Background

Hepatic hemangioma (HH) is the most prevalent benign hepatic tumor in the general population with an incidence ranging from 0.4% to 20% [1]. HH is described, histologically, as dilated vascular lesions covered by a single endothelial layer, usually septated with fibrous tissue accompanied by high collagen content regions [2] and a blood supply acquired from a branch of the hepatic artery [1,3].

It has been classified histologically as cavernous, capillary, or sclerosing. [1,3,4]. The exact pathophysiology behind its development remains unknown [4].

Its clinical course is predominantly benign, and it is found incidentally through imaging studies with a diameter ranging from 1 mm to 3 cm [3,4]. Classification can be based on its diameter as small (<5 cm), large (5-10 cm), or giant (>10 cm) [5]. Usually, lesions do not keep growing, therefore, after their incidental asymptomatic discovery the development of later complications is considered unlikely [3].

Complications associated with this tumor are infrequent and are mainly related to the mass effect exerted by the tumor, for instance presence of pain and/or bleeding due to rupture [4,5]; however, the Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS) has been described as a severe complication.

KMS, which is mainly reported anecdotally through case reports, is more frequently associated with pediatric populations, although even in pediatrics is rare, with an incidence <0.07/100,000 inhabitants [2,6,7]; the exact incidence in adults is unknown [2]. KMS characterized by severe thrombocytopenia associated with coagulopathy that behaves similarly to disseminated intravascular coagulation [2,4,6]. The importance of its timely diagnosis and treatment lies in its severity and high mortality.

Here, we describe a case report of KMS as a complication due to a giant HH.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old female patient, previously diagnosed with hypothyroidism, was admitted with an earlier history of liver tumor found incidentally through ultrasound by a gynecological approach. No relevant family history was referred by the patient and her family. Later, she developed abdominal distention, petechiae, and prominent hematomas with minimal trauma.

For the initial approach, laboratory studies, core needle biopsy, and computed tomography (CT) were performed. Laboratory results showed normochromic normocytic anemia with hemoglobin of 5.8 g/dl, thrombocytopenia with 73,000 platelets, prothrombin time 14.6 seg, International Normalized Ratio 1.32, and fibrinogen of 131 mg/ dl.

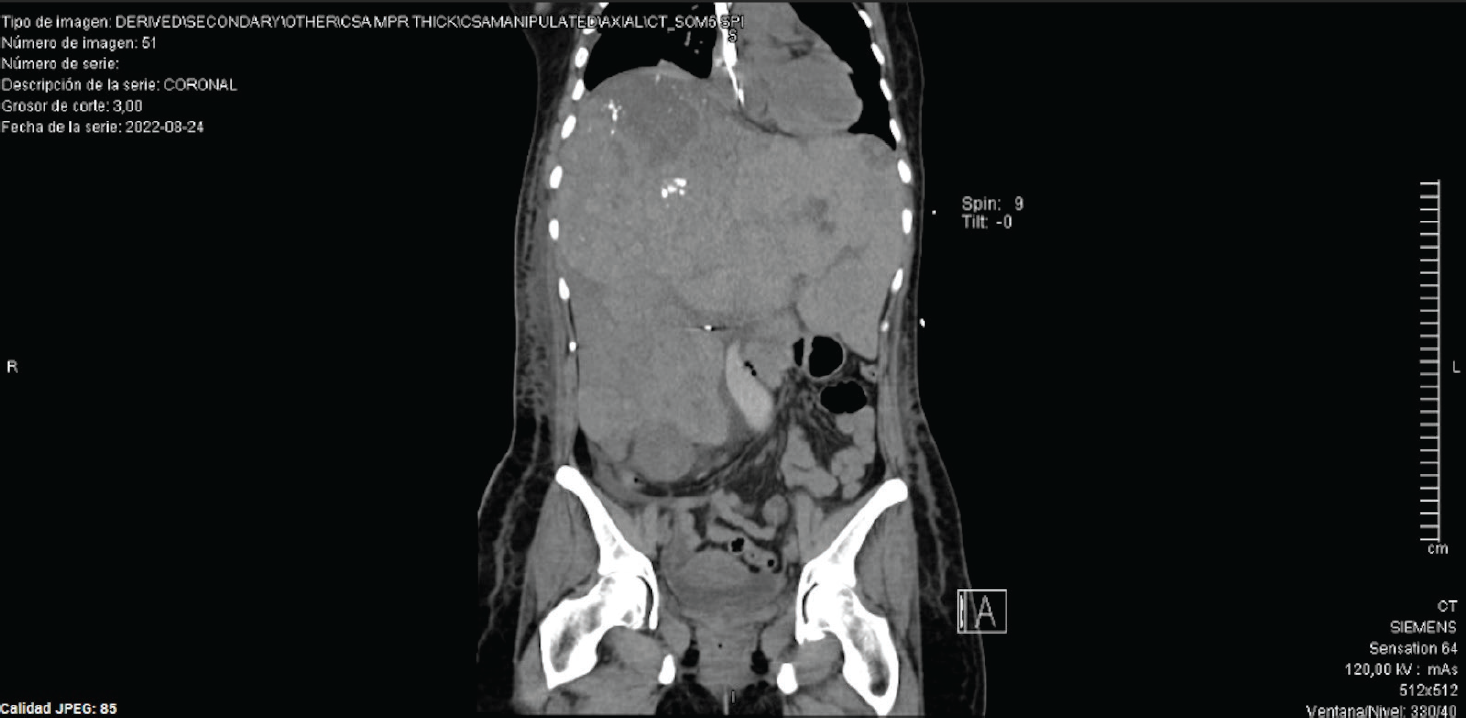

Coronal slide of an abdominal CT. A hepatic gland with morphology distorted, increased in size, heterogeneous densities, multiple nodular lesions, bigger lesion on segment VII, presence of some calcifications.

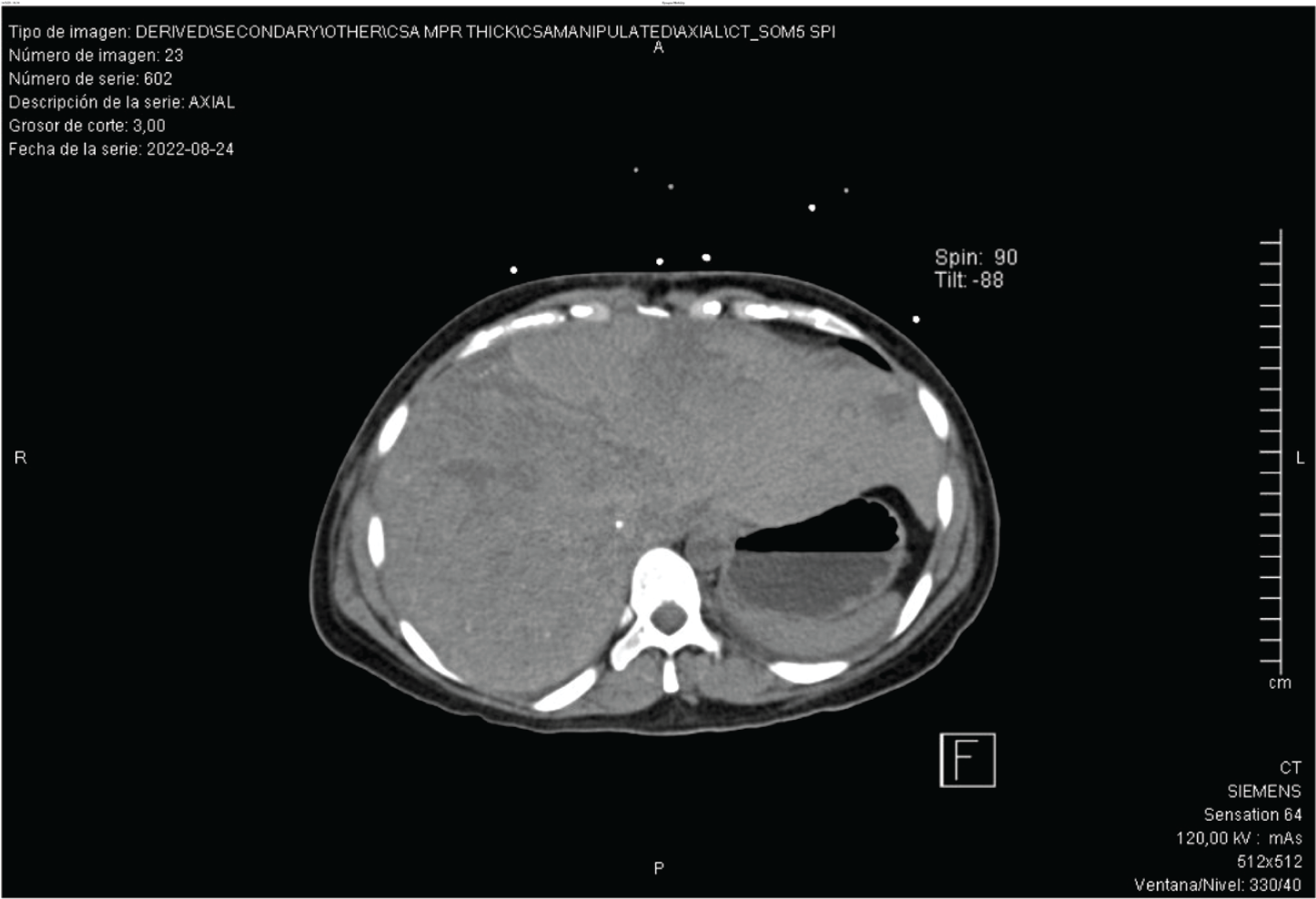

Axial slide of an abdominal CT. Presences of a hepatic gland occupying almost all the abdomen cavity, presence of hepatomegaly, and stomach in the left posterior side.

Liver core needle biopsy indicated a histopathological diagnosis of HH; abdomen CT exhibited an increased size of the liver gland, with a maximum axis of 29 cm, as well as multiple nodular lesions of greater density; the larger lesion was found in segment VII with a dimension of 10 × 13 cm (Figures 1 and 2).

Initial management was performed through erythrocyte concentrate transfusion without presenting any improvement in hemoglobin levels even though no bleeding source was found. Confirmation of hemolysis was done with elevated total bilirubin (total bilirubin: 2.04 mg/dl, indirect bilirubin: 1.81 mg/dl), high reticulocyte count (3.80%), and lactate dehydrogenase (370 U/l).

Intra-arterial chemoembolization of HHs was performed, continued by plasmapheresis transfusion and subsequent administration of pooled human plasma. Despite blood product usage, she continued with thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy due to consumption. Later findings showed a hematological deterioration from the baseline at the admission, with platelet levels of 64,000, prothrombin time of 15.8 seconds, International Normalized Ratio of 1.42, and fibrinogen of 158 mg/dl.

Other possible etiologies were ruled out as there were no data of systemic inflammatory response, neurological alterations, fever, or alterations in liver function tests, renal function tests, ADAMSTS13 metalloproteinase enzyme levels, procalcitonin or plasma leukocyte levels.

In the clinical context of a Giant HH (diameter >10 cm) [4] with data of thrombocytopenia, consumption coagulopathy, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia with no other possible etiology, a diagnosis of KMS was made.

Discussion

This case report presents a female patient with multiple HHs (the most common benign liver tumor in the general population) [1,8], one of them with a dimension of 10 × 13 cm. This case matches with the principal findings of the KMS [2,4,6,9,10] reported in the literature that was consulted for this article, this patient presents severe thrombocytopenia associated with a consumptive coagulopathy in the presence of a Giant HH that could explain the pathophysiology of this Hematological alteration [2,4]. During the development of this case report, several limitations were encountered related to the limited information available on KMS in Adults.

Conclusion

The HH is usually asymptomatic and with dimensions that do not exceed 3 cm in its maximum axis, however, given the severity of KMS, it is important to take this possible etiology into account, the timely diagnosis of this deadly complication is crucial to improve the prognosis. In the case presented, the diagnosis was made by integrating clinical data, laboratory, histopathological, and cabinet studies. We conclude that this pathology requires further investigation, especially with the treatment, since there is not a definitive consensus, and this pathology is strongly related to fatal outcomes.