INTRODUCTION

Seizures can be defined as the presence of electroencephalographic (EEG) evidence of transient excessive or synchronous abnormal neuronal electrical activity involving all areas (generalized seizure) or just one area (focal seizure) of the brain. Depending on the seizure subtype, patients may manifest with one or more of the following features; loss of consciousness or awareness of the environment, involuntary stiffening and/or jerky movements of a body part or the entire body, urinary incontinence, tongue biting, loss of muscle tone, repetitive movements, starring spells, eye blinking, lip smacking, sensory symptoms such as flashing lights or tingling, postictal confusion and emotional lability.(1,2)

In the developed world, seizures are responsible for 1.2% of all emergency department (ED) attendances with first-episode seizures accounting for approximately a quarter of these cases.(3) A first-onset seizure can be described as the first episode of a focal or generalized seizure in a patient not known to have epilepsy or any other seizure disorders.(4) First-episode seizures are not a diagnosis per se but may be a harbinger of a potentially life-threatening underlying illness.

The underlying aetiology of a first-episode seizure is vast and includes hypo- or hyperglycaemia, electrolyte abnormalities, overdose or withdrawal of prescription and non-prescription drugs, eclampsia, septic shock, renal failure, liver failure and intracranial pathologies such as meningitis, stroke, neurodegenerative disorders, intracranial haemorrhage and other space occupying lesions.(5) Various laboratory tests and neuro-imaging modalities, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), have been recommended for the work-up of a patient with a first-onset seizure.(6) Since conditions such as syncope, psychogenic non-epileptic seizure, stroke, narcolepsy and migraine have been reported to mimic the presentation of seizures, an EEG is also recommended in cases where the diagnosis is in doubt.(7)

South Africa is unique in that there are more people living with HIV than any other country in the world.(8) New-onset seizures have been reported to be more common in the HIV-infected population.(9) In addition, difficulties in accessing healthcare services may result in delays in initiating treatment.(10) Local data and guidelines pertaining to the presentation and management of a first-episode seizure are lacking. The aim of this study was to describe the presentation and management of adult patients presenting to the ED with a first-episode seizure.

METHODS

In this retrospective study, medical records of 60 consecutive patients >18 years who had presented with a first-episode seizure to the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) ED over a 6-month period between November 2016 and May 2017 were reviewed. In addition to the ED register, the neurology ward and medical ward registers were also reviewed to identify patients who may not have been included in the ED register. For the purpose of this study, first-episode seizures were defined as a first episode of a focal or generalized seizure in a patient not known to have epilepsy or any other seizure disorder.(4)

Data was collected from patient records and entered into a data collection sheet by the primary investigator. Any missing or conflicting data entries were resolved after discussion with the treating clinician. Information retrieved from patient files included sex, age group, HIV status, time to ED presentation after the seizure, time to return to baseline neurological function following the seizure, type of seizure, presence of clinical features suggestive of a seizure, presence of clinical features indicative of a focal neurological deficit and aetiology of the seizure. In addition, diagnostic investigations that were performed as well as results of relevant diagnostic investigations such as sodium, calcium, urea, creatinine, glucose, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, lumbar puncture, CT scan and MRI scan were also retrieved. Where necessary, outstanding laboratory and radiology reports were electronically retrieved from the hospital National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) database and the Picture Archiving and Communicating System (PACS) portals, respectively. Subjects who were regarded not to have had a first-episode seizure after careful review by the neurology department were not included in this study.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Means, medians and percentages of collected data are described. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand. Consent was obtained directly from subjects with normal mental function or from relatives of subjects with incomplete return to baseline neurological function. Study reporting conformed with the STROBE statement.(11)

RESULTS

A total of 103 medical records of adult patients with a suspected first-onset seizure were reviewed. Forty-three patients were excluded. Of these, 23 patients did not have a seizure or had a pseudo-seizure, 11 patients had a history of epilepsy and 9 patients were <18 years old. The final sample of 60 subjects comprised 35 (58.3%) males. The median age of subjects was 37.4 years (IQR; 29.3–47.7 years). Age group, HIV status, time to ED presentation, time to return to baseline neurological function, the presence of clinical features suggestive of a seizure, patient disposition and selected biochemical parameters of study subjects are described in Table 1.

Characteristics and presenting features of study subjects

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 18–29 | 15 (25.0) |

| 30–39 | 20 (33.3) |

| 40–49 | 12 (20.0) |

| 50–59 | 9 (15.0) |

| 60–69 | 3 (5.0) |

| >70 | 1 (1.7) |

| HIV status | |

| Positive | 17 (28.3) |

| Negative | 22 (36.7) |

| Unknown | 21 (35.0) |

| Time to ED presentation | |

| <60 min | 13 (21.7) |

| 61–120 min | 1 (1.7) |

| >120 min | 19 (31.6) |

| Not documented | 27 (45.0) |

| Time to return to baseline neurological function | |

| <30 min | 16 (26.7) |

| 30–60 min | 11 (18.3) |

| >60 min | 7 (11.7) |

| Not documented | 26 (43.3) |

| Patient disposition | |

| Admitted | 34 (56.7) |

| Discharged | 26 (43.3) |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | |

| <136 | 25 (43.1) |

| 136–145 | 29 (50.0) |

| >145 | 4 (6.9) |

| Not measured | 2 (0.0) |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | |

| <2.15 | 35 (58.3) |

| 2.15–2.5 | 10 (16.7) |

| >2.5 | 0 (0.0) |

| Not measured | 15 (25.0) |

| Urea (mmol/L) | |

| <2.1 | 5 (8.3) |

| 2.1–7.1 | 41 (68.3) |

| >7.1 | 10 (17.9) |

| Not measured | 4 (6.7) |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | |

| 64–104 | 40 (66.7) |

| >104 | 16 (26.6) |

| Not measured | 4 (6.7) |

| *Blood glucose (mmol/L) | |

| <5.6 | 16 (26.7) |

| 5.6–11.1 | 22 (36.7) |

| >11.1 | 5 (8.3) |

| Not measured | 17 (28.3) |

| White blood cell count (×10 9) | |

| 3.9–12.6 | 44 (73.3) |

| >12.6 | 9 (15.0) |

| Not measured | 7 (11.7) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | |

| <10 | 3 (5.0) |

| ≥10 | 38 (63.3) |

| Not measured | 19 (31.7) |

Includes finger prick and laboratory-based test.

With regards to the presence of clinical features suggestive of a recent seizure, more than three-quarter of subjects (n = 46, 76.7%) presented with a decreased level of consciousness whereas foaming around the mouth (n = 22, 36.7%), tongue biting (n = 19, 31.7%) and urinary incontinence (n = 20, 33.3%) was evident in approximately one-third of subjects. Most subjects (n = 54, 90.0%) had manifested with two or more of these features. The presence of clinical features of focal neurological deficit was documented in 13 (21.7%) subjects.

Majority of subjects (n = 48, 84.2%) had one or more generalized seizures, whilst five (8.3%) subjects had focal seizures only. The seizure type was not reported in four (7.6%) subjects. The median (IQR) time to ED presentation after a seizure episode was 120 (51–244) minutes amongst the 33 (55.0%) subjects in whom the data was available. The median (IQR) time taken to return to baseline neurological function after the seizure was 46 (21–94) minutes amongst the 34 patients (56.7%) in whom the time was documented. Twenty-six (43.3%) subjects had a seizure that was witnessed by ED staff.

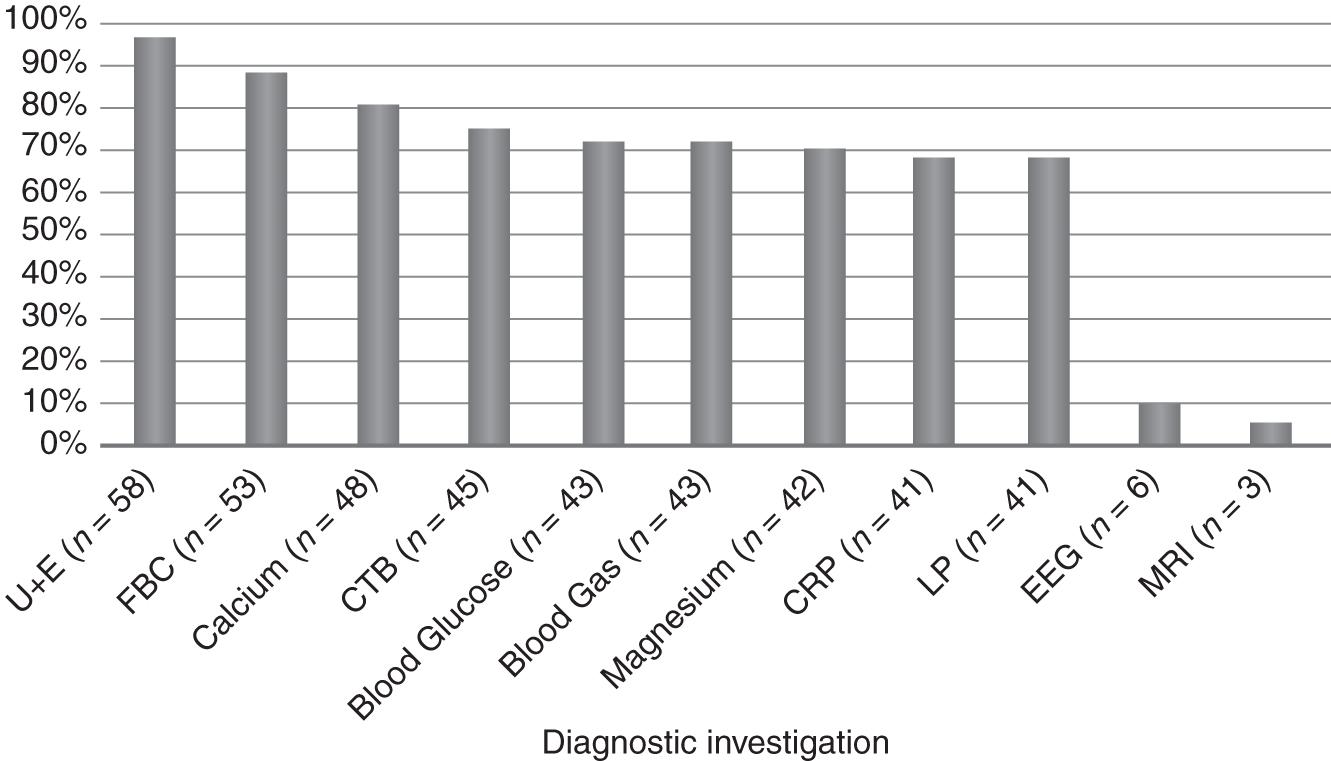

The proportion of study patients in whom various diagnostic investigations were performed in the ED are described in Figure 1. Among the 45 (75.0%) subjects that had a CT scan of the brain (CTB), 31 (68.9%) scans yielded positive findings, whereas, only 2 of the 41 lumbar punctures (4.9%) that were performed yielded positive findings. Cryptococcus neoformans was the organism that was identified in both cases.

Diagnostic investigations performed on study subjects

U + E = urea and electrolytes, FBC = full blood count, CTB = computed tomography scan of the brain, CRP = C-reactive protein, LP = lumbar puncture, EEG = electroencephalography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain.

Hypoglycaemia (n = 16, 26.7%) and intracranial ring- enhancing lesions (n = 10, 16.7%) were the commonest attributable aetiology of the seizure presentation (Figure 2). The suspected aetiology of the intracranial ring- enhancing lesions was attributed to neurocysticercosis (n = 2, 3.3%), toxoplasmosis (n = 2, 3.3%) and tuberculoma (n = 3, 5.0%), whilst the aetiology in the remaining three cases was not recorded. Other causes are described in Figure 2. With regards to long-acting anticonvulsants, phenytoin and sodium valproate were administered in the ED to 31 (51.7%) and 9 (15.0%) subjects, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Similar to the findings of earlier studies,(4,12,13) the most common age at presentation in this study was between 30 and 39 years. The higher proportion of males in this study was also comparable to other studies (14,15) but contrasted to the findings of a study conducted in the Western Cape, South Africa.(4) A study conducted in rural North-East of South Africa showed that males were more than twice as likely to develop active convulsive epilepsy (16) and generalized seizures were the predominant seizure type in over 80% of subjects in this study. Similarly, a study conducted in France reported that a first-episode seizure was twice as likely to be generalized than focal.(17) In contrast, partial seizures made up the majority (56%) of first-episode seizures in a study that was conducted in South India.(14)

Since the underlying aetiology of a first-episode seizure may be life-threatening, the substantial delay (median time of 2 h) in patient presentation to the ED is of concern. Lack of awareness, accessibility challenges and the inappropriate utilization of emergency medical services (EMS) by the public are possible reasons for this delay.(10)

In the work-up of a patient with a first-episode seizure, routine investigations such as full blood count, glucose, renal profile, electrolyte profile and toxicology screen are recommended as they may suggest the underlying aetiology and guide further management.(18) Venous blood gas analysis within the first hour has also been identified as a useful tool.(19) Since hypoglycaemia was the commonest cause of seizures in the current study and delays in treatment could potentially lead to permanent neurological disability,(17) it is concerning that the blood glucose was not documented in 28.3% of study subjects.

Of note, amongst study subjects in whom the HIV status was documented, 43.6% were HIV positive. This figure is more than double the current adult HIV prevalence rate (18.9%) in South Africa.(8) New-onset seizures have been reported in up to 20% of HIV-infected individuals.(20) Intracranial opportunistic infections, space-occupying lesions, metabolic derangements and antiretroviral drugs are common causes of seizures in individuals with HIV.(21) The high HIV prevalence amongst study subjects may also explain why the admission rate (56.7%) in this study was higher than previous reports of 15–46%.(12,13) These findings emphasize the importance of determining the HIV status of patients presenting with a first-episode seizure, especially in regions with a high burden of disease. Although the reason as to why the HIV status was not documented in 35% of subjects is not clear, a derangement in mental status post seizure and the inability to obtain consent may be possible reasons.

MRI is considered the imaging modality of choice in patients with new-onset seizures. However, due to its high cost and non-availability in many public hospitals, CTB is an alternative modality when neuroimaging is required.(15) The yield of CTB findings in our study was relatively high at 68.9%. Positive CTB findings ranged from 12% to 41% in other studies.(15,22) The higher yield in our study suggests the need to perform a CTB in all first-episode seizure patients with no obvious extracranial cause of the seizure.

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) guidelines state that emergency physicians need not prescribe long-acting anticonvulsants to patients with provoked or unprovoked first-episode seizures in the absence of brain disease or injury.(6) Compared to 2% in a study by Breen et al.,(12) anticonvulsants were administered to 66.7% of study subjects during their stay in the ED. The high number of intracranial lesions as detected on CTB was the compelling reason for the higher rate of anticonvulsant prescription in this study.

Following a first-episode seizure, the decision on whether to admit or discharge a patient can sometimes be challenging. The admission rate of 56.7% in this study was higher compared to other studies where the admission rate ranged between 15% and 46%.(12,13) This may be due to the high number of subjects with an underlying intracranial pathology. As per the ACEP guidelines, a patient who has regained full consciousness, has no residual neurological fallout, has normal vital signs and has no abnormality on appropriate investigative work-up (laboratory, ECG, CTB), may be discharged to the care of a responsible adult after an unprovoked first seizure.(6)

Limitations

Since this was a single-centre study with a relatively small sample size in a high HIV prevalent population group, our results may not be generalizable to other clinical settings. Other limitations that relate to studies that rely on data collection from medical records include inter-observer reliability, missing patient data and abstractor blinding to study hypotheses may also apply to this study.(23)

CONCLUSION

Hypoglycaemia and intracranial pathologies are common causes of first-episode seizures that must be considered in all patients. The late presentation of patients to the ED in this preliminary study is a major concern. Awareness programmes should be aimed at educating the public on the appropriate use of EMS and the importance of arranging urgent medical care for individuals with a first-episode seizure. Due to the high prevalence of HIV in South Africa, there is a need to develop local guidelines on the management of first-presentation seizures in HIV-positive as well as HIV-negative patients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SS-O: Responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; data collection, statistical analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting, writing, review, revision and approval of the manuscript.

FM: Contributed to the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and the drafting, writing, review, revision and approval of the manuscript.

AB: Contributed to the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and the drafting, writing, review, revision and approval of the manuscript.

AEL: Contributed to the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and the drafting, writing, review, revision and final approval of the manuscript.