Introduction to the october crisis

The October Crisis was one of the most dangerous moments of the twentieth century and the Cold War, and perhaps even in the whole history of humanity. Suddenly, the unthinkable – a total war between US and the USSR, and the nuclear holocaust that probably would have been the consequence – was a real possibility. The prelude to the crisis can be found in US acts of aggression against the Cuban Revolution following the removal of the US puppet government headed by Fulgencio Batista at the start of January 1959. The US launched a number of activities which were more or less of a state-organised terrorist character to overthrow the new revolutionary government led by Fidel Castro; these activities escalated during 1960-1961 within the framework of a trade embargo, terrorist attacks and the destruction of parts of the Cuban sugar harvest, and were then crowned by the landing of c. 1800 US-trained exile Cubans at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961 with orders to start a military counterrevolution. This operation was a total failure, both militarily and politically, being swiftly defeated by the Cuban forces (Diez Acosta 2014; Jiménez Gómez 2015; Karlsson and Diez Acosta in press, ms).

This last act of aggression, along with the knowledge that a new invasion plan would be launched in 1962, led the revolutionary Cuban government to accept the military assistance that was willingly offered by the Soviet Union. A military accord between Cuba and the Soviet Union was signed in May 1962 and it also included, beside a huge number of troops from all military branches, the installation of medium- and long-distance strategic nuclear missiles in Cuba. The transfer of the missiles as well as other military equipment and staff began in secret from July 1962 onwards, under the name Operation Anadyr (Diez Acosta 1992, 1997, 2002a 19–c; Jiménez Gómez 2015; Karlsson 2017; Karlsson and Diez Acosta 2019). On 14 October, the illegal US reconnaissance flights over Cuba that had been taking place since 1960 revealed that nuclear-capable missiles had been installed at a number of sites, and this was the spark that ignited the October Crisis.

The missiles were medium-range missiles named R-12 by the Soviets and SS-4 by NATO. Thirty-six were deployed at seven different sites, and each missile contained a nuclear warhead 75 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. They had a range of 1,400 miles (approx. 2,250 km), which meant that they could reach Washington, DC, and central parts of the US. Two installations were also built for long-distance missiles (R-14/SS-5), but they were never operational, as the US naval blockade/quarantine that began on 24 October prevented the warheads from reaching Cuba (Diez Acosta 2002a, 2002c: 118–19; Karlsson 2017). In parallel to the blockade, intensive negotiations were taking place between Washington and Moscow. In this extremely tense situation, an accident or ill-considered action on either side could have started a nuclear war (Kennedy 1969: 127; Blight et al. 1991; Blight et al. 1993). During the 13 days that followed 14 October, the world stood on the brink of a thermonuclear holocaust.

Despite the US plans for a direct military attack on Cuba with the aim of removing both the missiles and the Cuban revolutionary government, the crisis was solved through diplomatic negotiations both in the UN and directly between the two superpowers. At the end of October, the US and the Soviet Union reached an agreement without the participation of the Cuban government, in accordance with which the Soviet missiles and all offensive weapons installed on Cuba were dismantled and shipped back to the Soviet Union during November. The agreement also had a secret part, in which the US promised to withdraw nuclear Jupiter missiles in Turkey and not to intervene militarily in Cuba in the future (Diez Acosta 1992, 1997, 2002a, 2002c; Jiménez Gómez 2015; Karlsson and Diez Acosta 2019).

The highest levels of the October Crisis have been extensively documented and investigated by historians, with a focus on its significance for world politics during the Cold War and encompassing the military-strategic dimensions, top-level diplomacy and the leadership of the two superpowers etc. (cf. Garthoff 1987; Allyn et al. 1992; Blight et al. 1993; Gribkov and Smith 1993; Fursenko and Naftali 1997; May and Zelikow 1997). However, most of these investigations adopt a narrow perspective that is aligned with the standpoint of the US and its allies, and there are only a few investigations that present the crisis from a Cuban perspective (cf. Diez Acosta 1992, 1997, 2002a, 2002c; Jiménez Gómez 2015; Karlsson and Diez Acosta 2019).

However, in general, this continuous presentation of the narrative of the crisis in the form of its development and internal dynamics has meant that other aspects of the crisis have been neglected and suppressed. This applies not least to the material remains found at a number of the nine former missile sites, and to the memories and stories of the people from the nearby villages and surrounding communities – memories and stories that constitute unique testimonies of how this world-crisis was perceived by people who suddenly and unexpectedly found themselves situated in the political epicenter of the crisis. During the decades that followed the crisis, it was also under-communicated in Cuba, despite the fact that nuclear missiles had been deployed on Cuban soil and Cuba’s central significance to the event (cf. Diez Acosta, 1997, 2002a, 2002c; Burström and Karlsson 2008; Burström et al. 2009; Burström et al. 2011; Karlsson 2017).

Points of departure

Since 2005, a contemporary archaeology project has been exploring the material and immaterial remains of the October Crisis in Cuba, at six out of a total of nine sites where Russian nuclear missiles were located in October 1962, using the neglected dimensions identified above in order to gain new insights about the October Crisis and its human dimensions, and to complement the dominant narration of the crisis (see Figure 1) (Burström and Karlsson 2008; Burström et al. 2009, 2013; González Hernández et al. 2014; Iglesias Camargo et al. 2016; Gustafsson et al. 2017; Karlsson 2017, 2020; Karlsson and Diez Acosta 2019).

Map showing the six sites where the project has worked. From west to east: El Cacho, El Pitirre, Santa Cruz de los Pinos, La Rosa, El Purio and Sitiecito. Illustration: Håkan Karlsson.

At an overall theoretical and methodological levels, the project and its investigations, as well as this text, are anchored in a contemporary archaeological approach, and in a critical interest in the material remains of our times and what they can tell us about our world. This means that it gathers its inspiration from a number of perspectives, authors and sources, such as, for instance, the archaeology of conflicts and battlefields and the material and immaterial remains from the Cold War (cf. Schofield 2005, 2009; Schofield and Cocroft 2007; Saunders 2012; Carman 2013; Hanson 2016; Landa and Hernández de Lara 2014, 2020), critical heritage approaches and the use and role of archaeology, history and cultural heritage in the contemporary and future society (cf. Smith 2004, 2006; Harrison 2010, 2013; Harrison and Schofield 2010; Biehl et al. 2014; Olsen and Pétursrdóttir 2014; Holtorf and Högberg 2015; González-Ruibal 2016, 2019; Harrison and Breithoff 2017). Such an archaeological approach, is naturally multidisciplinary to its nature, since it combines information from material, written and oral sources, and since it strives to let this information interact in a way which means that new forms of knowledge and narrations can be produced (cf. Buchli and Lucas 2001; Holtorf and Piccini 2009; Burström 2010; Graves-Brown et al. 2013).

Towards this background the project has produced (and continues to produce) new knowledge concerning the exact location of different material structures on a number of the former missile sites, the reuse of material remains and objects from these bases on the surrounding countryside and in nearby villages, and the memories and narrations held by peoples living at these places. Thus, it has been possible to contribute with many-sided material and immaterial voices “from below”, which add human dimensions that can complement, enrich and question the dominant narrative of the October Crisis (Burström et al. 2009, 2013; González Hernández et al. 2014; Gustafsson et al. 2017; Karlsson 2017, 2020; Karlsson et al. 2017; Karlsson and Diez Acosta 2019). This is important since the material remains at the former missile sites do not have any antiquarian protection within the framework of the Cuban laws, and since the persons that have direct and personal memories from the crisis are aging rapidly, and disappearing.

The current text focuses on material remains in the form of the US Marston mats that can be found at a number of locations in farmsteads and villages surrounding the former missile sites in the Los Palacios and San Cristóbal areas, as well as on a photo of a Russian girl that was a gift from a Soviet soldier to a Cuban peasant. It seeks to answer:

The US marston mats

When the project carried out its first field activities in 2005 at the former Soviet nuclear missile site at Santa Cruz de los Pinos, in the province of Artemisa, western Cuba, we already found perforated metal mats that were being reused in a number of ways in the local community of San Cristóbal and in the countryside surrounding the site (Burström et al. 2009; Burström et al. 2013; Gustafsson et al. 2017; Karlsson 2017, 2020). At that time, we understood that this equipment had been used for reinforcing the ground for heavy vehicles, but we did not know that they were Marston mats, and we did not know anything about their history.

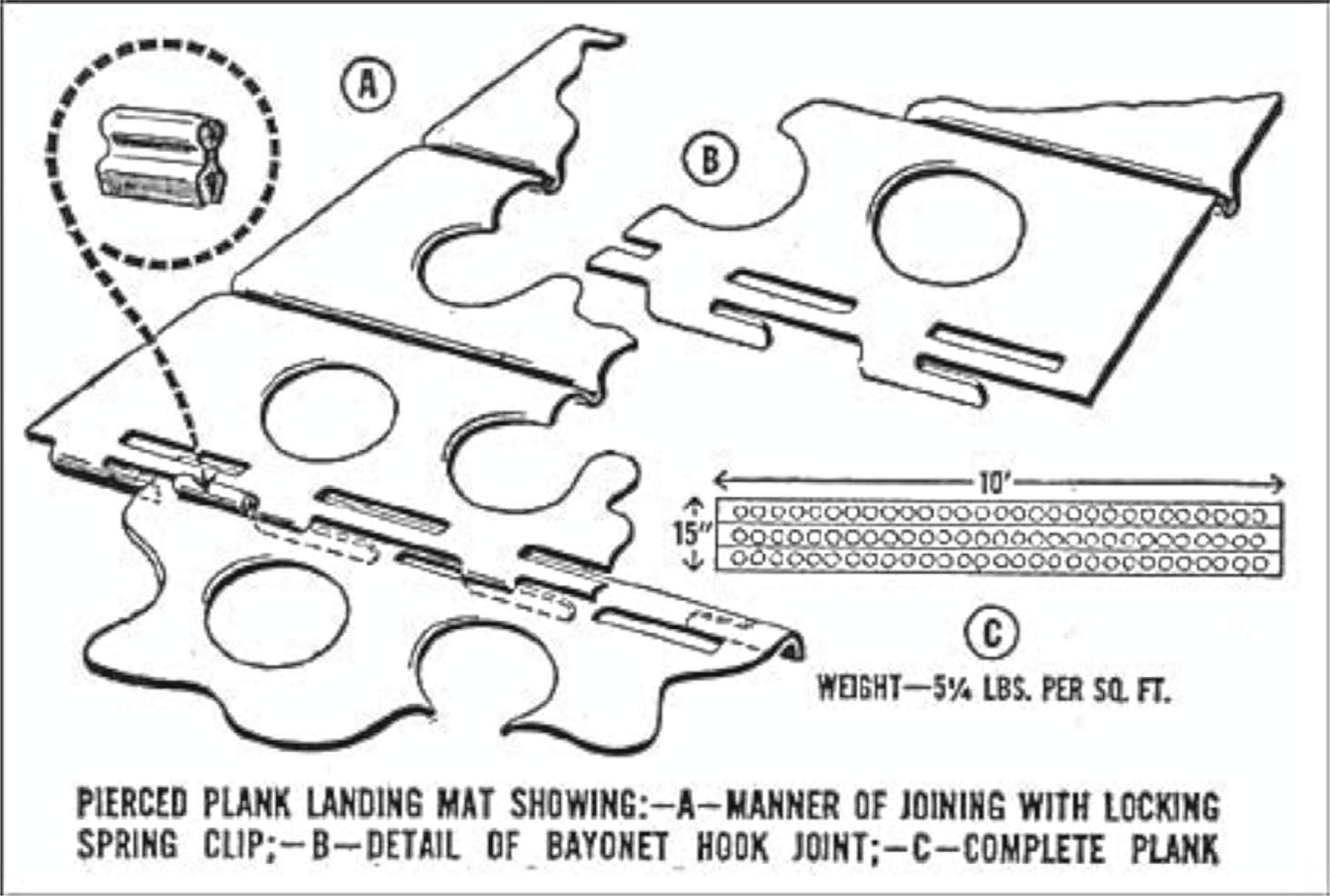

These metal mats are constructed of steel. They have holes punched through them in rows and U-shaped channels between the holes. Hooks are attached along one long edge and slots along the other, so that a number of sections can be connected (see Figure 2). The mats that we have observed in Cuba consist of single pieces with a weight of c. 65 lb (29.5 kg), a length of 3 m and a width of 0.4 m. Each mat is three holes wide and has 29 holes along its length – i.e. a total of 87 holes per mat. This is the standard type used by the US Army (Gabel 1992: 182–5).

Technical drawing of a Marston mat (National Museum of the US Air Force, file 050429-F-1234P-028, used with permission).

These standardised perforated steel mats such as those described in the previous section were originally developed by the US Army in 1941, primarily for the rapid construction of temporary runways and taxiing and landing strips (Cannon 1979: 39–43; Gabel 1992: 182–3; Cohen 1993; Mola 2014). Their official name was “PSP”, for perforated (or pierced) steel planking; the nickname “Marston mats” is a result of their first production and use at the military airfield of Camp Mackall, adjacent to the town of Marston in North Carolina. They were extremely functional, and during the Second World War these mats were used extensively to construct runways at all the US war theatres, particularly the Pacific, but also in connection with the invasion of Normandy and in Sicily (Gurney 1962; Cannon 1979: 39–43; Gabel 1992: 182–3; Mola 2014). The Marston mats were produced in various types, but the type called “M8 landing mat” was mass produced and standardised for army use (Cannon 1979: 39).

Marston mats were provided to the US’s wartime allies, including the Soviet Union, within the framework of the 1941 Lend-Lease Act (Mola 2014), by which the US supported its allies with food, oil and material until the end of the war in 1945, along with military equipment and weaponry (Allen 1955; Dawson 1959; Herring 1973; Weeks 2004). Land-lease material transported to the Soviet Union was delivered via the Arctic Convoys, the Persian Corridor and the Pacific Route (Kemp 1993). It is hard to know through which route the Marston mats were transported to the Soviet Union, but we can only conclude that they reached their destination. During the Second World War they were used in the Soviet Union for the construction of airstrips, but probably also for constructing roads and reinforcing the ground for heavy vehicles during the war on the Eastern Front, and during the march towards Berlin. During the period 1945–1962 they were used, amongst others purposes, for constructing and reinforcing roads at the strategic missile sites, and were a necessary component for the functionality of a Soviet nuclear missile base in the 1960s.

It is likely that the Marston mats of the M8 type that were shipped to Cuba were transported in August 1962 as a part of Operation Anadyr. As with the rest of the equipment bound for the strategic nuclear sites and regiments of western Cuba, they were probably unloaded in the port of Mariel, from where there they were transported by night in covered lorries to the sites of El Cacho, El Pitirre, Santa Cruz de los Pinos and La Rosa. At these sites the Soviet engineer troops used the Marston mats for reinforcing roads inside the missile sites, as well for reinforcing the ground adjacent to the launch pads (Diez Acosta 1997). Thus, they constituted necessary components for making the deadly machinery of the nuclear missile sites functional.

The agreement between the US and the Soviet Union that ended the crisis in the last days of October 1962 stated that all material constructions at the bases should be dismantled and shipped back to the Soviet Union. Due to the rapid withdrawal of the Strategic Missile Troops and the strategic nuclear missiles from Cuba that started on 31 October (Diez Acosta 2002c: 190–5), the troops had no time to recover and load the Marston mats for transport. Thus, the Marston mats were abandoned and left behind, as material memories of the road infrastructure of a nuclear missile site.

Directly after the crisis, or rather as soon as the last Soviet vehicle had left the sites of El Caco, El Pitirre and Santa Cruz de los Pinos in the first days of November, the farmers and the people from the nearby villages visited the sites looking for usable things that had been left behind. They found, for instance, boots, cans, coats, field bottles, nylon covers, oil, spades, spoons, timber boards and empty ammunition boxes. In the countryside surrounding these sites the farmers have been using material remains from the sites in different ways over the decades that have passed since the crisis; this reuse can also be found in the nearby villages (Burström et al. 2008; Burström et al. 2011, 2013; Karlsson 2017). The material that has been most commonly reused is undoubtedly the Marston mats, which have found new meanings, functions in a number of ways in new contexts (see Figure 3).

Today one can still find the Marston mats in the countryside surrounding the former missile sites, but also in the nearby villages, where they are mixed and blended with other forms of material culture. Thus, they take part in the construction of a palimpsest landscape where past and present are intimately interlaced and brought together in a manner by which these periods cannot be isolated from each other.

The photo of a Russian girl

In the Cuban countryside surrounding the former Soviet nuclear bases, cameras were not a common possession in 1962, but despite this there are a number of photographs of Soviet soldiers that various informants have showed in connection with the interviews that the project has realised with them.

The Soviet soldiers had fixed leave schedules which were followed even under the extreme conditions of the crisis. During these leaves, and in connection with duty assignments outside the bases, there existed extensive contact between them and the local Cuban population and often it was a matter of exchanging various types of goods, not least rum, in exchange for boots, watches, bread and canned goods. It also happened that contacts and friendships were made that were maintained during the crisis, but also after it in the form of an exchange of letters – contacts that lasted for years (Karlsson 2017).

In connection with the interview of Oneida Rodríguez González, during investigations related to the former missile base at El Cacho, in the province of Pinar del Río in western Cuba in 2017, she showed us a photograph that her brother received as a farewell gift from a Soviet soldier at the end of October 1962. The black and white photograph shows the Soviet soldier’s daughter who is around one year old. The girl is sitting in a wicker chair in front of a table and on the table is a bowl filled with apples. She has an apple in one hand, while she with the help of her other hand takes a bite in another (see Figure 4).

Oneida was only 8 years old when the crisis took place and her brother was around 20 years old, and it was her parents and her brother who had contact with the Soviet soldiers. The first time they came to her parents’ house, which was located just outside the base enclosure at El Cacho, it was to buy rum in exchange for their watches, but after that they returned many times to trade rum in exchange for bread and conserves, or just to talk. Her brother befriended one of them and even though the soldiers only knew a few words of Spanish they were able to understand each other with sign language and a few words. Since Oneida had no contact with the Soviet soldiers, she did not remember the name of either the Soviet soldier or of his daughter. Her brother moved to the US a few years after the crisis, but the photo remained in the house. She knew, however, that her brother had no contact with the soldier after the crisis ended and Soviet missile units left Cuba in late October and early November 1962.

It is not unusual for soldiers to take photographs of loved ones with them into the field, but their parting with these photographs voluntarily is less common. Oneida explained that the Soviet soldier only gave her brother the photograph when he was informed that they would return to the Soviet Union and then they would not see each other again. He wanted her brother and his family to have a memory of him.

Oneida was only a child during the October Crisis and six decades have passed since her brother received the photograph as a farewell gift, but even though she has long since moved from her parents’ home, she has chosen to keep it as a memory of her childhood and of the crisis. Her brother has not shown much interest in it, though.

During the interview, the photograph also brought back a series of memories for Oneida. She turned 8 in the middle of the crisis, on October 27, 1962, and she particularly remembered the US fighter planes flying at very low altitude to photograph the base at El Cacho, passing just above the roof of her parents’ home with a deafening roar. She also recalled her own and her family’s fear that war would break out at any moment, but she also remembered finding security in the knowledge that the Soviet soldiers were there to help and defend them (González Noriega and Karlsson ms).

The friendship between Oneida’s brother and the Soviet soldier, and the handing over of the photograph, is a good example of the human dimensions the project aims to highlight. Even the memories that the photograph evoked in Oneida are important parts of these dimensions. At the same time, the photograph raises a number of questions that probably cannot be answered. Today the Russian girl would be 60 or 61 years old. What is her name? Is her father still alive? Does she live herself? How was her life in the Soviet Union and later in Russia? What did she train for? Has she had a happy life? Does she have children of her own? Does she know that a photograph of her as a child is still preserved as a memory in the Cuban countryside, or that the photograph of her is used in scientific contexts? These are some of the questions of existential and human nature raised by the photograph, which somehow bring us to themes far beyond the usual stereotypical and overarching narrative of the October Crisis.

Conclusion

At the beginning of this text, two questions were presented. In answer to the first – To what extent can the dominating narration of the October Crisis be complemented and enriched by the histories of these material remains, and their specific “from below” stories? – I would like to say that the material culture and the objects presented in this text presents small-scale and material stories, as well as human histories, of the crisis that complement and enrich the dominant narrative of the crisis based in a military-strategic and Cold War perspective. As regards the second question – To the extent that this is the case, in what manner can the dominant narrative be complemented and challenged? – it can be said that the dominant narrative indeed can been complemented and challenged by the histories of the Marston mats and the photograph of the Russian girl, demonstrating that profound historical events are never as simple as stereotypical and high-level narratives often force us to believe. In this text I have approached material remains that partly tell another, and “from below”, story about the October Crisis. This implies that there is always a more complex material pattern and an intertwined story to be found beyond the dominant narrative of a historical event, and in the case of the October Crisis these complexities can be revealed by the material objects. The dominant narrative can also be complemented and challenged by the fact that more voices are starting to be heard through the efforts of the project and its interest in the material and immaterial remains from the crisis: the voices of people presenting various histories “from below” concerning their memories and experiences of the crisis.

In the Cuban countryside it is sometimes hard for some people to understand the project’s interest in the material remains, and in their memories from the crisis, but at the same time this interest in the material, and in people’s encounters with the material remains from the crisis, functions as a starting point for remembrance and for a more human dimension of the crisis. It also functions as a bridge leading to the insight that the ordinary and daily experiences of the crisis are valuable contributions to the overall knowledge and understanding of the crisis.

In the aftermath of the crisis the material objects and the memories of the crisis are now mixed and blended together in the Cuban countryside in a way that constructs a timeless palimpsest landscape and mindscape, and where material remains and memories are loaded with new meanings and functions. In this context they influence, and are influenced by, people, not least within the framework of the project presented in this text.