Background

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common and potentially life-threatening medical emergency with an incidence of 103-172/100,000/year [1]. Due to advances in endoscopic hemostasis and the development of H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors, the number of patients receiving surgical treatment for UGIB has notably decreased in the recent decades [2]. Nowadays, only 2.6% of the patients need additional surgical or angiographic intervention after unsuccessful endoscopic hemostasis [3]. Consequently, the uncontrolled UGIB results as an interdisciplinary challenge for endoscopists, surgeons, radiologists, and intensive care physicians, especially regarding an extraordinary rare origin of hemorrhage as presented in the following case report.

Case Presentation

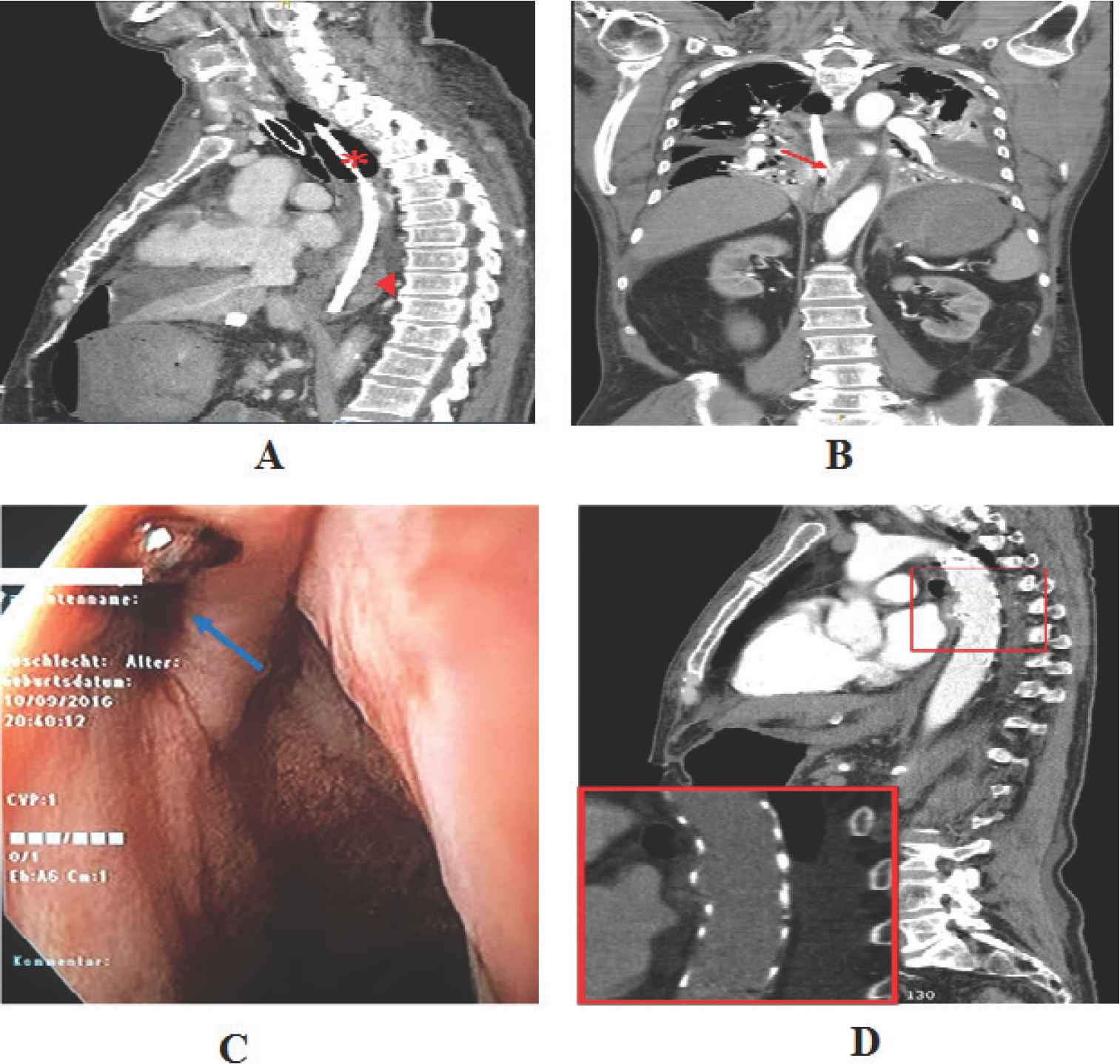

A 72-year-old man was admitted to a community hospital with a course of syncope, melaena, and hypotension. Already during the preparation for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), projectile vomiting of fresh red blood occurred. In the course of the initial EGD, massive arterial bleeding was detected under the assumption of a gastric ulcer as the source of the hemorrhage. Despite extensive endoscopy, no distinct origin of bleeding could be identified due to large gastric clots. Therefore, gastrostomy was performed. There were only a few mucosal defects and atypical fundus resection was conducted. After short stabilization, the patient showed hemorrhage from mouth and nose. On suspicion of iatrogenic lesion of upper GI, EGD was resumed and showed a heavy arterial bleeding of the esophageal wall. In the following hours, attempts of endoscopic hemostasis with clipping and esophageal stenting failed and a sengstaken tube was placed. During these procedures, which lasted for 12 hours, 55 units of packed red blood cells, 39 units of fresh frozen plasma, 4 units of platelet concentrates, and 4,000 IU of prothrombin complex concentrate were administrated. As all possibilities were exhausted, the patient was transferred from the community hospital to the resuscitation area of our clinic via rescue helicopter. An immediately conducted computed tomography of the thorax and abdomen showed a penetrating aortic ulcer (PAU) of the descending aorta as well as distension of the stomach by large amounts of clotted blood, including the formerly placed esophageal stent. As results of an abdominal compartment syndrome, an elevated ventilation pressure along with a reduced cardiac output called for a prompt transfer to the OR for abdominal decompression laparotomy. Directly after laparotomy, spontaneous rupture of the gastric suture line occurred. Huge amounts of clotted blood and the lost stent were evacuated. Pulsatile blood flow came out of the esophagus despite the sengstaken tube; however, bleeding could be contained by placing a clamp on the distal esophagus. Meanwhile, definite evaluation of CT revealed the penetration of the esophagus by PAU, resulting in an aortoesophageal fistula (Figure 1A and B). After preparation of the left femoral artery, we managed to occlude the fistula by implantation of an aortic stent graft [Medtronic Valiant® Captivia® TEVAR (thoracic endovascular aortic repair) Stent Graft] in the descending aorta under image converter control, resulting in immediate cessation of the bleeding. Intraoperative EGD confirmed bleeding arrest and integrity of the esophageal wall except for a small ostium at 21 cm from the upper incisors (Figure 1C). After reconstruction of the stomach and closure of the abdomen the patient was then transferred to the ICU. Computed tomography scan on the first postoperative day showed a correct stent position and a complete occlusion of the aortoesophageal fistula (Figure 1D). In the further postoperative course, the patient showed quick recovery in the ICU and could be discharged to a rehabilitation clinic on the 18th postoperative day.

(A) Sagittal CT shows correct position of sengstaken tube (*) and contrast material accumulation in the lower esophagus (►). (B) Coronal plane shows extravasation of contrast material from the PAU thoracic aorta to the esophagus, i.e., an aortoesophageal fistula (red arrow). (C) Intraoperative endoscopy reveals a small ostium of the esophageal wall with an adherent blood clot (blue arrow). (D) Sagittal picture on the first postoperative day confirms correct stent graft position with full covering of the former PAU (red square).

Discussion and Conclusion

Primary aortoenteric fistulas (PAF) are uncommon clinical conditions which show a mortality of 100%, if untreated [4]. While secondary aortoenteric fistulas can be observed in 0.5%-2% of patients after aortic reconstruction repair, resulting from periprosthetic infects, the PAF is an extreme rare pathology with a yearly incidence of 0.007/million [5]. In a meta-analysis by Saers and Scheltinga, most of the PAF-cases were associated with an aortic aneurysm. Foreign bodies, tumors, radiation therapy, and infections were further reasons of fistulas. The PAF affected most frequently the duodenum (42%), followed by the esophagus (28%) [6]. However, our patient neither had an aortic aneurysm nor a history of cancer or radiotherapy. Furthermore, the initial blood cultures and serology for fungal infections revealed no infectious cause for PAU and mesaortitis luetica was ruled out by TPHA test. Albeit PAF is an extreme utmost cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, the described case teaches two important lessons. In the first place, endoscopy should not be exhausted to the disadvantage of a timely surgical intervention. Secondly, early CT angiography should be performed in any case of gastrointestinal hemorrhage with unlocated site of bleeding. Above all, a multidisciplinary approach to massive GI bleeding is recommended in all cases.