Introduction

Cuban Residents Abroad (hereafter CRA) form part of the Great Cuban Nation, contribute significantly to the wellbeing of their families on the Island, and potentially can participate in its economic transformation and development. They can be particularly valuable to the local development of their communities of origin and others to which they are linked by personal, family, and social links, be they cultural, professional, or other, ties as diverse as their own characteristics and migratory experiences.

Ten percent of the Cuban population has emigrated and, if we include their descendants, around 2.4 million, or 21.6% of the 11.1 million Cubans (2021), live permanently outside their country of origin (GEMI 2023b).

According to a Pew Research Center analysis of the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, an estimated 2.3 million Hispanics of Cuban origin lived in the United States in 2017. Cubans in this statistical profile are people who self-identified as Hispanics of Cuban origin, which includes immigrants from Cuba and those who trace their family ancestry to Cuba. In 2004, 56% were foreign born, 43% of foreign-born Cubans had been in the US for over 20 years, 58% of foreign-born Cubans were US citizens: 5.8% of the Cuban population lived in Florida and 0.9% lived in New Jersey (Noe-Bustamante et al. 2017).

Another 800,000 maintain their residency in Cuba but have been abroad for more than 24 months. We can assume that many of them have in fact fixed their principal residence abroad and come to Cuba for brief or more prolonged visits to maintain their residence status. All of them are actual or potential contributors to the country’s economy, through their travel for family visits, tourism, work, business, sending money remittances, importing and exporting goods – supposedly for personal use only – or by informal investments in private enterprises of self-employed workers (called TCP in Cuba, “trabajadores por cuenta propia”) and micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (called MIPYMES in Cuba, “micro, pequeñas y medianas empresas” ).

This study looks at the current and potential contribution of the CRA to the Cuban economy, with emphasis on local development, through the activities of tourism and remittances. Given the limited information available for these topics, the methodology employed is the analysis-synthesis of primary and secondary sources. Whenever possible, statistical data and their corresponding sources are presented as part of the results.

Following this Introduction, we next characterise the population of CRA and their relation to the Cuban nation. Then we explore the current participation of CRA in the activities mentioned above, and the internal and external obstacles that the country faces to maximise their contribution in each area. Finally in the concluding section we present a series of proposals on how to increase this support and to channel it in such a way as to achieve the maximum impact for the Cuban economy and society.

Cuban Residents Abroad

At the close of 2022, the Cuban government registered some 2.4 million Cubans residing abroad, of which 600,000 are foreign-born descendants. The United States is the leading destination of Cuban migrants, although the last few decades have witnessed a diversification of destinations of Cuban emigration. The other principal countries where Cubans have settled, according to estimates of the General Directorate of Consular Affairs and Attention to Cuban Residents Abroad (Cuban acronym, DACCRE) of the Ministry of Foreign Relations (MINREX), are:

Approximately 1.1 million Cubans have entered the United States since 1959. Including descendants, an estimated 2 million – 85% of the total number of CRA – live in the United States, while 5.3% live in Spain and 1.5% in Venezuela (GEMI 2023b).

Since 2021, some 400,000 Cubans have entered the US. In Fiscal Year 2022 alone, more than 313,000 irregular Cuban immigrants arrived, with 42,640 just in the month of December (GEMI 2023a). This led the US Government to announce in January 2023 the Humanitarian Parole Program for Cubans, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Haitians wanting to emigrate to the US. Through the end of September 2023, 50,185 Cubans arrived and were granted parole (US Customs and Border Protection 2023), 18% of whom were professionals or technicians (GEMI 2023a).

On 14 January 2013, Decree-Law No. 302/2012 came into effect in Cuba. This modified the 1976 Migratory Law, and extended the time of stay of Cubans travelling abroad to 24 months while still conserving their permanent residency. They had to return to the country within that time and renew their passports, which lasted for six years but required renewal every two years.

The number of Cubans who travelled and lived temporarily abroad increased to 84% of the total number of trips between 2013 and 2016, compared to 16% between 2008 and 2012. This led to an increase in the number of Cubans with family abroad to 3,547,523, which represented 32.1% of the resident population (Rodríguez 2019).

In July 2023, the duration of the Cuban passport was extended from six to ten years, and the requirement that it be renewed every two years was removed. The condition that Cuban citizens return to Cuba in the span of 24 months in order to maintain their condition of permanent residents or request an extension (MINREX 2018) was waived in 2020 when many of the flights to Cuba were suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing Cubans to enter the country with an expired passport and renew it before leaving again. MINREX has continued to waive this requirement, which means that in practice all Cubans with a valid passport can either maintain their permanent residency if they left after 2012, or are eligible to recover it if they desire and can demonstrate that they have a valid housing arrangement in Cuba (own a home or live with a relative).

Over 914,000 additional Cuban residents in the country were travelling abroad at the close of 2022 according to official sources, the majority without losing their residence status (CEDEM 2023). They constitute the so-called temporary or circular migration.

The figures presented above suggest a wide range of possibilities for establishing greater relations of mutual benefit between the Nation and the Cuban émigré community.

How does the Cuban State Relate to This Migration?

DACCRE is the government office that deals with CRA. Cuba has 140 Consulates throughout the world – 39 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 40 in Africa, 36 in Europe, 3 in Canada, and 21 in Asia – that interact with this population. There is only one in the United States, at the Cuban Embassy in Washington DC, due to US government restrictions resulting from the bilateral conflict. It has the impossible task of servicing over a million of its nationals in that country.

With the exception of the United States, many CRA maintain links with the embassy and consulates in their country of residence. These bonds should be made stronger. In the words of Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez to Cuban émigrés in New York in September 2023, “we aspire to stimulate relations with the new generations of Cubans living abroad, by strengthening the cultural and historical bonds with their or their parents’ country” (Robbio 2023).

In truth, these links can be strengthened much more and contribute to the development of the country, if they promote visits, investment, and cooperation. Ana Teresita González Fraga, Vice-Minister of Foreign Investment and Trade, declared at the “IV Conferencia La Nación y la Emigración” held in Havana in November 2023, a meeting with Cuban nationals living abroad:

In the strategy for economic and social investment to achieve greater prosperity for our people, Cuba counts on the participation of Cuban citizens living abroad, through businesses supported by the foreign investment law, foreign trade operations, and actions of international cooperation. (González Fraga 2023)

Yet, as we shall see, many obstacles remain, whether due to outdated regulations, inconsistent sectoral policies, resistance and fear at the local level of the consequences of mingling with CRA, or general “negative subjectivity” by part of the population resulting from rejection and condemnation of those who left the country in previous decades.

Contributions to Cuba’s Economy from CRA Tourism and Remittances

Tourism potential of Cuban residents abroad

The popular image of tourism in Cuba is that of foreigners arriving by air or sea to stay in hotels and private homes, or as cruise ship passengers. Travel by CRA is not viewed as tourism even though in many cases it is, at least in part.

The motivations to travel to Cuba by those nationals, particularly immigrants, are varied and often diverse. Primarily they come to visit family and friends, but also for pleasure, sun and beach, nostalgia, or to discover their roots, all of which they often do in the company of their local family. In other cases, the visits are associated with a process of re-establishing their residence in Cuba, purchasing properties, investing in private businesses, or importing goods purchased in their country of residence to sell in Cuba. In all of these cases, they have an impact on the local economy equal to or greater than foreign tourists.

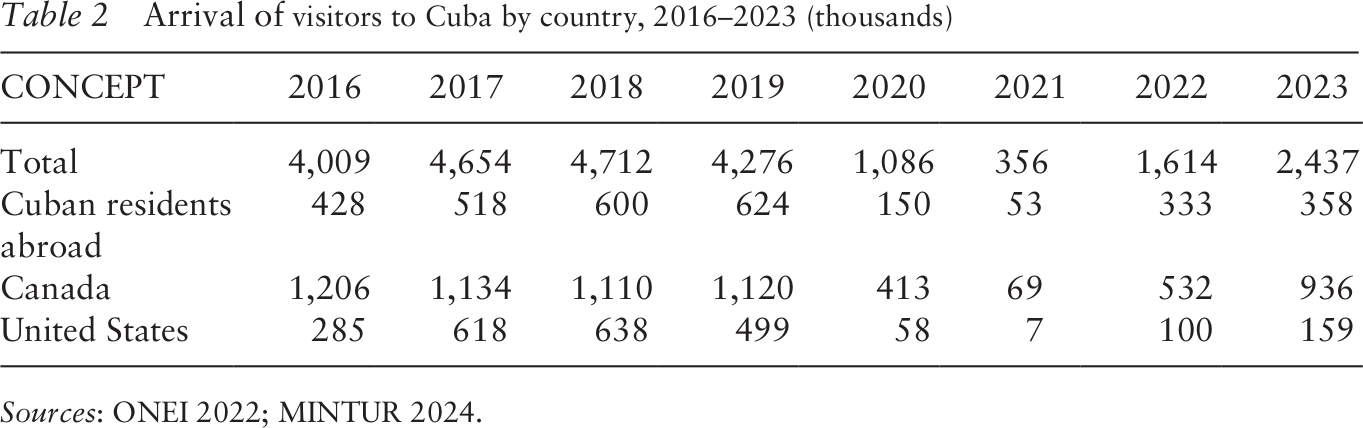

Since 2016 the Cuban community abroad has been the second largest source of visitors to Cuba after Canada, with the exception of the United States in 2017 and 2018 during the “Obama Spring”. Some 624,000 persons bearing Cuban passports arrived in 2019, the highest figure to date. In 2023, Cubans made up 14.6% of arrivals, some 358,000, with 85% of these from the United States. In the same period, 159,000 arrived with US passports, an undetermined number of whom were descendants of Cubans.

Arrival of visitors to Cuba by country, 2016–2023 (thousands)

Sources: ONEI 2022; MINTUR 2024.

With the drastic decline in tourism beginning in 2020, the number of arrivals of CRA also fell, but their proportion of the total arrivals rose from 11% in previous years to 14–15%, a sign of the resilience of travel by CRA. 2

The government of Donald Trump (2017–2020) reversed many of the measures of rapprochement to Cuba taken by the Obama administration, culminating in 243 new sanctions and coercive measures toward the island. Among them were a series of measures that limited individual and “people-to-people” travel of US nationals, prohibited lodging in most hotels that are property of the State, restricted commercial flights to only the Havana International Airport, and, by including Cuba in the State Sponsors of Terrorism (SSOT) list, required foreigners of many European and other countries who can visit the US with a visa waiver (ESTA) to obtain a visa at a US Consulate if they have previously travelled to Cuba. This has had a dampening effect on foreign tourism in general.

In May 2022 the Biden Department of State announced it would repeal some of these sanctions, which included allowing commercial airlines to land at airports in all of the provinces (Kornbluh 2022). This was certainly a factor in the six-fold increase in arrivals of CRA to Cuba compared to the previous year.

An even more important index to measure the impact of tourism than the number of arrivals is tourist-days – the number of tourists times the number of days of their stay. In 2018, CRA averaged 11.2 days of stay for a total of 6,723,460 tourist days. The average for all international visitors was nine days (Perelló 2019).

Tourists staying in private homes average two to three times the number of days of stay compared to those lodged in hotels, and thus their impact on the local economy is much greater. Although many assume that CRA stay with their family and do not pay rent, we do not know how many rent private lodging or stay at state-owned hotels. Insofar as CRA stay more days than the average foreign tourist and tend to lodge in private accommodations, whether paying rent or not their contribution in cash and in-kind to their family in Cuba, plus their own expenses, constitute an important contribution to local economies, both to the private and the state sectors.

Émigré visits also contribute to the statistics of stays of domestic tourists (8.1 million in 2019). This is because it is often the case that when CRA invite their families to stay together at a tourist hotel, it is a local family member that makes the reservation, and thus statistically it is registered as domestic tourism.

In summary, although it is difficult to quantify due to a lack of data, the economic impact of travel by CRA in Cuba is significant, particularly for private and local economies. Their resilience in the face of the restrictive measures of the Trump–Biden Administrations with a sustained increase in their arrivals, even in 2019 when the general tendency was to decline, and a relatively smaller reduction in subsequent years, speaks to the strength of family and cultural ties between the Nation and its immigration (Betancourt 2020).

The potential contribution of tourism by CRA is not limited to the economy. They can contribute to improving the welfare of people, conserve natural resources, and preserve national culture. Well-managed tourism is a powerful tool for promoting prosperity, quality of life, and community development.

The contribution of remittances

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines remittances as broadly understood as personal money transfers and goods that a migrant worker makes to his/her relatives and friends in the country of origin 3 (IOM n.d.).

According to the Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), “Migrant remittances grew almost 30% in 2021 and continue to be a very important source of foreign resources for the countries of the region, particularly for Central America, Mexico and some Caribbean countries” (CEPAL 2022). For Cuba it was different. Beginning in 2017, the Trump administration restricted the flow of remittances sent by Cuban-Americans to Cuba to 1,000 dollars per quarter and only to family members.

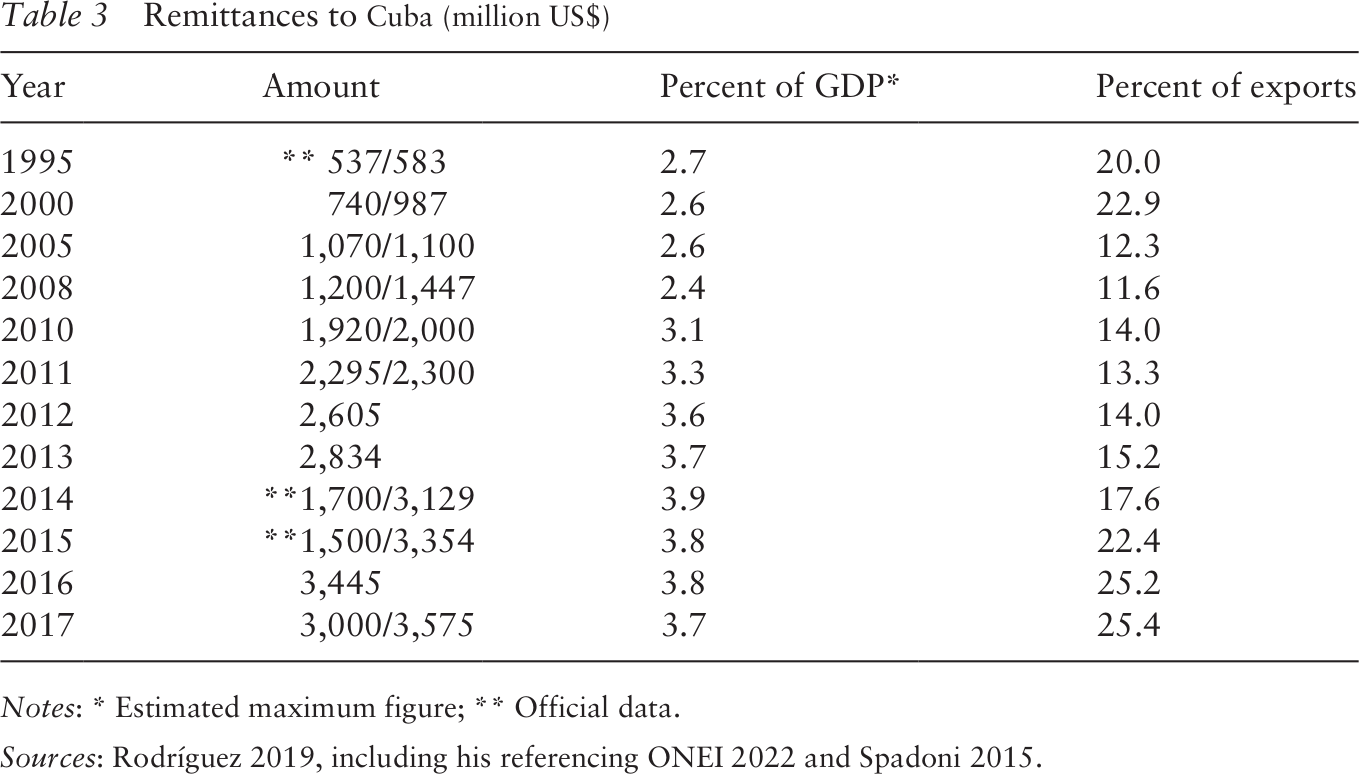

While Cuba seldom publishes official figures on the remittances it receives, there exist estimates made by foreign entities, albeit they vary significantly (Runde 2021). The following data show the maximum and minimum figures of the different estimates of remittances received between 1995 and 2017, corresponding primarily to those sent from the United States:

Remittances to Cuba (million US$)

Notes: * Estimated maximum figure; ** Official data.

Sources: Rodríguez 2019, including his referencing ONEI 2022 and Spadoni 2015.

The Havana Consulting Group (THCG), headquartered in Miami, Florida, combined its estimates of money remittances and the value of goods imported by visitors, or remittances in kind, with the goal of portraying total remittances to Cuba as high as possible. THCG does not reveal either its methodology or the sources of their estimates which makes it impossible to validate them, and the clearly anti-Cuba political objectives of their publications make their estimates questionable (Morales 2023a). But they are one of the few entities that ventures to publish these, and are thus cited by many scholars.

According to THCG, total remittances peaked at US$3,717 million in 2019, “which fuelled the significant growth of Cuba’s emerging private sector” (Havana Consulting Group 2019). After the COVID-19 pandemic, the flow fell 63% in 2020 and another 46% in 2021, followed by a recovery in 2022 to US$2,040 million. This represents an 88.2% increase with respect to 2021, but is still 41.5% below the average annual figure for the period 2014–2019 which was US$3,485 million (Morales 2023b).

Morales’s estimate for 2023 is US$1,973 million, a 3.1% decrease with respect to 2022, “the only country to experience a decrease in remittances received in the Latin America region”. One reason for this decline, Morales speculates, is the significant migration of Cubans to the US in 2023 under the aegis of the US Humanitarian Parole Program; that has become a priority for their sponsors in the US and thus reduced the remittances that they would have sent to their families on the island (Morales 2024).

Runde considers that, despite the differences in estimates, remittances constitute the third source of foreign earnings for Cuba, after the export of services and tourism.

To put it in perspective, Cuba’s GDP was US$103 billion in 2019, with a net contribution of official development aid of US$499 million and remittances of US$2–US$3 billion. In comparison, in 2019 Haiti received US$3.3 billion in remittances, Honduras US$5.4 billion, El Salvador US$5.6 billion, Guatemala US$10.6 billion, and Mexico US$39 billion. (Runde 2021)

Jose Luis Rodríguez opines that approximately 50% of remittances received are destined for investments or working capital for private enterprises on the Island (Rodríguez 2019). This would represent in 2017 approximately US$1,750 million in remittances invested in the private sector, versus an estimated US$875 million in foreign direct investment (FDI) in the State sector in that year.

Measures and countermeasures

In 2020 the Trump administration imposed US dollar limits on cash remittances and aid packages sent from the US to Cuba, restricted those sent by non-family members, and prohibited US providers like Western Union from operating with the Cuban remittance processors, FINCIMEX and American International Services, because they allegedly belonged to the GAESA conglomerate of military enterprises. Havana blamed Washington for having to close down over 400 Western Union bureaus in Cuba and for the drastic fall in the volume of remittances (Cubadebate 2023).

In May 2022 the government of Joseph Biden reversed some of the measures imposed by his predecessor, among them cancelling the US$1,000 per quarter limit for family remittances and authorising “donor remittances” (non-family) “to support independent businesses” (Kornbluh 2022).

Previously that year, the Cuban State enterprise, Orbit SA, a subsidiary of the Central Bank of Cuba, received authorisation from the Cuban government to operate and provide similar services to those previously offered by FINCIMEX (Cubadebate 2023). In January 2023, the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) approved the renewal of remittance services between the US and Cuba through Western Union and other providers with Cuba’s Orbit as receptor. Western Union announced a trial period where they would process remittances from 24 locations in the Miami area, to be deposited in MLC (convertible currency) accounts of the beneficiaries at the Banco Popular de Ahorro (BPA), Banco Metropolitano (BM), and Banco de Crédito and Comercio (BANDEC). OFAC also authorised the Miami agencies, Cubamax and VaCuba, to operate with Orbit SA, to send remittances from the US to Cuba (AFP and Reuters 2023). In March 2023, Western Union announced that it would expand its services of remittances to Cuba to its more than 4,400 establishments in the US and Puerto Rico, and through its digital platform, WesternUnion.com, and its mobile application. Clients can send up to US$2,000 per transaction to Cubans with accounts or debit cards in the aforementioned banks. The money is deposited in US dollars, although the accounts operate in MLC. For its part, Orbit S.A. announced that it planned to expand its operations in the US and continue processing remittances from Canada and Europe (Gámez Torres 2023).

Remittances in kind

The import of merchandise as accompanied baggage and cargo shipments sent separately by passengers, whether by Cuban residents abroad or residents in the country that travel abroad, represents an important form of remittances in kind. It should be noted that remittances of goods or services are not included in the international statistics on the volume of remittances, which makes any international comparison impossible. But despite the difficulties involved in their quantification, these imports increase the resources available to the beneficiaries, be they for consumption or for investment.

Since 2019, the Cuban government stopped collecting customs duty on the non-commercial import of foodstuffs and medicines by individual travellers, and reduced duties on other imported products by individuals for personal consumption. It is commonly known that many of these products end up being sold, whether directly to consumers or indirectly by small private shops, but the authorities have chosen to look the other way. At the same time, private businesses are importing foodstuffs for sale in a multitude of stores and paying the corresponding duties.

Recently a number of e-commerce platforms have appeared in Cuba, such as Katupulk, Supermarket 23, Mall Habana, and Tuambia, with payment abroad. Most are owned by Cuban residents abroad, based in Spain, Canada, and other countries. They have developed their own logistics centres with transportation, warehousing, and cold storage in Cuba, independent of the State but often renting their facilities. They offer imported as well as domestically produced goods, purchased from both the State and private sectors.

Like the private food stores and “delicatessens”, these platforms are also providing inputs for food production and packaging to private and state meat, poultry, dairy, bakery, and other food processors, with whom they barter in exchange for finished products that are then sold by their businesses. These “production chains” contribute to development and to import substitution of finished products. E-commerce is allowing Cuban families with relatives and friends abroad to increase their consumption of food and other consumer items, and is invigorating domestic production in the process.

Nevertheless, the earnings from these transactions seldom enter the domestic banking system. Since Cuban banks cannot receive US dollar deposits because of the blockade, e-commerce platforms use payment gateways that work with Spanish or other banks, where the smartphone works like an electronic wallet. Therefore, these remittances, like the cash that is hand-carried by travellers, the so-called “mules”, are not deposited in banks and are thus independent of the State sector. In effect, for CRA, e-commerce platforms constitute a new way of sending remittances in kind – fundamentally food – to families and friends in Cuba.

Obstacles to Taking Full Advantage of the Potential Contribution of CRA

We have characterised the potential for contribution of CRA to the Cuban economy through tourism and remittances. But what are the obstacles that exist which limit this potential from being fully realised?

Tourism

In July 2020, the Tourism Minister reaffirmed the willingness of the country to receive international tourism in Cuban hotels, the interest in promoting events tourism, and specialised tourism in diving, nature, and culture (Cubadebate 2020). However, he did not mention anything about family visits or the need to consider the demands and needs of CRA travellers, the second largest group of visitors to the country.

The reason may be in part because the image of tourism to Cuba is one of foreign visitors arriving in groups, lodged in state-owned hotels, and transported by tourist buses to State-owned restaurants and shops. Their expenditures, even though they may be modest, are collected by the State sector and reported as tourism income. CRA travellers, on the other hand, function typically outside this “tourism circuit” and spend mostly in the private economy, contributing to the local economy, which is not quantified and is undervalued.

But there is also what the scholar Jesús Arboleya calls “negative political subjectivity which exists in certain strata of the government and some sectors of Cuban society with respect to the question of migration and relations with emigrants”. This hinders “the promotion of attractive offers for their travel to the country”, and “also limits the objective and balanced treatment of the issue on the part of the official Cuban media” (Arboleya 2022).

A person born in Cuba requires a valid Cuban passport in order to enter the country, even if she/he holds another citizenship. The costs of obtaining or renewing a passport and other consular services were also lowered for CRA in July 2023, in line with fees paid by Cubans residing in Cuba and with international standards. This resolved a long-standing complaint of CRA who had to pay extra high fees for obtaining or renewing their Cuban documents in order to travel to the Island and maintain contact with their country of origin. It had become a particular disincentive for Cubans living in the US where the only Consulate is in Washington DC, which meant that most had to go through an agency to obtain their documents, adding an extra cost to the process. By the time the IV Conference “La Nación y la Emigración” (The Nation and the Emigration) was convened by the Cuban government in November 2023, attended by 371 Cubans living abroad (and some already with dual residence on the Island), this long-standing demand had been met, and relations between the Nation and its diaspora advanced to encompass other issues such as furthering the integration of the latter in the life of their country of origin.

Remittances

The measures taken by the Biden Administration after the announcements of May 2022 and the renewal by Western Union and other US agencies of remittance service to Cuba in 2023 suggests a gradual recovery of formal monetary remittances in the years to come. To date, neither Orbit SA nor Western Union and the other US agencies, nor the government of Cuba, have reported the value of remittances sent to Cuba in 2023.

According to a report by the Center for Democracy in the Americas (CDA) and The Washington Office on Latin América (WOLA), what the Biden Administration needs to do is revert the statutes set by the Cuban Assets Control Regulations (CACR) and the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) with regard to Cuba to their status on 20 January 2017 when Trump assumed the presidency. “No other international economic flow except remittances has such a direct, immediate benefit for the standard of living of Cuban families. A vibrant civil society relationship will empower the Cuban people and lay the foundation for enduring reconciliation”, concludes the report (WOLA and CDA 2020: 4).

Conclusions: Recommendations for Increasing the Contribution of CRA to the Cuban Economy

Travel to the Island and remittances sent to family and friends will continue to be two of the principal sources of foreign revenue for Cuba in the future, and CRA are an important source of both. Based on the analysis contained in this study, we propose the following actions that Cuba can take to increase the contributions of travel and remittances sent by CRA.

Tourism

Having reduced the cost of obtaining passports and other consular services and maintaining the moratorium on the requirement that residency be renewed after 24 months abroad, the Cuban government has benefitted all Cubans who live or travel abroad, which paves the way for an increased number of visitors and longer stays. This translates into higher tourism income. However, some obstacles remain which should be reviewed, such as special requirements for obtaining passports for those who emigrated before 1970, and conditions placed on those long-time emigrants who want to return to Cuba to live.

Reduce further or waive altogether the payment for passports of Cuban minors. Establish a differentiated tariff for visas of descendants of Cubans born abroad. Besides encouraging the visits of Cuban descendants, this would provide information about their number and country of residence or origin, by differentiating them from others who enter with foreign passports.

Decentralise decision-making capacities in issues concerning tourism in favour of the territories. By recognising the importance of localities as the fundamental scenario of family tourism, local institutions can gather information about Cuban immigrant visitors and their local families, and design specific tourist attractions and programs for their consumption. Given the importance of the local hosts for this modality of tourism, it is important to include the input of local families and friends, who decide in great measure the activities and expenditures that the visitors undertake. Municipal governments could commission studies on these immigrant visits to their place of origin and listen to the opinions of family members as to what services they may demand. These local initiatives contribute to inserting CRA into their country and territory of origin, founded on the local identities and traditions of each territory.

Offer products and services adjusted to the CRA market. One of the immediate actions could be systematising the offers of medical and dental services available to Cubans living abroad who visit the country, at competitive rates, and whenever possible, covered by the patient’s foreign insurance policy. This would legalise and institutionalise the medical services that some emigrants already receive illicitly, using the identity documents of their resident relatives. The prestige earned by Cuban medicine is credible and impelling to Cuban immigrants, and many of these lack adequate medical or dental care in their country of residence. By making these differentiated services available at the local level, Cuban families can inform their relatives abroad of the benefits of organised and legal medical services that are available to them on the Island.

Support the local tourism industry, which is more agile in responding to the demands of the CRA and their local hosts than country-level tourist institutions, with offers of lodging in hotels and villas, transportation, food, and tailor-made excursions. Currently, most activities related to tourism except lodging and food services are prohibited to private providers by Decree 49/2021 (Consejo de Ministros 2021). These services already exist in the informal economy, which operates outside the legal system and does not pay taxes. Allowing private entities to also provide them would benefit all parties.

Remittances

Facilitate the transmission of remittances and create incentives to promote them. For example, the government could allow for the creation of other transmitting and receiving agencies, offshore agencies, use of bank cards, APKs, etc. Prime Minister Manuel Marrero announced before the National Assembly in December 2023 that one of the measures that will be taken to increase the country’s hard-currency revenue is to “recover the flow of remittances”, though he provided no details (Díaz Ballaga et al. 2023).

Promote “productive remittances”. Create mechanisms for CRA to provide investment capital and ensure an adequate return to investors and/or family members. The volume of resources that enters the country associated with remittances deserves an adequate treatment, resulting in benefits for all parties, including the Cuban State which today barely benefits at all from this important source of revenue. There exists a concrete project of productive remittances with the initial aim of housing construction that was presented to the Central Bank and approved, but has not been implemented. It will be necessary to organise a business venture, preferably a joint venture with foreign direct investment, to manage this business, with the necessary guarantees and efficiency (Rodríguez 2021).

Facilitate remittances in kind and imports for the retail sector. Review the current norms that enable or inhibit remittances in kind. Currently, imports by travellers of food and medicines in their luggage and cargo shipped separately destined for personal consumption are permitted without payment of customs duty, but it is widely known that much of this ends up being sold in the informal market. Imports of processed foods by private MIPYMES have soared to more than US$1 million in 2023, which has helped compensate for the shortage of imported products in state-owned stores that sell in MLC. In December 2023, Prime Minister Marrero announced a “50% reduction in customs duties for imports of raw materials and intermediary goods, especially for agricultural production”, but increases in “customs duties on finished products for retail” in 2024 (Díaz Ballaga et al. 2023).

Similarly, the e-commerce platforms constitute a new way to send remittances, in this case in specie, to family and friends in Cuba. They are increasing the consumption of one sector of Cuban families – those with relatives and friends abroad – and stimulating national production. To continue facilitating them contributes to the supply of consumer goods and to the domestic economy.

The downside of remittances is the increase in inequality that they aggravate. With the downturn of the Cuban economy and particularly the inflation that has driven down the value of the Cuban peso relative to foreign currencies, those on fixed peso incomes, including State-sector salaried workers and retired persons on pensions, have seen a drastic fall in their purchasing power. Their capacity to consume basic goods and services, such as food, medicines, fuel, transportation, and housing, has plunged. This has driven many to look to the State for relief through subsidies available for the more vulnerable sectors of the population, or to emigrate in search of a better quality of life. Those who enjoy higher incomes – farmers, self-employed workers, artists, business owners, earners of US dollar incomes in the foreign sector, persons who travel abroad for work or to bring back merchandise for sale – and particularly those who receive remittances from families abroad – are able to escape the shortages to a greater or lesser degree, by accessing the parallel market where prices are set by supply and demand.

In summary, there are clearly many obstacles to the full and wide-ranging insertion of Cuban residents abroad into the Cuban economy through travel to the Island and contributing monetary and in-kind remittances. In order to overcome these, firstly, the government should establish a policy that facilitates and encourages travel by CRA and their families to Cuba, and their contribution to local economies. Second, policies are needed to hasten and maximise the impact of remittances as a source of foreign revenue and to increase the value of imports by the private sector, without compromising the State’s resources.

What is desired is not to open the gates without order or organisation. On the contrary, what is needed is to define what to do to regulate their incidence and contribution via national policies, avoiding administrative decisions taken by individual ministries or territories. It is clear that the opportunity exists to guide this process in a coordinated way for the benefit of both the 2 million Cubans residing abroad and the nearly 11 million who continue to live and struggle to prosper on the Island.

The above-mentioned “negative political subjectivity” that endures in certain strata of government, the public mass media, and some sectors of Cuban society with respect to emigration and maintaining relations with immigrants, dampens the economic contribution of CRA and their insertion in the country and society of origin, and frustrates the political influence favourable to Cuba that they could exert in their countries of residence.

If the aim is to boost the visits and remittances of CRA, it is essential to reconcile and amend the regulations and practices of all agencies and institutions that intervene in the process, including the academic and professional sectors that can contribute with information, research, and training. It is also imperative to engage Cuba’s emerging private sector to provide more and better goods and services for both residents and visitors. Promoting the participation of CRA, and in particular their contribution to local development, should become a national policy that embraces all sectors, public and private.