Background

Hemoptysis is defined as the expectoration of blood from the tracheobronchial tree. It is an alarming symptom and matter of concern for both the patient and the treating physician. Hemoptysis can be caused by various mechanisms depending on the underlying etiology [1]. A detailed history and thorough examination followed by a focused investigation are required for diagnosis. We report a case of descending aortopulmonary fistula (DAPVF) as the cause of recurrent hemoptysis in a 33-year-old female. To the best of authors’ knowledge, only very few cases of DAPVF as a cause of hemoptysis in adults have been reported in the literature.

Case Presentation

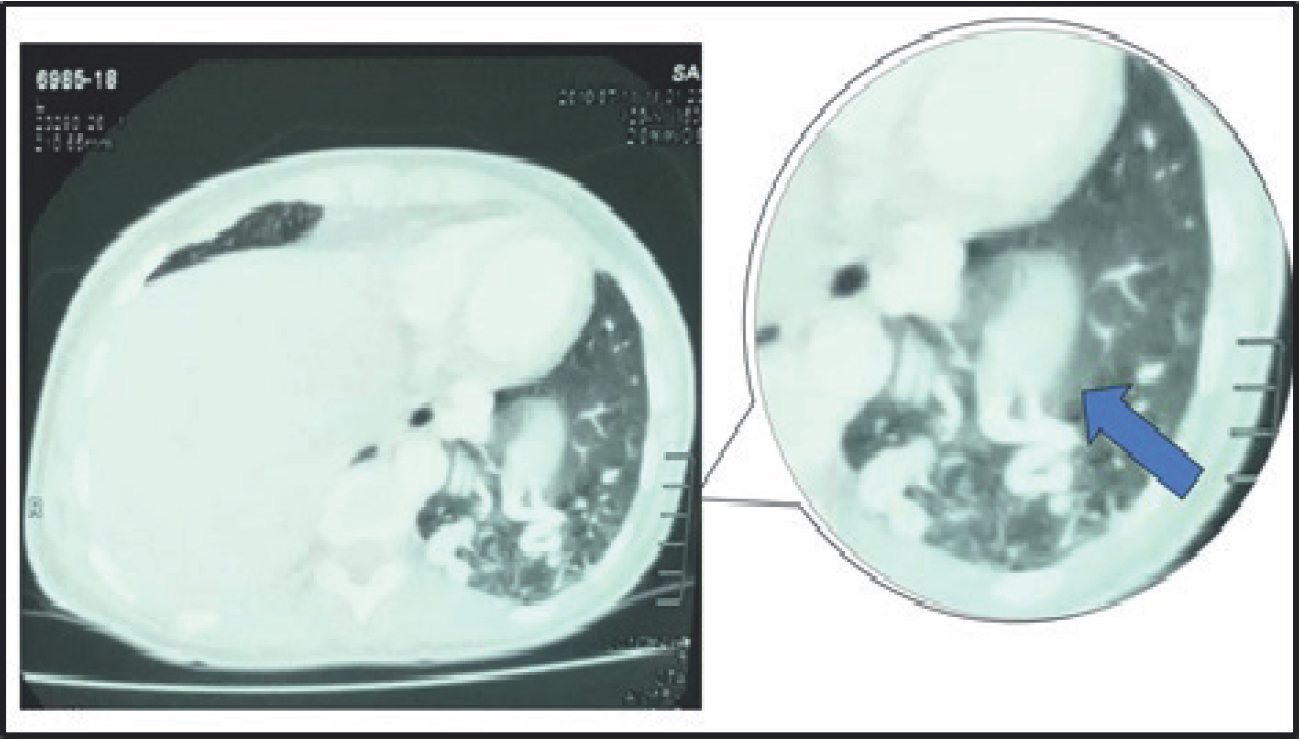

A 33-year-old female presented with the chief complaints of mild hemoptysis, 1-2 episodes/month for 2 years which increased to 3-5 episodes/month for the past 2 months. She was a non-smoker, and there was no history of thoracic trauma, anti-tubercular drug intake, hereditary disorder, and anticoagulant drug use. Menstruation had no effect on the episodes of hemoptysis. There was no other significant history, and on general examination, she had a pulse of 96/minutes, BP of 122/84, respiratory rate of 18/ minutes, and SpO2 of 98% at room air. Respiratory system examination was within normal limits. On cardiovascular system examination, a continuous murmur was heard over the fourth intercostal space along the left sternal border. Laboratory tests revealed that normal white blood cell counts were 8,980 cells/μl. Kidney function tests, liver function tests, random blood sugar, and rest biochemistry were also normal. A chest X-ray and echocardiography was done and found to be within normal limits with echocardiography showing a normal left ventricular systolic function and an ejection fraction of 64%. A chest X-ray and echocardiography had no changes suggestive of pulmonary hypertension. The patient was planned for contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the chest when she revealed that a previous CECT abdomen has been done at other centers for an unrelated complaint. On reviewing these CT films, some sections showed serpiginous structures consistent with enlarged vessels in the left lower lobe (Figure 1). Hence, CT pulmonary angiography was performed which showed an anomalous systemic artery arising from the descending aorta which was connected to the left inferior pulmonary vein representing the structure of DAPVF (Figure 2). An anomalous large vessel originated from the descending aorta and then descended below the diaphragm coursing along the left diaphragm before entering the left inferior lobe and finally to the left atrium via the inferior pulmonary vein. The three-dimensional reconstruction of the same is shown in Figure 3. The rest of the aorta was normal. The patient was referred to the department of cardiothoracic surgery for ligation of the fistula; however, the patient refused for any intervention.

Section of CECT abdomen showing serpiginous structures (arrow) consistent with enlarged vessels in left lower lobe of lung.

(A) CT angiography showing the anatomic structure and the course of the anomalous dilated vessel. An anomalous large vessel (#) originated from the descending aorta, then descended below the diaphragm coursing along the left diaphragm before entering the left inferior lobe and finally to left atrium via inferior pulmonary vein (black arrow). (B) Sagittal section showing the course of DAPVF. The anomalous systemic artery (*) arises from the descending aorta.

Discussion

Usually, the only communication between the systemic and pulmonary arterial systems is represented by the connection between the bronchial and pulmonary artery systems. The earliest descriptions of anomalous systemic to pulmonary communications dates to 1,777 [2]. These anomalous connections can be congenital or acquired [3]. Acquired causes mainly include aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, infective endocarditis, syphilitic aortitis, Marfan's syndrome, and trauma. The origin of the fistulae can be from a normal systemic artery, e.g., bronchial or internal mammary artery. On the other hand, the origin can be from an aberrant systemic artery arising from the aorta. The adjoining lung parenchyma may be normal or sequestrated in the latter case [4]. DAPVF is a rare congenital anomaly representing a left-to-left shunt in the absence of pulmonary involvement [5]. The left-to-left shunt is responsible for the presence of murmur. This shunt can cause the enlargement of the left atrium and left ventricle and, in due course, may lead to heart failure. Cardiac failure may be the presenting feature as described in some reported cases in children [5–8]. Very few cases of DAPVF as a cause of hemoptysis in adults have been reported in the literature [9,10]. In a review by Jariwala et al. [7] on anomalous systemic artery to pulmonary vein fistula out of the eight cases where the anomalous vessel originated from descending thoracic aorta, only one was reported in an adult. In another review by Yamanaka et al. [11] on cases of anomalous systemic arterial supply to normal basal segment of lower lobe, out of the 11 cases, where the anomalous vessel originated from descending thoracic aorta, only two had hemoptysis as one of the clinical manifestations. Hemoptysis is a consequence of persistently elevated venous pressure, resulting in segmental pulmonary arterial hypertension, which further leads to the rupture of proliferating and dilated vessels of the basal segments. In this case, although the patient had hemoptysis and murmur was present on cardiac examination, the etiology could not be established on preliminary investigations.

Conclusion

DAPVF is a rare congenital vascular malformation representing a left-to-left shunt, and cardiac failure is a presenting feature as described in some reported cases in children. Hemoptysis could be the only symptom of DAPVF in adults. This case highlights the importance of imaging in the diagnosis of such rare anomalies.