Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak started in the Chinese City of Wuhan, Hubei province, in December 2019, with a cluster of patients diagnosed with a new unknown viral pneumonia.(1) The novel beta coronavirus, initially named 2019 n-CoV, was later renamed SARS-CoV-2.(2) The WHO subsequently declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 12, 2020. By mid-January 2022, 3.5 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and about 100,000 deaths had been recorded in South Africa.(3) The actual figures were probably higher due to the limited testing capacity and deficient data collection methods in the initial phases of the pandemic.

Transmission of COVID-19 is primarily via respiratory droplets, with an incubation period of less than 2 weeks, characterised by high viral loads in the early stage of the disease.(4,5) SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause five different outcomes: asymptomatically infected persons (1.2%); mild to medium cases (80.9%); severe cases (13.8%); critical cases (4.7%); and death (2.3%).(6,7) The most common symptoms at admission are fever, cough, and fatigue. Less frequent symptoms include myalgia, shortness of breath, headache, diarrhoea, and sore throat.(8–10). The Omicron-dominated wave reduced the disease severity and admission rates, with an associated increase in the asymptomatic rate.(11,12) Asymptomatic carriage rates in patients presenting for vaccination in the Omicron period were 27%, compared to pre-Omicron rates of 1%–2.4%.(13) Vaccinated individuals are also much less likely to require hospitalisation, ICU care, chronic complications, or death.(14)

Imaging by CT is highly sensitive in identifying the features and complications of COVID-19, with a sensitivity of up to 97% and a specificity of 56%.(4) Imaging by CT is also associated with over 90% positivity rate; initial findings include bilateral, multilobar ground glass opacities, with predominantly posterior and peripheral distribution.(15) Less common patterns include superimposed consolidation, septal thickening, bronchiectasis, pleural thickening, and subpleural involvement, especially in the later stages of the disease.(10,15)

Multiple studies have reported hypercoagulability in patients with COVID-19.(16–18) Anticoagulation has also been shown to be associated with decreased mortality in severe COVID-19 patients with coagulopathy.(17,19) The prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism in various studies ranged between 23% and 30%.(20,21)

Most previous studies focused on various temporal points within the pandemic, but none adequately compared the findings associated with the multiple waves of the pandemic. This study aimed to describe the common findings on CT chest and CT pulmonary angiograms in COVID-19 patients and assess whether these findings differed between the Beta, Delta, and the Omicron variant phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

The study was a retrospective review of CT chest and CTPA studies at 3 Academic hospitals affiliated with the University of Witwatersrand: Helen Joseph Hospital, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, and Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital. The study period was within the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic from October 2020 to February 2022. Data was accessed from the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) and physical hospital records using the search parameter COVID-19. The study population included patients over the age of 18 years with COVID-19 undergoing chest CT or CTPA. These patients had confirmed RT PCR or rapid COVID-19 positive results. Patients with incomplete documentation and technically inadequate scan images were excluded from the study sample. Patients with significant pulmonary comorbidities, such as metastatic disease or pulmonary tuberculosis, were also excluded.

Demographic and imaging data collected included age, sex, presence of pulmonary embolism, and other CT findings such as ground glass opacities, distribution, consolidation, pleural effusions, fibrotic banding, and bronchiectasis. The timing of the scan from the positive test was also recorded.

Findings were grouped according to a predetermined range of CT findings and assessments in the CT reports and included the presence of pulmonary embolus and its location in the pulmonary arterial tree, ground glass opacities, crazy paving, pleural effusions, bilateral involvement, posterior distribution, multilobar involvement, peripheral distribution, and consolidation. The date of the study was recorded to enable placement within the specific infection period and, therefore, a particular virus strain before analysis. The various findings were compared among the different virus subvariants, divided according to data monitored by the Network for Genomic sequencing:

CT technique

The chest CT protocol at the three hospitals is similar. CT machines used for imaging included the Siemens128-slice, Philips Brilliance 64-slice, and Toshiba 128-slice Prime Aquilion CT scanners. Patients are scanned supine with the breath-hold technique to reduce respiratory motion artifact. For CTPA studies, a region of interest is drawn on the main pulmonary artery, and bolus IV injection of non-ionic contrast medium (Omnipaque 300) 100ml is given at a rate of 3-5ml/s. Images were reconstructed to 0.5mm to 1mm slice thickness in soft tissue, mediastinal, and lung windows.(20)

Data management

Data was entered into an Excel sheet from the data collection sheets. A de-identified Excel spreadsheet was imported into the STATA software version 15 for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentages. Continuous data was presented as mean/median with standard deviation if normally distributed and interquartile range if skewed. Missing information was checked on each variable. A statistically significant association was set at P-value <0.05. All statistical test analyses were two-sided, and p values <0.05 were statistically significant.

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Witwatersrand granted ethical approval for the current study.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 307 COVID-19-positive patients undergoing chest CT and CTPA imaging. The mean age was 53 15 years, with an age range of 16 to 88. Imaging was performed within a median of 17 days (IQR 12-30) after a positive COVID-19 result. Females, 192 (63%), constituted most of the cohort. Most imaging studies performed were CTPA 242 (79%), of which 78/242 (32%) were diagnosed with pulmonary thromboembolic disease. (Table 1).

Overall CT imaging characteristics of the reviewed records

| Imaging feature | Total n (%) | Beta n (%) | Delta n (%) | Omicron n (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Female Male | 192(63) 112(37) | 63(57) 47(43) | 92(64) 51(36) | 37(73) 14(27) | 0.165 |

| CT study Chest CTPA HRCT | 16(5) 242(79) 49(16) | 8(7) 81(72) 23(21) | 6(4) 124(86) 14(10) | 2(4) 37(73) 12(23) | 0.042 |

| Ground Glass Opacities | 236(77) | 91(81) | 112(78) | 33(65) | 0.071 |

| CT Chest Distribution | |||||

| Diffuse | 68(22) | 21(19) | 42(29) | 5(10) | 0.009 |

| Patchy | 181(59) | 71(63) | 78(54) | 32(63) | 0.422 |

| Peripheral | 180(59) | 77(69) | 75(52) | 28(55) | 0.023 |

| Septal thickening | 179(58) | 67(60) | 95(66) | 17(33) | <0.001 |

| Consolidation | 89(29) | 24(21) | 51(35) | 14(27) | 0.048 |

| Crazy paving | 40(13) | 19(17) | 18(13) | 3(6) | 0.145 |

| Pleural effusion | 45(15) | 16(14) | 21(15) | 8(16) | 0.972 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 48(16) | 16(14) | 25(17) | 7(14) | 0.733 |

| Fibrotic banding | 177(58) | 60(54) | 87(60) | 30(59) | 0.537 |

| Bronchiectasis | 124(40) | 46(41) | 57(40) | 21(41) | 0.964 |

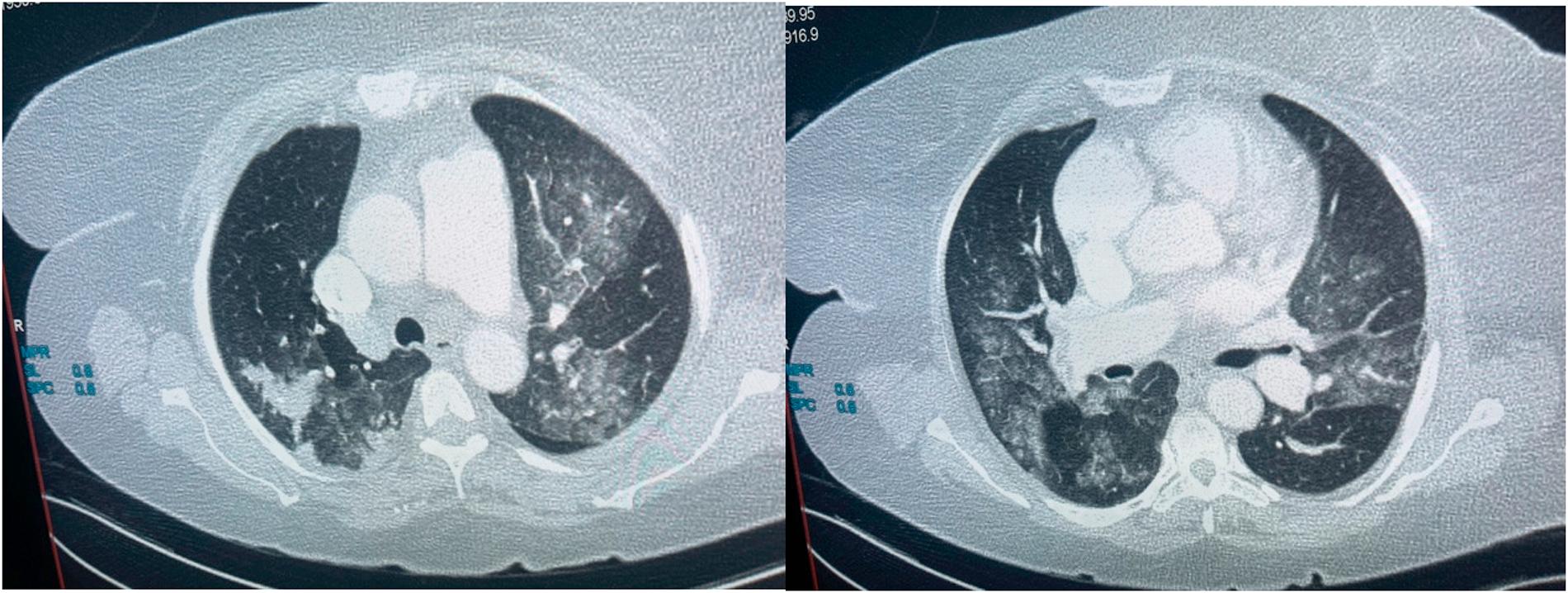

The imaging features were ground glass opacities (77%), septal thickening (58%), fibrosis (58%), and bronchiectasis (40%), followed by the less common findings of consolidation (29%), lymphadenopathy (16%), pleural effusion (15%) and crazy paving (13%). The disease distribution was mainly patchy (59%) and peripheral (59%), with diffuse distribution in 22%. Only septal thickening showed statistical significance when comparing the three waves, with a p-value <0.01. These CT chest imaging findings are depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

Axial images in a patient diagnosed with COVID–19 showing bilateral ground glass opacities, right upper lobe apical–posterior segment patchy consolidation.

An axial CT image in a lung window demonstrating bi–basal bronchiectasis and ground glass opacities with interlobular septal thickening (crazy paving) was imaged 21 days after a positive test.

Findings on chest CT scans were assessed according to infection time course, with periods classified according to the number of days from a positive COVID PCR test; these findings are displayed in Table 2. Fibrotic banding (73%) and bronchiectasis (47%) are comparatively more prevalent when imaging is performed later in the disease course.

Imaging features stratified according to infection time frame from positive COVID-19 test result

| Imaging Feature | <10 days | 10-19 days | 20-29 days | 30+ days | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGO | 31(79) | 70(84) | 34(81) | 42(70) | 0.231 |

| Distribution | |||||

| Peripheral Patchy Diffuse | 19(49) 24(62) 11(28) | 59(71) 57(69) 16(19) | 21(50) 21(50) 14(33) | 37(62) 36(60) 10(17) | 0.043*

0.240 0.160 |

| Interlobular septal thickening | 23(59) | 53(64) | 27(64) | 34(57) | 0.798 |

| Crazy paving | 11(28) | 14(17) | 5(12) | 2(3) | 0.005* |

| Consolidation | 20(51) | 32(39) | 8(19) | 12(20) | 0.001* |

| Pleural effusion | 6(15) | 12(14) | 3(7) | 7(12) | 0.637 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 10(26) | 10(12) | 8(19) | 12(20) | 0.290 |

| Fibrotic banding | 9(23) | 42(51) | 34(81) | 44(73) | <0.0001* |

| Bronchiectasis | 8(21) | 34(41) | 23(55) | 28(47) | 0.013* |

indicates p-values <0.05 which were considered statistically significant

The diagnosis of PTED was solely made on CTPA. The prevalence of PTED was noted to be highest in the delta wave (36%), compared to the beta wave (30%) and the Omicron wave (24%). The overall PTED prevalence was 32% (Table 3).

Analysis of CTPA performed and Positivity Rate

| WAVE | CTPA TOTAL | PTED | |

|---|---|---|---|

| YES | NO | ||

| Beta | 81 | 24 (30%) | 57 (70%) |

| Delta | 124 | 45 (36%) | 79 (64%) |

| Omicron | 37 | 9 (24%) | 28 (76%) |

| Total | 242 | 78 (32%) | 164 (68%) |

| P-Value | 0.081 | ||

Analysis of a subset of 224 CTPAs where the date of COVID diagnosis was available and where the date of the test was specified revealed that most CTPA studies (83; 37%) were performed at 10-19 days post a positive COVID diagnosis, with a positivity rate of 39% (Table 4).

Discussion

This study shows that the most typical CT chest imaging finding is ground glass opacities in a peripheral, patchy distribution. These findings are in concert with multiple previous studies.(4,10)

There were fewer patients with COVID-19 in the Omicron wave, possibly due to a less severe disease pattern than the previous variants. Another study confirmed this finding, which showed that COVID-19 infection with the Omicron variant has a much more indolent disease pattern and low complication rate than previous variants.(12) Another possible explanation for the lower overall number of complications during the Omicron wave is that more of the population had been previously exposed to the virus in the previous waves and, therefore, had increased immunity against severe disease. Also, at the time of infection during the Omicron wave, vaccination had covered a significant proportion of the population, which may have protected more patients against severe illness.(11,14)

Our CT imaging findings demonstrated that particular imaging findings are related to the time course of the infection. However, ground glass opacities remain the predominant imaging finding across the time frames. There is concurrence with Bernheim et al., who demonstrated that early in the infection, there is a predominance of ground glass opacification, with features such as crazy paving consolidation. In contrast, fibrotic banding and bronchiectasis become more prominent when imaging is performed later in the disease course.(15)

The prevalence of PE in our cohort is similar to several published studies, which reported rates between 23% and 30%.(20,21) Most pulmonary emboli were diagnosed with imaging performed 10–19 days post-COVID-19 diagnosis, in keeping with the natural history and congruent with findings by Grillet et al., who noted that PE was diagnosed at a mean of 12 days post-symptom onset.(20)

Limitations

The study has several limitations. Notably, most patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in our setting typically do not undergo CT chest scans as part of their routine assessment. Indications for CT imaging include worsening symptoms, poor response to interventions, and suspicion of pulmonary embolism or post-COVID fibrosis. Consequently, the study cohort comprises individuals with advanced or complicated disease presentations, potentially skewing the CT findings and thus not ideally representing the broader spectrum of COVID-19 patients. Patients with renal dysfunction as a contraindication to contrast administration may not undergo CT imaging. Therefore, the prevalence of pulmonary embolism may have been underestimated.

The CT imaging features were stratified according to infection time frame from positive COVID-19 test result, which may poorly tally with the time post onset of symptoms. Some patients were only imaged after receiving some form of therapy such as antivirals, steroids, and antimicrobials, which may affect imaging findings, which was not accounted for in this study. The patients with more severe symptoms were also more likely to undergo imaging earlier as urgent cases, with less severe cases only imaged later, which may also affect the imaging findings. The impact of comorbidities was not fully assessed in this study. However, an effort was made only to include patients presenting with COVID-19 as the principal primary condition.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the typical CT imaging pattern for patients with COVID-19 was patchy ground glass opacities, largely peripheral and with interlobar septal thickening. Fibrotic banding and bronchiectasis were frequently noted, mainly when imaging was performed late. We found no differences in the CT imaging patterns during the various phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. A high prevalence of pulmonary embolism was also demonstrated.