Introduction

The history of Cuba is deeply intertwined with the history of empires and power struggles, a centrepiece in the existence of the modern world. As a result of massive flows of population, commerce and cultural influences, Cuba’s identity is in essence a synthesis of a wide array of components of different origins, that interacted to create emerging properties, to build multi-layered imaginaries and to set a specific tempo for its evolution.

Since the second half of the 19th century, that history has been the story of Cuban nationhood; more precisely, the process of defining a nation, building its core institutions, obtaining its independence and protecting its sovereignty. All political movements and all major political events have included the centrality of Cuba’s sovereignty, either as the goal of the actors involved, or as currency in a bargain for a domestic power position subordinated to a foreign dominant polity.

For over a century, the main external actor in Cuba’s history has been the United States. As the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere, the North American country became a looming presence in the island’s economy decades prior to the beginning of the Cuban independence wars. After 1880 the United States became Cuba’s economic metropolis (Perez Jr. 1983; Le Riverend 1974: 508). It gained influence in the island’s political affairs and, eventually, as a result of the Cuban-Spanish-American War of 1898, it took control of the country. This was the first and most basic stone in the foundation of its regional power structure, and in turn was a central pillar of its subsequent standing as a global player.

The Revolution of 1959 – like all previous revolutionary movements – aimed at building Cuba’s sovereignty, along with a deep transformation of its social, economic and political structures. The accumulated evidence is clear in this sense: the socio-political structure and the independence–dependence dichotomy were fully integrated at the very core of Cuban history, hence the impossibility of having sovereignty without social transformation. Conversely, all subsequent attempts by Washington to reclaim its influence over the country have inevitably had the goal of creating a political and social regime in Cuba that fits the description of junior partner in an asymmetric relation (Dominguez Lopez & Yaffe 2017). This continues to be the case for all the ongoing current attempts.

It seems evident, therefore, that Washington’s Cuba policy must be a major dimension in any analytical model that we may apply to the island’s history, inasmuch as it is a factor that affects its politics, economy, culture and society. Hence the interest of studying the variables that drive that policy, and the forms that the policy takes.

The aim of the discussion that follows is to contribute to the understanding of that policy. This is not only essential for understanding Cuban history, but also it is an important issue in United States’ politics and political history that should not be underestimated. In this text we aim to explain the policy toward Cuba made in Washington in the early 21st century, that is, between the inauguration of George W. Bush as president and the first year of the Joe Biden administration. We focus attention on the long-lasting trends and the variables that shape the US Cuba policy, and then we explore the main expressions that those policies take.

In our view, foreign policy is a set of policies made by state and non-state actors in relation to other foreign state and non-state actors. Here we are addressing a subset of the foreign policy of the United States. We consider that a state’s foreign policy is, by definition, a type of public policy, in line with the view of González Gómez (1990). A public policy can be defined as any action or inaction decided by a government in any specific policy area (Dye 2017: 3). In our study, we use the theoretical framework proposed by Dominguez Lopez and Barrera Rodriguez (2020), derived from cyclical models of policy making synthesised by Dye (2017) and Birkland (2015).

There are three key additions to the cyclical model. First, the role played by other governmental actors, as any organ making policy is part of the system of government, which in turn is part of the political system, which in turn is part of the cultural complexus that is the society at large, a multifaceted, dynamic, adaptive system (Dominguez Lopez 2020: see Figure 1). The second derives from this systemic nature: the role of non-governmental actors, organised or not, largely controlled by the elites, given their demonstrated influence on the political process (Gilens & Page 2014). The elites are not monolithic, as the views and interests of different power groups and individuals shape political competition, despite their consensus on overarching matters (Govea Gorpinchenko & Domínguez López 2020).

The third addition is the importance of state policy which establishes the general orientation, strategic goals and acceptable range of variation for specific public policies. This is an important concept, frequently used but seldom defined, a reality that creates a relatively diffuse notional space with ample room for competing and sometimes contradictory approaches. It is interesting that Bobbio and Matteucci did not offer a definition in their otherwise extensive and important Dictionary of Politics (Bobbio & Matteucci 1976). For their model, Dominguez Lopez and Barrera Rodriguez (2020: 178) defined state policy as “the general framework of policies on an issue or group of issues generated by the relative and dynamic political consensus among groups of power that extends beyond the limits of an administration or the dominance of one political force.” Figure 1 encapsulates the resulting model.

In our discussion, we use official documents produced by the US government, a wide array of academic works, publications by different media outlets and information obtained from Cuban official sources.

Variables in the US Cuba Policy in the 21st Century

From the model briefly presented above, it follows that the variables that drive the process of policy-making form a complex dynamic system, are interdependent and that their relative weights change over time. The same is true for the US Cuba policy.

We identified three sets of variables. The first is the structural variables, whose values persist for longer periods and which create a relatively stable framework for concrete policies. These act as parameters in a given time period, due to their very slow change. These are the main source of the State policy.

There are two fundamental components of this set of variables: the national project of the US, and the geopolitical value of Cuba. The first is basically the guideline for the United States’ projection as an international actor. If we consider the role and nature of the elites (Mills 1956; Domhoff 2006; Govea Gorpinchenko & Dominguez Lopez 2020) and their role in the policy-making (Domhoff 1990; Gilens & Page 2014), it follows that the national project is driven by a broad consensus of the elites. Their control of the mechanisms of reproduction of consensus and formation of public opinion lead to the insertion of that project into the public’s imaginary, thus producing legal legitimacy (Weber 1971: 170–180) to reproduce the social and political structures.

A clear view of this can be derived from the Monroe Doctrine (Monroe 1823), and its interpretation in the Roosevelt Corollary (Roosevelt 1904). These two documents show that from the early times of the United States, its elites asserted the importance and necessity of securing a stable base and a power structure in the hemisphere. This was particularly the case for the Great Caribbean Basin – the combined basins of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico – to not allow the presence of external powers. If we relate this to John L. O’Sullivan’s Manifest Destiny, a document with clear messianic connotations (Engdahl 2018; Mountjoy 2009), it follows that this policy was consistent with an ideological vision of a predestined dominant role for the United States.

This project translated into a long sequence of direct military actions to control the new states in the Great Caribbean Basin, with years-long occupations of Cuba, Nicaragua and Haiti (Salazar Torreon & Plagakis 2021). In parallel, in the 1880s Washington launched the Pan-American project, the first attempt to create a regional institutional structure under its control (Connell-Smith 1966). These actions were interlocked with economic policies and the activity of companies that subordinated the region through a system of unequal treaties, enclave economies and the association with local political and economic elites (Prieto Rozos 2014; Ayerbe 2012; Bulmer-Thomas 2010). The transformation of the international system that followed World War II opened a new scenario for Washington, one in which its influence could expand globally.

Therefore, as the evidence from history and key documents shows, the national project of the United States, basically since its inception, was to build a power capable of projecting influence beyond its borders, using the Great Caribbean Basin, and eventually to become the hegemonic global power. What we observe is a process of empire building, often presented as the right and/or duty of the US to lead the world, an expression that often enters the public discourse, including into the lexicon of common people.

The geopolitical value of Cuba stems from its geographical location at the centre of the Great Caribbean Basin. The building of colonial empires in the Americas was a primordial component of the expansion of European powers, which was a driving force in the development of capitalism. Cuba was a node in a growing network that brought with it the Atlantic system connecting Africa, Europe and the Americas (Bailyn & Denault 2009; McClusker 1997; Morgan 2014). This in turn was a zone of contention among major powers, as the hemisphere was in fact a hub connecting trade routes and distant parts of the emerging world-system (Yun Casalilla 2019). This historical development was fuelled since the dawn of the early 20th century by the growth of the US economy, the opening of the Panama Canal, the insertion into the world economy of a series of key strategic resources located in Central and South America, and the fact that most of the international trade in goods was still carried by sea and along routes similar to those that had developed since early modern times. 3 Hence, Cuba is at the core of a network of routes and key nodes, a position of geo-economic and geostrategic significance.

The development of the United States as a regional and global power added an extra layer. To Washington, the Great Caribbean Basin was both a frontier and a core component of its national security zone. It is true, as their national security strategies demonstrate, that national security for the United States elites is not only about the country’s territory and population, but about their interests as far as they reach (President of the United States 2002, 2006, 2010, 2015, 2017a, 2021). Yet, the Caribbean region combines the centrality of their territorial and broader interests. That placed Cuba among the first targets of US foreign policy.

Documents and speeches by several of the founding fathers, along with other texts and actions, show that acquiring control of the island was considered both a need for the survival of the American Republic, and a right stemming from nature, predestination and politics (Perez 2014). The history of both countries, the region and the world introduced other factors and nuances, yet the geopolitical value of Cuba remained.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 created a fracture in the hemispheric power structure, by taking the island country out of Washington’s control. This appeared to be an opportunity for rival powers, as well as a source of support for revolutionary movements in the hemisphere. Even in very recent years, American specialists insisted on the geopolitical relevance of Cuba in the 21st century (Feinberg 2020).

The second set is what we call contextual variables. These are variables that describe the boundary conditions that are significant to the actions of the US policy makers regarding Cuba. We can divide these into three main components: the balance of forces in the international system, the situation in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the situation in Cuba itself. The influence of these variables is qualified by the perception of specialists, government officials and members of the elites.

In the first two decades of the 21st century, the international system witnessed the decline of US hegemony, also called the crisis of US leadership, in the global system (Bulmer-Thomas 2018; Maier 2006; Bacevich 2002; Kennedy 1987). The debate about this decline took centre stage after 11 September 2001, the war on terrorism, the 2008 financial crises and the rise of China as economic competitor. This sequence of events converged with concomitant social and political crises, that involved rapidly growing inequality, the decline of the middle class and a surge of right-wing populism and political polarisation (Dominguez Lopez & Barrera Rodriguez 2018).

The limits of the American power became more visible with the convergence of three interlocked processes. First, the re-emergence of Russia as a major international actor. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow looked for a place in the post-Cold War international system, initially trying to build an alliance with United States. This bid failed due to multiple reasons, including Washington’s attitude towards the Eurasian country. The ascension of Vladimir Putin to the presidency, the recovery of the Russian economy and a comprehensive policy of reinvigoration of the country, relaunched it as a global player. This led to increasing frictions that eventually became an open confrontation, when Moscow showed its capacity and will to act on its own interests even in opposition to the United States (Dominguez Lopez & Borges Pías 2016).

Second, the emergence of China and its capacity to compete with and surpass the United States in the economic and technological spheres. The growth of its GDP (Morrison 2019) and its advances in core technologies like artificial intelligence, nuclear fusion, renewable energies (Wang et al. 2019) and telecommunications (Inkster 2019), put the Asian giant on the path to take the lead in the global economy. Beijing also demonstrated its intent to be more active in the international arena, with its Belt and Road Initiative, its reinforced military capabilities and the strengthening of its position in a series of international disputes (Turcsányi 2018)

Third, the formation of the China–Russia strategic alliance. These were two major nuclear powers, the second and third largest military powers – and leaders in some categories – two countries with massive natural and human resources, and strong scientific potential. Their association was clearly oriented to counterbalance the influence of United States in the international system. The creation of the Cooperation Organisation of Shanghai added an extra layer to the alliance, when it attracted, in one or other capacity, several important international actors like India, Iran, Pakistan and Kazakhstan, regional powers in their own rights, some with an antagonistic relation with United States (Gorodetsky 2003: 142–50)

US ruling elites recognised the ongoing global power shift as one of its main foreign policy challenges. Despite the diversity of views, both parties and all administrations during the period worried that the growing influence of countries such as China and Russia would be a trend that had the potential to reshape the global order to the detriment of Washington’s hegemonic position (President of the United States 2015, 2017a, 2021). Consequently, they strove to reinforce the status quo, and to reorient the dispute to advance their interest as the natural hegemon based on “American exceptionalism” and the idea that a United States-led world order is indispensable for stability. Therefore, any challenge to that order generated a reaction. Whether it was a sophisticated smart-power reaction or a cruder hard-power reaction depended on the characteristics of the specific administration and the sectors of the elites that they represented.

By the late 20th century the logic of the structural adjustment policies of the neoliberal market reforms, which were promoted by the international financial institutions under the Washington Consensus, prevailed in the Western Hemisphere, supported by the institutional framework of the Inter-American system. 4 The US-centred power structure seemed stable, except for the existence of Cuba outside of its control.

During the transit to the 21st century, however, the electoral victory of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela and the development of the Bolivarian process triggered a shift to the political left in key South American States. Victories of leftist candidates and constitutional reforms in Ecuador and Bolivia were accompanied by less radical but relevant new left-leaning governments in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. The Sandinistas returned to government in Nicaragua, and other forces on the left of the political spectrum, albeit mostly moderate, gained influence and won elections in Central America and the Caribbean (Prieto Rozos 2014). Thus, the first years of the century brought a widespread transformation of the political landscape of the hemisphere.

At the core the leftward shift was the Bolivarian Alternative for the Peoples of Our America – Peoples’ Trade Agreement (ALBA-TCP). It became the only regional integration project in Latin America and the Caribbean seeking a comprehensive integration – defined as deep integration – beyond the strictly economic sphere. It opposed the neoliberal logic and aimed at implementing an alternative epistemology that sought to dismantle the colonial matrix sustained by post-colonial and neo-colonial subjects. It focused on local and global solidarities, and it promoted relations based on complementarities in order to compensate for asymmetries among member states, including cooperation in healthcare and education. ALBA-TCP proposed a path to development that embodied principles of South–South cooperation, thereby opposing the prevailing belief that only Western knowledge systems can lead to economic and social development. The alliance between Cuba and Venezuela was the origin and the bedrock of this counterhegemonic project (Feinberg 2020; ALBA-TCP n.d.).

As a key actor in the political shift, Cuba’s relations with other states in the region steadily improved. By 2009, the re-establishment of relations with El Salvador culminated a long process of reintegration and diplomatic recognition in the region. 5 Subsequently the non-recognition of Cuba by the US became a serious obstacle to good US–Latin American relations (Oliva Campos & Prevost 2017).

This process was a challenge for United States’ regional – and global – hegemony. One of its most visible results was the definitive collapse in 2005 of the US and Canadian plan for an all-encompassing hemispheric free trade area. This project could only be imperfectly replaced by a hub-and-spoke scheme in the form of several bilateral free trade agreements between Latin American and Caribbean countries, and groups of countries, with the United States and Canada.

A military coup in Honduras and a parliamentary coup in Paraguay in 2009, two countries in the early stages of very moderate leftward shifts, marked the first instances of the ebb of the leftist tide. Then the second decade of the century saw a visible turn to the right in South America, especially in Brazil – as a result of judicial-parliamentary coup – Argentina and Ecuador. The latter abandoned ALBA-TCP in 2018, thus weakening the alternative regional mechanisms of integration. This was followed by the hollowing out of institutions such as the Union of South-American Nations (UNASUR), and the emergence of mechanisms, like the Lima Group (2017) and the Forum for South-American Progress and Integration (PROSUR), launched by right-wing governments. Regional integration did not disappear, but it was partially realigned to the positions of conservative governments and the United States’ foreign policy objectives. A coup in Bolivia in 2019 that overthrew Evo Morales’ government marked the high point of the rightist flow tide in the region.

Nonetheless, the situation did not evolve steadily to favour US interests. The moderate Mexican left led by Angel Manuel Lopez Obrador conquered both the presidency and the Congress in 2018. Elections held in Bolivia in 2020 led MAS, Morales’ party, to take back the government. Mauricio Macri, the conservative president of Argentina, lost to a left-leaning ticket formed by Alberto Fernandez and Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner in 2020. In 2021, a Peruvian leftist formation won an extremely contested presidential election. Massive popular demonstrations against right-wing governments shocked Colombia and Chile for months, with the latter entering a process of important, albeit apparently moderate, political transformation. In the background of these events, Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua survived crises and mounting external pressure.

Hence, the stability of US dominance in the Western hemisphere faltered, creating a scenario of shifting balances and growing conflicts. Underlying the political change was the diminished importance of the United States economy as a determinant of wellbeing in the region. The structural transformation of the northern power and its global overreach opened room for China to play a growing role as a source of investment for Latin American and Caribbean countries and to become an increasingly decisive trade partner (Vadell 2019).

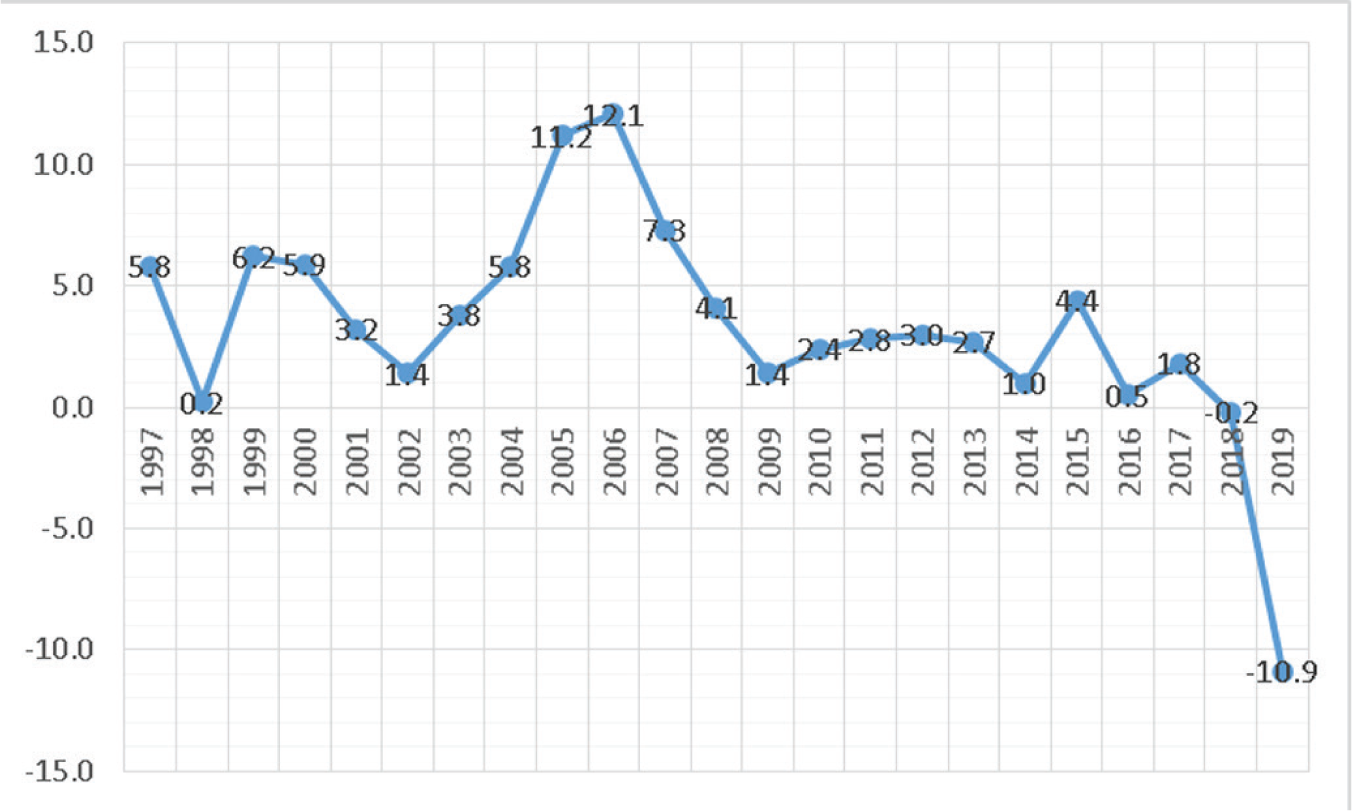

Cuba’s internal situation, as perceived by the US government, is the third main contextual variable. It comprises two key factors: the state of the economy and the political situation. In the 1990s, the Cuban economy plunged into an unprecedented crisis (Sanchez Egoscue & Triana Cordoví 2010). US policy-makers perceived Cuba’s economic weakness as a prospect for social instability and the fracturing of the internal political consensus, and thus as an opportunity to achieve their strategic goals. In the early years of this century the economy recovered, aided by the diversification of economic partnerships, the participation in integration projects and the transformation of Cuba’s economic structure. More recently, however, the situation worsened, as shown in Figure 2, in the context of a global structural crisis and the impact of both long-lasting and newly introduced economic sanctions. 6

Annual GDP Growth Rate, constant 1997 prices (%). Source: Created by the authors with data from ONEI (1998–2021).

Another factor that received special attention was the ageing of the Cuban political leadership, as the retirement of the most prominent figures was seen as a potential opening for advancing US interests. Yet, towards the end of the first decade of the 21st century, political stability subsisted, despite Fidel Castro’s retirement. The transition to a new generation began in 2008 and was completed in 2018.

In 2020 the country was hit by the pandemic of COVID-19, which not only created a public health crisis, but also affected some of the main sectors of the economy, especially tourism, thus severely straining the country’s available resources. It meant additional restrictions for the population in the form of scarcity of consumption goods, limited mobility due to public health policies and the threat of severe illness. This appears to have been interpreted by the US government as the conditions for a significant erosion of the popular support for the Cuban government.

In that context, large protests broke out on 11 July 2021, the most important since 1994, accompanied by riots, attacks on police officers and looting. Massive pro-government demonstrations took place in the following days and months (Carmona Tamayo & Álvarez Guerrero 2022). The situation in Cuba was clearly fluid and complex, which fuelled the idea among the opponents of its political system that it was at a low point, and hence vulnerable.

The third set of variables we examined is the domestic variables. The combination of these factors within United States is key for policy-making in any field, and Cuba policy is no exception.

There are three fundamental components of this group. The first one is the balance of forces among power groups, and their interest in Cuba or lack thereof. The influence that the Cuban American lobby and its supporters have is a particularly important part of this component. Here it is necessary to understand the value of the state of Florida and its specific dynamics. In an election for the President in the United States, 80 to 85% of the 538 electoral votes go to the Party that they went to in the recent past, and so they are considered “safe”. Florida’s 29 votes were 5.4% of the total 538 electoral votes for President, as of 2020. However, for over two decades, the Sunshine State has been the largest of the “swing states”, 7 with the lowest average margins between the candidates in the country. This means that it has five to six times that weight in the 15 to 20% of the truly “contested” electoral votes for President. From that comes Florida’s disproportional political importance. Therefore, a relatively small block of voters, combined with the ability of a determined group to mobilise them and to manage the process itself, can be decisive (Dominguez Lopez 2019).

One key factor in the transition of Florida from a Democrat stronghold to a swing state was the presence, growth and political activism of the Cuban American community, which built a political alliance with the Republican Party (Colburn 2013). The Cuban American vote was decisive in the contested election of George W. Bush in 2000, but it lost influence in 2008 (Rieff 2008). In 2012 it split nearly in half, as Barack Obama carried the state – twice – without the support of the Cuban American elites. In 2016 it swung back to the Republican side, with a large pro-Trump movement (Krogstad & Flores 2016), even though its effective impact on the outcome was considerably overstated in the aftermath of the 2016 election (Sopo & Grenier 2016).

More relevant is the development of the Cuban American political structure, controlled by the community’s elites and deeply connected with national political elites, particularly in the Republican Party. They have produced a number of organisations dedicated to lobby Congress and the President, but also to support electoral campaigns in Florida and other states, channel funds for their favourite candidates across the country and in general to use the political system to advance their interests. Two of them are particularly significant. First, the veteran Cuban American National Foundation, created in the 1980s largely with the support of Ronald Reagan’s administration and the neoconservative-new right movement (Haney & Vanderbush 1999). More recently, Cuban American elites and their allies created the Inspire America Foundation, which gathered a number of politicians, including former and sitting members of Congress and Senators (Inspire America Foundation 2019). Both organisations were staunch opponents of the Cuban government and of any attempt to normalise relations between the two countries without prior regime change in Havana. Both had the promotion of these kind of policies as their main priority, and were supported by companies and businessmen with vested interests on the matter.

These sectors had managed to gain an increased presence in the Federal Congress that had made them an overrepresented minority. Bob Menendez became Senator from New Jersey in 2006, Marco Rubio Senator from Florida in 2010 and Ted Cruz Senator from Texas in 2012 (United States Senate n.d.); Rubio and Cruz were candidates for the Republican nomination in 2016. The number of Cuban American federal representatives grew over the first decades of the century, and added more states. In 2001 there were two from Florida. As of 2021, there were seven from Florida, New Jersey, West Virginia, Ohio and New York (United States House of Representatives n.d.).

A different position was assumed by a number of actors, mostly agri-business, airlines, cruise companies and some telecommunications and high-tech companies, who were interested in the Cuban market or in the demand for travel services to the island. Their views were expressed by important organisations like the Chamber of Commerce (Frank 2017; US Chamber of Commerce 2019). Some of the same sectors supported the specialised lobby group Engage Cuba (2019), which focused on promoting legislation that could favour sales to, and investments in, Cuba. Their position regarding the general nature of Washington’s policies and goals was much less clear. More significantly, despite the resources that these sectors could muster, Cuba was not a top priority for most of them.

The balance of the influences by non-governmental actors depended on the relative strength of the groups involved, weighted by the level of priority assigned to the Cuba policy. For the anti-Cuban-government sectors and organisations, it was their top, or near top, policy goal. For most of the groups favourable to a policy change, it was a different matter. Their main goals were clearly the advancement of their specific economic interests, and in most cases inserting themselves into this small market was not a major goal, when compared to other interests associated to, for instance, regulation or taxation. Thus, the net balance shifted to a more intermediate position regarding specific policies over the first two decades of the 21st century, but not so much as to create a new equilibrium.

It would be reductive to portray the resulting policies simply as an outcome of the activity of these groups. There is evidence that their success is dependent on the orientation of the Executive in the matter (LeoGrande 2019). Hence, the second component in this group is the ideological orientation of the administrations. Here we have a very clear sequence regarding the presidents’ ideologies and views on foreign policy. In 2001–9, the George W. Bush administration was dominated by neoconservative perspectives, expressed in the so-called Bush Doctrine (President of the United States 2002, 2006), with its hard-power stance, the principle of preventive action and its unipolar view. In 2009–17, Barack Obama brought a change, leaning to a smart-power approach, open to change course when the previous orientation was failing and to better adjust its tools to concrete circumstances (President of the United States 2010, 2015). Donald Trump reverted to a blunt version of hard-power, less sophisticated than previous approaches (President of the United States 2017a). Joseph Biden administration’s actions in its first year basically amounted to a full continuity of Trump’s policies, despite rhetorical changes (President of the United States 2021).

The third component is the complex dynamic within Congress. The federal legislature had become increasingly polarised and nearly evenly divided between the two parties. Recent research has shown that this generated a relative stalemate that reduced the possibility of passing legislation, but reinforced the influence of individuals and small groups to force their interests through bargains and other forms of Congressional politics. These conditions impacted the “Cuba issue”, which was targeted by a significant number of bills, but failed to produce major legislation (Kopetski 2016; González Delgado et al. 2021; González Delgado & Domínguez López 2018).

What we see in the domestic variables is a dynamic system of power groups with different preferences and resources, as well as different degrees of interest in the issue. They interacted with an executive that oscillated between a hard-power neoconservative view, and a more nuanced smart-power view that favoured different approaches, with a Congress unable to pass significant legislation on the issue.

The Axes of the US Cuba Policy

This complex system of variables drove the making of the US Cuba policy through the mechanisms presented above. The study of the history and the fundamental doctrines and documents of US foreign policy leads immediately to a key corollary: when we combine the geopolitical value of Cuba with the US national project of global power, it follows that the control of Cuba was of fundamental strategic importance for Washington in the early 21st century, just as it was in the early 20th century. This was the basis for the fundamental strategic goal of Washington’s Cuba policy of regaining control of the island via regime change.

The necessity of regime change has been a sine qua non condition of the US Cuba policy throughout this century, given the deeply interwoven nature of sovereignty and the socio-political system in Cuba. In this respect, it is particularly telling that Barack Obama, in his speech on 17 December 2014 announcing a change of policy, said in clear terms that he was changing the means of US policy, not its goals (Obama 2014). Regardless of the public targeted by that particular statement in that multilayered speech, the implication is that the change occurred at the public policy level, but the state policy remained the same. Hence in the 21st century it remained the same as in 1959, and it was consistent with the US’ historic projection toward Cuba and the region.

The specific policies were articulated around three main axes. The first set are the economic sanctions. These became a centrepiece of US policy toward Cuba soon after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution (Zaldivar 2003, Lamrani 2013). Their role was determined early on, as was stated in a 1960 secret memorandum from the US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs to the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. He explicitly wrote in that document that the only foreseeable means to reduce and potentially eliminate the Cuban people’s support for the government that had emerged from the Revolution was through “disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship” (Mallory 1960). The implication is that the sanctions be targeted at the Cuban people, as a means to achieve the overthrow of the government.

The system of sanctions was implemented through a massive entanglement of laws, executive orders, presidential proclamations and other regulations. Their early forms were integrated by Presidential Proclamation 3447 of 3 February 1962, that established what is called an embargo in the United States and a blockade in Cuba. The initial core of this embargo/blockade stemmed from the application to Cuba of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, which allowed the introduction of the Cuban Assets Control Regulation of 1963 and other regulations. This included trade control, suspension of aid and technical assistance, freezing financial assets, and blacklisting foreign companies that do business with Cuba (Doxey 1980). This generated a chilling effect on potential investors, who are critical for a small economy that needs foreign direct investment to access technology and markets. These US sanctions were not merely a bilateral trade embargo, but rather they had considerable extraterritorial reach (Morley 1984), and consequently they have brought about much broader damage to Cuba’s economy and society than would result from a bilateral trade embargo.

As a preamble to the 21st century, new legislation tightened the whole system considerably. The most significant of these measures were the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992, also known as the Torricelli Act (US Congress 1992), and the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act (LIBERTAD), also known as the Helms-Burton Act (US Congress 1996). These laws imposed severe penalties on ships that enter a US port within six months of stopping at a Cuban port, and crippling restrictions on foreign subsidiaries of US companies trying to trade with Cuba. They prohibit any transactions with Cuba using US dollars, and they permit US nationals to bring suit in US courts against foreign companies doing business on properties that were held by US nationals prior to the Revolution. 8 They stand out due to their extraterritoriality and long-term impact.

The 21st century brought a significant increase in the use of economic sanctions as a weapon of choice by US foreign policy. According to a document by the Department of the Treasury, starting with the beginning of the 21st century, “economic and financial sanctions became a tool of first resort to address a range of threats to the national security, foreign policy, and the economy of the United States”, noting that between 2000 and 2021 the use of sanctions increased 993% (Department of the Treasury 2021). A large part of them are designated as targeted or smart sanctions, that supposedly affect individuals or organisations rather entire populations. However, there is evidence that their impact is effectively comprehensive (Gordon 2019).

In 2000, the US Congress passed the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act (TSRA). It required the President to end any unilateral agricultural and medical sanctions implemented by the Department of the Treasury or the Department of Commerce. Consequently, it opened for the first time the possibility of exporting to Cuba, albeit with harsh preconditions (US Congress 2000). However, it explicitly excluded Cuba from the general mechanisms to potentially lift existing sanctions, due to the provisions of the Torricelli and Helms-Burton Acts.

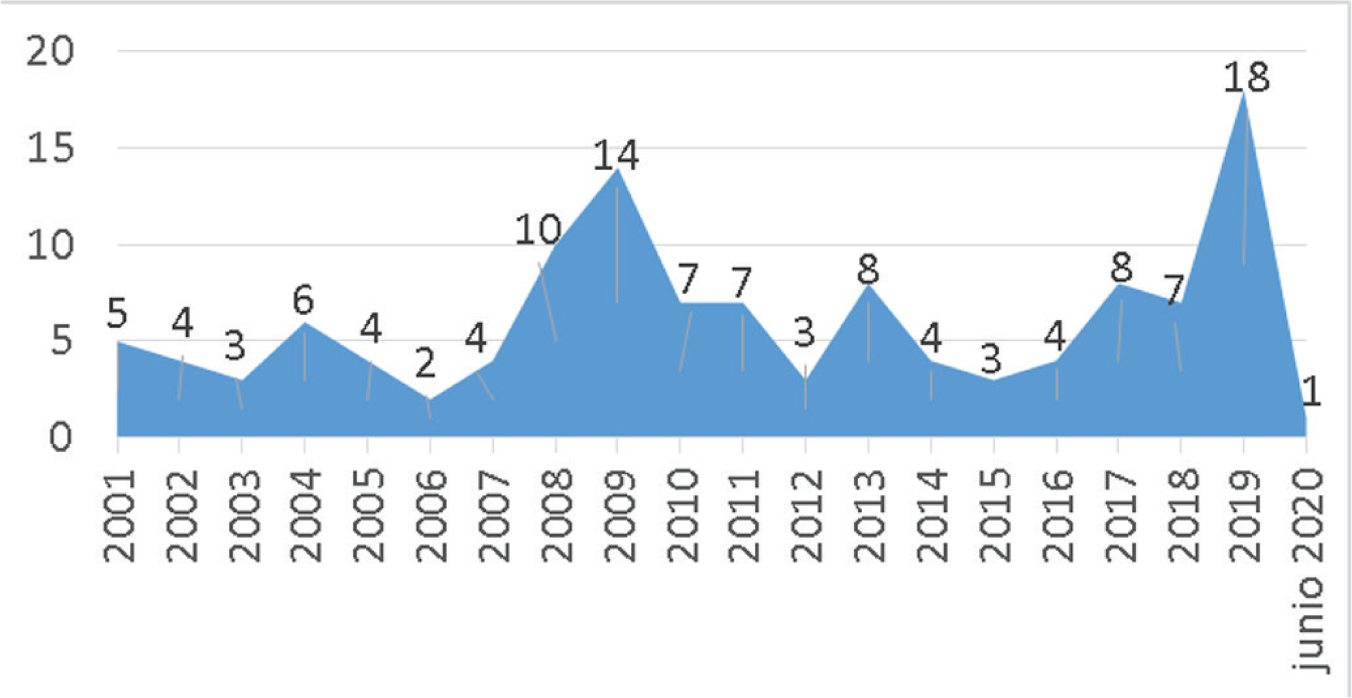

Barrera Rodriguez and Iturriaga Bartuste (2020) found that the system of sanctions was very dynamic during the first two decades of the 21st century. Between January 2001 and June 2020, that is, during the administrations of George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump, new regulations were introduced every year, for a total of 122, as shown in Figure 3. It is worth noticing that these were not applications of existing sanctions, but the renovation of some that were about to expire and the introduction of new ones. The latter consisted, mainly, in the inclusion of the Cuban government in various US international sanctions lists 9 and backlisting Cuban entities and individuals. The frequency of the changes in the regulations that these constituted itself had a major additional impact: it was increasingly difficult for interested businesses to determine the feasibility of operating in Cuba without risking punishment.

New sanctions, 20 January 2001–June 2020. Source: Barrera Rodríguez & Iturriaga Bartuste (2020: 34)

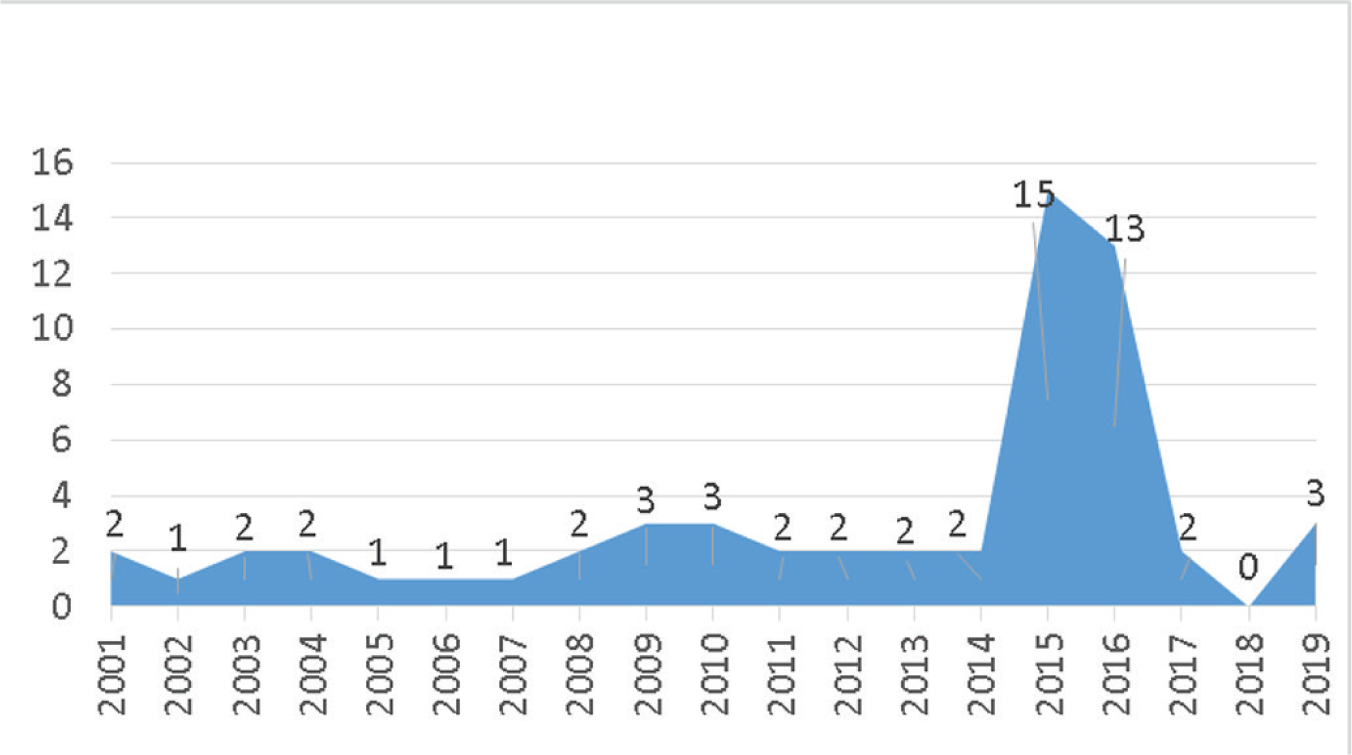

The period 2015–2017 is seen as a hiatus in which the embargo/blockade was softened, following Obama’s new approach. Barrera Rodriguez and Iturriaga Bartuste (2020) identified 59 instances of policy changes that increased the flexibility of the sanctions in 2001–20, the bulk of which were passed in 2015 and 2016 (28), as shown in Figure 4. Thus, it seems that this view is valid. However, it is important to keep in mind that the core elements of the blockade remained in place, even when modifications were implemented using the executive power of the presidency.

Actions to make the blockade more flexible, 20 January 2001–June 2020. Source: Barrera Rodríguez & Iturriaga Bartuste (2020: 36)

The increased flexibility resulted mostly from deleting names of individuals and entities from the blacklists, the introduction of general licences for legal categories of travellers that could visit Cuba, and the authorisation of some business activities, such as the operation of some hotels in Cuba by US companies, or the incorporation of Cuban private renters into AirBnB. The prohibition of regular banking operations and touristic travel, however, continued without significant change, and the general regulations, including those from the 1960s, remained untouched (Barrera Rodriguez & Iturriaga Bartuste 2020).

The observed change in the justification of the sanctions against Cuba is also significant. During the first three decades of their existence, they were justified on the basis of the threat of Communism in the Western Hemisphere (Mallory 1960). From the 1990s, the focus shifted to two different issues: Cuba’s alleged support for terrorism and its human rights performance. The former was expressed in the inclusion of the island on the list of countries that promote terrorism. However, the supporting arguments included in the documents grew thin over the years (Bureau of Counterterrorism 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017; Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism; 2011, 2005; Sullivan and Beittel 2015; Sullivan 2005). The second idea appeared constantly in US political speech and in the preamble of new sanctions. However, even according to Human Rights Watch, violations of human rights in Cuba were always fairly minor when compared to those recorded in countries like Saudi Arabia and Colombia (Humans Rights Watch 2021), countries considered allies by Washington.

The second main axis of US Cuba policy is US support – and often creation – of political opposition to the Cuban government, both within and outside Cuba.

Since the early times of the revolution, Washington supported or created groups to oppose the new government, based either in Cuba or abroad – many of them were located in United States. For years, many of those organisations engaged in actions that currently would be classified as state-sponsored terrorism (Bolender 2010). The justification for these and other actions – including Bay of Pigs – was the threat of Communism in the hemisphere.

After the end of the Cold War and the concomitant collapse of the value of anti-Communism to justify US policies toward Cuba, the claim to be promoting democracy in the island took its place. It was not a new idea, as the Cold War itself was largely presented as the opposition between democracy (or freedom) and Communism (or oppression). But the declared goal of promoting democracy in Cuba, associated to the island’s government’s alleged poor performance in human rights, allowed the transition from black operations to openly dedicating $20-30 million of the US annual federal budget to democracy promotion in the Caribbean country. Large parts of that funding went to media outlets dedicated to two main goals: creating an image of Cuba as an enemy (Bolender 2019) and as a repressive regime and thus justifying US actions, and directly influencing the Cuban population, thus alienating both domestic and international support. Further amounts of money were appropriated to fund the operation of US government agencies targeting Cuba (Sullivan 2010, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017).

In the 2000s the oldest media organisations specialised in Cuba and dedicated to these tasks were Radio and TV Marti, under the Office of Cuba Broadcasting, legally a part of US government. The latter was under the supervision of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), a federal organisation created in 1999. In 2018 the BBG changed its name to United States Agency for Global Media (USAGM), to reflect the incorporation and integration of a wide variety of new platforms.

The George W. Bush administration launched a new plan for Cuba intended to coordinate a wide variety of organisations and projects in order improve the US efforts to produce a transition in Cuba – that is, regime range This was supervised by the Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba, a federal structure formed by senior government officials and members of the cabinet. The Commission was chaired initially by then Secretary of State Colin Powell, and later co-chaired by then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and then Secretary of Commerce Carlos Gutierrez (Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba 2004, 2006). In 2004, TV Marti’s operation was expanded to 24 hours a day, and Radio Marti’s to 24 hours for six days, and 18 hours for one day per week (Broadcasting Board of Governors 2004). Old opposition groups that were shaped in the form of traditional political parties, like Christian Liberation Movement (MLC), founded by Oswaldo Paya (Movimiento Cristiano de Liberación 1999), were revamped. The US promoted the creation of new groups that took the form of social movements, such as the Ladies in White, initially formed in 2003 by the wives of several dissidents who had been incarcerated (Las Damas de Blanco). Information released by WikiLeaks shows that the US Interest Section in Havana asked for funds for the Ladies in White, and systematically worked with its leaders (Bayard de Volo 2016).

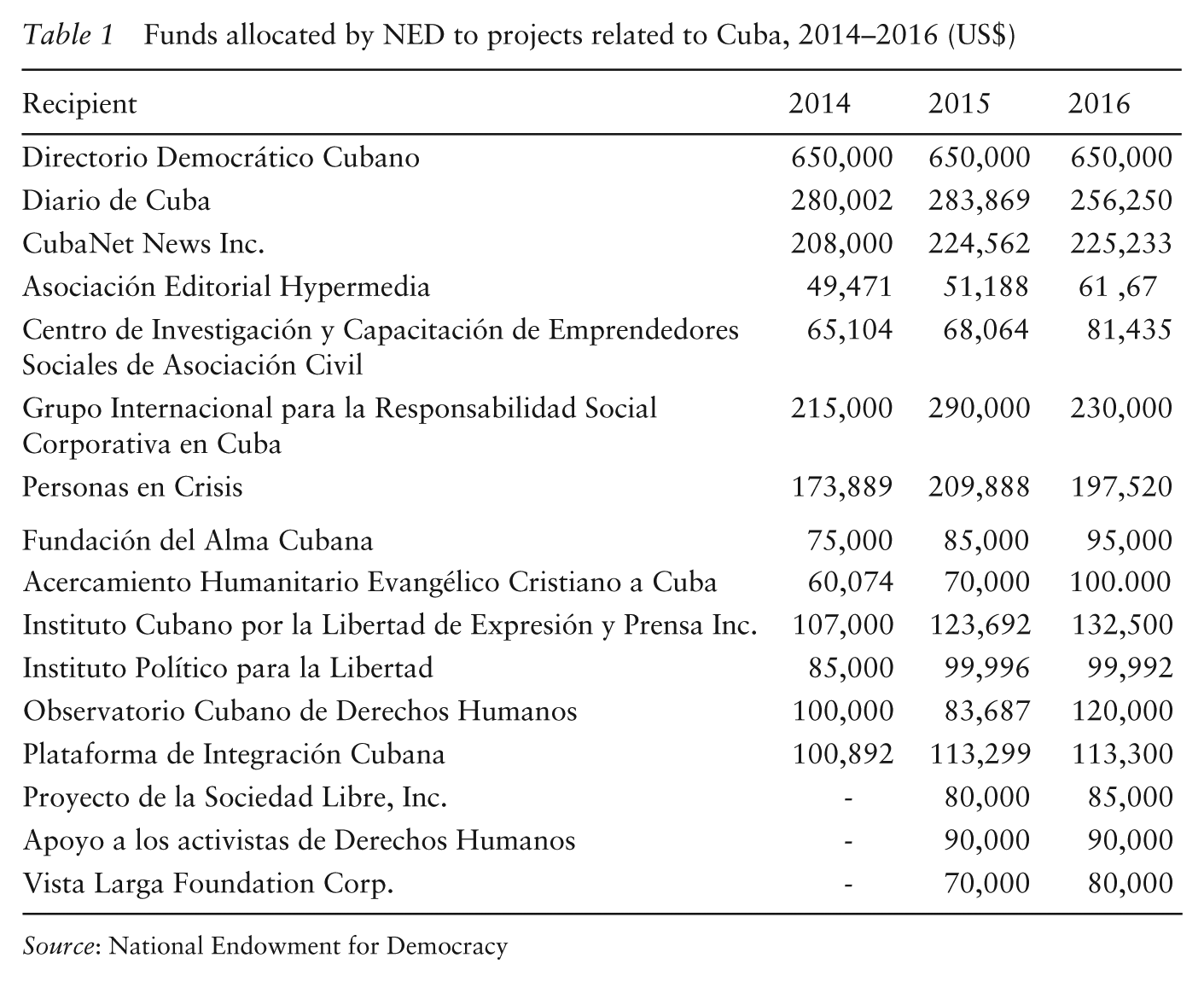

The Obama administration strengthened and diversified the distribution platforms of the OCB using Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and text messaging, and person-to-person distribution via flash drives, DVDs and Bluetooth connections. 10 It also strengthened the funnelling of funds for projects and organisations in Cuba and abroad through NGOs. The most important cases were the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Table 1 show the distribution of NED’s funds in 2014–16.

Funds allocated by NED to projects related to Cuba, 2014–2016 (US$)

Source: National Endowment for Democracy

These projects declared a spectrum of goals: technical assistance to civic activists in Cuba; training, funding and provision of platforms for independent journalists, artists and academics that report violations of freedom, democracy and human rights in Cuba; training of young leaders; promotion of democracy and freedom of speech; spreading their view on the situation of the Cuban youth throughout Latin America; publishing the work of independent writers; training independent trade union leaders and providing them with financial resources and means of communication; promoting freedom of religion; distributing propaganda around the country to promote democracy; training “agents of democracy” in the use of internet, social media and other technological tools; supporting Cuba’s civil society in their contacts with US, Europe and Latin America; and spreading reports of racial problems in Cuba.

The Trump administration continued to funnel money in the same way. Table 2 shows the amounts allocated by the NED to Cuba related projects in 2020, and their declared goals.

These lists are not exhaustive. Nevertheless, they indicate the goals of these policies. More recently, in September 2021 under the Biden administration, USAID awarded $6,669,000 in grants for projects aimed at Cuba. The distribution is shown in Table 3.

Older programmes did not disappear. Rather, they became part of a broader and fast-growing network: at the time of writing this article, the OCB continued to broadcast (United States Agency for Global Media 2021) and the Ladies in White and other groups remained active. As a whole, these and similar projects were intended to together form a system of organisations that could influence perceptions of Cubans, and especially the youth, of their situation and of their government’s performance in a series of dimensions, and to train and fund an array of agents categorised as intellectuals, unionists and civic leaders. They were also intended to build a biased image of Cuba in Latin America and the rest of the world. As the lists show, their primary targets in Cuba were journalists, artists and private entrepreneurs, which means sectors that could directly influence public opinion both inside and outside Cuba. It was also hoped, and promoted, that this latter group would form the leadership of an emerging sector of the economy with the potential to generate a social class that could contend for power, and with that conduct a transition to a capitalist economy.

The third axis is negotiations. Here there is indeed a history of dialogue. Since 1959 there were initiatives by one government or the other seeking to negotiate some form of settlement of some of the contested issues, most of them secret (LeoGrande & Kornbluh 2015) The first major attempt, with rather minor results, happened in the late 1970s, during the James Carter administration. In 1977, Carter became the first US president to direct his officials to “attempt to achieve normalization of our relations with Cuba.” He authorised a series of steps and secret communications with the Cubans (President of the United States 1977). The main achievement of this effort was the establishment in 1978 of interest offices of each country in the other, each hosted by a third country’s embassy, the first form of permanent diplomatic representations since 1960. The negotiations of the 1970s also led to the restoration of family visits for Cubans living in the US, travel by US citizens to Cuba and a treaty of maritime boundaries (Ramirez Cañedo & Morales Dominguez 2014).

The Ronald Reagan administration (1981–9) changed course back to a more traditional confrontational policy. However, during that period both governments reached their first accord to regulate Cuban migration to United States, which included issuing up to 20,000 immigrant visas per year, a response to the migratory crisis of 1980 that is known as the Mariel boatlift. In 1994, in the midst of the economic crisis of the 1990s in Cuba, a new migratory crisis, the “balseros” crisis, led to new negotiations. In September 1994 both governments agreed that the US would issue at least 20,000 immigrant visas for Cubans annually, in exchange for Cuba’s pledge to prevent further unlawful departures by rafters. The implementation of the agreement was overseen by Cuban and US officials who met twice a year, once each in Washington and Havana. Shortly after, the William Clinton administration established the wet foot-dry foot policy, an interpretation of the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 that essentially granted the status of political refugee to any Cuban that reached US soil, regardless of by what means (Aja 2014). Thus, by the year 2000, negotiations and contacts had occurred, but with relatively limited results despite some important agreements, and with just one instance of Washington assuming a significant pro-dialogue approach.

The first two decades of the 21st century encompassed three administrations and the first part of a fourth that took different stances on US relations with Cuba. The George W. Bush administration (2001–9) adopted a confrontational approach and had limited contacts, those through “formal and technical” meetings mostly dealing with the monitoring and oversight of the 1994 migration accords. Some forms of technical cooperation did occur, with the participation of US federal agencies and Cuba institutions. An illustrative case is the cooperation between NOAA’s National Hurricane Center and Cuba’s National Institute of Meteorology (Reed 2018).

The dialogue and negotiations for the most significant attempt to change the state of US relations to Cuba occurred during Barack Obama’s second term (2013–17). Secret conversations in 2013–1411 led to the reopening of both countries’ embassies, and the creation of an agenda for the bilateral dialogue. This was intended as the beginning of a process of normalising relations between Cuba and the United States (LeoGrande & Kornbluh 2015). 12 This approach also meant the recognition of the Cuban government by Washington as a legitimate representative of the Cuban people.

In the following two-year period (2015–17), unprecedented and intense bilateral negotiations led to the signing of an important number of bilateral agreements in numerous fields: marine protected areas (November 2015); environmental cooperation on a range of issues (November 2015); direct mail service (December 2015); civil aviation (February 2016); maritime issues related to hydrography and maritime navigation (February 2016); agriculture (March 2016); health cooperation (June 2016); counternarcotic cooperation (July 2016); federal air marshals (September 2016); cancer research (October 2016); seismology (December 2016); meteorology (December 2016); wildlife conservation (December 2016); animal and plant health (January 2017); oil spill preparedness and response (January 2017); law enforcement cooperation (January 2017); and search and rescue (January 2017). The United States and Cuba also signed a bilateral treaty in January 2017 delimiting their maritime boundary in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Bilateral dialogues were held on all of these issues as well as on other issues, including counterterrorism, claims (US property, unsatisfied court judgments and US government claims), economic and regulatory issues, human rights, renewable energy and efficiency, trafficking in persons and migration (Congressional Research Service 2021).

The opening of a regular diplomatic representation provided the US government with a permanent presence that it had lacked, and as such a new source of information and a potential means to exercise some degree of influence on Cuba, including increased contacts with internal dissidents. All the topics involved in the dialogue were of the interest to one segment or another of the US elites and its political class. In the eyes of Washington, the new contacts had the potential to create the conditions for a gradual acceptance of US leadership in an asymmetric relation. This conclusion follows from the fact that the state policy remained unchanged, and from official documents published by the White House in the process, as guidelines for the process (President of the United States 2016).

President Donald Trump unveiled a reversal of the policy toward Cuba in 2017 (President of the United States 2017b), introducing new sanctions and rolling back some of the Obama administration’s efforts to normalise relations. By 2019, the Trump administration had largely abandoned the engagement. The still unexplained health incidents that affected US diplomatic personnel in Havana were used as a pretext to downgrade the embassies in both capitals, and to basically eliminate diplomatic contacts as well as to significantly reduce all monitoring and implementation of most agreements, including even the 1994 immigration accords (Edson 2017). The Joe Biden administration, during its first year, restored none of the lines of contact opened by Obama.

Hence, we observe a high degree of activity along the three main axes of the US Cuba policy during the early 21st century. Concrete actions were articulated in ways that were largely in line with historical trends, albeit with significant adjustments in the form of modernisation of some of the instruments, as well as with important variations at some specific moments, particularly during the Obama administration.

Conclusions

The history of US policy toward Cuba after 1959 has become one of the most internationally renowned case studies of US intervention and efforts for regime change in Latin America during the Cold War and its aftermath. The regional context in the early 21st century was marked by the shifting contours of Latin America’s engagement in the global economy, the underlying political trends in the region and the changing configuration of regional institutions and alliances. Accordingly, the dynamics of Washington’s policy toward Cuba must be understood in the context of a shifting international system and complex regional processes.

In those conditions, the US’ state policy on the subject remained unchanged as the guideline for specific policies. The latter, however, did evolve, driven by variations in other major variables. We identified three distinct moments, associated with the configuration of the balance of domestic actors, which showed a form of unstable equilibrium conducive to a relative stalemate of the legislative process and the dominant orientation of each administration. The resulting configurations interacted with the situation in Cuba and the way it was perceived, which went from the idea that the island would experience a crisis associated to the generational change of leadership, to the perception that it was essentially stable thus requiring a different approach, to a perception of weakness in the midst of a deep crisis. This was also encapsulated by the emerging imperatives created by the relative weakening of United States as hegemonic power and the regional reality.

The result was a first period – the Bush administration – that introduced additional and harsher sanctions and restricted direct contacts to a minimum; a second period – the Obama administration – that made the blockade to some extent more flexible and engaged in negotiations on an array of relevant topics; and a third period – the Trump administration and the first year of Biden administration – that increased the sanctions and made them more comprehensive, while ending essentially all negotiations. The general trend was an increased use of economic sanctions, consistent with the observed behaviour of US foreign policy as a whole. It is significant that the second axis, the provision of support for opposition groups within and outside Cuba, did not show the same oscillation; rather, there was a linear progression in this area.

From here follows that the observed variations were consistent with the common strategic goals, and that while they indicate different approaches to foreign policy and distinct correlations of forces among actors and their specific interests, they did so within a form of flexible consensus at the highest level of US political organisation. The general trend suggests that forms of policy associated with the soft-power approach became less effective, or were perceived as less effective, in the longer term, in spite of Obama’s more nuanced view. It is possible that future configurations and conditions could again generate a change from the current hard-power policies. However, it is not clear if United States power elites will again feel in a position to try to manage this particular issue in a manner consistent with a process of adaptation to an international system in transformation, or if to the contrary, the continual relative decline of US power and the related gridlock of its political system will leave it unable to break out of its status quo. Future studies need to explore these avenues.