Introduction

History teaches us clearly that the battle against colonialism does not run straight away along the lines of nationalism. For a very long time the native devotes his energies to ending certain definite abuses: forced labour, corporal punishment, inequality of salaries, limitation of political rights, etc. This fight for democracy against the oppression of mankind will slowly leave the confusion of neo-liberal universalism to emerge, sometimes laboriously, as a claim to nationhood. It so happens that the unpreparedness of the educated classes, the lack of practical links between them and the mass of the people, their laziness, and, let it be said, their cowardice at the decisive moment of the struggle, will give rise to tragic mishaps.

– Frantz Fanon, ‘The Pitfalls of National Consciousness’, The Wretched of the Earth, 1961

Recent history teaches us that the battle against super-exploitative extractivism does not run straight away along the lines of resource nationalism. For a very long time the critic devotes their energies to ending certain definite abuses: lack of revenue transparency, inadequate community consultation and participation, abuse of worker safety and health, and illicit financial flows (not to be confused with ‘licit’ outflows, no matter how dubious are profit and dividend repatriations). This fight for clean mining and fossil fuel extraction, against the oppression of multinational corporations and captured states, will slowly leave the confusion of neoliberal universalism to emerge, sometimes laboriously, as a claim to nationhood. It so happens, now as for Fanon, ‘that the unpreparedness of the educated classes, the lack of practical links between them and the mass of the people (and the environment), their laziness and, let it be said, their cowardice at the decisive moment of the struggle, will give rise to tragic mishaps’.

The ideology known as resource nationalism is one such tragic mishap. Another is the universal neoliberal measure, gross domestic product (GDP) and associated national income accounting used to assess progress and prosperity. Laziness means that those supporting resource nationalism have, as Samir Amin (2018, 86) put it, ‘passed an eraser over the analyses advanced by Marx on this subject and taken the point of view of the bourgeoisie – equated to an atemporal “rational” point of view – in regard to the exploitation of natural resources’.

Thanks to this eraser, the term ‘pitfall’ can be understood by the invisibility or unexpected character of a danger, disruption or blind spot that lies directly ahead. Amin’s condemnation of an atemporal ‘rational’ point of view suggests resource nationalists who simply consider immediate extraction-related costs and benefits – without consideration of future generations’ legitimate interests such as slowing down the depletion rate and phasing out greenhouse gas emissions. They usually stress extraction benefits: technology transfers, new infrastructure for the project and related transport of mineral ores, smelted product or fuels, jobs (no matter how temporary), economic linkages backwards to suppliers or forwards to purchasers, royalties and taxes, and foreign exchange revenues. Vast costs are, in the process, erased.

Waves of resource nationalism defined and contested

To illustrate, for three of the most prominent resource-nationalism advocates – Alexander Caramento, Richard G. Saunders and Miles Larmer (2023, 340–341) – the regulatory agenda entails harnessing these benefits to aid extraction and capital accumulation:

First, the maximisation of public revenue from resource extraction, which includes measures such as increased royalties, taxes, and duties on extractive industries and the removal or limitation of tax exemptions and deductions. Secondly, the regulation and ownership of extractive industries, which includes measures such as the creation or renovation of state regulatory bodies and the outright or partial nationalisation of privately owned assets. Lastly, the enhancement of developmental spillovers from extractive industries, which typically includes the cultivation of backward and forward linkages, such as the implementation of local content measures in the case of the former, or the utilisation of domestic mineral processing and metal fabrication facilities in the case of the latter.

However, as Elisa Greco (2020, 511) remarks, ‘contemporary neo-extractivist policies in Africa nowadays are nowhere near as ambitious as those once attempted by African socialist governments.’ In the revived resource nationalism identified with the 2009 Africa Mining Vision process, Caramento, Saunders and Larmer (2023, 341) observe muted reforms:

Resource nationalism’s second wave, which emerged in the late 2000s, has been restrained in its preferred regulatory interventions compared with typical first-wave strategies. For the most part, private-sector control of the large-scale extractives sector was left intact. There were few attempts to nationalise or indigenise substantial mining assets and, instead, strategies typically aimed to increase mineral revenues through new taxation measures, improve regulatory oversight through capacity-building and cultivate productive linkages between mining and other economic sectors.

The problem with this perspective is not only the environmental and gender eraser, because nowhere in such a list would a resource-nationalist scholar, NGO advocate (e.g. in the Publish What You Pay network) or policymaker ever encounter the need to calculate – much less attempt to minimise – resource depletion, local pollution, greenhouse gas emissions or unreasonable forms of gendered social-reproduction subsidies to capital. Although hundreds of community-based movements make this case, they also typically suffer analytical erasure.

To be fair, Caramento, Saunders and Larmer (2023, 347) do recognise conflicts where activists claim that the costs of extractive industries outweigh the benefits:

In cases where communities protested such encroachment, national governments – who increasingly depended on resource extraction as a source of fiscal revenues – tended to side with the foreign investors. More fundamentally, critics argued, neo-extractivism led to the ‘reprimarisation’ of Latin America, returning regional economies to their dependence on primary commodity exports, rendering them increasingly vulnerable to market price fluctuations.

But these are partial caveats about resource nationalism, still inadequate due to their erasure of the extraction, processing, transport and consumption costs of non-renewable natural resource abuse. Such costs depend upon the extent of an extractivist project’s reach into economy, society and nature, and upon local conditions, including the relative laziness of the state (or of resource-nationalist experts). In a far deeper way than resource nationalists would recognise, vast damages are found in these 10 categories:

Ecological: degradation and pollution of local land, air, water, ecosystems and living bodies

Socio-psychological: displacement, gendered violence and aesthetic destruction

Labour and health: migrant work systems (family degradation), workplace safety and disease

Spiritual/traditional: despoliation of sacred sites (e.g. graves) and common spaces

Political (local, national): elite formation, corruption and compradorism

Geo-political: imperial, sub-imperial and local turf battles over extraction and transport

Mal-developmental: ‘Dutch Disease’ economic skew (against local manufacturing) and abuse of electricity (needed for labour-intensive industry, small businesses and households)

Financial: price volatility, illicit (and licit) financial flows, raises unnecessary foreign debt

Ecological-economic: ‘natural capital’ wealth depletion is adverse for future generations

Climatic: fossil fuel emissions, including in mining, processing, smelting and transport.

These represent what David Harvey (2003) terms systematic ‘accumulation by dispossession’. Environmental economists consider these ‘externalities’ as costs beyond market self-correction: damages carried by societies and ecologies. To take them seriously implies a full-cost accounting, one that may result in this pessimistic conclusion: resource nationalism has such vast pitfalls that serious sovereign consciousness would result in support to anti-extractivist movements aiming to leave minerals and fossil fuels underground, not half-hearted reforms (e.g. the Africa Mining Vision) with no prospect of changing power relations or of ending resource-driven underdevelopment.

The resource-nationalist eraser

To avoid asking such questions, resource-nationalist research funding – for example, for the team assembled by Caramento, Saunders and Larmer (2023) – is often available from agencies within the imperialist/sub-imperialist, pro-extractivist circuits. In Canada, the world’s most expansive extractive industry’s interests are continually being advanced, against African societies’ and ecologies’ interests, as discussed below. Still, even authors without such funding – for example, most contributors to the Review of African Political Economy’s special issues on political ecology (issues 42, 74 and 177–178) – also suffer from the Amin eraser: carelessly ignoring the implications of depletion, pollution, emissions and social reproduction.

As a rare exception at Roape.net, in 2018 Zsuzsánna Biedermann conceded ‘the finite nature of exhaustible natural resources: transitory extra income allows increased consumption but only for a certain period of time. What happens when the resource is depleted?’ (Biedermann 2018). She answered, using a Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis projection, that after diamond depletion, between 2025 and 2027 GDP will fall ‘47% below the non-depletion path’. But the broader point relates not to the ubiquitous and highly damaging concept of GDP (developed in 1934 by a white male US economist, Simon Kuznets), but instead to the central feature of Africa’s ‘dependency curse’ (to quote Biedermann): the decline in mineral wealth suffered by Botswana as a sovereign state, one of the three worst cases in Africa (World Bank 2021). Yet management of diamonds in Gaborone is considered a best-case site for resource nationalists, due to the state-owned Debswana company’s sharing of diamond mining spoils, even if wealth depletion has occurred in a manner favouring an acquisitive, unproductive elite in the bureaucratic managerial class. Added to landholding inequality, Botswana is one of the world’s worst cases of wealth disparity: ‘the top 10% of households in the income distribution own 57% of all assets and 61% of financial assets, while the bottom 50% own only 4.2% and 3.3%, respectively’ (United Nations 2023, 14).

In a more recent effort at assessing unequal ecological exchange, Dylan Sullivan and Jason Hickel (2025) write at Roape.net that ‘African countries are compelled to export more materials, energy, and other resources than they receive in imports’, and hence ‘Africa’s productive capacity and material output was redirected away from regional needs toward exports. However, even while physical exports were increasing, there was a decline in the total amount of money that Africa received for them.’ Yet while this is true for the 1980–2002 period of study, four problems arise. First, some materials – cash crops – are renewable, while others – minerals and fossil fuels – are not, a vital distinction when it comes to the permanent loss of Africa’s natural wealth (not just trade-derived income), which makes the unequal ecological exchange a much more serious factor. Second, the interest due on Africa’s sovereign debt is not considered by Sullivan and Hickel, yet its rapid rise from 1979 due to the Volcker Shock was the leading cause of both extreme financial exploitation and the continent’s subsequent forced export orientation for the sake of raising foreign exchange to repay foreign loans (even though much of the debt was ‘odious’ and repayment should have been questioned). Third, the trade-based measure of exploitation deployed could be reversed – as was the case during the commodity super-cycle of 2002–14 and then the 2020–22 uptick – when windfall profits accrue to those agents (mostly companies but also African states via royalties and to some extent workers) benefiting from resource extraction in Africa, due simply to price increases. Fourth, pollution and greenhouse gas emissions associated with extraction, smelting and processing mineral and fossil-fuel outputs from Africa also impose enormous costs that would make the case much stronger.

Wealth depletion is a critical factor in unequal ecological exchange. As the late Ian Taylor (2020, 9) reported in The Palgrave Handbook of African Political Economy – one of only two authors in this major work to contemplate the continent’s non-renewable resources – integral to ‘this depletion of finite resources and a subsequent negative debit on a country’s stock, inequality has been reinscribed’, given the comprador nature of resource managers. Taylor (2020, 7) continues:

calculations of GDP do not make deductions for the depreciation of fabricated assets or for the depletion and degradation of natural resources. Thus, a country can have very high growth rates calculated using GDP indicators, whilst embarking on a short-term and unsustainable exploitation of its finite resources.

In that collection’s other resource-conscious essay, Alexis Habiyaremye (2020, 713) observes how:

Depletion of natural capital by foreign exploitation also contributes to impoverishing the continent. The World Bank estimates with 1995–2015 data indicate that Sub-Saharan Africa has been losing roughly US$100 billion of Adjusted Net Savings per year, mainly due to natural resource depletion.

The US$100 billion annual loss is a profound underestimate in part because of methodological shortcomings, especially in relation to climate damage and the limited choice of minerals within the World Bank’s natural capital accounts (Bond 2025). Adding updated greenhouse gas emissions costings – prolific in the extractive industries due to energy consumed in deep mining, processing and smelting – and local pollution costs, as well as social reproduction subsidies by women, should be central concerns for any scholar aiming to balance resource potentials and pitfalls.

Accounting for resource depletion, (local) pollution and (global) emissions

Natural resource valuation is vital mainly because the standard unit of mainstream economics, GDP, measures income from sales of natural resources. But GDP contains no formal debit for depletion of non-renewable resources. In Marxian terms, such depletion – as well as ecosystem damage through local pollution and greenhouse gas emissions – was termed a ‘free gift of nature’ to capital. As Rosa Luxemburg argued in 1913, followed by Harvey (2003) and Amin (2018), this (plus women’s unpaid social reproduction labour) represents capitalism’s systemic appropriation of the non-capitalist realms (Bond 2021). Luxemburg (1913, 349–350) condemned capital’s environmental degradation in Africa, citing ‘land, game in primeval forests, minerals, precious stones and ores, products of exotic flora such as rubber, etc … The most important of these productive forces is of course the land, its hidden mineral treasure.’ For Amin (1974), the implications of super-exploitation emerged from both the differential rates of surplus-value extraction identified in Accumulation on a World Scale and capitalism’s abusive contact with non-capitalist ecological relations: ‘Capitalist accumulation is founded on the destruction of the bases of all wealth: human beings and their natural environment’ (Amin 2018).

Even bourgeois economists began to address resource depletion and ecosystem destruction once Nobel Laureate Robert Solow (1974) and his colleague John Hartwick (1977) established an asset measurement lens. They asked whether shrinkage of ‘natural capital’ due to exploitation of natural resources can be offset by the resulting investment in productive capital and ‘human capital’ (education expenditures). They insisted that if pollution or shrinkage of ecological wealth (e.g. minerals extraction) were to occur, it should be permitted only if benefits – that is, profits, taxes and wages that can be counted up and down the value chain – then flow into the expansion of productive or human capital. The point here is to protect the interests of future generations who have a notional ‘right’ to also draw down a society’s non-renewable natural resource base, the way ‘family silver’ is considered the basis for responsible stewardship and, in some cases, formal ‘trusteeship’ (Bond and Basu 2021). A net positive outcome (termed ‘weak sustainability’) assumes the substitutability of these various capitals: lost natural capital is offset by reinvestments of profits into machinery, infrastructure or schooling that makes capitalism more productive.

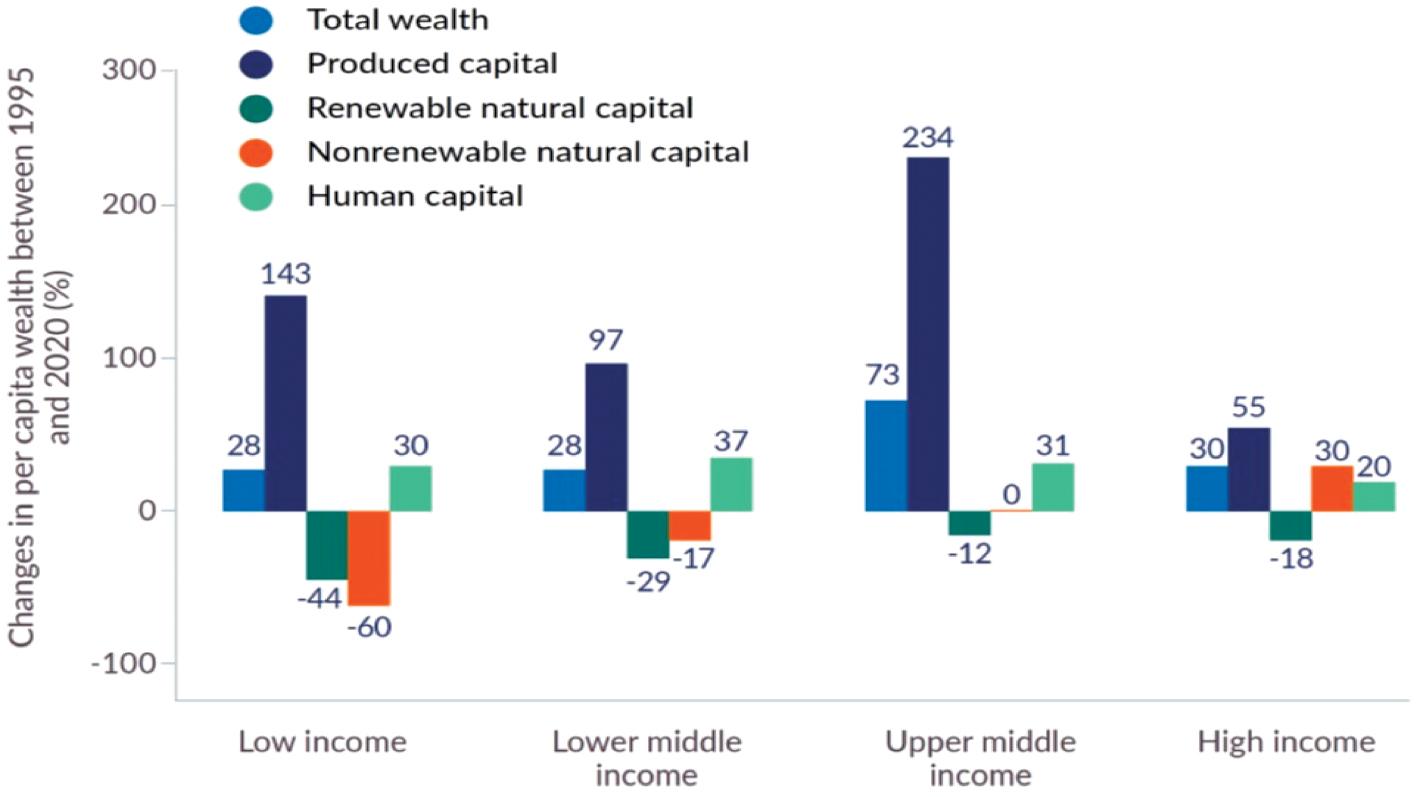

To assess the dynamics behind these capitals, World Bank data are the most comprehensive available, even if many minerals (e.g. diamonds and platinum) are not yet incorporated (Bond and Basu 2021). Recent findings in a Changing Wealth of Nations (CWON) study confirm a 60% per person decline in non-renewable natural capital from 1995 to 2020 in low-income countries (most of Africa) and 17% in lower-middle income countries (World Bank 2024). The upper-middle income countries include Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (part of the BRICS intergovernmental organisation), which are often both agents of extraction and manufacturing intermediary traders. Most profits still go to high-income economies benefiting from royalties, copyrights, research and development and financing (Figure 1).

Change in wealth per capita, by income group and asset class, 1995–2020.

Source: World Bank 2024, 69.

Such calculations allow for the insertion of natural capital dynamics within a broader Adjusted Net Savings measure for each economy, one that also aims to account for pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. As a shortcoming, CWON makes the national state the unit of analysis (Lange, Wodon and Carey 2018), inappropriately due to the transnational scope of both unequal ecological exchange and ecocide, for pollution and greenhouse emissions do not respect borders. Moreover, an extremely unequal society – southern Africa has several of the world’s worst – is not a coherent ‘nation’, because of divergences in social reproduction responsibilities due to residual racism, settler-colonial legacies and a migrant labour system that has bedevilled large-scale mining as well as artisanal extractive industries. So, these data should be considered conservative.

‘The Right to Say No!’ to resource looting

There is abundant national-scale evidence – for example, in South Africa (Bond 2021, 2025) – that confirms the net loss of national wealth due to inadequate compensation for the factors discussed above. Extracting non-renewable resources without regard for depletion, pollution and emissions occurs under conditions of super-exploited labour (with the highly gendered and geographical implications of migrancy). The adverse wealth effects should lead any objective observer to question the sustainability of contemporary mining, even using the mainstream definition of Gro Harlem Brundtland for the United Nations (1987) – ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ – augmented by the environmental-economic Hartwick Rule for reinvestment of the income proceeds from natural capital depletion.

Once depletion and other factors are considered, it is clear that the current emphasis on extractivism within the mode of production leaves many societies – 88% of sub-Saharan Africa according to the World Bank (2014, vii) – much poorer. Mining and fossil fuel revenues are not reinvested in adequate productive capital or education but instead externalised to foreign-headquartered mining houses or frittered away by local elites. The same is true across most of the African continent. Even the most obvious and oft-praised exception, Botswana, has not broken free of constraints associated with its primary raw material dependency, in part because it has limited its ambitions to a partnership with De Beers within the context of what is merely a resource-nationalist agenda.

Many if not all of the critiques of resource nationalism above are ignored by proponents, including the hosts of a recent Canadian conference held at York University in 2024. The tragedy therein is that, in part because the deeper critique is not contemplated, the only oppositional public-interest forces noticed by Caramento, Saunders and Larmer (2023, 354) are of a mildly reformist character:

Local communities surrounding mine sites have sought greater employment opportunities and the decentralised redistribution of fiscal receipts. Civil society organisations (CSOs) have advocated for greater transparency in the collection and allocation of resource rents and have encouraged African governments to counter mining companies’ efforts to evade taxation. CSOs have also sought to challenge the dislocation and environmental devastation of communities that reside near large-scale mining operations. Mining labour has sought less precarious work, improved and harmonised compensation packages, the domestication of mining employment, greater investment in skills development and increased workplace health and safety. Finally, artisanal and small-scale miners have sought to challenge property rights regimes and to secure better access to finance, machinery and services in support of expanded operations. Many of these constituencies were marginalised under neoliberal structural adjustment and the ‘good governance’ reforms of the 1990s and early 2000s.

This mild-mannered approach can be considered a ‘reformist reform’ (Gorz 1967 because, if successful, it will not only legitimise prevailing adverse systems of natural wealth depletion, local pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and social reproduction, by erasing most of the deeper analysis of the extractive industries above. In addition, such reformism ignores a ‘Right to Say No!’ movement increasingly insistent that, aside from minimal necessary material inputs within a context of global North ‘degrowth’, many minerals should be left underground. The further argument (and popular demand) typically missing in work by this team concerns ‘ecological debt’: that is, reparations are due from those institutions – including Canadian corporations, the Canadian state and wealthy shareholders – which have unfairly benefited from extractivism and its associated climate-related crises.

Given the net negative role of the extractive industries in Africa, surely the first step is to halt the damage. To that end, some resource-nationalist advocates suggest that mining – even fossil fuel extraction – can be reformed through initiatives aimed at shining a harsh spotlight on extractive-industry transactions to disinfect them of corruption and opacity. Establishment efforts through states and multilateral agencies include the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and Africa Mining Vision. Civil society groups with that limited agenda include the Soros-funded Publish What You Pay Network, Global Financial Integrity, Tax Justice Network, Eurodad and many other NGOs that are mainly disconnected from grassroots anti-extraction struggles.

Others take a much more critical approach, typically agreeing that there is a degree of minimally necessary mining that must occur for life to continue, but that contemporary consumption norms require degrowth rethinking because of enormous waste, socio-ecological and economic externalities, and unjust systems of accumulation by dispossession. The latter micro-struggles typically occur in ways that can periodically be brought together in coalitions, such as the Right to Say No! movement to leave minerals underground (in South Africa, supported by the Alternative Information and Development Centre and Mining Affected Communities United in Action), or the Africa-wide network Women against Destructive Extraction (WoMin) or, most significantly, the periodic World Social Forum ‘Thematic Forum on Mining and Extractivism’ (Bond 2018, 2025; World Social Forum 2023).

Covering up the Canadian pitfalls of resource nationalism

The activist critiques levelled against extractive industries operating in Africa are profound, because they address the class, race, gendered, generational and ecological damage done by corporations, global and local. That the Dutch East India Company, De Beers and Anglo American have in South Africa been largely replaced by local black-owned – or Chinese and Indian – mining houses (with Russians and Brazilians making an occasional entry) makes no difference to activists. Their ability not only to marshal data, but also to articulate why resource extraction amounts to looting, grows as they learn in the course of their battles, win partial victories (or suffer losses) and, step by step, generate a very different philosophy to govern future state–society–nature relationships (Bond 2025).

For activists opposed to such extractivism, one question passes from history to the present to the future: how to best argue for their rights to collective reparations for unequal ecological exchange, while continuing present struggles for environmental justice that entail the Right to Say No!, especially in cases where the extractive industries cause violence, such as most of those noted above. But simultaneously they are subconsciously or sometimes openly considering the rights of their descendants to have access to natural resources. To succeed, it appears that all three temporal settings (past, present and future) are required as fields of struggle, simultaneously. They should be backed by lawyers, ideally, but ultimately their campaigns must be won not in the courts but in the hearts and minds of society.

Particular forces in the case sites in society discussed above may well generalise their Right to Say No! to the global scale, as attempted in 2018 in Johannesburg and 2023 in Semarang, Indonesia in the Thematic Social Forum. Yet the leading resource-nationalist NGOs and researchers typically remain uninterested. As an exception, this 10-word mandate is located at the outset of Publish What You Pay’s impact report on its 2025 strategic vision: ‘natural resources are stewarded responsibly for current and future generations’ (Publish What You Pay 2024, 4). Yet, that rhetoric aside, none of the ways of making such a sentiment actionable discussed above appear to be on the network’s radar screen (and nor is extended social reproduction in cases of labour migrancy).

With respect to leading resource-nationalist researchers, the Canadian project referred to above also shows no interest in anti-extractivist movements, judging by the lack of mention – much less sustained study – of their existence, and of their principles, analyses, strategies, tactics and alliances. Yet Canadian mining houses represent some of the most predatory institutions on earth, with widespread revolts against their operations. Admitted the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (2023), ‘Canada is home to an estimated 60 percent of the world’s mining companies. They operate in all corners of the globe, including countries where mining activities have been linked to human rights violations.’ James Yap observes that Canadian mining companies have:

acquired a particularly bad reputation globally for causing serious human rights abuses … Six UN treaty bodies have specifically called out Canada for not doing more to ensure that its companies comply with international human rights and environmental standards. (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation 2023)

In another study, EarthRights International, Mining Watch Canada and the Human Rights Research and Education Centre Human Rights Clinic at the University of Ottawa (2016, 1, 3) submitted a report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, observing:

Canada’s mining companies are involved in such abuses and conflict more than any other country’s. Canada has been supporting and financing mining companies involved in discrimination, rape, and violence against women in their operations abroad, when it should be holding those companies accountable for the abuse … A study from 2009 found that since 1999, Canadian mining companies were implicated in the largest portion (34%) of 171 incidents alleging involvement of international mining companies in community conflict, human rights abuses, unlawful and unethical practices, or environmental degradation in a developing country. Of the Canadian-involved incidents, 60% involved community conflict, 40% environmental degradation, and 30% unethical behavior.

As Yves Engler (2021) summed up:

Canadian mining firms are mired in corruption and human rights abuses around the world … Pick almost any country in the Global South, from Papua New Guinea to Ghana, Ecuador to the Philippines, and you will find a Canadian-run mine that has caused environmental devastation or been the scene of violent confrontations.

To cover up this record, Engler (2021) continues,

Justin Trudeau has reneged on pledges to regulate them and end the abuses … The Trudeau government has channeled more than $100 million in assistance for international projects whose real purpose is to support mining. Those projects often come with sanitising, euphemistic titles such as ‘West Africa Governance and Economic Sustainability in Extractive Areas’, ‘Enhanced Oversight of the Extractive Industries in Francophone Africa’, and ‘Enhancing Resource Management through Institutional Transformation in Mongolia’.

And in what appears to be the same sanitising spirit, for Saunders (2020) the project of resource nationalism can apparently facilitate the (research-funder) Western state’s ‘regulatory’ role in legitimising corporate investment in Africa:

Canada is one of the major international investors in African mining. Its investments in African mining in fact increased tenfold in the first decade of the 2000s, so the [Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council] Insight grant looks at the experience of Canadian miners in Africa … and encouraged them in ways which would improve the relations with local hosts, which would boost the developmental outcomes in terms of skills training, transfer of skills and technology, and better corporate social responsibility overall. So we’re looking … at the various ways in which the new Canadian regulations have encouraged and elicited better behavior, but also ways in which the Canadian measures have enabled host countries and host communities and local businesses to demand and receive better deals, a better share of revenues, and a bigger piece of local content and provisions procurement from Canadians … There’s been a real wave in the last 10 to 15 years of resource nationalism, pushed from below as people have realised that in the commodities boom where mineral prices have gone up the local benefits have been minimal so this has led to a political response … The focus is more on building research capacity and policy engagement with local governments and with continental mining regimes through the Africa Mining Vision and it’s about building new young scholars and their capacity and then their engagement with research but also with policy making processes.

Conveniently for Canadian mining capital, the Africa Mining Vision makes the dubious point – unsupported by evidence – that ‘arguably the most important vehicle for building local capital are the foreign resource investors with the requisite capital, skills and expertise’ (African Union 2009, 22). Civil society critics include ActionAid, a Johannesburg-based international donor agency with strong connections to local anti-extractivist movements like Mining Affected Communities United in Action. After eight years of observing the Africa Mining Vision, ActionAid South Africa (2017, 3,19) expressed disgust because of its orientation to:

domesticating old European universalising ideas of domination and control. Thus the AMV [Africa Mining Vision] succeeds in replicating old colonial extractivist models which have historically and contemporaneously produced extreme inequality … The neo-colonial models of extracting Africa’s mineral and natural resources have resulted in pockets of obscene wealth and vast swathes of extreme poverty while a growing body of evidence suggests that much of the wealth extracted from Africa is realised outside of the continent … By ramping up and promoting models of maximum extraction, the AMV once again stands in direct opposition to our own priorities to ensure resilient livelihoods and securing climate justice.

If such critiques of the extractive industry’s wealth depletion, local pollution, global greenhouse gas emissions and super-exploitative social reproduction processes have merit, then new capacity building might be essential for Canadian scholars who never contemplate such a research skills set. And if these critiques lead to the conclusion that Canadian mining houses – along with their Western and BRICS brethren – are so predatory and such a source of systemic underdevelopment, then surely, building new young scholars to engage with – and support (not ignore) – anti-extractivist movements makes more sense.

Would the Canadian government fund such work? Probably not. Should progressive Canada-based scholars (like Caramento and Saunders) therefore do the bidding of state and mining capital by entirely neglecting some of the mostly costly features of extractive industry underdevelopment in Africa, as well as the social movements fighting to leave non-renewable resources underground? Definitely not.

Otherwise, Fanon’s (1961) complaint – about ‘the unpreparedness of the educated classes, the lack of practical links between them and the mass of the people [and environment], their laziness, and, let it be said, their cowardice at the decisive moment of the struggle’ – will be invoked as forcefully as the times demand. This is an especially serious complaint when directed against those who stumble into the pitfalls of resource-nationalist consciousness, because in the process they simply erase both the vast costs of capitalist extractive industries and the many Right to Say No! critics who want to see the back of them.