Introduction

International relations (IR) is an extremely multidimensional topic, with some elements having a high profile (both public and governmental) while other aspects, crucial as they might be, play out far from the mainstream currents of attention. One important sphere of activity falling into this latter category is “strategic minerals/raw materials politics”. Most people, with the exception of a few IR specialists, do not have any great or even passing familiarity with this branch of foreign policy, but those who do understand that its implications can be crucial to the domestic as well as the foreign affairs of a country.

The US government defines strategic minerals as (Hui 2021):

a mineral identified by the Secretary of the Interior to be

(i) a non-fuel mineral or mineral material essential to the economic and national security of the United States;

(ii) the supply chain of which is vulnerable to disruption; and

(iii) that serves an essential function in the manufacturing of a product, the absence of which would have significant consequences for our economy or our national security.

Currently (January 2022) there are 35 items on Washington’s list of strategic minerals, the US being self-sufficient in only three. Import reliance on the remaining 32 ranges from 17 to 100 percent, with 14 representing commodities where the US is totally reliant on foreign sources to meet its demands (CRS 2019).

Focusing on Cuba as one of those foreign sources with respect to cobalt, this article will address the following considerations:

* Cobalt as a strategic raw material

* Cuba’s status and activities as an actor in the international cobalt community

* The economic and political implications of Cuban cobalt

Within these broad parameters, particular attention will be devoted to the potential impact of the island’s cobalt reserves on its relations with the United States.

Cobalt as a Strategic Raw Material

Most Americans are not aware of the fact that Washington maintains a list of strategic minerals/raw materials and even if so, they are extremely unlikely to have any familiarity with most items that are on it. Certainly this is true of cobalt.

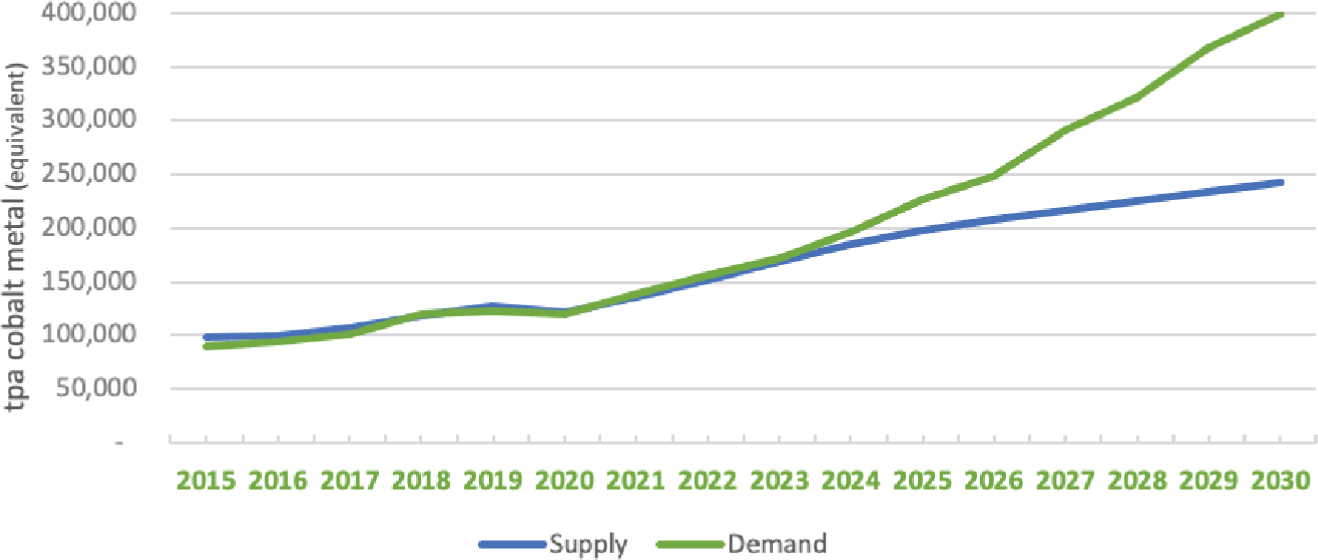

Ironically, cobalt was at one time considered a minor and therefore not a particularly valuable commodity, having a limited range of uses in some alloys and fertilizers as well as serving as a drying agent for varnishes and enamel coatings of steel. However, such is certainly not the case in the contemporary world. Why? The primary reason is the increasing use of lithium-ion batteries in such products as laptops, mobile phones and most importantly, electric-powered cars. Electric car batteries require between five and fifteen kilograms 2 of the metal, roughly a thousand times the amount in smartphone batteries. Consequently, demand for cobalt has been skyrocketing, as noted by Manuel Yepe in 2019 when he reported that “World consumption of cobalt in 2019 is estimated to be 122,000 metric tons. In 2011 it was 78,000 tons, an increase of 56% in 8 years” (Yepe 2019). Figure 1 provides an even more dramatic indication of the development of the global cobalt market, looking at the actual (and projected) supply and demand curves over a 15-year period. As of late January 2022 cobalt was selling for approximately $71,400 per metric ton, a price that should increase significantly if the supply/demand projections in Figure 1 prove to be anywhere near accurate.

Global Supply/Demand for Cobalt (per metric ton). Source: Morgan Leighton, “The Ultimate Guide to the Cobalt Market: 2021–2030,” cruxinvestor.com (January 7, 2021), available at: https://www.cruxinvestor.com/articles/the-ultimate-guide-to-the-cobalt-market-2021-2030f#toc-2.

With respect to the United States, its situation concerning cobalt as a strategic raw material is not good. As of 2020, it had reserves of just 53,000 metric tons, which represented only 0.7% of the total global figure. Consequently, as of 2020 it relied on imports for 76 percent of its cobalt consumption (USGS 2021), the rest being covered by limited domestic production and recycling. Moreover, and this is very important, Washington lists cobalt as having the third highest supply chain risk on its list of strategic minerals (Federal Register, 86(237) (2021), 71085). Yet despite these problems, the US has aspirations, deeply rooted in its commitment to shift from fossil fuels to electric power in the automotive and other industries, to become a major player in the production of lithium-ion batteries. The Tesla company, for example, has built a giant factory in Nevada which it expects to become one of the largest lithium-ion battery manufacturing facilities in the world, with other US companies poised to follow in its footsteps. All of these factors, however, generate major challenges for the US related to cobalt. Specifically, when one considers the country’s very limited domestic production capabilities and the ambitious manufacturing plans for lithium-ion batteries by Tesla and other major automakers, the obvious conclusion is that the United States will need major assistance from other countries if it expects to be able to meet its projected demand for cobalt.

A complicating factor with respect to cobalt as a strategic resource for the US lies in the fact that it is one of the six minerals on Washington’s list that is a “by-product material”, which means that it cannot be mined separately, but rather is acquired only as a result of the mining of another mineral. In cobalt’s case, it is a by-product of nickel and to a much lesser extent copper mining. The Congressional Research Service explains the conundrum involved with such by-products as follows (Humphries 2019: 13):

Byproduct supply is limited by the output of the main product. As production of the main product continues, the byproduct supply may be constrained because a higher price of the byproduct does not increase its supply in the immediate term. Even in the long run, the amount of byproduct that can be economically extracted from the ore is limited. That is, byproduct supply is relatively inelastic (i.e., not particularly responsive to price increases of the byproduct). For byproducts, it is the price of the main product, not the byproduct, that stimulates efforts to increase supply.

In short, the production of by-products such as cobalt does not necessarily respond to the normal dynamics of supply and demand. It therefore may be important in these cases for a particular customer (e.g. the United States) to be able to draw upon multiple major suppliers to meet its demands. It is here that Cuba comes into the picture.

Cuban Cobalt: An Overview

The countries with the highest reserves of cobalt are summarized in Table 1. Obviously the supply choices here for the United States are rather limited, with Canada being the only country where there are no problems or potential issues. The Congo, for example, has long been plagued by corruption and political volatility. Shipping costs are likely to be a downside with regard to Australia as well as the Philippines and clearly it is unlikely that Washington would want to become too dependent on Russia as a supplier. Cuba, therefore, stands out as the “wild card” in the whole group; its reserves are substantial and only Canada promises lower shipping costs. But casting a long shadow over the potential relationship is U.S sanctions policy which severely restricts, and in most cases forbids, commercial trade with the island.

Of all of Washington’s active sanctions programmes, Cuba holds the dubious distinction for longevity. The first measures were imposed in early 1962 by the Kennedy administration and since then have grown into an extremely complex (and potentially confusing) mixture involving such elements as congressional legislation, presidential executive orders and bureaucratic regulations. 3 The most comprehensive compendium can be found in the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 31, Section 515.204, where, with respect to the question of importing Cuban goods, the general principle is laid down that:

Except as specifically authorized by the Secretary of the Treasury (or any person, agency, or instrumentality designated by him) by means of regulations, rulings, instructions, licenses, or otherwise [italics added], no person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States may purchase, transport, import, or otherwise deal in or engage in any transaction with respect to any merchandise outside the United States if such merchandise: (1) Is of Cuban origin; or (2) Is or has been located in or transported from or through Cuba; or (3) Is made or derived in whole or in part of any article which is the growth, produce or manufacture of Cuba. (Code of Federal Regulations 2011)

Subsections (1) and (3) would seem to suggest that no imports into the US from Cuba are allowed and indeed for many years such was essentially the case, especially with regard to basic commercial products. However, the italicized material above provides for exceptions to this general rule. One mechanism by which this can occur involves the exercise of the President’s executive powers. One important example of this phenomenon occurred in the waning days of the Obama administration when the departments of Treasury and Commerce, acting under the auspices of the President’s policy directive seeking to promote better relations with the island, announced some major changes on 14 October 2016 which provided the opportunity for Cuban pharmaceuticals to enter the US market, an opportunity first seized upon by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute of Buffalo which entered into a joint venture agreement with a Cuban partner that provided for cooperation in research, manufacturing and the eventual marketing of Cuban drugs in the United States (Erisman 2021). But Cuban cobalt, despite its status as a strategic mineral, has not been accorded similar consideration.

The island’s primary source of cobalt is the nickel mine at Moa, located in Holguín province. The Moa operation is a joint venture undertaking between Sherritt International of Canada (50 percent) and the General Nickel Company of Cuba (50 percent). Combined with a Sherritt refinery in Canada, this facility produces15 percent of the world’s cobalt with an extremely high purity rate of 99.98 percent. Other regions across Cuba where there may be commercially viable nickel-cobalt deposits include Mayarí, San Felipe and Cajálbana.

The Moa reserves have a rather complicated history. Focusing only on the highlights thereof, initial development took place during World War II by the United States in order to strengthen the nation’s nickel-cobalt supply line. A company named the Moa Bay Nickel Company, which was a subsidiary of the Freeport Sulphur Company, was established during the war with Washington providing $100 million of the total $119 million start-up costs, with the rest coming from Freeport. Freeport then ran the operation under a contract with the United States Government until its closing in 1947 as an uneconomic enterprise. In 1957 Moa Bay Mining, a Cuba-based subsidiary of Cuban American Nickel Company, reached an agreement with the US government to undertake further development of the Moa mine which had been rehabilitated and reopened in the early 1950s. Ultimately, however, this involvement by Washington and various US companies in the Moa reserves would come to a screeching halt when Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government seized control of the Moa operations in 1960 (Estainlesssteel n.d.).

The next and current development in Moa’s odyssey occurred in late 1994 when Sherritt International, a Canadian multinational corporation, entered into a 50/50 joint venture extraction/distribution agreement with the Cuban government regarding the Moa reserves. Sherritt does the mining and initial processing at Moa and then ships the ore to its refinery/distribution facility in Fort Saskatchewan (Alberta). According to the agreement, Sherritt is allowed to repatriate a fixed level of the profits involved while also being required to reinvest a percentage in Cuba. This reinvestment proviso has resulted in Sherritt becoming involved in such non-mining sectors of the island’s economy as oil and gas production and power generation.

As of late 2021, Sherritt was making plans to both increase production at Moa and to take steps to lengthen the life of the mine, whose stockpile of nickel was estimated in 2021 at 5.5 million tons of proven reserves (thus ranking Cuba number 5 in the world in terms of proven nickel reserves). The life span estimate for Moa is approximately 20 years at current production rates, with the island’s probable overall reserves (estimated at 2.2 billion tons) adding another 50–5 years to that figure. Thus, it would appear that Cuba’s nickel-cobalt production prospects will remain solid well into the 21st century.

Like many other companies that do business with Cuba or wish to do so, Sherritt has had to confront, and has been adversely affected by, the draconian sanctions that Washington imposes on Cuba, and in many cases by extension to the island’s economic partners. A good example of this phenomenon occurred in 2018 with respect to Sherritt’s Cuban cobalt and its relations with Panasonic. US sanctions forbid companies from engaging in economic transactions which result in goods entering the US which contain even the slightest trace of Cuban materials. Companies that run afoul of this prohibition, whether domestic or foreign, become vulnerable to various penalties that can be imposed by Washington. In Sherritt’s case, problems arose with respect to cobalt from Moa that it sold to the Japanese electronics giant Panasonic. Panasonic produces a wide range of products, including lithium-ion batteries for which it is the sole supplier to Tesla, the US electric car manufacturer. The problem was that Panasonic’s Cuban cobalt was intermingled with that from other sources. As such it was possible that the batteries that Tesla procured from Panasonic contained some cobalt from Moa. Faced with potential Helms-Burton penalties, Panasonic withdrew from its business relations with Sherritt. This was not only an economic blow to Sherritt, but also to Cuba which, as Sherritt’s partner in the Moa operations, lost 50 percent of the potential profits from sales to Panasonic.

The Sherritt/Panasonic episode is a perfect example of what many consider to be the dysfunctional nature of such US sanctions. In both business and diplomacy, the ideal outcome is to create a win/win situation. This case, on the other hand, is symptomatic of what is in most instances the result of Washington’s sanctions policy toward Cuba – nobody wins. Sherritt and Havana have lost an important customer along with the income involved; Panasonic has lost a key component in its cobalt supply chain; and the United States has isolated itself from a major and very convenient source of one of the most important items on its strategic minerals list. In short, what one sees here is a classic illustration of a lose/lose situation. However, looking at the larger picture, what are the economic and political implications for Cuba of its cobalt reserves?

Cuban Cobalt: Economic and Political Implications

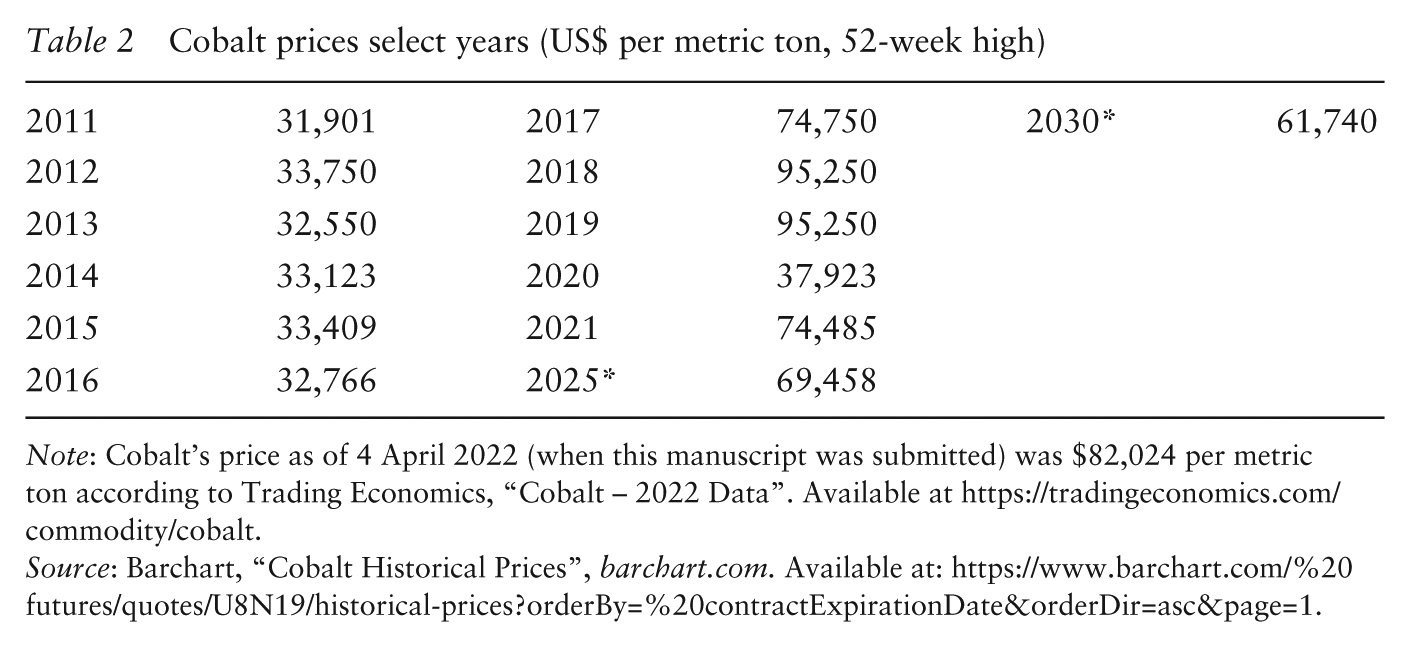

Recognizing that production/price forecasting can be precarious in the often volatile world of the mineral business, cobalt’s long-term economic implications for Cuba nevertheless look to be quite positive. Table 2 provides an overview of cobalt’s pricing patterns over recent years, along with estimates of future trends (marked with an asterisk) through 2030.

Cobalt prices select years (US\(per metric ton, 52-week high)

Note: Cobalt’s price as of 4 April 2022 (when this manuscript was submitted) was \)82,024 per metric ton according to Trading Economics, “Cobalt – 2022 Data”. Available at https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/cobalt.

Source: Barchart, “Cobalt Historical Prices”, barchart.com. Available at: https://www.barchart.com/%20futures/quotes/U8N19/historical-prices?orderBy=%20contractExpirationDate&orderDir=asc&page=1.

The rather drastic slump in cobalt prices noted in Table 3 for the 2018–20 period was a function of the COVID-19 pandemic’s negative economic impact on countries and international trade throughout the world. The industry appears, however, to have recovered fairly quickly and is projected to resume the upward price spiral that has characterized it since 2011.

Cobalt’s actual, and especially its potential, economic impact on Cuba is rather obvious, particularly with respect to Havana’s ability to gain access to hard currency. Like most other relatively small islands, Cuba is heavily dependent on imports for many of its basic necessities, with hard currency usually being needed to finance them. In recent years Havana has acquired such hard currency via three main mechanisms: tourism revenues, remittances sent by overseas Cubans and medical services supplied to various countries. The problem is that two of these three sources are not terribly reliable with respect to their sustained growth potential, due to a great extent to Washington’s economic sanctions. The main potential bull market for Cuban tourism is the United States, which came into play for a brief period during the latter part of the Obama administration when travel restrictions were relaxed as part of the President’s attempts to improve/normalize relations with Havana. Consequently, the number of Americans visiting the island (and thereby generating tourism revenues) rose from 63,000 in 2010 to a peak of 638,000 in 2018. Subsequently, however, the Trump administration not only reinstated but also enhanced the restrictions, resulting in only 58,000 US visitors by 2020 (Statista n.d.). A similar pattern characterized remittances which the US Cuban-American community was allowed to send to relatives on the island, although it is difficult to provide exact figures since only varying estimates are available (Delgado Vázquez 2021). Because the Biden administration has maintained these Trump policies, US sanctions remain an obstacle that Cuba faces in its efforts to acquire hard currency.

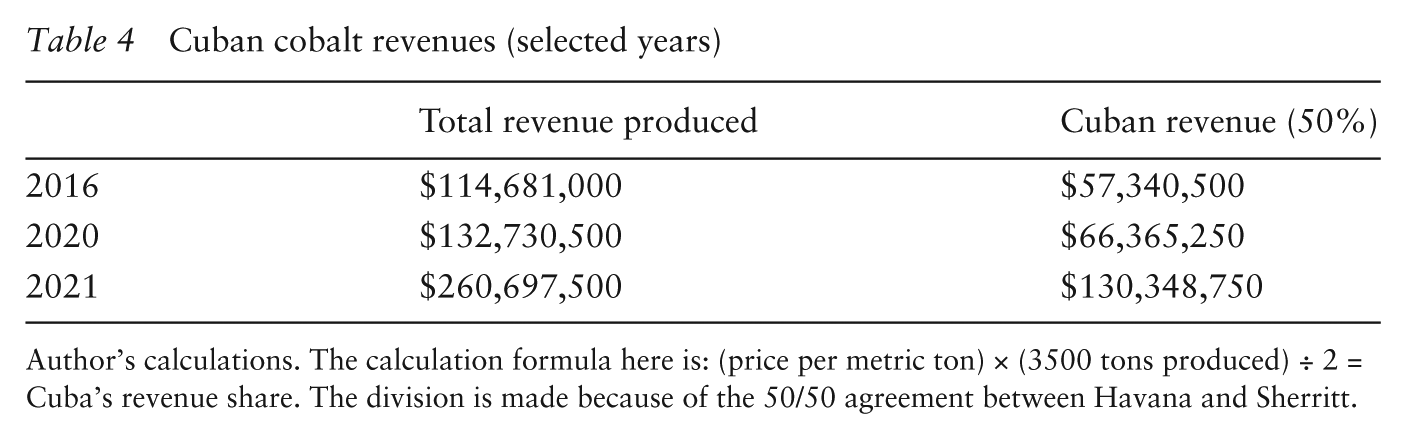

Cobalt, however, has the potential to mitigate somewhat these sanctions problems. Cuban production during the 2018–2021 period held steady at about 3,500–3,600 tons per year. Table 4 provides some illustrative figures for Havana’s annual cobalt revenue using Table 2 prices per metric ton and a constant 3,500-ton annual production rate. Granted, the high figure of \)130 million plus comes nowhere near the revenues produced by medical services, remittances or (in its good years) tourism, which routinely ran into the billions. Nevertheless, $130 million still represents a significant contribution of hard currency to the Cuban economy which will help to finance the imports which are crucial to the well-being of the island’s society and its people.

Cuban cobalt revenues (selected years)

Author’s calculations. The calculation formula here is: (price per metric ton) × (3500 tons produced) ÷ 2 = Cuba’s revenue share. The division is made because of the 50/50 agreement between Havana and Sherritt.

As was dramatically and tragically demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020, any major interruption of the revenue inflow from these four primary sources can be economically devastating for Havana. Even though Cuba, using its homemade vaccines, was among the more successful countries in combating public health dangers posed by COVID-19, it could not escape the economic chaos accompanying the virus. Havana’s Economics Minister summarized the 2020–1 situation as follows: the island’s economy lost more than $3 billion, the result being a 13 percent decrease in its Gross Domestic Product (OnCubaNews 2021). The result for the average citizen was shortages in crucial items for everyday living such as food, petroleum, electricity, medicines, etc. If, however, one projects beyond the COVID crisis, cobalt’s potential contribution to Cuba’s hard currency reserves looks quite promising. For example, if one takes its 198.5 percent price increase over the pre-COVID years (2011–18) noted in Table 3, and applies that over a similar seven-year period to Cuba’s 2021 cobalt revenues noted in Table 4, then one can project revenues of $258,872,618 for 2028, which obviously would not be an insignificant contribution to the island’s economy.

However, as suggested in the title of this piece, it may very well be that cobalt’s greatest impact on Cuba’s future well-being will flow from the crucial role that it could play should Havana prove willing and able to engage in strategic mineral politics with the United States. Referring back to the previous section on “cobalt as a strategic raw material”, the US finds itself in a highly unfavorable and vulnerable position with respect to a mineral that is crucial to electric vehicles that are poised to dominate the automotive industry. The US has no significant cobalt reserves, and hence has to import 75 percent of its requirements within the context of a situation wherein Washington lists cobalt as having the third highest supply chain risk on its list of strategic minerals. Cuba, with the third largest reserves in the world and no industries which create a large domestic demand for cobalt, obviously could help to alleviate the US cobalt problem (an additional benefit being the lower shipping costs compared to other potential suppliers – see Table 1). The major problem with this scenario is, of course, Washington’s long-term policy of restricting trade, both direct and indirect, with the island.

Even so, as noted previously, the US trade blockade is not ironclad. The President has considerable latitude through the office’s executive powers to modify the sanctions, either relaxing or strengthening them. President Obama, for example, pursued a course of moderation in his attempt to improve relations with Cuba. Travel restrictions were loosened, resulting in a veritable tsunami of American visitors spending vast amounts of US dollars. Also, changes were made that opened access to the US market for Cuban pharmaceuticals. Later the Trump administration would not only roll back some of Obama’s trade reforms (the pharmaceutical provisions being the main exception), but also would wield its executive powers to strengthen and expand the sanctions regime.

The above actions regarding the American economic blockade were undertaken as essentially unilateral initiatives. However, since cobalt is a highly desirable strategic raw material for the US that has a very high degree of supply chain risk, a very rational position for Havana to take would be to insist that any change in cobalt’s sanctions status and therefore its availability to the US take place within the context of bilateral negotiations. In other words, Cuba could play the strategic minerals politics card. Despite the long history of suspicion and animosity between the two governments, serious and productive bilateral negotiations have occurred when both parties have seen mutual interests and benefits involved (LeoGrande and Kornbluh 2015). Usually such negotiations, especially those that have produced an agreement, have focused on a single issue (e.g. drug trafficking). But in some instances it might be possible for a negotiating party (e.g. Cuba) to engage in what diplomats call “linkage”, which simply means that issues that are not part of the main focus of discussions are laid on the table. An example would be where two parties are meeting to discuss their economic relations, but then one party wants to add to the agenda the other country’s military ties to a third party. Washington routinely resorted to such linkage during the Cold War, insisting (without success) that Havana cut its military ties to Moscow as the price for improved economic relations with the United States. With respect to cobalt, however, the tables appear to be turned, with Havana enjoying the stronger negotiating position, and thus able to explore the possibility of linkage within a context of strategic minerals politics.

If the above analysis is correct, the question for Havana then becomes what items to link in any cobalt negotiations with Washington. Ideally Cuba would like to see the total abandonment of the US economic blockade, but that is not terribly feasible given that control over significant elements of the sanctions regime rests with Congress and therefore cannot be changed via presidential executive orders. As such, Havana would have to choose what issues to link. Among the negotiating possibilities which come to mind that would markedly help the Cuban economy (especially with respect to the inflow of hard currency) are a complete lifting, or at least a severe limitation of restrictions on

* travel to Cuba by US citizens

* remittances sent by Cuban-Americans to relatives on the island

* development and marketing of Cuban petroleum reserves

* doing business with Cuban companies where the Cuban military is involved

The above list contains two of the three most profitable sectors of the island’s pre-COVID international economic relations (travel/tourism and remittances, both involving hard currency), the other being revenue generated by medical services that Havana provides to a wide variety of nations. With respect to the third item above (petroleum), Cuba must rely on imports for approximately two-thirds of its total consumption. However, beginning in 2008 various geological explorations began to indicate that there are massive deposits north of the island in its offshore exclusive economic zone, the estimates running from 7 to 20 billion barrels. The latter figure, if correct, would be sufficient to meet Cuba’s domestics needs for at least 100 years, with large amounts left over for (hard currency) export. But there is a serious problem in that there are major engineering challenges involved in extracting the oil and much of the state-of-the-art technology available to overcome them is under US authority and hence cannot be used due to Washington’s sanctions (Erisman 2019). The final item on the list, which came into play during the Trump administration and has been maintained by President Biden, impacts and intensifies all of the others. In June 2017 the White House announced new restrictions on economic relations with Cuba, declaring that:

(a) no person subject to U.S. jurisdiction may engage in a direct financial transaction with any person that the Secretary of State has identified as an entity or subentity that is under the control of, or acts for or on behalf of, the Cuban military, intelligence, or security services or personnel and with which direct financial transactions would disproportionately benefit such services or personnel at the expense of the Cuban people or private enterprise in Cuba. (OFAC 2017)

The above provisions represented a tightening of US trade sanctions, since Havana’s armed forces personnel (both active and retired) are involved in one way or another with the operation of various enterprises within the island’s economy. 4 This phenomenon is not unusual in many countries such as Cuba that are seeking to achieve some significant economic progress, since the military is often a prime source of people with the high-level technical and managerial skills that are required in order for key sectors of a developing economy to function effectively. A good example of the negative impact of the sanction can be seen when considering the travel issue. Even if other restrictions limiting visits by US citizens were lifted, the prohibition on doing business with entities under the control of, or acting on behalf of, the Cuban military would still represent a major deterrent to the average citizen interested in going to Cuba. Why? Most casual travellers are in a “tourism mode” whereby they prefer the convenience and amenities of the large commercial hotels and resorts. In Cuba military-controlled firms are concentrated in the tourism sector and thereby are involved in managing practically all such facilities. 5 Consequently US travellers must find alternative lodging, the main option being small “bed and breakfast” operations in private homes (called casas particulares) which usually have a very limited number of rooms available and in some instances may be difficult to find and to make reservations. Thus, when confronted with such complications along with the threat of legal action by US authorities if they run afoul of Washington’s restrictions, American travellers may choose to bypass Cuba and take their business elsewhere. Due to its broad scope that potentially affects a wide range of economic activities (including remittances and petroleum as well as travel), Havana could be expected to give the “no military” sanction top priority in any linkage that it might try to introduce into strategic mineral politics involving cobalt.

Conclusion

The cobalt question provides a fascinating look into one of the more esoteric dimensions of the US/Cuban relationship. The conventional view thereof is that tensions and animosities that have characterized the relationship for more than 60 years have become so embedded in the psychology of the relationship, particularly on Washington’s part, that there is little sentiment for, or prospect of, any significant cooperation or improvement. There is some validity to this viewpoint. However, as noted previously, exceptions can occur when there are mutual benefits involved. In this instance, an agreement making Cuban cobalt available could serve to address both one of Washington’s high priority strategic mineral concerns, and Havana’s need for enhanced economic relations in general and hard currency revenues in particular.

Summarizing the preceding material, what is unusual in this instance is that Cuba appears to enjoy the stronger bargaining position, especially when one considers that foreign policymakers tend to be strongly influenced by the realist school of international affairs. This perspective stresses the need to give top priority to a country’s national security/strategic interests. Cobalt would appear to fall into this category for the US, as evidenced not only by the simple fact that Washington includes it in its list of strategic minerals, but also that it ranks quite high in the three criteria (see this article’s Introduction section) which determine whether a mineral qualifies for that list. Such is not the case for Cuba; cobalt is not a crucial input for any of the island’s domestic industries and there will always be other customers for it. Admittedly there are, as noted in Table 1, alternative sources from which the US could acquire cobalt, but Cuba enjoys certain advantages which make it more attractive than other potential suppliers. Taking all of the above elements into consideration certainly suggests that Havana’s bargaining position would be quite strong in any discussions about a US/Cuba cobalt agreement, thus opening the door for Havana to interject linkage into the negotiating process by demanding concessions from Washington on some of the economic sanctions that it continues to impose on the island.

In the final analysis, then, it is possible that Cuban cobalt and the strategic minerals politics surrounding it might serve as a vehicle to rejuvenate the efforts most recently undertaken by the Obama administration to establish a more normalized relationship between these two traditional antagonists. In other words, if Havana demonstrates a willingness to take action (i.e, providing cobalt to the US) which serves to promote Washington’s strategic mineral interests, and the US reciprocates by significantly reducing or even abandoning some of its onerous economic sanctions on the island, a process of serious “confidence-building” could be set into motion. James Macintosh summarizes this concept as follows (Macintosh 1996: vii):

Confidence building, according to the transformation view, is a distinct activity undertaken by policy makers with the minimum intention of improving some aspects of a traditionally antagonistic … relationship through … policy coordination and cooperation. It entails the comprehensive process of exploring, negotiating, and then implementing tailored measures, including those that promote interaction, information exchange, and constraint. It also entails the development and use of both formal and informal practices and principles associated with the cooperative development of CBMs [Confidence Building Measures]. When conditions are supportive, the confidence building process can facilitate, focus, synchronize, amplify, and generally structure the potential for a significant positive transformation in the relations of participating states.

In other words, confidence-building measures can generate a long-term spillover effect into other broader policy areas, resulting in a dramatic transformation in the relations between two countries, which in the case of the US and Cuba could lead to moderation or perhaps even the complete abandonment by Washington of its sanctions against the island. Even if the confidence-building scenario does not play out exactly as described by Macintosh, cobalt is an issue area where the interests of both governments clearly coincide. Therefore, like the existing agreements on migration and counter-narcotics, there is room for progress that could function to improve the overall atmosphere of the relationship. In other words, the rationale for reaching an agreement (even without any spillover) is that it would in itself be good for both countries, producing a win/win situation which is the essence of normal diplomacy.

There is, of course, no guarantee that cobalt (or anything else) will prove capable of exerting this kind of impact on a sanctions policy that Washington has doggedly pursued for 60+ years despite the fact that it has not come anywhere near to achieving its ultimate goal of forcing regime change on the island. Instead, the best that the sanctions have occasionally been able to produce is an ignoble scenario of economic hardship for the Cuban people. Should cobalt-based strategic mineral politics prove effective in helping to interject some normalisation into this mutually corrosive relationship, it would not only be in the best interests of the two governments involved, but perhaps more importantly, in the best interests of the citizens of both countries.