Background

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (SCA) of the small intestine is a rare condition and is mostly reported to involve the distal small intestine. The tumor can be either grossly polypoid or endophytic with central ulceration and an average size of about 7 cm at diagnosis [1]. Although previously described using different terms, such as pleomorphic carcinoma and carcinosarcoma, SCA is the universally accepted term based on the morphology and immunohistochemical characteristics of the tumor [2]. It is considered a more aggressive and metastatic tumor compared to other small intestinal tumors [3]. This case describes a male patient in his 70s with recurrent passage of melena and limitations encountered with management.

Case Presentation

A male patient in his 70s with a background history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), presented to the general practitioner with 4 weeks of nausea, heartburn, left upper abdominal pain, and passage of black tarry stools. Blood showed hemoglobin (Hb) - 80 g/l, mean corpuscular volume - 71 fl, low transferrin saturation; and an assessment of flare of GORD and iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was made. A referral was made to the hospital where he had an urgent upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy which revealed no bleeding source or any abnormal findings; treated with intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI), blood transfusion, and discharged home on oral PPI.

He subsequently presented to the ambulatory care unit a week later with reduced exercise tolerance, abdominal pain, ongoing passage of black tarry stool, and weight loss. Abdominal examination revealed left upper quadrant tenderness and black tarry stool on rectal examination. The rest of the history and systems examination were unremarkable.

Blood at this time showed Hb of 103 g/l, iron - 4 umol/l, and transferrin saturation - 8.8%. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed an irregular thickening of the jejunal wall at its proximal part (Figure 1), total length of about 10 cm. Adjacent surrounding strandings and lymph nodes were also noted. No convincing contrast blush was noted in the bowel lumen during the arterial or venous phases to suggest active bleeding. Given the presenting symptoms and findings on imaging, differential diagnoses included lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, or gastrointestinal stroma tumor (GIST).

The patient was booked in for an emergency laparotomy where he had small bowel resection and bowel anastomosis. Intraoperative findings showed a small bowel tumor and a walled-off abscess. The sections of the bowel showed a large irregularly polypoid tumor with extensive necrosis and hemorrhage measuring 100 mm to the greatest extent. The tumor extended to the serosa grossly over the area of perforation.

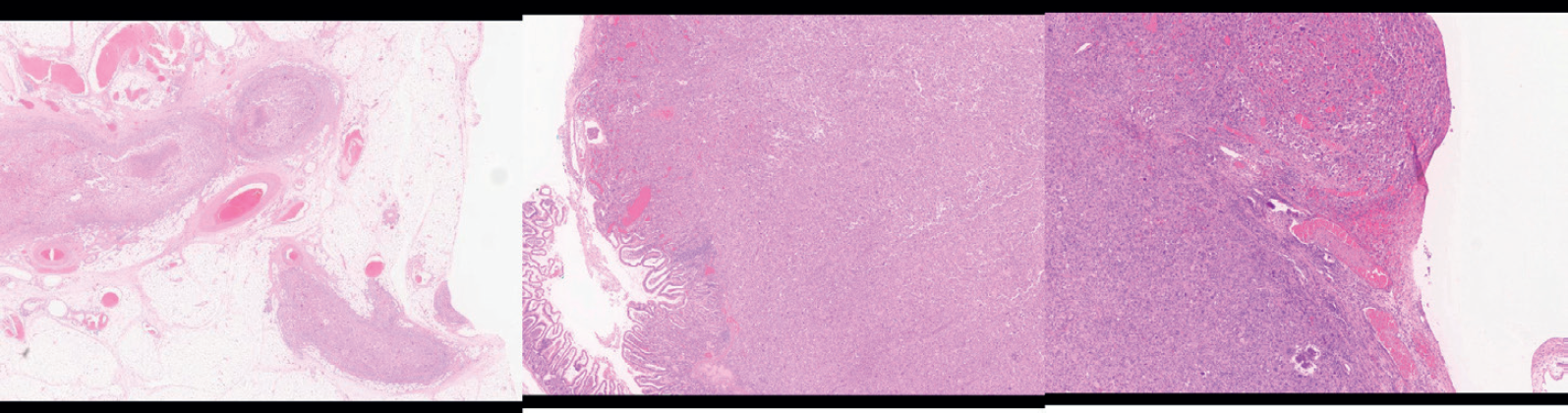

Microscopically, the tumor exhibited malignant features. The tumor was described as an ulcerated, polypoid high grade poorly differentiated to undifferentiated tumor with focal areas showing rhabdoid morphology which infiltrated the muscularis propria with involvement of serosal layer; and extensive lymphovascular space invasion (Figure 2a-c), both intra-and extramural. Morphologically, there were no epithelial areas, and the tumor was 100% mesenchymal. The mesentery contained several lymph nodes, 13 out of 13 which showed evidence of malignancy.

The diagnosis was confirmed by the morphology and immunohistochemistry (hematoxylin and eosin staining) as poorly differentiated SCA - stage: pT4 N2 (stage IIIb). Other markers such as the AE1/AE3 (a broad-spectrum cytokeratin), CAM 5.2 (a low molecular weight cytokeratin), and S100 were also positive (Figures 3a, b, c). Desmin, SMA and CD34 were negative.

(a-c) Haematoxylin and eosin staining showing evidence of lymphovascular invasion, erosion of mucosa and serosa of the bowel wall respectively.

At 2 months postsurgical resection of the tumor, the patient reported improvement in his symptoms and was able to carry out his daily walks without fatigue. Following the multidisciplinary team meetings, the decision was for heightened surveillance with four monthly CT scans for the first year, and six monthly thereafter.

Discussion

The four most common malignancies of the small intestine are adenocarcinoma, lymphomas, neuroendocrine tumors, and sarcomas [4]. SCA of the small intestine in itself is described as rare, affecting middle-aged and elderly patients, and most cases involve the ileum, jejunum, and duodenum in that order, with a higher prevalence in male patients [2]. This is similar to the report by Zhu et al. [5] with a male-female ratio of 1.46:1 and a mean age of 60 years. The report however revealed a higher incidence of the tumor involving the jejunum, followed by the ileum, and very rarely, the duodenum. Worldwide, about 20 cases of SCA of the jejunum have been reported, and although there have been reports of SCA involving other body systems in the United Kingdom, none has been previously reported involving the jejunum. Zhang et al. [6] reported on the common presenting symptoms in these patients, anemia being the most common, followed by abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal mass, weight loss, and fatigue. This is similar to the presenting symptoms in this case. Other symptoms that have been described include cancerous bleeding, tumor perforation, and acute peritonitis [7-9]. The array of nonspecific symptoms and numerous differential diagnoses are likely to make an early diagnosis difficult. Zhu et al. [5] in their study of the molecular pathogenesis of SCA of the jejunum concluded on the possibility of a number of genetic alterations and key driver genes that may be similar to other malignancies including large intestine adenocarcinoma, melanoma, laryngeal squamous cell cancer, and transitional cell carcinoma.

On histology, SCA can be described as having a monophasic pattern, in which case there are little or no epithelioid areas but rather the predominance of mesenchymal tissue or biphasic pattern which contains a mixture of epithelioid and mesenchymal tissue [3]. Definitive diagnosis of SCA is made following the use of a variety of immunohistochemical biomarkers [2,10,11] which aid in its differentiation from other malignancies. A negative CD34 rules out a possible GIST and epithelioid angiosarcoma, and a negative smooth muscle actin and desmin exclude leiomyosarcoma.

As small intestinal tumors can present with nonspecific symptoms, there is a requirement for a thorough diagnostic evaluation. The UGI endoscopy in this case, with the limitation of no visualization beyond the first part of the duodenum, revealed no bleeding source despite the patient’s symptoms and the presence of IDA. The European guidelines recommend the use of capsule endoscopy in cases where small intestinal tumors are suspected, and IDA remains unexplained [12]. Though capsule endoscopy has improved the diagnostic yield of these tumors, however, it cannot be used to obtain tissue for diagnosis, thus, a limiting factor in this case. Double balloon enteroscopy is described as an advanced endoscopic procedure with the advantage of visualization of the entire small bowel and can allow for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures [13]. The distance to the nearest center offering this procedure, including the constraints of referrals and/or waiting lists, discouraged its use. These limitations informed the decision to undergo an emergency laparotomy for tissue biopsy.

CT scan of the head and thorax showed no evidence of distal metastasis, however, the most common sites for metastases documented are the lung, distant lymph nodes, and liver, with occasional involvement of the brain and pelvic bones. Jejunal SCA is described to have an extremely poor prognosis and the average survival time is a few months to 3 years of diagnosis, with a median survival time of 7 months [2,5,6]. Being a rare disease, a number of multidisciplinary team meetings held to discuss treatment options. There is no official treatment guideline for SCA, but tumor resection by surgery is said to be the mainstay of treatment, as responses to chemotherapy and radiation treatment have been extremely poor. In some cases, adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy were administered, but there were no improvements in survival [2,13]. It was concluded that radical surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy and close follow-up is therefore important management strategies [14].

In conclusion, SCA of the jejunum is a rare and extremely aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis. There is often a delay in diagnosis, thus, early diagnosis through detailed evaluation can improve prognosis.