the ground; some with children. She is bedecked with jewellery – has she been picked out by the photographer because of her age and asked to wear all her finery? The Indian clothing and turbans of the men tell us that the photographer wants an ‘exotic’ picture perhaps – but the different styles and colours of the turbans can also tell us additional information about the men – perhaps about their village or regional traditions. Thus, in exoticizing them, the photographer has unwittingly frozen their cultural traits for future generations and helps to humanize the labour migrants pictured here, lifting them from the amorphous streams of ‘coolies’ into individuals with sartorial choices, ethnic belongings, a rich past and a hopeful future.

In Figure 7 it appears as though a couple in a conjugal relationship are posing for the camera. One can see a tropical plant on the left side of the man and dried grass spread on the ground. The gaze of the man is stern and he looks proudly in the direction of the camera while he holds an object in the right hand and a piece of cloth in the left hand. It is not directly clear for which exact purpose the man is holding the objects. Is it a parasol and a handkerchief, protecting him from the sun and to wipe the sweat of his face or purely a decorative object placed in his hand by the photographer?

The position of the female is different, she is placed behind her husband to clarify the hierarchy within the couple. The husband is more important than the wife. She covers herself with the sari so as to not reveal too much of her body. She looks into the camera with a more vulnerable gaze. Her hand is placed on the shoulder of her husband and it is as if she is bracing herself for the gaze of the photographer. Her partner, on the other hand, does not feel the necessity to hold her hand. His appearance appears to be an amalgam of his migrant and ancestral culture. While the trousers and shirt appear to be a sartorial east–west compromise, his headgear refers to his Indian identity and seems to give him a certain dignity that is also reflected in the carefully arranged hair peeking out from the turban and the well-trimmed moustache.

‘Indian women are carefully posed as exotic, domesticated and disciplined objects who seem to accept the control and power of the plantation structure as passively as they sit for the photographer’, writes Joy Mahabir. 14 The way that Mahabir poses the statement reflects the way women were portrayed during the colonial system and this furthermore leads to the question of the possibility of finding different readings within the photographs. Within the hierarchical social structure of the photograph one can find the stereotypical placement of the women behind the men. Nevertheless, the woman in this case is hiding her jewellery with her sari and is thus portrayed as more human than the objectified portrayal of diaspora India women on colonial postcards. Although the jewellery gives a certain ‘reading’ that, according to Mahabir, functions like an ‘alternative Caribbean text’ that gives women an independent status and furthermore offers a feminist reading of Indo-Caribbean culture, the woman here does not feel comfortable showing off the jewellery. Is this feminist reading only possible when one engages with a photograph of a single woman? In the case of this photograph the objectification seems less evident but at the same time the woman does not have an independent status. Does this also tell us that when a woman is portrayed with a man she becomes more human in the eyes of the colonizer? Is the single indentured woman somehow always stigmatized with widowhood and sexual freedom therefore enhanced with a ‘feminist’ status?

Nothing in the picture reveals the Surinam context and the migration process. Thereby the photographer ‘hides’ a certain reality of this migrant couple. The background seems to be a faded landscape with no clear geographical marker, symbolizing the feelings of migrants in whose memory the familiar landscape fades away and is replaced by an unknown space. It is as if the familiar agricultural shapes finally dissolve into the blank page that serves as a metaphor of silence for the past and the suppression of collective memory of the couple and descendants in their future generations in Surinam and the Netherlands.

The background and composition of the photograph in Figure 8 capture a natural feeling without the use of staging, since it is photographed in a village and some of the people in the picture may well live in the house that appears in the background of the photograph. It is interesting to note the figure on the very left-hand side of the photograph, who is just visible in the slightly overexposed edge. Is he watching the people for any purpose? Does he want to merely visit them and see what a Kuli Dorf (coolie village), as stated in the caption of the photograph, looks like? Is his appearance in the photograph accidental, or intentional?

This over-exposed figure of whiteness looks to be well-covered with long trousers – is he a Dutchman posing and aware of the fact that somebody is taking a photograph? He appears to be looking on, rather than to be a subject of the photograph. Of the three figures who are the subjects proper of the photograph, the woman on the right also looks to be an ‘outsider’ to the Kuli Dorf. She appears to be of African origin and is herself observing the couple who may well be the inhabitants of the hut pictured in the centre of the image. Her dress is not typical of Hindu clothing, this, her headwear as well as her physiognomy suggest that she is probably of the Afro-Creole ethnic group. Her pose, looking across at the couple in the guise of an observer, suggests that she is not a resident of the house, but has been placed there as a counterpoint to the ‘coolie couple’ perhaps by the photographer. Her gaze creates a distance between the couple and herself.

The man and woman at the centre of the photograph are presumably the inhabitants of the house. It is difficult to read their facial expressions, but their stance looks quite relaxed. Indeed, there is a slight blurring around the figure of the woman, suggesting that she may have begun to move before the photographer was completely ready with the shot. She is placed in the foreground of the image with the man further behind, something that is quite unusual when one thinks about the position of women and man in society, and the conventional positioning of male and female subjects at this time. The impression given is that the woman feels slightly embarrassed to be standing in front of her husband. You can notice this by her modest position of her hands that she places protectively in front of her chest. Perhaps the photographer has positioned the couple so that the Indian man is in the middle of the composition, with women on his right and left sides. This also places the man standing most directly in front of the hut, as if to say this is my house and I am proud of it. However, the man’s legs do not appear below the knees. Is he standing in a pile of fallen leaves? His incompleteness is disquieting. From a modern perspective, one is tempted to view him as emasculated – his pride in his status as husband and head of household is illusory – he is not complete in his authority because he is subjected to the power of the colonizer and the plantation owner or other employer. His freedom, his mobility is cropped, he is disembodied and cut adrift in an alien society and culture where his ancestral traditions are tolerated at best and where his authority is marginalized.

Visual Traces to Enrich Personal Migration Histories and Art Projects

Observing and analysing the photographic archive at sites like Herrnhut and the Tropenmuseum and the Rijksmuseum are particularly rich and evocative for descendants of the colonial Indian labour diaspora like myself. They bring back memories of visits to the homes of my own maternal ancestors who all came from Surinam and were of Indian diaspora heritage.

I have been active as a researcher and photographer, combining text and image in conceptual installations and performances. In my work I search for traces that are related to my own family history and other times are part of a collective memory. I try to disclose a hidden layered narrative in an urban environment of a neighbourhood or a certain landscape. In my art there is a fascination with history, both of the landscape, the city, the environment and its user. What would unite them, what kind of view is there, on what is it focused? Repetitive elements in my work are photographs of objects and moments that reveal forgotten situations. Objects are functioning as traces. Fragments creating narratives.

These objects and fragments of lives past seem to reveal something as witnesses: an atmosphere, a deed, and the potential interaction between the present and the environment; a view that is presented with a collection of maps, visual and written documents, often poetic and quiet, but always raising questions. My research concerning history and hidden traces has taken me to many places beyond the Netherlands where I was born.

I have found family records and inspiration in archival collections in the United Kingdom, India, Suriname, Mauritius and in Germany, among other sources. Wanting to work with a little-known ethnographic collection containing objects and written documents, I visited the Völkerkundemuseum Herrnhut, which was an almost forgotten and certainly neglected resource. It was not, of course, accidental that I found myself in this relatively obscure region of Saxony searching for a source of inspiration for my project relating to the collective memory of traces from cultural identities in the past. There was and is a link between my family background and the collection of the Völkerkundemuseum Herrnhut and its archives. One of their main collections consists of objects and archival material from Surinam. I started my research with questions concerning the crossover between collective and personal memories of the journeys of the missionaries who inspired and gathered materials for the collection from their time in Surinam compared to my own journeys and family background there.

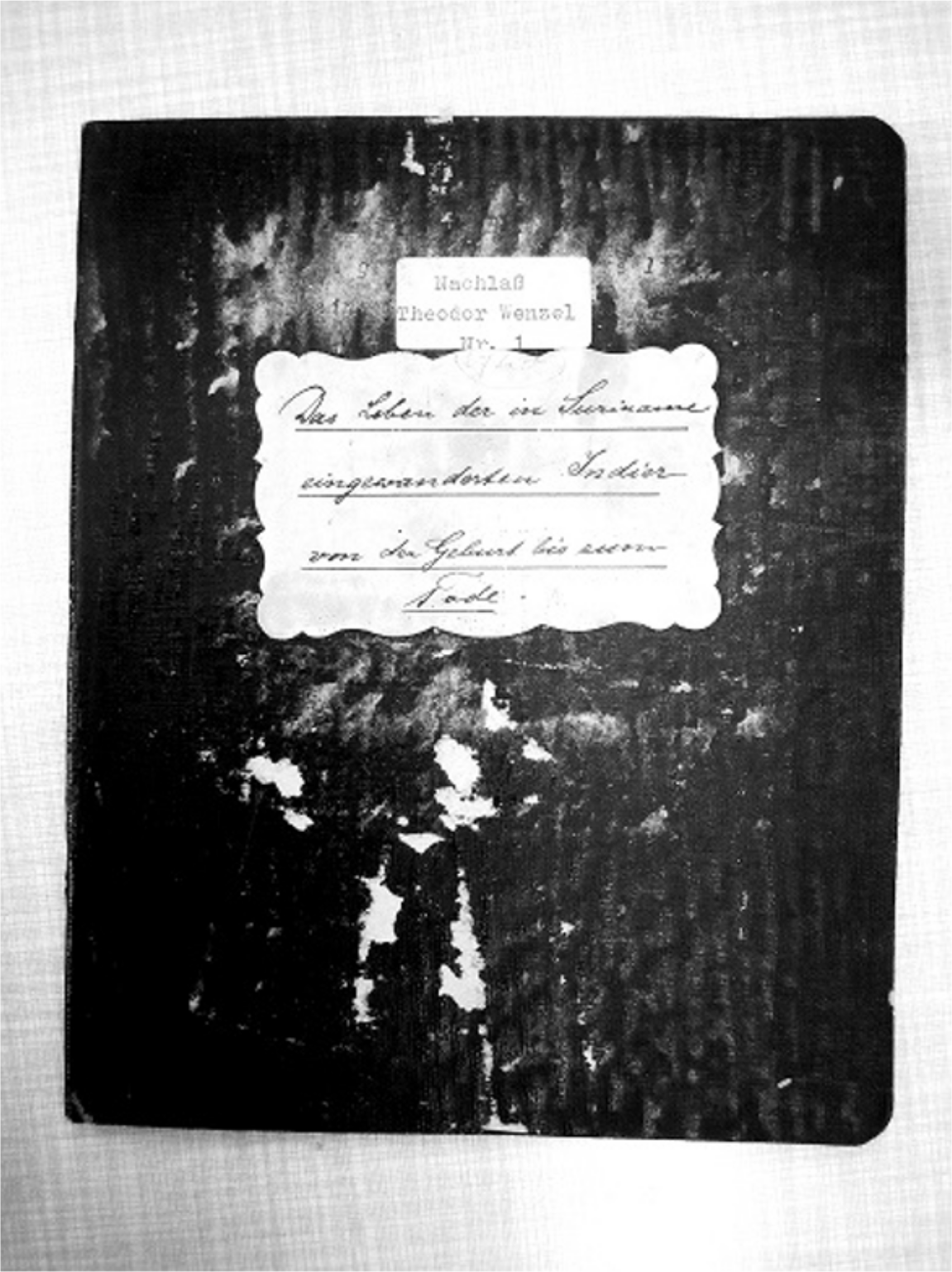

The personal diary of Theodor Wenzel, 1901 (a missionary in Surinam), Das Leben der in Suriname eingewanderten Indier von der Geburt bis zum Tode.

I collected notes and diaries of these missionaries. I tried to discover more personal detailed stories behind the objects and their owners. I found phonetic descriptions from 1901 of Theodor Wenzel (a missionary in Surinam), Das Leben der in Suriname eingewanderten Indier von der Geburt bis zum Tode (Figure 9). In the document, Theodor Wenzel describes the lives of the migrant Indian community in Surinam.

During my observations, the main focus was on the objects of the Surinam–India collection. The origin of these objects cannot be found in the museum. There were no detailed descriptions of who collected the material and who donated it. According to Mr Augustine, curator of the museum, this was done without a clear focus point but purely on the basis of social communication and new meetings with people. As a result of these meetings, objects were collected and given to the missionaries (Figure 10). I acquired scans of the photographs of Indian migrants in Surinam and began working with my imagination. This led to new photographs and text documents produced while researching the collection. The resulting photographs were influenced both by the ‘hidden traces’ in daily life observed in Dresden and the objects of the migrant groups sourced from the collection of the Herrnhut museum. I chose to make a loose open documentation in between the objects and the traces of similar cultural references in daily life in Dresden. Instead of solely focusing on the objects I wanted the collection to come alive. For that reason, I photographed myself holding the objects (Figures 11 and 12).

Reprising the work of Khal Torabully, Veronique Bragard argues, ‘the experience of descendants of indentured labourers from India testifies to a similar limbo consciousness as they are no longer Indians and have to construct new identities for themselves’. 15 The examination and construction of identity are aspects I explore with the self-portraits. A limbo consciousness is expressed by my continuous voyaging between India, Surinam and the Netherlands. On a daily basis in India, I combine Indian clothing with Western and this also feels like a capricious habit. When my daughter Jasvandi Almay Lewis was born in 2021, I made a self-portrait holding the baby wearing a sari that my mother gave me when she visited India (Figure 13). The sari marks the colour of blue that is so vibrant and strong and at the same time reminded me of the blue in the portrayal of Mother Mary that you find in Catholic churches in India. It reminded me of the mixed religions that I was brought up with: Hinduism by my mother, Buddhism by my father and Christianity through my grandparents. This led me to question if my own complex way of identifying with spirituality should be passed on to my daughter.

Through my own researches of photographic collections related to diaspora I have been able to inform and transform the investigation into my own roots and family history. Against the background of this personal narrative arises the larger picture of migration processes and routes between four continents, spanning four generations. It adds a new dimension to the rich shared history and heritage of India, the Netherlands and the former Dutch colonial territories. Further investigation of this photographic history and diaspora heritage combined with the use of personal documentation can contribute to the developing narratives of migration between countries and peoples.