Background

Amyloidosis is a heterogeneous group of diseases caused by the extracellular deposition of autologous fibrillar proteins, which aggregate into a three-dimensional ß-lamina disposition that impairs normal organ function [1]. The main subtypes of systemic amyloidosis are primary AL amyloidosis (AL), secondary AA amyloidosis (AA) amyloidosis, familial amyloidosis, senile amyloidosis, and ß2-microglobulin-related amyloidosis [2]. AL is the most prevalent subtype in developed countries. Due to its association with inflammatory and infectious diseases, AA is also one of the most reported subtypes [3].

Amyloid deposits in AA are composed mainly of the serum amyloid A (SAA) protein, an apolipoprotein of high-density lipoproteins that serves as a dynamic acute phase reactant [4]. In AL, there is an abnormal folding that results in either a proteolytic event or an amino acid sequence that renders a light chain thermodynamically unstable and prone to self-aggregation [5].

Clinically, any organ tissue can be involved in any type of amyloidosis, which often makes a distinction between them a difficult task. While AA more often presents with renal disease (ranging from subnephrotic proteinuria to overt nephrotic syndrome and end-stage renal disease) in patients with underlying chronic inflammatory conditions, AL more frequently presents with cardiomyopathy, a rare occurrence in the former [6,7]. By the conjugation of both clinical and histological features, it is usually possible to distinguish the two subtypes.

Pulmonary silicosis is an occupational disease caused by silica inhalation. Its pseudotumoral form is very rare. It is known to be associated with pulmonary tuberculosis and lung cancer. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that its physiopathology is based on chronic inflammation, by activation of the inflammasome, triggered by silica crystals [8,9].

Case Presentation

The patient is a 66-year-old Caucasian man with a background of pseudotumoral silicosis and chronic renal disease (Stage b A3, with a creatinine range between 1.8 and 2.0 mg/dl and a TFG 20 ml/minutes/m2). He had a 7-year history of intermittent fever and proteinuria (maximum of 3 g/dl). He was admitted following a 7-day period of diarrhea and fever. On the previous weeks, he had severe asthenia and significant weight loss. He was cachectic, febrile (38ºC), with low blood pressure (85/56 mmHg), and no other major findings on physical examination. Macroscopic hematuria was detected. Blood tests showed mild normocytic anemia (Hb 10.6 g/dl), C-reactive protein of 45 mg/l, mild leukocytosis (12,000 cells per mm3) with neutrophilia (7,000 per mm3), and creatinine 4.5 mg/dl. Platelet levels were normal, and no liver changes were found. The abdominal and thorax image showed no acute changes.

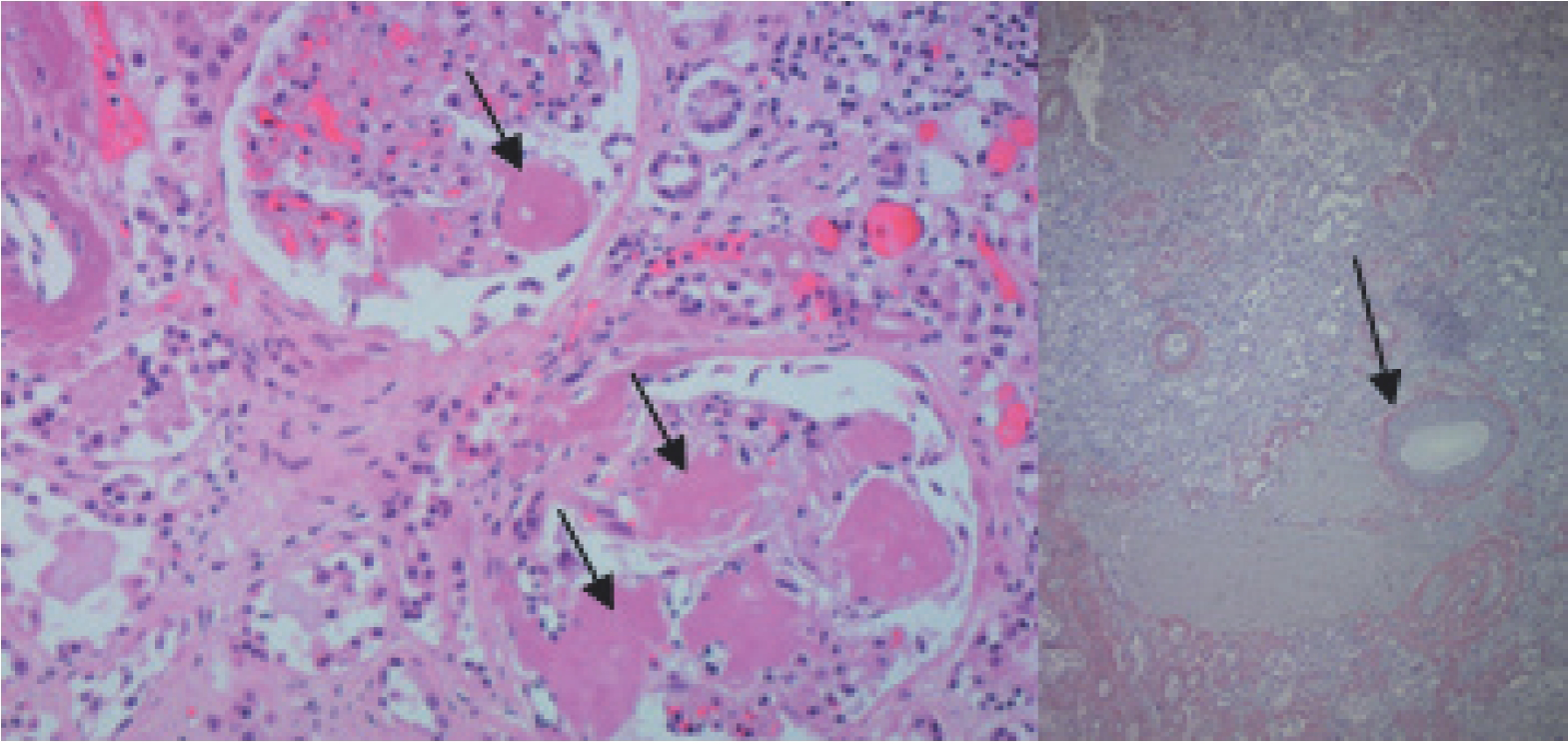

In the presumption of sepsis, empirical antibiotics and fluids were initiated, but symptoms persisted despite 7 days of treatment. Blood and urinary cultures were negative. Due to persistent hematuria and diarrhea, vesical and rectal biopsies were obtained, revealing the presence of amyloid. The patient became anuric and started hemodialysis. For this reason, a urinary immunoelectrophoresis could not be obtained. Because of the multisystemic impairment, such as hypotension, diarrhea, hematuria, and functional deterioration, other biopsies were performed (skin, thyroid, and salivary gland), and they were all positive for amyloid (Figures 1–4). Electromyography confirmed motor-sensitive polyneuropathy. The whole picture was attributable to systemic amyloidosis.

Amyloid deposits on more than 50% of the glommerules (kidney)-right; congo red positivity (kidney)-Left.

An investigation was conducted to identify the subtype of amyloid: rheumatoid factor was slightly positive, and the rest of autoimmunity study is negative (ANCA, anti-endomysium, anti-Scl70, anti-RNA polymerase, and cryoglobulins); monoclonal gamopathy was excluded, as well as familial mediterranean fever (MEFV gene sequentiation), TRAPS syndrome (TNFRSF1A gene sequentiation), Fabry disease (alfa-galactosidade A activity), active and latent tuberculosis, and also lymphoma. The serum amyloid protein A was positive in immunohistochemical analysis, and there was a restriction for lambda chains, suggesting that it might be an AA or AL type. On the other hand, the potassium permanganate test, which is considered positive when the sample loses de “Congo red” staining, favored AA type (also suggested by the positive rheumatoid factor and fever). These tests were performed at different hospitals, and the results were always concordant.

Corticotherapy was initiated with prednisolone in a dose of 1 mg/kg/day, with no clinical response. The patient died. An autopsy was consented by the family. A better characterization of the amyloid was made with immunoelectronic microscopy: amyloid fibrils were intensely and specifically immunoassayed with a monoclonal anti-SAA antibody, whereas anti-kappa and lambda light chains, anti-transthyretin, and anti-apolipoprotein AI antibodies were all negative, excluding AL and confirming AA subtype. All the inflammatory causes that are known to be associated with AA were also excluded.

Discussion

Amyloidosis is a heterogeneous group of diseases. All organs can be affected in AL, except the central nervous system. In the AA subtype, renal and gastrointestinal involvement is common (proteinuria, malabsorption, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, diarrhea, or bleeding); peripheral polyneuropathy and skin involvement are rare [10]. In the patient, the clinical presentation had elements of the two entities. The abrupt evolution observed at the end is not common in any kind of amyloidosis.

All tests performed at the center for identifying the amyloid subtype were inconclusive. Immunohistochemistry tests showed contradictory results. This technique is usually sufficient to determine the fibril protein type in AA amyloid, as there are excellent commercially available antibodies, but tandem mass spectrometry can be useful in nondiagnostic or un-interpretable cases. The samples were sent to an international center, and immunoelectron microscopy was performed, revealing the AA subtype.

We have excluded all the conditions usually associated with AA; no infectious, autoimmune, or inflammatory disorder was found. We excluded the most common genetic conditions and no clinical or physical signs suggested other genetic disorders. The only disease that could be presumed to be associated with AA was the pseudotumoral silicosis. The patient presented with mild leukocytosis with neutrophilia (documented 4 years before admission) possibly traducing a chronic inflammatory state. Despite common, no thrombocytosis was found [11]. Reviewing the international literature for similar cases, we found an anecdotal report described in 1932 and a case presented in a Spanish meeting of Nephology, but no association with the pseudotumoral form of silicosis [12].

Recent studies suggest the association between silica exposure and autoinflammatory diseases [13,14]. Silicosis is characterized by chronic inflammation in the upper lobes of the lungs. The ingestion of silica particles by alveolar macrophages initiates an inflammatory response. Silica exposure, per se, is associated with rheumatoid factor positivity. Pseudotumoral silicosis is known to be associated with chronic inflammation [15]. We hypothesize that this inflammatory state could be the feature associating with silica exposure and amyloidosis. It has been suggested that silica induces inflammasome activation leading to the maturation and release of proinflammatory cytokines. NLRP3 is the most studied inflammasome, leading to the release of interleukins 1 and 18. This mechanism justifies the association between silicosis and inflammation [9]. There is a speculation that this mechanism is also associated with triggering autoimmune diseases, and we suppose that this could also represent the trigger to an AA.

Conclusion

At the time of this publication and to the best of authors’ knowledge, AA has never been described to be associated with pseudotumoral form of pulmonary silicosis. We believe that an inflammatory response associated with pulmonary silicosis was the trigger to the development of AA.

Amyloidosis is a common condition among elder patients.

There are many subtypes of systemic amyloidosis: AL, AA, familial, senile, and ß2-microglobulin-related amyloidosis.

AL is a consequence of a plasma cell disorder characterized by amyloid deposits of immunoglobulin light chains

AA is associated with inflammatory diseases.

There are no specific symptoms of amyloidosis but impaired renal function and anemia are common.

The authors present a disease association of AA that has never been described (pulmonary silicosis).