Background

Horseshoe kidney occurs in 0.25% of the whole population worldwide [1]. Most common cancer seen in horseshoe kidney is adenocarcinoma which accounts for almost 50% of tumor followed by Wilms’ tumor and then upper tract urothelial cell carcinoma (UTUC). Older terminology of urothelial carcinoma is transitional cell carcinoma. The incidence of UTUC is less than 5/100,000 and among them renal pelvic urothelial carcinoma is in 0.0025% or 2.1 cases/10,000,000. The incidence of renal pelvic urothelial carcinoma is three to four times higher in a horseshoe kidney as compared to the normal population [2]. The gold standard of treatment for UTUC is complete nephroureterectomy with removal of a cuff of urinary bladder. Due to multiple vascular anomalies associated with horse shoe kidney, high expertise is required for surgical intervention. UTUC has increased risk of local recurrence even after complete surgery. Here, we will discuss a case report and adjuvant treatment options.

Case Presentation

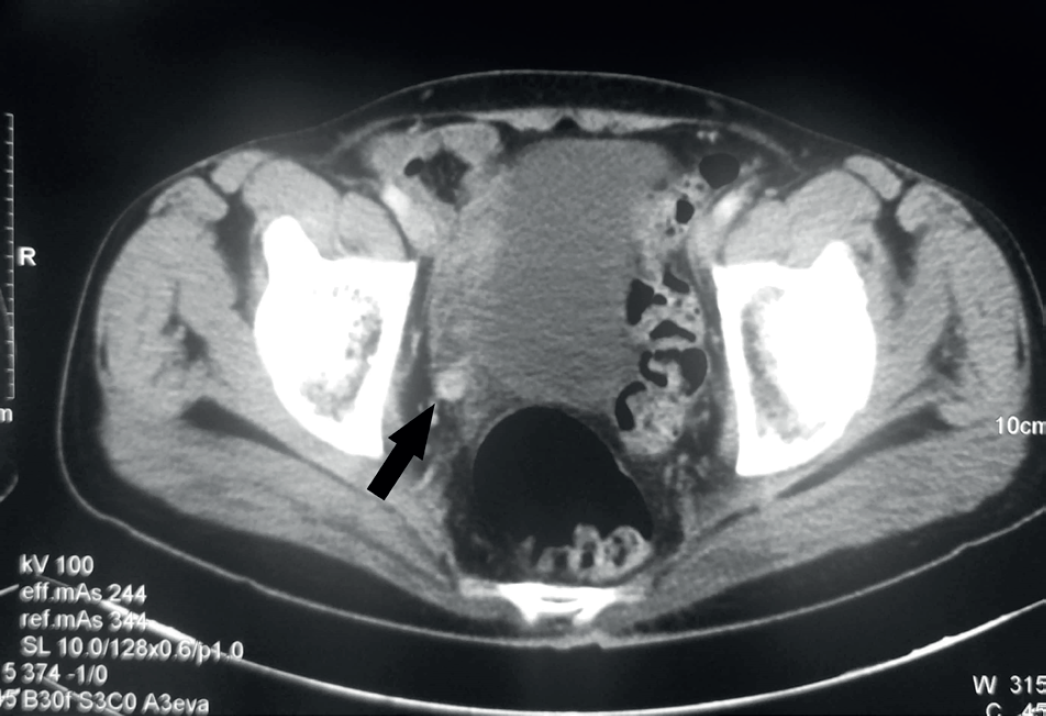

A 60-year-old male, known chronic smoker presented with the complaint of painless gross hematuria for the past 2 months. The general built of the patient was good with eastern cooperative oncology group performance score of 1. Imaging with USG KUB was grossly suggestive of right renal mass. Contrast enhanced CT (CECT) scan of the abdomen revealed a right sided horse shoe shaped kidney with mild hydronephrosis. A heterogeneously enhancing mass sized 37 × 55 mm in upper pole of right kidney was seen with no significant lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging findings was suggestive of a right renal pelvic mass of size 40.7 × 35.5 mm with heterogeneously enhancement (Figure 2 and 3). The diagnosis was assumed to be renal cell carcinoma and the patient was planned for nephron sparing surgery. On excision around 50 × 30 mm sized mass was seen arising from right renal pelvis intra operatively. Frozen section had revealed urothelial carcinoma. Following which complete right sided nephrectomy was done and ureteric stump was left. Post-operative period was uneventful. Histopathology confirmed as low-grade urothelial carcinoma, non-muscle invasive type. Patient was kept on follow up. At first follow up after 3 months cystoscopy findings were normal. CECT abdomen done after 10 months was suggestive of poorly excreting residual right moiety with right side ureteronephrosis with dilated mid-lower right ureter with eccentric mural thickening with enhancement (Figure 4). Cystoscopy revealed 40 × 50 mm solid appearing growth at right ureteric orifice with severe trabeculations. Patient underwent trans urethral resection of bladder tumor with open uretectomy and bladder cuff excision. A total of 10 cm of ureter filled with solid growth along the whole length and reaching up to the bladder cuff was excised. Histopathology was reported as low-grade urothelial carcinoma not invading lamina propria.

Discussion

Very few case reports have been published showing urothelial carcinoma in horse shoe kidney [3–7]. The incidence of renal pelvic urothelial carcinoma in a horseshoe kidney is more than the normal kidney mainly due to chronic obstruction. High likelihood of renal stone and infection causes chronic irritation and inflammation which ultimately leads to the development of malignancy. Mainstay of treatment in carcinoma kidney is complete surgical excision. Surgical intervention in the case of horseshoe kidney is dangerous, as the frequency of anomalous vascular supply of the horseshoe kidney is high and the isthmus consists of parenchyma. Because of anomalous vascular supply, it becomes difficult to identify and dissect multiple renal arteries and veins. That is why laparoscopic surgery is seldom preferred. Patients with resected locally advanced (T3, T4N0, N+) stage have a high risk of relapse and death from disease despite adjuvant treatment. Relapse can occur as local failure or distant metastasis. Partial nephroureterectomy were more likely to have local relapse (46%) as compared to those who underwent complete nephroureterectomy (15%) [8]. Most common local recurrence site is urinary bladder, about 22%–47% [8].

CECT abdomen images during recurrence showing dilated tortuous distal ureter with intaluminal soft tissue and asymmetrical urothelial thickening.

UTUC is multifocal which is supported by two theories. First hypothesis is field cancerization where whole urothelium of genitourinary tract is exposed to the same urinary carcinogens. In this process, multiple carcinogenic alterations occur in the cell lining of the entire urothelial tract which leads to the malignant transformation of urothelial cells in multiple niches. Second hypothesis suggests intraepithelial migration. It explains the formation of genetically altered clonal cells from a carcinogenic insult caused to a single group of cells. These cells further spread throughout genitourinary tract via intraepithelial migration, cell shredding, and reimplantation. These events lead to multiple synchronous and metachronous tumors in the genitourinary tract. Even after complete surgical excision the risk of recurrence remains, and therefore, defines the rationale for adjuvant treatment. No clinical trials have been conducted for the role of adjuvant treatment in T1 low-grade tumors. Adjuvant chemotherapy has been tried in some parts of the world for locally advanced UTUC. In a study by Kwak et al. used methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin and cisplatin (MVAC) regimen in tumors of AJCC staging >T2. The recurrence was less in patients undergoing chemotherapy as compared to those who did not (37.5% vs. 63.6%), which was not significant (p = 0.17). However, overall survival significantly improved in with the use of chemotherapy (p = 0.006). Lee et al. also used MVAC regimen in T3 UTUC and found no improvement in recurrence free survival with the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Hellenthal et al. did a multi-institutional study to see the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in high risk UTUC, i.e., pT3/pT4 or lymph node positive. They also did not find any significant survival benefit with use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Soga et al. also found out that use of adjuvant chemotherapy significantly decreases bladder recurrences but has no impact on overall survival. Chemotherapy has also been tried in neoadjuvant setting. The theoretical advantages of neoadjuvant chemotherapy include subclinical metastatic disease eradication, reduction of tumor bulk, improved patient tolerability prior to surgical extirpation, and the ability to deliver higher chemotherapy doses (due to the loss of renal function that occurs with nephroureterectomy). Igawa et al. found a good pathological response with use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Audenet et al. based on their review advised individualized use of chemotherapy by keeping in mind renal function, stage, performance status. Platinum-based chemotherapy regimen (MVAC/Gemcitabine-cisplatin) is often proposed in metastatic or locally advanced disease but all patients cannot tolerate chemotherapy due to comorbidities and impaired renal function after radical surgery. Newer studies have included limited numbers of patients and have shown poor patient outcomes after both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. Even EUA guidelines [9] are based on expert opinion rather than evidence-based data. Option of radiation therapy has also been tried as adjuvant treatment post-surgery. Local control improved in patients with high grade or advance stage tumor, tumor with close margins, or positive nodes [10,11]. A randomized trial by Chen et al. has suggested a survival benefit with use of adjuvant RT in T3/T4 tumors. Use of intravesical Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) instillation has shown to reduce bladder recurrences [12]. Despite of the given studies, not enough evidence has been generated to define the role of adjuvant RT or chemo RT [13–15]. In our case, patient did not underwent standard complete surgical excision, which led to local recurrence and it was completed only after recurrence. Based on review of literature, patient was given intravesical BCG for 1 year post complete surgical excision. At present, patient is doing fine and has no recurrence since past 2 years.

Conclusion

Urothelial carcinoma of renal pelvis in horse shoe kidney is a rare entity, but more often seen vis-à-vis normal kidney. Radical nephroureterectomy with removal of a cuff of urinary bladder remains the standard of treatment. But often, locoregional recurrences are seen post-surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy has been tried by various authors and it did not show any clear benefit. Even in neoadjuvant setting chemotherapy role is not clearly established, preliminary evidences suggest a survival benefit. Adjuvant radiotherapy in high risk renal pelvic urothelial cell cancer has shown to be beneficial. Post-operative intravesical therapy has been shown to decrease the bladder cancer recurrence rates. Judicious selection of adjuvant treatment on individualized basis may improve locoregional control.

What is new?

Urothelial carcinoma of renal pelvis in horse shoe kidney is a rare entity, with very few case reports in the literature. Radical nephroureterectomy with removal of a cuff of urinary bladder is the standard of treatment. Despite of complete surgery, there are locoregional recurrences and adjuvant treatment option not discussed anywhere. Here we will be discussing about pattern of recurrences in incomplete surgery and adjuvant treatment options.