Background

Over the last decade, a deeper understanding of the interactions between the immune system and tumor microenvironment has revealed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as a promising treatment for a range of cancer types including lung, kidney, head and neck, and melanoma.

Notwithstanding the added survival benefit for cancer patients, diverse and unpredictable immune-related adverse effects (irAEs) have come alongside ICI treatments. The most common irAEs are transient and self-limited and include dermatologic toxicity, endocrinopathies, colitis, pneumonitis, and liver toxicity [1]. In fact, IrAEs can potentially involve any organ and may lead to significant morbidity and, to a lesser extent, mortality [1]. Nevertheless, irAEs have been positively associated with a survival benefit [2]. Neurologic-related irAEs are rare, representing 1% of the total of irAEs [3]. A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis, which included 39 trials, showed that patients treated with ICIs are less likely to develop neurologic adverse events compared with other cancer medications, particularly cytotoxic chemotherapy [4]. Within the ICI group, the large majority of neurologic adverse events were reported with anti-PD-1/PDL-1 agents (70.4%), followed by anti-CTLA-4 agents (25.3%) [4]. Among the neurologic-related irAEs, the myasthenic syndrome has been associated with a worse prognosis [5]. Early recognition and prompt treatment are critical for reducing the burden associated with irAEs.

We herein report an extremely rare case of an overlap syndrome of myositis and probable myasthenic syndrome, complicated with myocarditis in a melanoma patient.

Case Presentation

A 75-year old male patient with B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) wild type stage IIIA melanoma presented to the accident and emergency department with a 1-week complaint of vision difficulty and progressive weakness affecting mainly the neck and lower limbs. The patient’s wife noted that he had also developed drooping eyelids. This patient had been recently diagnosed with melanoma with lymph nodes metastasis and was subject to wide local excision. He had received his first dose of adjuvant therapy with pembrolizumab 22 days prior to symptoms onset.

In the neurologic examination, he showed generalized hypotonia with weakness of the neck extensor muscles, mild dysarthria, and bilateral ptosis. Initial lab work revealed an elevation in transaminases alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase (AST 909 U/l, ALT 429 U/l) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH 1,274 U/l). A presumptive diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced myositis was considered, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) to immediately be started on 2 mg/kg of prednisolone endovenous (EV).

24 hours after the admission, clinical deterioration continued with fluctuating awareness and the onset of dysphagia with an urgent need for nasogastric intubation. Neurological examination showed ophthalmoplegia in vertical movements and significant ophthalmoparesis in horizontal ones. Bilateral ptosis with diparesis was also present with decreased power in neck extension and muscle power of 4/5 in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Scale of the 4 limbs. At this point, a significant elevation of creatine kinase (CK 10,222 U/l) was detected and a troponin I (TpI) peak of 11,195ng/l with a normal electrocardiogram was identified and interpreted as myocarditis in the clinical context of myositis.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was unremarkable. Lumbar puncture identified mild pleocytosis (13 cells/ml), with mononuclear predominance, negative results of herpes virus family polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Mycobacterium tuberculosis PCR, microbiologic examination and negative anatomo-pathologic examination. Electroencephalogram (EEG) excluded epileptic activity but showed marked lentification. Muscle biopsy showed a pattern of necrotizing and inflammatory myositis with T lymphocyte enrichment. Electromyography (EMG) findings, 2 weeks after the admission, were compatible with an axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, related to the immobilization and myopathy. A decremental response to the repeated stimulation was not observed.

After 3 days of progressive worsening of mental state, an acute respiratory failure episode occurred, and non-invasive ventilation (NIV) was required. Treatment was then switched to a 5-day course of 1,000 mg of IV methylprednisolone and a trend toward recovery was observed. After pulse therapy and because the patient maintained an intermittent need for NIV, a 5-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), 0.4 mg/kg, in association with 1 mg/kg of prednisolone was decided. Symptomatic treatment with pyridostigmine was also initiated, up to 60 mg PO tid. A progressive improvement of ventilation capacity was then observed with the patient tolerating spontaneous ventilation on day 3 of IVIG treatment.

Serology results came back negative for antibodies anti-acetylcholine receptors (anti-ARCh) and anti-muscle specific kinase (anti-MuSK) and positive for striated muscle antibodies. A clinical hypothesis of overlap of myositis with a myasthenic syndrome complicated by myocarditis induced by pembrolizumab was considered.

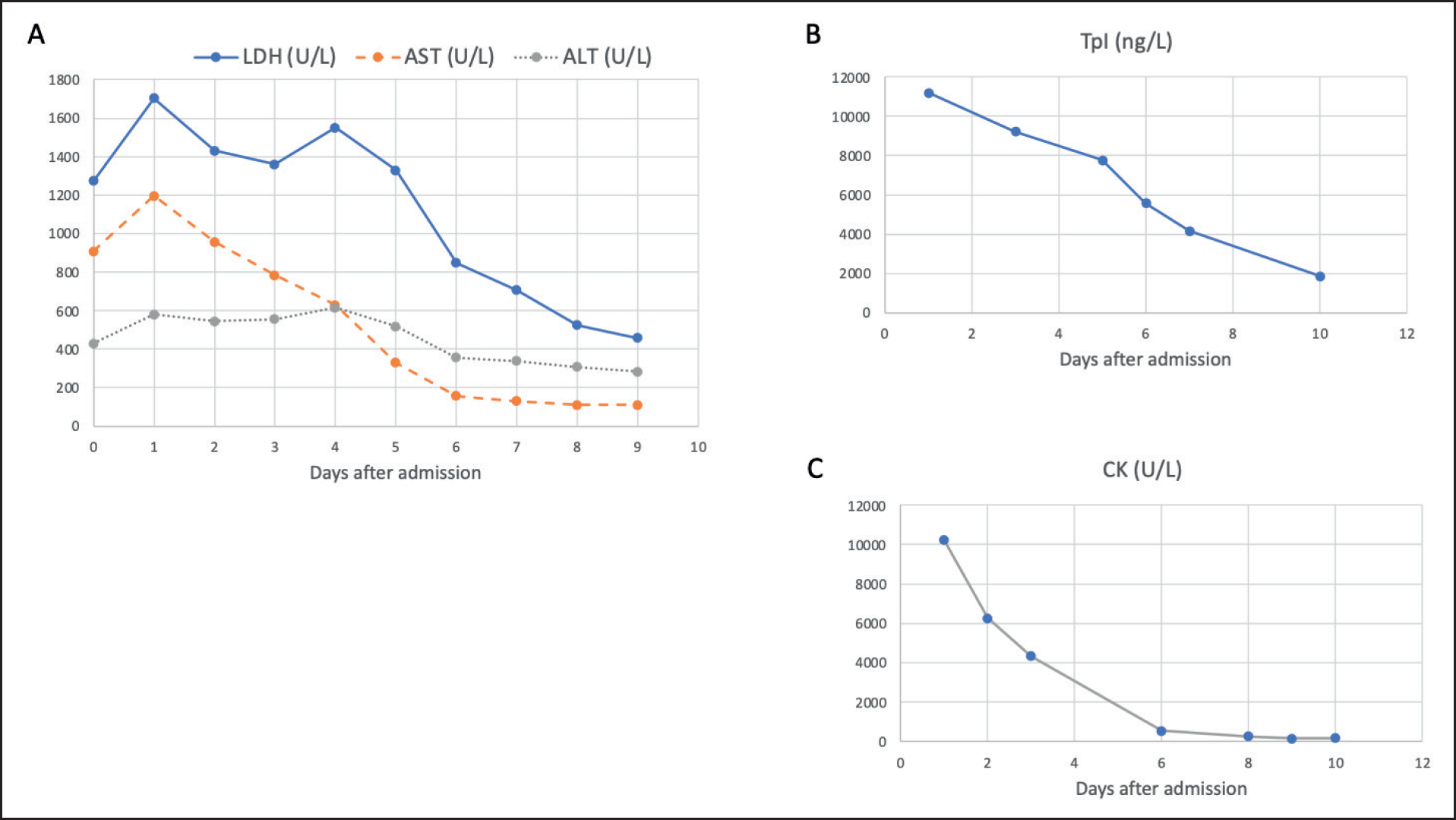

During the remaining time in ICU, an improvement in patient muscle strength was observed, except for oculomotor muscles. A lab downward trend in LDH, AST, ALT, CK, and TpI followed the clinical improvement (Figure 1).

The patient spent a total of 41 days in ICU under daily observation by a neurologist. Overall, ophthalmoplegia, myosis, and generalized hypotonia dominated the clinical picture.

Temporal evolution of biochemical parameters altered at time of admission. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CK, creatine kinase; and TpI, troponine I.

At the time of hospital discharge, on day 44 post-admission, the patient had partially recovered mobility and was able to maintain conversation for short periods. Dysphagia was still present and oral diet was ruled out. It was decided to keep steroids for 4 weeks and to start azathioprine. He was discharged to a long-term healthcare facility and a decision not to restart anti-melanoma immunotherapy was made.

At the 1-month follow-up of neurology appointment, exactly 2 months after hospital admission, the patient still presented mild dysarthria and dysphagia, ptosis, and needed assistance to walk.

Discussion

Despite the fact that ICI-induced neurotoxicities are uncommon, these phenomena are often severe and rapidly progressive, and clinical experience is still limited.

We reported a rare case of an overlap syndrome of myositis and myasthenic-like syndrome, complicated with myocarditis. Despite the absence of autoantibodies and EMG confirmation, we suspect there is a neuromuscular transmission defect because of the involvement of the ocular extrinsic muscles, which is very rare in inflammatory myositis. Additionally, the clinical picture with the absence of ocular movements, facial diparesis, dysphagia, and anarthria as well as respiratory failure and tetraparesis is the typical phenotype of a myasthenic crisis. Another important point is that there was a partial response to pyridostigmine.

Within the rarity, pembrolizumab-induced myasthenic syndrome along with myositis has been only rarely described (Table 1).

In 2018, Hibino et al. [6] reported a case of myasthenic syndrome with myositis that developed during the second cycle of palliative pembrolizumab therapy for a patient with PD-L1 positive lung squamous cell carcinoma. The patient presented with visual abnormalities and drooping eyelids. Ptosis, diplopia, and neck weakness were identified. Laboratory findings revealed elevated CK and liver transaminases. The patient was initially treated with pyridostigmine, without symptomatic relief. The switch to systemic steroids yielded a complete resolution of neurological symptoms.

A fatal pembrolizumab-related case of superimposed myositis and myasthenic syndrome complicated with myocarditis in a 30-year-old patient diagnosed with a metastatic thymoma was reported by Konstantina et al. [7]. In this case, symptoms onset occurred only 3 days after the first administration of the immunomodulator with patient complaints of acute chest pain and proximal muscle weakness. Ptosis and diplopia were also identified, and lab work showed elevated CK, TpI, and transaminases. After receiving treatment with steroids, pyridostigmine, IVIG, and rituximab, patient was deceased on day 64 of hospitalization due to septic shock.

Another fatal case of the myasthenic syndrome and myositis induced by pembrolizumab was reported by Elkhider et al. [8] concerning a metastatic urinary bladder cancer patient. Two weeks after receiving the second treatment, the patient presented with rapidly progressive ptosis, diplopia, proximal muscle weakness, and swallowing difficulty. Ophthalmoparesis and weak neck flexion were also identified. Lab work showed elevated CK and negative anti-AChR antibodies. After receiving pyridostigmine, steroids, and plasma exchange with no significant improvement, death occurred on day 7.

In 2020, a report was published concerning another fatal case induced by pembrolizumab of myocarditis following an overlap syndrome of myositis and myasthenia gravis (MG) in an advanced upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma patient [9]. Severe fatigue and abnormal gait were present 5 days after receiving the second treatment. Clinical findings also included diplopia, bilateral ptosis, decreased tendon reflexes (brachioradialis, triceps, patellar, and Achilles), and iliopsoas and neck muscle weakness. Biochemical blood tests revealed elevations of CK, myoglobin, and TpI, with negative MG serology. The patient was put on steroids followed by plasma exchange but a worsening of myocarditis lead to death on day 17.

Hayakawa et al. [10] published a case of MG with myositis induced by pembrolizumab in a patient with metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Generalized weakness and right ptosis were reported 3 days after the second treatment. Neck muscle weakness was also noticed. Lab work showed elevated CK and negative MG antibodies. Treatment with pyridostigmine was initiated but rapidly discontinued due to severe digestive complaints. The patient was kept under steroid treatment and discharged on day 45 with a complete resolution of the neurological symptoms.

Another case of pembrolizumab-induced myasthenic syndrome with myositis was published by Todo et al. [11] concerning a patient with bladder carcinoma that progressively developed diarrhea, erythema multiforme, ptosis, and diplopia 12 days after the first treatment. Blood tests showed elevated CK, TpI and negative MG antibodies and early treatment with steroids was effective. Interestingly, the tumor significantly shrunk and remained small without any further treatment as of 201 days after a single injection of pembrolizumab.

In 2021, Tian et al. [12] reported a case of a patient diagnosed with urothelial carcinoma that developed MG and ocular myositis 16 days after receiving the first treatment of pembrolizumab. Physical examination revealed ptosis and limited extraocular muscle movements. Laboratory showed elevated CK and transaminases. A gradual resolution of symptoms was achieved with steroids and pembrolizumab was restarted with low-dose oral steroids.

A more recent case of myositis and myasthenic syndrome related to pembrolizumab was published by Sanchez-Sancho et al. [5]. A patient diagnosed with metastatic undifferentiated liposarcoma under treatment with pembrolizumab developed ptosis, diplopia, myalgia, dysphagia, and dysphonia 6 days after the first injection of the immunomodulator. Along with a TpI elevation, a cytolysis pattern with high transaminases, CK, and LDH was also observed. Steroids and IVIG lead to a good clinical evolution. The patient was decided to be kept on IVIG 1/month.

| REFERENCE | PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS (GENDER/AGE) | CANCER TYPE | PEMBROLIZUMAB TIMING AT SYMPTOMS ONSET | SYMPTOMS AT PRESENTATION | OTHER PHYSICAL EXAMINATION FINDINGS | LAB FINDINGS | TREATMENT | OUTCOME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hibino et al. [6] | Male, 83 | Lung | 38 days after first administration (second cycle) | - Narrowing visual field - Eyelids fatigability | - Ptosis - Restricted eye movements - Diplopia - Neck extensor weakness | CK 4,361 IU/l AST 269 IU/l ALT 222 IU/l Anti-AChR - Anti-MuSK - | Pyridostigmine steroids | Complete resolution of neurological symptoms |

| Konstantina et al. [7] | Female, 30 | Thymoma | 3 days after first administration | - Acute chest pain - Proximal muscle weakness | - Diplopia - Ptosis | Elevated CK, TpI, transaminases Anti-AChR + | Steroids pyridostigmine IVIG rituximab | Death at day 64 (septic shock) |

| Elkhider et al. [8] | Female, 75 | Bladder | 36 days after first administration (second cycle) | - Double vision - Swallowing difficulty - Proximal muscle weakness | - Bilateral ptosis - Ophtalmoparesis - Weak neck flexion | CK 7,500 IU/l Anti-AChR - | Pyridostigmine steroids plasma exchange | Death at day 7 |

| Matsui et al. [9] | Male, 69 | Bladder | 26 days after first administration (second cycle) | - Severe fatigue - Abnormal gait | - Diplopia - Ptosis - Decreased tendon reflexes - Iliopsoas and neck muscles weakness | CK 3,887 IU/l TpI 10,318 pg/ml Anti-AChR - Anti-MuSK - | Steroids plasma exchange | Death at day 17 |

| Hayakawa et al. [10] | Female, 84 | Bladder | 24 days after first administration (second cycle) | - Ptosis - Lower extremities weakness | - Neck muscle weakness | CK 828 IU/l Anti-AChR - Anti-MuSK - | Steroids pyridostigmine | Complete resolution of neurological symptoms |

| Todo et al. [11] | Male, 63 | Bladder | 12 days after first administration | - Ptosis - Diplopia - Diarrhea - Erythema multiforme | CK 3,385 IU/l TpI 372 pg/ml Anti-AChR - Anti-MuSK - | Steroids | Putative pathological complete remission | |

| Tian et al. [12] | Female, 75 | Bladder | 16 days after first administration | - Ptosis | - Limited extraocular muscle movements | CK 4,817 IU/l AST 163 IU/l ALT 258 IU/l | Pyridostigmine steroids | Restarted pembrolizumab +PDN 15 mg bid |

| Sanchez-Sancho et al. [5] | Male, 63 | Liposarcoma | 6 days after first administration | - Diplopia - Ptosis - Lower extremities myalgia - Dysphagia - Dysphonia | AST 1,057 IU/l ALT 770 IU/l CK 14,448 IU/l TpI 18,353 ng/l Anti-AChR + Anti-MuSK - | Steroids IVIG | Good clinical evolution (IVIG treatment 1 day/month) |

The reported cases of co-occurring myositis with MG induced by pembrolizumab hold in common some important features: a) early symptoms onset, occurring mainly between the first and second cycle of treatment; b) a pattern of onset symptoms including vision deficits (diplopia, narrowed visual field), ptosis and muscle weakness (markedly involving neck muscles); and c) biochemical blood test showing elevated CK and liver transaminases with negative MG serology.

In several case reports, TpI was also found elevated in the context of myocarditis that, inclusively, resulted in a case fatality [9]. In the literature, the incidence of irAEs-related myocarditis is 1% with a median time of onset of 34 days after the first cycle of ICI and associated with a high fatality rate [13].

Also, in the majority of the case reports reviewed, autoantibodies related to inflammatory myopathy were negative, while anti-striated muscles were found in the majority of the patients. This pattern of double seronegative MG, also found in the case we herein report, seems to be common among irAEs [14]. In fact, it has been previously speculated that anti-striational antibodies could be used as potential diagnostic biomarkers for PD-1 myopathy [14]. Another important aspect is the fact that an elevation of CK has been observed several days before the onset of pembrolizumab-induced myopathy and CK levels were significantly higher in the patients with the severe form [14].

Gathering the information collected from the reviewed cases and from the case we herein present, we propose that, especially during the first two cycles of pembrolizumab and eventually of the other ICIs, patients should be closely monitored regarding complaints of fatigue mainly in limbs and neck, ptosis and visual field defects, eventually combined with lab monitoring of CK, LDH, aminotransferases, and TpI levels. A suggestive alteration could raise awareness of an upcoming irAE.

Regarding the treatment of neuromuscular irAEs, guidelines [3,15] suggest that therapy with PD-1 inhibitors should be withheld unless mild symptoms (grade 1). In the event of moderate symptoms treatment should be initiated with prednisolone 0.5-1 mg/kg (grade 2). High-dose steroid therapy with oral prednisolone (1-2 mg/kg) or i.v. equivalent should be used in the event of significant neurological toxicity, such as weakness severely limiting mobility, cardiac, respiratory, and dysphagia. Additionally, plasmapheresis or i.v. IG may be required in the treatment of myasthenia and Guillain Barré syndrome. An absolute contraindication to restarting PD-1 inhibitors is life-threatening toxicity, including myocardial involvement.

Conclusion

Severe irAEs can appear early, progress rapidly, and involve multiple systems and organs, resulting in high morbidity and fatality. A high level of vigilance is needed, as early recognition and treatment are keys to a successful outcome.

What is new?

An extremely rare overlap of inflammatory and necrotizing myopathy with superimposed myasthenia-like syndrome related to immunotherapy, plus a comprehensive literature review with eight similar reported cases whose data was assembled in a table allowing the identification of a clinical and laboratory pattern that precedes the manifestation of the described syndrome.