Introduction

Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability mandates that where tertiary education is available, Disabled people should be able to access it on an equal basis to their non-disabled peers. In their systemic review of the research to date on Disabled students in Higher Education, Kutscher and Tuckwiller (2019) state that there are no published studies which assess disability intersectionally and argue that this work should be carried out with some urgency. An examination of the intersection of disability and gender would be a good place to start given the historical and well evidenced disadvantages faced by women students in academia (for example, Phipps and Smith, 2012; Phipps, 2017), and by disabled students in UK HE (Hubble and Bolton, 2020); the higher proportion of women students declaring a disability (Hubble and Bolton, 2020); and the issues women have in getting an official diagnosis (Dusenbery, 2018) which would enable them to “evidence” their disability. The intersection of gender and disability is an important one to explore, and its impacts in Higher Education for students are increasingly important in a context where a university degree is linked to financial security and independence (Leach, 2019).

This paper uses national level data for the UK to examine the relative success of Disabled women students at all degree levels, when compared with non-disabled women, and Disabled and non-Disabled men. It should be noted that this research was entirely carried out before the global Coronavirus pandemic.

This paper will present a brief history of “intersectionality” and set out the arguments around the gendered and abled nature of HEIs and the extant research on Disabled students’ experiences. A chronology is provided at the end of the Introduction which explains the choice to use particular years in some of the analysis. The Method section sets out to describe in as much detail as possible the data used, and provides some international equivalent examples to contextualise the findings outside of the UK. The Findings section is divided into two parts; firstly the data relating to continuation are presented, with sub-sections for each of the continuation categories in the data set. Next the findings in relation to attainment are presented. The discussion is then sub-divided into the findings in relation to continuation, then findings in relation to attainment, and finally conclusions.

A Brief Introduction to Intersectionality

The understandings of structures of power, oppression, and discrimination that are at the heart of intersectionality have a long history in Black Feminism, dating as far back as the anti-slavery movement (for example, Cooper, 1892; Terrell, 1940). This understanding that Black women are multiply-marginalised by race and gender was built upon by Second Wave Black Feminist groups, for example The Combahee River Collective (1977) argued that race-only and gender-only frameworks did not capture the true extent of the social injustices that shape Black Women’s lives. In 1989 Kimberley Crenshaw published her now famous paper which used the term ‘intersectionality’ to capture this understanding of power and oppression (Crenshaw, 1989).

In its early conceptions, then, Intersectionality was a theory to understand and explain how systems of power, oppression, and discrimination can combine in different ways depending on one’s identity (Collins and Bilge, 2016). The core insight of Intersectionality is that “… major axes of social division […] operate not as mutually exclusive entities, but build on each other and work together” (Ibid.: 4). It is the belief that multiply-marginalised individuals experience discrimination and oppression for each of their marginalised identities and that these also combine to create discriminations that are an order of magnitude more pronounced than for each of those marginalisations individually. Collins and Bilge (2016) conceptualise power as being in four domains: interpersonal, disciplinary, cultural, and structural. In the context of this research then, interpersonal power would be related to Disabled women’s experiences with their peers, academic staff, and support staff. Disciplinary power would relate to ideas about who can be conceived as an “expert” or “critical thinker” in UK HE, and how this does not “stick” to Disabled women’s bodies (Ahmed, 2010). Cultural power would relate to the social environment for Disabled women in the UK, to media and government narratives of disability, and the wider cultural discourse around disability in the time period under study. Finally, structural power would refer to the bureaucratic systems with which Disabled women must struggle in order to access UK HE (in relation to disclosure decisions and claiming DSA). Given that students come to university with a variety of different needs and experiences, but also with an expectation of fairness, intersectionality is particularly useful in examining and furthering campus equity (Collins and Bilge, 2016).

Furthermore, Collins (2019) stresses the importance of considering the broader cultural context in which research is taking place when using intersectionality as critical social theory – in the case of the current research this is the broader sexist/hegemonically masculine culture in HE (for example, Acker, 1992; Thornton, 2013), the rise in sexism in wider society as backlash against feminism and gains in equality for women (Phipps, 2017; Bates, 2020), and the hostile environment for disabled people in the UK following the election of the Coalition Government in 2010 (Baillie, 2011; Briant, Watson, and Philo, 2013; United Nations, 2016).

Gendered and Abled Academe

Academe is structured in such a way that it privileges certain men – the wealthy, white, able-bodied man (for example: Acker, 1992; Burkinshaw, 2015). Universities were designed for these men, and the structures still in place make it easier for those who fit this description to succeed. Its systems and practices favour those who fit the archetype of the “rational man” and rewards attributes associated with a certain type of hegemonic masculinity (e.g. Mcdowell, 1990; Thornton, 2013). The “archetypal scholar” values reason over emotion and independence over dependence. There is a long history of the gendered nature of both reason/emotion and independence, with reason and independence being associated with the “male” and emotion and dependence with the “female” (see for example Morgan, 1981; Burkinshaw, 2015). Such observations provide an important insight into the context in which women university students find themselves. In an examination of students’ conceptions of who the “critical thinker” is, Danvers (2018) found gendered notions persist today. She found that for the students in her study, critical thinking was associated with reason over emotion, detachment/objectivity rather than subjectivity and with the male rather than the female. Furthermore, Danvers (2018) found that ideas about who the critical thinker is are tied up with conceptions of “independence”: the critical thinker is someone who has independence of thought and opinion. This centrality of “independence” in forming a concept of the “archetypal scholar” is clear in Leathwood’s (2006) study with students at a university in the UK. Students in her study had internalised this discourse of “independence” as being a central aspect to claiming academic status. The students acknowledged that they expected to need some support in their first year but that the need for support should lessen as they progressed. Furthermore, this belief was also shared by their lecturers, who expected them to be more “independent” and need less support as they progress. Importantly, Leathwood (2006) describes the impact this narrative had on the Disabled students in her study – with those students being apprehensive about asking for support and feeling alienated by the ideal of the “independent learner”.

This conception of the “archetypal scholar” acts to exclude women through the gendered nature of reason/emotion; and excludes Disabled people through the pathologising of dependency. Disabled women, then, experience a compounded problem of claiming academic status. This “intersectionality” (Crenshaw, 1989) of disability and gender in HE warrants investigation. Using intersectionality as theory allows an examination of the power structures at play in UK HE for Disabled women (Collins and Bilge, 2016). As Collins (2019: 28) argues, whilst structural phenomena (for example Ableism and Sexism) can be conceptualised as distinctive, “examining them from where they intersect provides new angles of vision of each system of power as well as how they cross and diverge from one another”.

Disability in Higher Education

There is a plethora of research examining Disabled students’ experiences across the Global North. This research examines such things as the stigma and discrimination they experience from their peers and staff (Cole and Cawthon, 2015; Grimes et al., 2019; Osborne, 2019); the additional labour of Disabled students (Hannam-Swain, 2018; Osborne, 2019); the necessity of “good” disability support for Disabled students’ success (Goode, 2007; Madriaga et al., 2010); their progression and continuation through courses (Mullins and Preyde, 2013; Francis et al., 2019; Kutscher and Tuckwiller, 2019); and their attainment (Richardson and Wydell, 2003; Richardson, 2009; Osborne, 2019).

Disabled students’ experience of stigma and resentment from their peers and staff mean that Disabled students feel like they do not “belong” or are “too much trouble” (Luna, 2009; Mullins and Preyde, 2013; Francis et al., 2019). This, compounded by campuses, buildings, and classrooms that are not accessible, creates an environment that can be hostile to Disabled students, such that Hector et al. (2020) found Disabled students drop out at higher rates than their non-disabled peers. For those Disabled students who do complete their course, much of the literature shows that they achieve on a par with their non-disabled peers (Richardson and Wydell, 2003; Richardson, 2009; Osborne, 2019). However, Hector et al. (2020) present evidence of a gap between Disabled and non-disabled students of around 3% in the attainment of “good honors”. This gap can be linked to the finding that disability-specific support is essential for Disabled students’ achievement (Richardson and Wydell, 2003; Goode, 2007), and would thus suggest that support for Disabled students in the UK is currently not effectively ensuring Disabled students’ success. Madriaga et al. (2011: 901) conclude: “… the evidence […] shows that disabled students who do not receive institutional disability support under-perform”. Hector et al. (2020) also report the low uptake of Disabled Students Allowance (DSA, discussed below) in the UK, and describe the many difficulties Disabled students have in accessing HE. As a consequence Hector et al. (2020: 6) state “… our evidence demonstrates an unhappy situation for many disabled students”.

Declaring a disability at a UK Higher Education Institution (HEI) allows Disabled students to access a variety of support. UK HEIs have a legal duty ( Equality Act, 2010) to ensure that Disabled students get “reasonable adjustments” to facilitate their access to learning, and this is usually managed by a disability/learning support department (Hubble and Bolton, 2020). This department has the responsibility of helping each Disabled student create a plan of adjustments that will support their learning; and disseminating this to the students’ teaching team. Furthermore, in the UK Disabled students have access to the DSA. This funding is not means tested, and is non-repayable; it can be used to pay for equipment (for instance, laptop, equipment to audio record lectures), to pay for non-medical support (such as note takers), and for other additional costs incurred due to the student’s disability (such as paying for printing of learning materials). To access this support though, a Disabled student must disclose their disability to the institution, and provide “evidence” of their diagnosis and how their condition impacts them.

The benefits of disclosing a disability in the UK, then, are significant. Francis et al. (2019) found that for some Disabled students, disclosing their disability to their HEI was empowering. Participants in their study described finding a “community” of Disabled students on their campus, and feeling less isolated. Students also felt that accepting the label “Disabled” validated their difficulties and made them feel less like they were “lazy” or “not trying hard enough” (Francis et al., 2019; Osborne, 2019). In a systematic review of the research on disability in HE, Kutscher and Tuckwiller (2019) also found that disability-specific social support was important for Disabled students’ success in HE. Considering that specific adjustments for disability are essential to Disabled students’ success (Goode, 2007; Madriaga et al., 2010), the benefit of disclosing to a HEI becomes about being able to progress through a course and graduate with a degree, on a par with their non-disabled peers. Put another way, the cost of non-disclosure is potentially dropping out or under-performing. However, there are also costs to disclosing: Applying for “reasonable adjustments” through an institution and/or DSA requires navigating a complex bureaucratic system and lots of additional labour (Riddell and Weedon, 2013; Hannam-Swain, 2018); and having adjustments in place can make the student’s disability more “visible” and so opens them up to microaggressions and stigmatisation (Goode, 2007; Madriaga et al., 2011; Osborne, 2019).

Stigmatisation

The extant literature demonstrates that Disabled students face many kinds of discrimination and stigma in HE across the Global North. Research in the US and Canada has shown that Disabled students have experienced negative attitudes to their disability or to disability in general from their peers, academic staff, and support staff, even to the extent that accommodations have been refused by academic staff (Mullins and Preyde, 2013; Cole and Cawthon, 2015; Grimes et al., 2017, 2019). It should be noted that many academic staff feel ill-prepared by their institutions to support Disabled students. Svendby (2020) found that staff were provided with very little training, and given very little support in making their teaching more accessible. Any failure in support for Disabled students in the UK should be viewed as an institutional problem and not the responsibility of individual academic staff.

In the UK Vickerman and Blundell (2010) found that participants worried that disclosing their disability to their institution would mean that they would not be offered a place on their chosen course; and Osborne (2019) found that fears of stigmatisation and negative attitudes meant that many of her participants were also reluctant to disclose their disability. There are also examples in the literature of staff and peers resenting Disabled students because they feel that accommodations are “unfair” or “undeserved” (Richardson and Wydell, 2003; Bê, 2019; Grimes et al., 2019). So, for example, a participant at a university in England described how her peers felt that she was not committed enough to her course because of her sporadic attendance; that she did not really “deserve” the support and questioned whether her disability was “real” (Bê, 2019). Again, better institutional support and training for academic staff would help alleviate some of these issues.

Research shows that Disabled students worry about being perceived as “lazy”, “fakers”, or “malingerers” by their peers and academic staff (Osborne, 2019; Grimes et al., 2019). These feelings of being perceived as “faking” are compounded by the need for “evidence”. Students in UK HEIs need to provide official documentation in order to get support (from their institutions and to claim DSA): Osborne (2019) argues that HEIs have no understanding of the difficulties involved in getting a diagnosis; how this is impacted by “race”, gender, socio-economic class, and so forth (Dusenbery, 2018), and that this need to provide evidence is a form of gate-keeping that acts to make access to HE more difficult for Disabled people in the UK.

Disabled Students’ Additional Labour

Disabled students perform additional labour in various forms whilst they are studying: First, there is the additional labour of having a disability/impairment. Managing a condition, attending medical appointments, and so forth are additional labour that non-disabled students do not have to perform (Hannam-Swain, 2018; Osborne, 2019; Hector et al., 2020). On top of this, HEIs expect additional labour from Disabled students through the bureaucratic processes involved in accessing adjustments and in ensuring that adjustments are provided as they should be by all academic staff. Several studies in the UK have demonstrated that the process for applying for DSA is lengthy and time-consuming (Riddell and Weedon, 2013; Hannam-Swain, 2018; Hector et al., 2020). Furthermore, Disabled students need to perform extra labour in managing the previously discussed stigmatisation they can face from their peers and staff. Disabled students are then forced to spend additional mental and emotional labour in “justifying” their need for support and in managing the negative perceptions of the non-disabled people around them.

Thus, for Disabled students there is a constant need for “self-advocacy” to ensure that they receive adjustments, to navigate through the bureaucracy, to manage staff and peers’ perceptions, and so on. Osborne (2019) highlights the problem with “self-advocacy” arguing that this model allows HEIs to shift responsibility for Disabled students’ access from the institution to the individual Disabled student. Providing equal access becomes about Disabled students’ ability to self-advocate, rather than an institutional responsibility. The need to self-advocate for access/adjustments also becomes a double-bind for Disabled students: Disabled students must self-advocate in order to ensure they get access, but that same self-advocacy is then used as evidence that they do not really need the support they are fighting for (Hannam-Swain, 2018; Osborne, 2019). Disabled students, then, are forced to perform a level of disability that justifies their adjustments, whilst also needing to perform sophisticated self-advocacy to get those adjustments. For many Disabled students this becomes exhausting, with a participant in Francis et al.’s (2019: 294) research stating: “I know if I don’t advocate for myself nobody else will. That’s the reality, right?”; and a participant in Osborne (2019: 245) noting that: “Repetitive and ongoing self-advocacy is exhausting!”

For Disabled women students in UK HE, diagnosis (and access to evidence and thus support) is hindered by medical sexism (Dusenbery, 2018). Self-advocacy becomes more important and more difficult as women’s assertiveness is more likely to be perceived as inappropriate, and medical stereotypes mean that women are often assumed to be lying or exaggerating their medical conditions (Dusenbery, 2018). And as women students they face an increasingly hostile environment of misogyny on UK university campuses from their male peers (Phipps and Smith, 2012; Phipps and Young, 2015; Bates, 2020).

Chronology

The chronology of the research covers a period of substantial change in UK HE funding generally, and for Disabled students in particular. In 2010 the UK Government changed the funding model of HE, so that students became responsible for the full cost of tuition fees for their undergraduate degree. These changes came into force for the 2011/12 academic year. Students who started an undergraduate degree in 2010/11 were paying just over £3000 per year for tuition fees. Those students who started in 2011/12 (and all since) were paying up to £9000 a year. In 2014 the government announced changes to DSA, in an effort to reduce costs (Willets, 2014, cited in Lewthwaite, 2014). These changes put pressure on HEIs to “mainstream” disability access measures.

The proposal was extensively covered in the UK press, with the National Union of Students and disability rights charities condemning the changes (Lethwaite, 2014; Morgan, 2014; Payne, 2014; Pring, 2014; Swain, 2014). The changes meant a reduction in the funding from the DSA, and Disabled students now had to navigate both the DSA bureaucracy and their HEIs systems to get full disability support. In 2016 the UK Government introduced a postgraduate loan scheme that mirrored the undergraduate funding model. Initially, these new loans only provided funding for Master’s level study, but by 2017/18 had been extended to include Ph.D. study. These loans provided funding for students to pay fees and have a small amount of money left over for living expenses. The loans are only repayable upon graduation and once the student is earning above a certain threshold.

These observations suggest that Disabled women students could face significant intersectional barriers in succeeding in HE in the UK. Using national level data to assess their progression through their courses and their attainment (at the undergraduate level), this research examines whether Disabled women can be considered as being successful (or not) in HE there.

Method

This paper is taken from a larger exploratory study (Meadows-Haworth, 2020), aiming to assess if there is evidence of intersectional disadvantage for Disabled women students (at all degree levels) in UK Higher Education. It uses descriptive statistics drawn from publicly available data to examine the “success” of Disabled women, when compared with Disabled men, and non-disabled men and women. The data is from two sources: AdvanceHE and The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). In both data sets, “Disability status” is a self-reported measure; students can identify as Disabled “′if they have a physical or mental impairment, and the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on his or her ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities” (Equality Act, 2010).

AdvanceHE

AdvanceHE is a non-government oversight body, which established two “awards” aiming to improve gender and racial equality in HEIs. They produce annual data sets that HEIs can use in benchmarking for their award applications. The data used in this study are the student data from academic years from 2012/13 to 2017/18. The data provided in Advance HE reports is rounded in line with HESA data protection policy. This means that all the numbers are rounded to the nearest 5.

HESA Data Set

The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) is the body that oversees and monitors statistics for HE staff and students in the UK. HEIs must send in annual data to HESA for all of their staff and students, and HESA makes this data available for others to use. The HESA data is a comprehensive set of data for all students registered with a UK HEI. HESA publish some of this data on their website, and researchers/students can request customised data sets for a fee. Due to cost constraints for the current research, a small sample of three years’ worth of data was requested, limited to eight variables. The HESA data set, therefore, consists of student data for academic years 12/13, 14/15, and 17/18.

Success and Attainment

To compare the “success” of Disabled women students, two outcome measures were used: “continuation category” and “attainment”. Continuation category data measures students’ progression through a degree course for students on undergraduate and postgraduate taught degrees. Students are classified as either: “continuing at institution” if they are progressing onto the next year of their degree; “gained intended award” if they graduate from their degree course (i.e. an undergraduate student graduating with a Bachelor’s degree, a Masters student graduating with a Master’s degree); “gained other award” if they leave their course early but have accrued enough learning credits for a lower award, for example a student on a Master’s degree who leaves with a postgraduate certificate (equivalent to one third of a Masters (Smith, 2020)); “dormant” if the student has suspended their studies for any reason, i.e. they have taken a period of leave from their degree course; and “left no award” if, for example, they leave their course without completing enough learning credits for an award or there is no lower award to offer. Table 1 shows the degree level labels used in the data sets, along with descriptions of each.

Attainment data provides the degree classification of undergraduate students on completion of their course. Students in the UK usually receive one of four classifications if they pass their course, based on their academic grades: First Class Honours, Upper-Second Class Honours, Lower-Second Class Honours, and Third Class Honours. Table 2 shows some examples of international equivalence.

In the UK, a common definition of “success” in HE is considered to be the attainment of “Good Honours”, i.e. graduating with a First Class or Upper-Second Class Honours degree.

Examining the rates of continuation, award, dormancy, or drop-out for Disabled women when compared to their peers allows an exploration of whether Disabled women are being discouraged and disadvantaged through the course of their studies.

An examination of Disabled women’s attainment in comparison to their peers has not been carried out previously. Hector et al. (2020) have identified an attainment gap for Disabled students, but as yet no-one has examined this intersectionally. Sex/Gender could act as a protective factor here for Disabled women, since women tend to out-perform men (Phipps, 2017); but the literature also suggests that Disabled students who are not properly supported under-perform in comparison with their peers (Richardson and Wydell, 2003; Goode, 2007; Madriaga et al., 2011). It is therefore imperative that some examination of the attainment of Disabled women is undertaken.

Findings

The research focuses upon the proportions of students in a four-student typology (Disabled women, Disabled men, non-disabled women, non-disabled men) in order to account for any differences in the population sizes of Disabled vs non-disabled students. If these proportions change in a similar fashion then it would indicate no effect of disability. A difference in any changes in proportions would indicate the possibility of an effect of disability status. The analysis is focused upon only full-time students. The rationale for the years chosen is provided in the chronology section in the Introduction.

Continuation Category Data

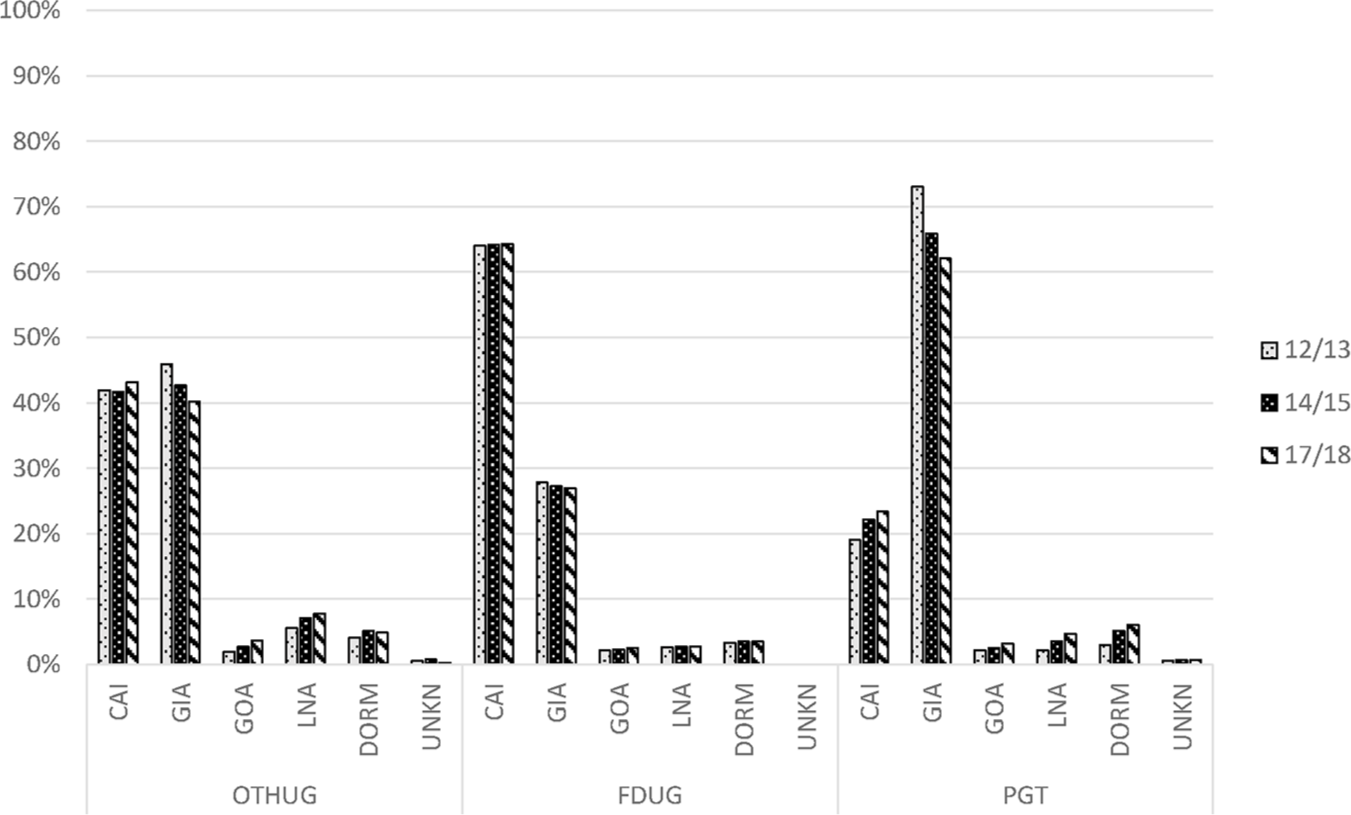

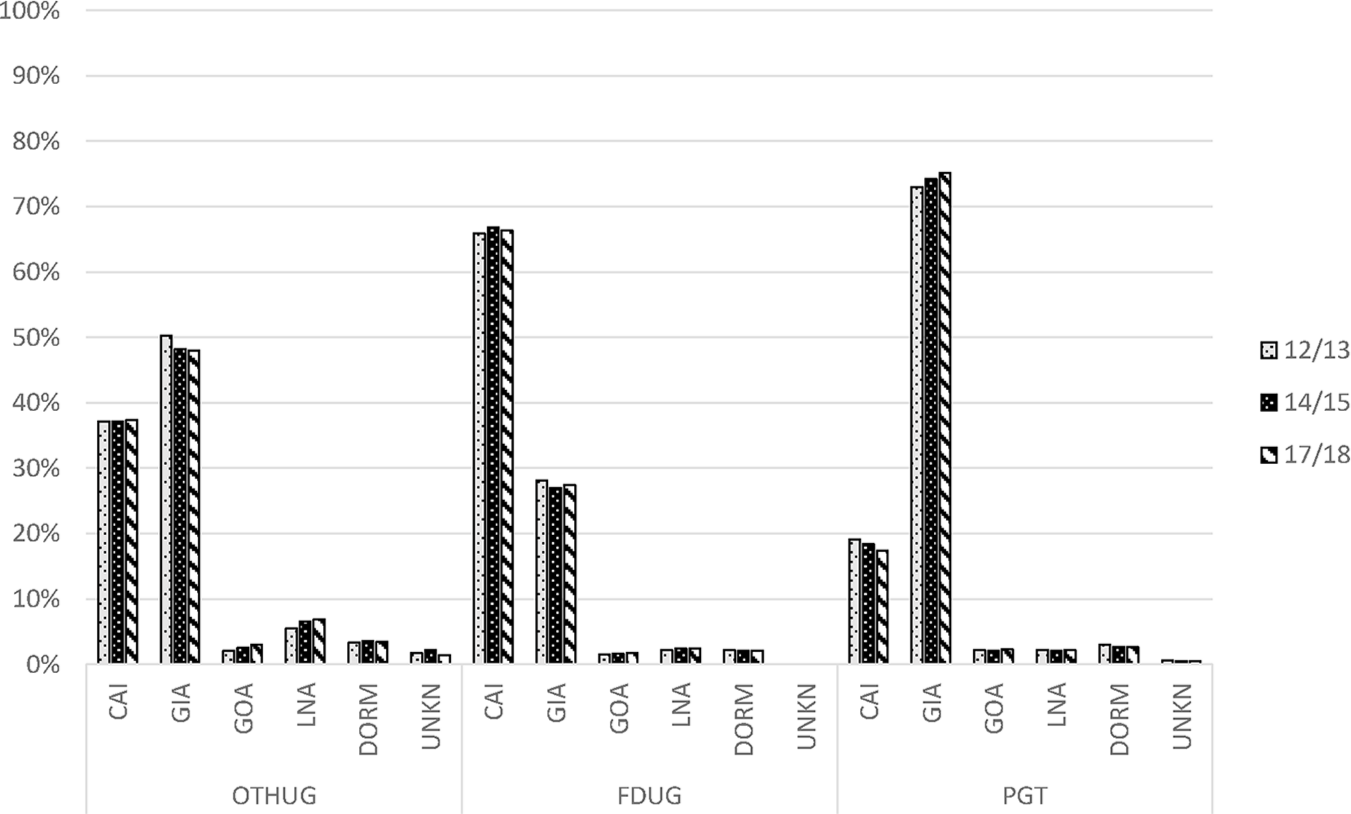

To assess whether there are intersectional effects of disability and gender on continuation, I used the HESA data set to calculate the proportions of each student group in each continuation category, at each degree level. The HESA data records students as “continuing at institution”, “gained intended award”, “gained other award”, “dormant” or “left no award”. Due to the way the data is constructed by HESA it is not possible to do this for Postgraduate Research students, so the focus is upon undergraduate and Postgraduate-Taught students. Figures 1 to 4 show the proportion of each group of students in each of the continuation categories for those on other-undergraduate, first-degree undergraduate or postgraduate-taught courses.

I. Continued at Institution (CAI)

Figure 1 shows that for all three years, at other-undergraduate level just over 40%, for first-degree undergraduate 60–65%, and for postgraduate-taught around 20% of Disabled women continued at their institution. For postgraduate-taught level a lower proportion of students continuing at their institution is to be expected, since most full-time Master’s courses are one year; therefore, a higher proportion of these students should be in the “gained award” categories. The number of Disabled women continuing at first-degree undergraduate level is also about what would be expected; degree courses are typically three years, so at any time there should be around two-thirds of these students continuing. For other-undergraduate students it is difficult to estimate a proportion that should be continuing, due to the wide variety of courses under this heading. Therefore, the best way to judge whether there is an effect of disability/gender for these students is to compare these proportions for Disabled women with rates of continuing other-undergraduate non-disabled women, Disabled men, and non-disabled men.

The proportion of disabled women in each continuation category, by level for the 12/13, 14/15, and 17/18 academic years

There is a lower proportion of non-disabled women (Figure 2) who continued at their institution at other-undergraduate level, hinting that there is perhaps an effect of disability here for these students, such that a higher proportion of Disabled women are continuing than of non-disabled women. The proportions of non-disabled women continuing at both first-degree undergraduate and postgraduate-taught level are similar to the proportions of Disabled women.

The proportion of non-disabled women in each continuation category, by level for the 12/13, 14/15, and 17/18 academic years

For Disabled men (Figure 3) the proportion of students continuing is around 45% at other-undergraduate, 65% at first-degree undergraduate and around 20% at postgraduate-taught level. So, a higher proportion of Disabled men than either group of women continued at their institution at other-undergraduate level. For non-disabled men (Figure 4) the proportion of students continuing is around 40% at other-undergraduate, around 65% at first-degree undergraduate and 20% at postgraduate-taught level.

Ii. Gained Intended Award (GIA)

Looking at the data for the next category, Figure 1 shows that for Disabled women around 30% of first-degree undergraduates gained their intended award across all three years. This proportion is about what would be expected, with one-third of students leaving a three-year degree course with their intended award. For other-undergraduates, there is a drop in the proportion of Disabled women gaining the intended award, from 46% in 12/13 to 40% in 17/18. This change in the proportion of Disabled women cannot be totally accounted for by the rise in Disabled women continuing at their institution.

For postgraduate-taught students, there is a decline over time in the proportion of Disabled women gaining the intended award, from just over 70% in 12/13 to just over 65% in 14/15, and just over 60% in 17/18. Since there are no changes for Disabled women students in the continued at institution category, it is important to determine which of the other continuation categories increase to account for the drop in Disabled women at postgraduate-taught level gaining their intended award – are these students leaving with a different award, leaving without an award, or dormant?

For non-disabled women (Figure 2) around 50% of other-undergraduates, just under 30% of first-degree undergraduates and just over 70% of postgraduate-taught are gaining the intended award. There is no change in these proportions at other-undergraduate or first-degree undergraduate level over time, but there is a slight increase in the proportion of non-disabled women gaining their intended award from 12/13 to 17/18. Therefore, the decline in the proportion of Disabled women who gained the intended award at postgraduate-taught level is not a simple gender effect. In order to assess whether this is an effect of disability or of the disability/gender intersection it is necessary to examine the data for Disabled and non-disabled men.

The data for Disabled men (Figure 3) shows just over 35% of other-under-graduates, around 25% of first-degree undergraduates, and just over 60% of postgraduate-taught students gained the intended award. The data for non-disabled men (Figure 4) show a slight increase in the proportion who gained the intended award at other-undergraduate level from 12/13 to 17/18. At first-degree undergraduate level the proportion remains at around 25% for all three years. At postgraduate-taught level around 70% gained the intended award across all three years. This would imply then that there is an intersectional effect of gender/disability at postgraduate-taught level for the gained intended award category – with a decreasing proportion of Disabled women gaining their intended award, a pattern that is not evident for non-disabled women nor Disabled men.

Iii. Gained Other Award (GOA)

Figure 1 shows that for Disabled women there is a doubling in the proportion gaining a different than intended award: from around 2% at all levels in 12/13 to around 4% at all levels in 17/18. For Disabled men (Figure 2), there is an increase from around 3% at all levels in 12/13 and 14/15 to 4% in 17/18. For non-disabled women (Figure 3), the proportion of students leaving university with a different than intended award is around 2% for all levels, across all three years. Finally, for non-disabled men (Figure 4), there is no change in the proportions over time, but there are differences by level: at first-degree undergraduate level 2% of students left with a different than intended award, 3% at other-undergraduate and 4% at postgraduate-taught level.

Iv. Left No Award (LNA)

Looking at the data for the proportions of students who left without an award, Figure 1 shows that for Disabled women there is an increase in the proportion of students at other-undergraduate level leaving their course without an award, from 4% in 12/13 to 8% in 17/18. At first-degree undergraduate level the proportion of Disabled women in this category remains at the low level of 3% across the three years. At postgraduate-taught level, there is an increase in the proportion of Disabled women in this category from 2% in 12/13 to 5% in 17/18. For Disabled men (Figure 2) at other-undergraduate level, there is an increase in this category from 5% in 12/13 to 10% in 14/15 and 17/18. The proportion of Disabled men remains stable across the three years, at 3% for first-degree undergraduate and 4% for postgraduate-taught level. For non-disabled women (Figure 3), the proportion of students leaving university without an award at other-undergraduate level increases from 3% in 12/13 to 7% in 17/18, proportions of non-disabled women at first-degree undergraduate and postgraduate-taught level remain stable at around 2% for all three years. For non-disabled men (Figure 4) the proportions of students leaving without an award is around 3% at first-degree undergraduate and postgraduate-taught level, at other-undergraduate level there is an increase in the proportion of non-disabled men leaving without an award from 8% to 11%.

V. Dormant (DORM)

The data for the proportions of students who are dormant in each academic year shows that for Disabled women at first-degree undergraduate and postgraduate-taught level, there is a slight increase from just under 5% in 12/13 to 5% in 17/18. At other-undergraduate level there is an increase in the proportion of students who are dormant, from under 5% in 2012/13 to around 8% in 17/18. The proportion of students who are dormant remains stable for all levels for all three years, at around 5% for Disabled men; around 3% for non-disabled women; and around 4% for non-disabled men. There are slight fluctuations for the non-disabled men at other-undergraduate level, with a slight drop from 5% in 12/13 to 4% in 14/15 and 17/18.

Attainment Data

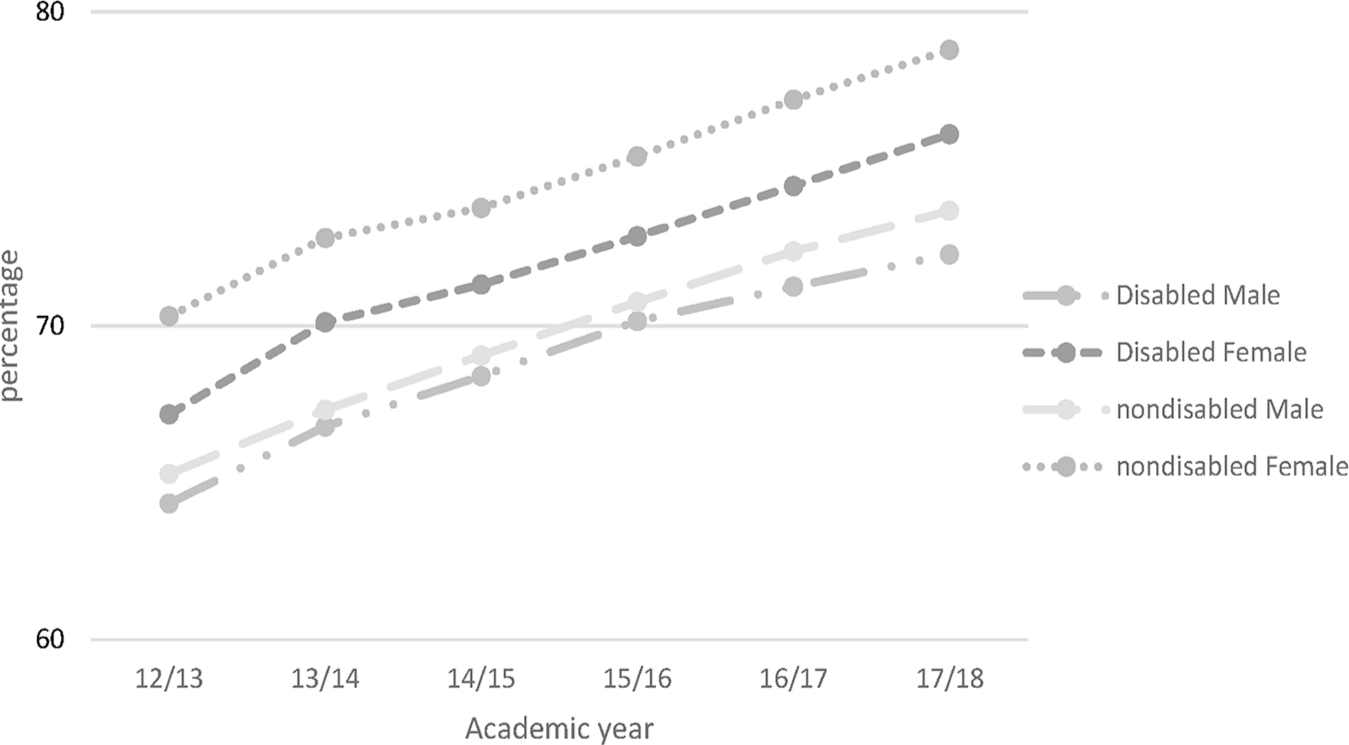

In order to answer the question about how “attainment” may be impacted by gender, disability, and the gender/disability intersection, I used the AdvanceHE data to examine the proportions of students who attained a “Good Honours” degree. Figure 5 shows the proportion of each student type that attained Good Honours from 2012/13 to 17/18.

Proportions of students who attained “Good Honours” by Disability status and gender over time

iPlease note the y-axis is truncated to between 60% and 80% in order to make differences more visible

The data in Figure 5 show that in all student groups the proportion of students attaining “Good Honours” is increasing each year, and following much the same pattern. Non-disabled women have the highest proportion attaining Good Honours, followed by Disabled women, then non-disabled men, and finally Disabled men. This would seem to suggest that there are separate effects of gender and disability, such that a lower proportion of Disabled students attain Good Honours than non-disabled students; and a lower proportion of men attain Good Honours than women (within disability status). It does not appear that the changes to DSA have had an impact on disabled students in terms of their attainment.

Discussion

Continuation Category

When examining the continuation data, the most concerning aspect is the finding that HESA do not have any progression data for postgraduate research students. Given HESA’s central role in the monitoring of equality in UK HEIs, this is worrying. Using HESA data it is not possible to assess the proportions of students who complete their postgraduate research courses, notwithstanding to see if there are any differences in the completion rates for minoritised students. UK research councils do hold some completion data for PGRs, but this is only for the very small proportion of students funded through a research council grant, and the numbers of Disabled students being awarded grants are so low that intersectional analysis would not be possible. In the 2019/20 academic year only 8% of UKRI PGR funding awardees were Disabled (UKRI, 2021).

One factor that has a significant impact on the continuation/graduation of Disabled students is that of “self-advocacy”. As discussed above, the need to self-advocate places an additional burden on Disabled students, and can act to discourage them from continuing in their studies (Osborne, 2019; Hannam-Swain, 2018). Compounding this, being Disabled is, in itself, an additional labour (Hannam-Swain, 2018; Osborne, 2019). Disabled students perform a lot of labour to manage their impairments/conditions, attend medical appointments, manage medications, and so on. Being Disabled can be, in and of itself, a full-time occupation. Before they even begin to do the labour needed for their chosen courses, Disabled students may already be performing a large amount of work. Add on top of this the labour needed to make a DSA claim, and the constant need to self-advocate, and it is not surprising that fewer Disabled students complete/graduate from their chosen courses. The data findings from my study suggest that these factors have differential impact at different degree levels, with postgraduate-taught level seemingly where these factors most impact Disabled women. There is a plethora of research examining the attrition rates of Disabled students at the transition points of moving from Bachelors to Masters level study, and again at the transition to Ph.D. (Osborne, 2019; Hector et al., 2020; Hubble and Bolton, 2020). This study demonstrates that even when Disabled women students make the transition to Master’s level study, they are often not completing those courses.

That being said, there seems to be no differences in continuation for first-degree undergraduate students, meaning that for these students at least, there are protective factors in place which ensure that Disabled students continue or graduate at a similar rate as their non-disabled peers. In their systemic review of the literature, Kutscher and Tuckwiller (2019) found several factors that increase graduation and success rates for Disabled students, including appropriate and good quality disability-specific accommodations; well trained and understanding staff; family and/or other off-campus support; positive peer interactions; and belonging to a Disabled community on campus. The right kind of accommodations being essential to Disabled students’ persistence and success at university is a theme throughout the literature (Bê, 2019; Francis et al., 2019; Goode, 2007). It would seem from the data examined in this study that, at least at first-degree undergraduate level, UK HEIs are managing to provide these things. At the postgraduate-taught level though, this system seems to break down for Disabled women. It also appears that the changes made to DSA may have had an impact, since many of the changes in continuation of Disabled students only happen following the proposal of changes to DSA in 2014.

The findings suggest that there were some intersectional impacts of gender and disability present for postgraduate-taught students. For Disabled women in UK HEIs, there is a second set of discriminations that must be negotiated – those in relation to sexism. A plethora of studies has demonstrated that UK HEIs are systemically sexist organisations (for example Acker, 1990; Bagilhole and Goode, 2001; Thornton, 2013). Although much of the research has been on the impacts of sexism on academic staff, this culture feeds into how students view themselves and are treated by their peers (Danvers, 2018). Concepts such as the “reason/emotion” dichotomy, ideas about the value of “independence” and ideas about the “archetypal scholar” frame students’ understandings of themselves and those around them (Leathwood, 2006; Danvers, 2018). Research with student populations also shows a growing epidemic of sexual harassment and violence against women on university campuses, and can be linked to the rise of extremist misogynistic content in online spaces (Bates, 2019). Again, this has been acknowledged as a problem by UK academia, and in 2016 Universities UK published guidance for HEIs on how to begin to tackle this problem (Universities UK, 2016). The data presented here provide some hints at the intersectional nature of disadvantage that can be faced by Disabled women students, in the higher proportion of Disabled women students leaving their postgraduate-taught courses without an award. At this point it would be irresponsible to speculate as to the reasons why this disparity exists; the data presented here, however, demonstrate that this is an area that needs further research.

Attainment

In the data focused upon here there is an effect of gender on attainment, with women out-performing men (within disability status). This finding is not surprising since much of the literature shows that girls do better than boys throughout compulsory education (Phipps, 2017). In Richardson’s (2009) examination of the attainment of “Good Honours”, he found that gender was a significant factor in explaining the variance in performance, with women being more likely to attain Good Honours.

The differences in the performance of Disabled students shown in the AdvanceHE data contradict the general findings in the literature that Disabled students earn “Good Honours” at the same rate as their non-disabled peers (for example Richardson, 2009; Osborne, 2019). Richardson and Wydell (2003) found that the only differences in attainment in their study sample were between non-disabled students and Disabled students without adjustments. Madriaga et al. (2011) also demonstrate the necessity of accommodations for Disabled students, concluding that “… the evidence also shows that disabled students who do not receive institutional disability support under-perform” (901). Hector et al. (2020) report that take-up of DSA is very low, meaning many Disabled UK students are not getting comprehensive support and accommodations.

Another reason for the differences in the performance of Disabled and non-disabled students in this study could be due to extraneous variables not accounted for. Richardson (2009), in a study of all UK students awarded “first degrees” in 2004/05, found that disability status alone explained only 0.1% of the variance in attainment; the differences in Disabled and non-disabled students’ attainment were accounted for by factors such as grades on entry, subject studied, age, gender, and mode of study.

Conclusion

It is important to note that the findings presented here are preliminary in nature; further research is planned which will examine Disabled students’ success in more depth and using more sophisticated statistical techniques. Therefore, conclusions about the findings should be drawn cautiously. There are many other factors not examined within the data presented here; for example, disclosure choices (Lynch and Gussel, 1996; Richardson and Wydell, 2003; Cole and Cawthon, 2015; Osborne, 2019), rates (Grimes et al., 2017), how these have increased in recent years (Hubble and Bolton, 2020), and gender differences in these (women are more likely to disclose than men) (Hubble and Bolton, 2020); and reasons for non-disclosure and the links to student self-identity (Mullins and Preyde, 2013; Grimes et al., 2017; Lister, Coughlan, and Owen, 2020).

The research I have presented here is the first to examine the intersection of gender and disability in UK higher education. It shows that there are areas where there appears to be an intersectional effect of gender and disability, such that Disabled women are experiencing barriers that are not present for non-disabled women and Disabled men. At the other-undergraduate level there appears to be an effect of disability such that Disabled women are more likely to continue at their institution (suggesting that they are not completing their studies within the expected timeframe), less likely to gain their intended award, and increasingly likely to leave with an other than intended award. At postgraduate-taught level the differences in continuation category become more pronounced, with Disabled women increasingly either leaving with an other than intended award, being dormant, or leaving without an award. The data also show that the attainment gap identified by Hector et al. (2020) is affected by gender, such that Disabled women out-perform Disabled men, but are still gaining “Good Honours” at a lower rate than non-disabled women.

While using national data allowed analysis of the whole sample of students at UK HEIs, it is nevertheless limited in that it cannot provide understanding of the reasons for any of the findings presented here. Additional research is needed to unpick the trends identified here. The research also only examined the intersection of gender and disability. There is also an urgent need for research which examines the intersections of disability, race, gender identity, and sexuality.