Background

Post-traumatic pseudolipomas (PTLs) are a poorly recognized and investigated clinical entity and were first documented in the literature in 1932 [1]. Adair et al defined pseudolipomas as normal adipose tissue that accumulates in abnormal locations. The relationship between traumatic events and development of these benign adipose tumors was also suggested. Unlike lipomas, PTLs have a strong female predominance (12:1), often localized in the lower extremity, and in the trochanteric and gluteal regions [2]. These tumors are benign and apart from cosmetic implications, have no true clinical significance. They can be a source of anxiety to patients and may present a diagnostic dilemma to physicians, especially with atypical presentations of this already uncommon entity. The purpose of this report is to describe one such unusual presentation in the form of a 31 year old male professional surfer. After review of existing literature and to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case of PTLs to be reported with this presentation

Case presentation

A 31 year old male presented with an open calcaneal fracture for orthopedic intervention after an accident that occurred during an off-road four wheeling race. He had a past medical history of alcoholism and gastric ulceration. He did not have any fixed profession but stated himself to be a professional surfer. Incidentally, he was noted to have swellings of his upper abdomen on either side of the

Right lateral supine view of symmetrical ventral post-traumatic pseudolipomas (knees partly flexed)

midline. The patient believed this to be fluid collections owing to repetitive surfboard trauma. He recalled significant purpuric bruising that occurred approximately four years prior during a surfing competition. Since then he had persistent painless swelling of his upper abdomen (see Figures 1 and 2). The patient noted that the swellings progressively increased over the years. He did not have any similar swellings elsewhere on his body.

An Internist was consulted to evaluate the etiology of these swellings. On examination, the masses were soft and exhibited the “slippage sign”, elicited by gently sliding fingers along the edge of the tumor. The tumor was felt to slip out from under, as opposed to a sebaceous cyst or an abscess that is tethered by surrounding induration. There was no fluid thrill or transillumination elicited. The overlying skin was non-erythematous and normothermic. No secretions were elicited on palpation and there was no punctum present. No supernumerary nipples were present. Serum Prolactin and routine chemistries were within normal limits. The diagnosis of PTLs was made

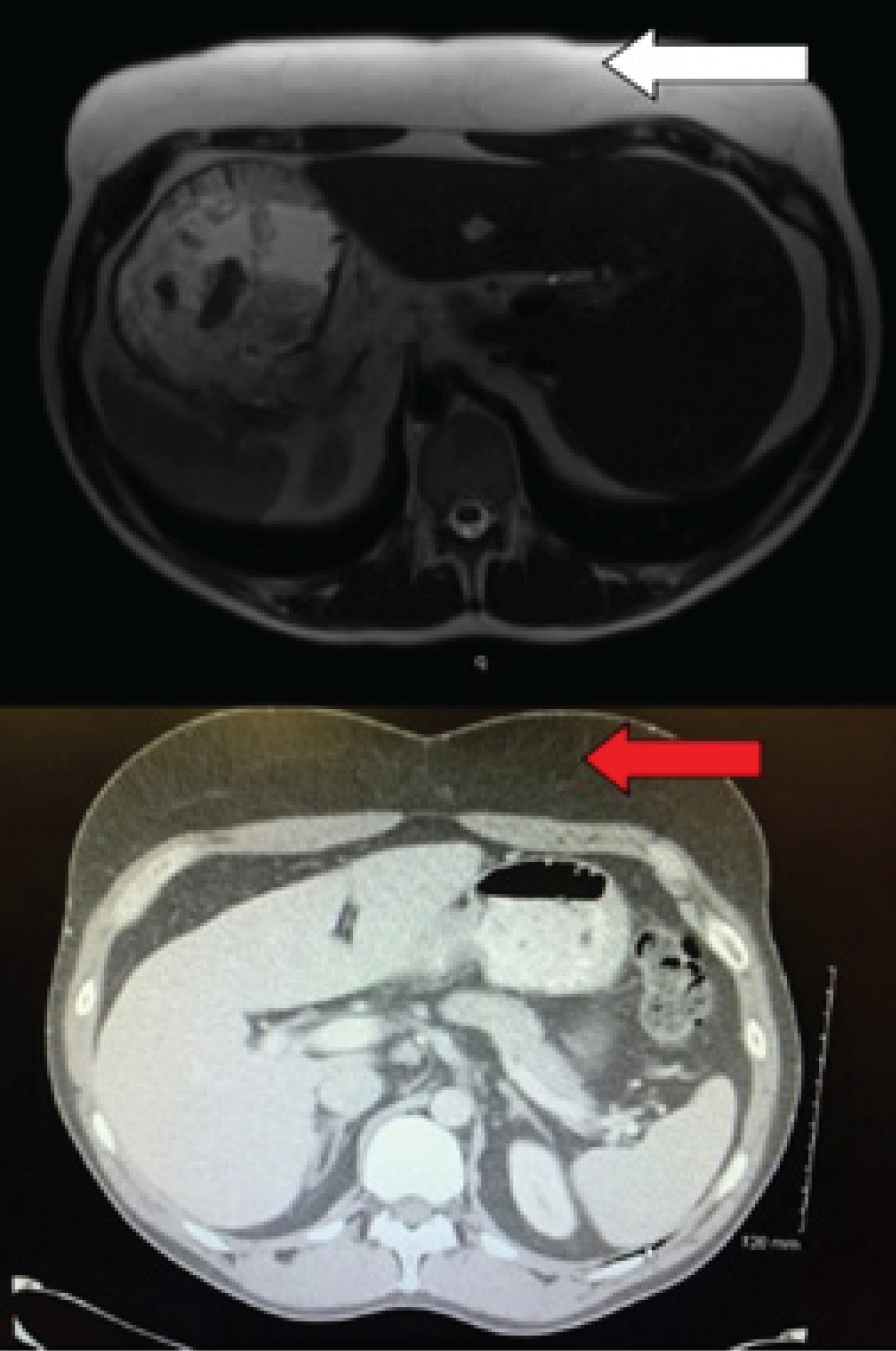

Plain T2W MRI axial image of abdomen demonstrating increased prominence of the subcutaneous fat in the form of hyperintensity (white horizontal arrow). There was no evidence of a focal encapsulated lesion or fluid collection. (b) CECT axial section of abdomen shows well defined increased soft tissue of fat density on the frontal aspect (horizontal red arrow).

via Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which revealed homogeneous, unencapsulated adipose tissue within the upper abdominal wall that did not enhance with Gadolinium (see Figure 3). The patient declined surgical intervention since he was asymptomatic and there was no indication of an underlying malignant tumor.

Discussion

Lipomas are benign tumors of adipose tissue and have been found in almost all systemic adipose tissue sites. The term ‘pseudolipoma’ has been coined to discriminate this trauma-induced entity from ‘true’ lipomas which are idiopathic and without a preceding history of trauma. PTLs were first reported by Adair et al in 1932 [1] but trauma as etiologic factor was formally proposed by Meggitt and Wilson in 1972 [3]. In their description of the “battered buttock syndrome”, female patients were found to develop lipomas in the setting of preceding acute trauma. They postulated that when excessive force is applied locally to adipose tissue it may cause fat compartments to fracture, shearing off the anchoring between the skin and deep fascia. This leads to protrusion of adipose tissue, manifesting as PTL after the bruising and hematoma resolve.

However, several authors have not been able to identify anatomical confirmation for the hypothesis of deep fascial injury leading to the development of PTL [2,4]. In this case presentation, the patient was not obese and the development of de novo adipose tissue in the ventral lower thorax/upper abdominal region favors the theories postulated by Galea et al in 2009 [5]. In their review, they noted recent work with Zymosan-A (ZA) induced neo-adipogenesis (an inflammagen derived from an insoluble

polysaccharide component of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall). When this inflammagen was added to a vascularized tissue engineering chamber, a systemic inflammatory response mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 ZA induced significant adipogenesis in an inverse dose-dependent manner (P<0.001) [6].

Regardless of a mechanical or inflammatory etiology, PTLs have a low incidence and their formation is largely unpredictable. Prior reports have described occupational or hobby-based trauma as precipitants. Noteworthy is the tradition of “tar barreling” native to Ottery St. Mary, Devon, Southwest England. In a tradition dating back to the 17th century, barrels soaked in tar are set ablaze and carried on the back between the shoulders though the streets. The development of the “tar barreler’s hump” has been documented in the literature as a manifestation of the acute trauma associated with this tradition [7]. These are essentially PTLs developing at posterior aspect of the neck, known to occur anecdotally in a few of the generations of tar barrelers from this township. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior published data exists on the development of PTL in association with professional or recreational ocean surfing.

Despite the lack of histological analysis in this case, since the patient declined surgical intervention, MRI findings were consistent with PTL as documented by Theuman et al in 2005 [8]. On MRI examinations, PTLs appear as thickening of the subcutaneous fat in the sites of injury rather than a distinct mass. The entire lesion has signal intensity identical to subcutaneous fat for all pulse sequences. No discernible enhancement is noted on Gadolinium enhancement and PTLs are not confined within a capsule. In a case series by Theumann et al, each of the ten patients noted antecedent visible hematoma at the site of trauma prior to PTL formation. This is also consistent with the history obtained from the surfer. Malignant transformation of PTL into liposarcoma has not been described in the literature. The recommended treatment for PTL is liposuction but surgical excision may be explored depending on location, size and the severity of any associated symptoms [9].

Conclusion

PTLs are a distinct clinicopathological entity but, owing to unpredictable presentations, are poorly recognized by physicians and surgeons alike. This case demonstrated a previously unpublished association of PTL with surfboard trauma with a goal to raise awareness. Inclusion of PTL in the differential of a lipomatous lesion can be achieved by eliciting a prior history of trauma. PTLs have not been documented to undergo malignant transformation and patient anxiety may be allayed with the diagnosis. Liposuction or surgical excision may be offered for cosmetic reasons or if symptoms arise.