INTRODUCTION

In December 2019 a patient with clinical viral pneumonia symptoms of unknown etiology was reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China [1]. Sequences analyses of bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid samples confirmed that the unknown pathogen was a novel coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [2]. This new respiratory tract disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 was named by the World Health Organization (WHO) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A previous study showed that COVID-19 can be transmitted from human–to–human [3]. By 28 February 2023, there were > 758,390,564 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases and 6,859,093 deaths worldwide [4]. Therefore, a rapid and precise diagnosis of COVID-19 patients is essential for disease prevention. Diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 RNA using the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has been the gold standard for confirming COVID-19 patients. RT-PCR is most frequently used to identify SARS-CoV-2, but RT-PCR has limitations that deserve our attention. Because the RT-PCR process is intricate and requires technical expertise, RT-PCR cannot be supported in areas with insufficient medical resources. In addition, RT-PCR is not suitable for large rapid screening because of the cost and time requirements. More importantly, the false-negative result is an important limiting factor for RT-PCR [5]. Because undiagnosed patients may have a significant role in disease epidemics, another diagnostic test is needed. For the above reasons, we must develop a quick, easy, affordable, and viable method to replace or supplement RT-PCR to confirm COVID-19.

Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 by antibody detection is widely used as an alternative to RT-PCR [6]. Compared to RT-PCR assays, antibody detection is usually easy to perform, rapid, low cost, and suitable for geographic regions without nuclei acid testing equipment. Indeed, an antibody test is more suitable for screening people, especially in the detection of asymptomatic and recovered patients. It has been reported that people who come into contact with asymptomatic cases can also be infected with SARS-CoV-2 [7,8], thus making it more difficult to control SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Compared to RT-PCR, antibody detection is advantageous in diagnosing asymptomatic and recovered patients [9]. Healthcare workers can estimate the time elapsed between infected cases and trace contact people based on IgM or IgG antibody detection. Detection of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 cannot only establish immunity, but can be used for diagnosis. SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing can be categorized into enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA), or chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIAs) [10–12]. The ELISA detection step is complex and requires a specially trained operator. Both CLIA and RT-PCR are constrained by the same issue (costly instruments). On-site testing for COVID-19 requires a rapid and high-throughput assay. Due to those requirements, a COVID-19 point-of-care test (POCT) cannot be satisfied by ELISA or CLIA. A rapid POCT is generally based on LFIA and has been used to detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus [13]. Numerous companies and laboratories have developed dozens of LFIA commercial kits, most of which qualify as a POCT; however, LFIA commercial kits still need careful clinical evaluation before being widely used.

Given these considerations, we conducted a clinical experiment to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a rapid antibody test kit based on a colloidal gold immunochromatographic assay (GICA). The rapid antibody test kit performance was evaluated using clinically confirmed positive or negative case samples. The purpose of the current study was to provide information on applying IgM or IgG rapid antibody tests for the diagnosis and prevention of COVID-19.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The Xiangyang No. 1 People Hospital was the principal institution for conducting clinical research experiments in this study. Ethical approval for IgG (2020GCP017) and IgM (2020GCP018) was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Xiangyang No. 1 People Hospital.

Populations and samples

From 9 March–20 May 2020 a total of 838 subjects from 3 qualified clinical trial institutions were enrolled (Chongqing Public Health Medical Treatment Center, Hubei Provincial Third People’s Hospital, and Xiangyang First People’s Hospital). The samples met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the collection and processing of samples complied with the requirements of the laboratory and product instructions; and (2) completing relevant information, including number, age, gender, and sample type. Samples were excluded for the following reasons: (1) severely dirty; and (2) microbial contamination. Serum or plasma samples were collected intravenously using conventional methods. If the test was performed within 5 days, samples were stored at 2-8°C. Otherwise, the samples were stored at -80°C. The number of times samples were frozen and thawed did not exceed three.

Clinical diagnostic criteria and RT-PCR assay

The identification of positive cases includes epidemiologic history and clinical manifestations. The clinical manifestations included the following: 1) fever and/or respiratory symptoms; 2) imaging features of new coronavirus pneumonia; 3) the total number of white blood cells was normal or decreased; and 4) the lymphocyte count was normal or decreased in the early stage of symptom onset. The confirmed cases had one of the following pieces of etiologic evidence: 1) real-time fluorescent RT-PCR detection of new coronavirus nucleic acid-positivity; and 2) viral gene sequencing, which is highly homologous to known new coronaviruses. SARS-CoV-2 was detected by RT-PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, sputum, or throat swabs. Two commercial RT-PCR kits were used to perform the test: DAAN GENE (Guangzhou, China); and Sansure Biotech (Changsha, China). All samples were examined in the three certified clinical trial institutions following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Colloidal gold-based immunochromatographic strip assay

We used the 2019-nCoV IgM antibody test kit (gold immunochromatographic assay [GICA]; Bioneovan Co., Beijing, China) and the 2019-nCoV IgG antibody test kit (GICA; Bioneovan Co.) for the rapid antibody diagnosis. According to the official guidelines issued by the Center for Medical Device Evaluation of the National Medical Production Administration, the specificity of our assay was determined by evaluating reactivity with common interfering factors. In addition, cross-reactivity tests were performed on other clinical samples obtained from individuals with infections other than SARS-CoV-2. Taken together, these results showed that our newly developed assay was highly specific for SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection and showed no cross-reactivity with other substances. The test strip was placed on a level surface of a workbench. Briefly, 10 μl of serum or plasma or 20 μl of whole blood was added to the sample loading area, followed by 70-100 μl (2 drops) of sample dilution buffer. The results presented were obtained after 10-15 min. The sample in which the C line (control) and T line (test) changed color was considered positive. If only the C line (control) was observed, the test was regarded as negative. If the C line (control) and T line (test) or C line (control) did not change color, the results were considered to be invalid.

Statistical analysis

The demographic characteristics between the clinically confirmed and negative control groups were compared. The Mann-Whitney U-test and χ 2 test were used to analyze the variables with a non-normal distribution and categorical variables, respectively. The clinical diagnostic results were used as controls to evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), kappa, and tge 95% confidence interval (CI) of the rapid tests. In addition, subgroup analysis was performed according to sample type and disease duration. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R version 3.4.3.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of enrolled participants

This study included 838 volunteers, of whom 296 were clinically diagnosed with COVID-19 and 542 were diagnosed as negative controls (Table 1). The median (IQR) age of the participants was 48 years (range, 33-63 years). The confirmed group was significantly older than the negative control group (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to gender. The number of confirmed patients with disease durations of 7 days, 8–14 days, and 15 days were 52 (17.6%), 100 (33.8%), and 144 (48.6%), respectively.

Characteristics of donors.

| Characteristics | Confirmed (n=296, %) | Control (n=542, %) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 51.65±17.81 | 45.83±19.15 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 145 (49.0) | 253 (46.7) |

| Female | 151 (51.0) | 289 (53.3) |

| Sample type | ||

| Plasma | 181 (61.1) | 317 (58.5) |

| Serum | 115 (38.9) | 225 (41.5) |

| Period from symptom onset | ||

| 0-7 days | 52 (17.6) | |

| 8-14 days | 100 (33.8) | |

| ≥15 days | 144 (48.6) | |

| Clinical trial institutions | ||

| Chongqing Public Health Medical Treatment Center | 117 (39.5) | 92 (17.0) |

| Hubei Provincial Third People’s Hospital | 133 (44.9) | 101 (18.6) |

| Xiangyang First People’s Hospital | 46 (15.5) | 349 (64.4) |

Diagnostic efficacy of IgM or IgG rapid antibody tests

The results of the colloidal GICA are shown in Table 2. Considering the clinical diagnosis results, we found 255 tests as true positives and 5 as false positives. In contrast, 537 IgM tests were true negatives and 41 were false negatives. The IgM test reached a sensitivity of 86.1%, specificity of 99.1%, PPV of 98.1%, NPV of 92.9%, and kappa of 0.88. Similarly, we found 256 tests to be true positives and 7 false positives. In contrast, 535 IgG tests were true negatives and 40 were false negatives. The IgG test sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and kappa were 86.1%, 99.1%, 98.1%, 92.9%, and 0.87, respectively. We showed that 281 tests were true positives when IgM and IgG were positive. Moreover, the sensitivity increased from 86.1% to 94.9% (95% CI, 91.8-97.1) and the kappa value increased from 0.87–0.93. We further stratified the test results based on sample type, and the plasma sample results were consistent with the overall results (data not shown).

Diagnostic performance of the immunochromatography assay versus RT-PCR.

| Positive | Negative | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive predictive value (95% CI) | Negative predictive value (95% CI) | All predictive values (95% CI) | Kappa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | 86.1 (81.7-89.9) | 99.1 (97.9-99.7) | 98.1 (95.6-99.4) | 92.9 (90.5-94.9) | 94.5 (92.7-96) | 0.8764519 | ||

| Confirmed group | 255 | 41 | ||||||

| Control group | 5 | 537 | ||||||

| IgG | 86.5 (82.1-90.2) | 98.7 (97.4-99.5) | 97.3 (94.6-98.9) | 93 (90.6-95) | 94.4 (92.6-95.9) | 0.8740639 | ||

| Confirmed group | 256 | 40 | ||||||

| Control group | 7 | 535 | ||||||

| IgM/IgG | 94.9 (91.8-97.1) | 97.8 (96.2-98.9) | 95.9 (93-97.9) | 97.2 (95.5-98.5) | 96.8 (95.3-97.9) | 0.9293216 | ||

| Confirmed group | 281 | 15 | ||||||

| Control group | 12 | 530 | ||||||

| RT-PCR | 96.3 (93.4-98.1) | 100 (99.3-100) | 100 (98.7-100) | 98 (96.5-99) | 98.7 (97.7-99.3) | 0.971027 | ||

| Confirmed group | 285 | 11 | ||||||

| Control group | 0 | 542 |

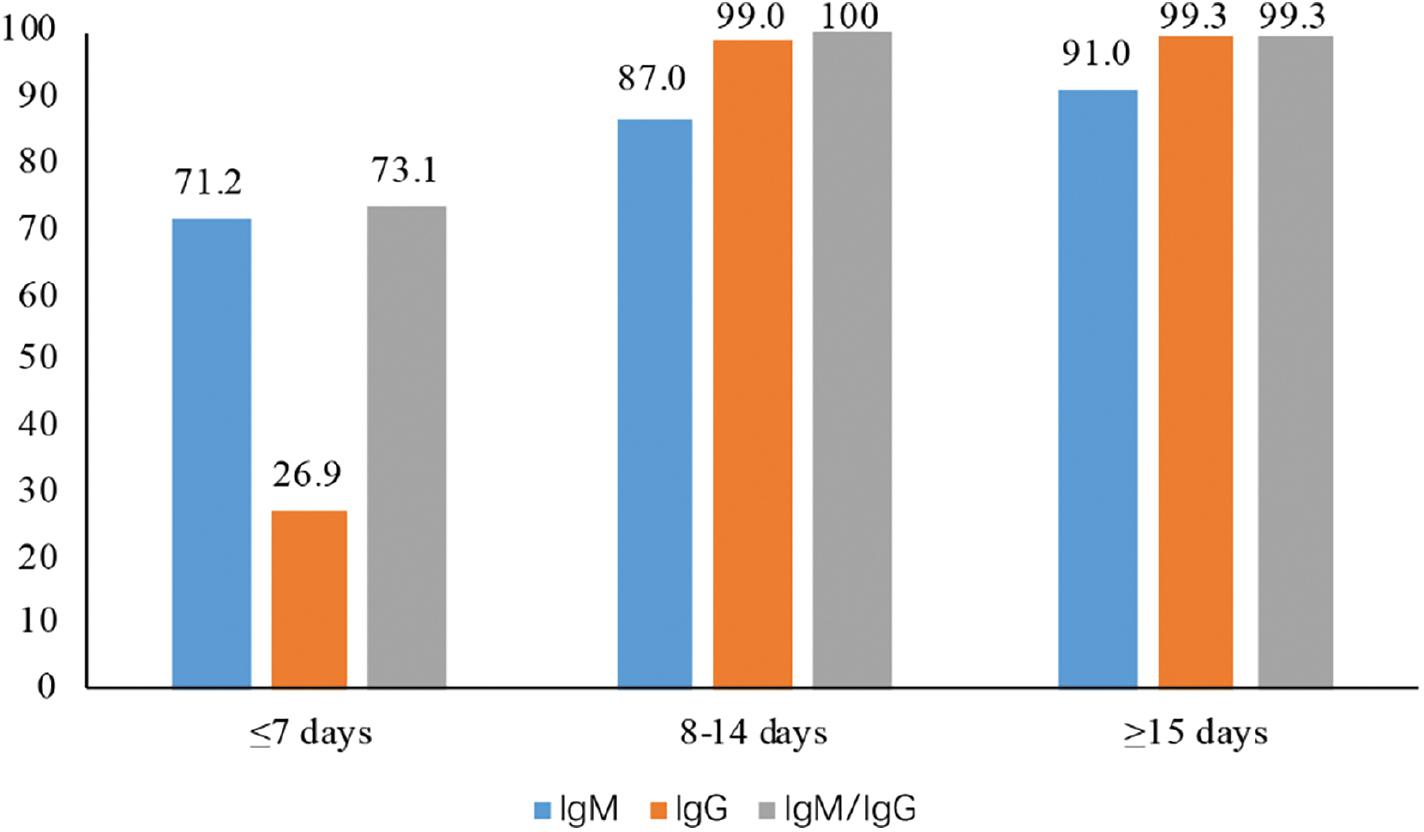

Sensitivity of IgM or IgG rapid antibody tests according to the time from symptom onset

Based on the period from the onset of symptoms, the disease duration was divided into the initial stage (1-7 days after onset), intermediate stage (8-14 days), and recovery period after treatment (> 15 days). As shown in Table 3 and Fig 1, the positive IgM or IgG rate gradually increased as the disease progressed. The positive IgM rate increased from 71.2% in the initial stage to 87.0% and 91.0% in the middle and recovery periods (P=0.002), respectively. IgG positivity was initially low, at only 26.9 %. During the interim and recovery periods, IgG positivity increased to 99.0 and 99.3 %, respectively (P<0.001). For either IgM- or IgG-positive patients, the combination of IgM and IgG significantly improved the sensitivity of the test, especially in the initial stage. The positive IgM and IgG rate was 71.2% and 26.9% in the initial stage, respectively, and increased to 73.1% when the two parameters were combined.

The positive immunochromatography assay rate in different subgroups. Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Diagnostic positive immunochromatography assay rate versus RT-PCR according to the period from symptom onset.

| Initial stage (1-7 days) | Intermediate stage (8-14 days) | Recovery stage (> 15 days) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IgM (n, %) | |||

| Positive | 37 (71.2) | 87 (87) | 131 (91) |

| Negative | 15 (28.8) | 13 (13) | 13 (9) |

| IgG (n, %) | |||

| Positive | 14 (26.9) | 99 (99) | 143 (99.3) |

| Negative | 38 (73.1) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.7) |

| IgM/IgG (n, %) | |||

| Positive | 38 (73.1) | 100 (100) | 143 (99.3) |

| Negative | 14 (26.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) |

| RT-PCR (n, %) | |||

| Positive | 42 (80.8) | 99 (99) | 144 (100) |

| Negative | 10 (19.2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

Diagnostic efficacy of rapid antibody tests in RT-PCR false-positive results

Each of the 296 positive participants in this study received a clinical diagnosis and underwent RT-PCR testing. According to the clinical diagnosis results, 11 people had COVID-19 based on a clinical diagnosis but the nucleic acid test was negative. In the real-time RT-PCR negative group, four individuals had positive results for rapid antibody tests. As summarized in Table 3, no patient was > 15 days from the onset of symptoms, and the positivity rate increased from < 7 days (30.0%) to 8-14 days (100.0%). This difference was not statistically significant for IgM or IgG (P=0.364 and p=0.273, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Serological diagnostic tests, such as the rapid detection of antibodies or viral antigens, have been extensively used in many clinical laboratories. Due to the lack of comprehensive and reliable clinical data about the clinical performance of these serologic diagnostic tests for COVID-19 [14], we evaluated a convenient colloidal gold immunochromatography assay to detect IgM and/or IgG specific for SARS-CoV-2. The study consisted of 838 samples from 3 qualified clinical institutions, including 296 positive and 542 negative cases. The sample size was greater compared to other studies [15–19], thus enabling us to evaluate the clinical performance of GICA in detecting COVID-19 more objectively.

Our research showed that the 2019-nCoV IgM/IgG rapid antibody test (GICA) kit for detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibody reached a high sensitivity of 94.9%, specificity of 97.8%, PPV of 95.9%, NPV of 97.2%, and kappa of 0.93. The results indicated that GICA could be used to complement the diagnosis of COVID-19. In addition, the sensitivity of detecting IgM/IgG was higher than that of detecting IgM or IgG alone. Therefore, we suggested that the subjects should include the detection of both IgM and IgG. The sensitivity of LFIA is lower than ELISA [20]; however, through redesigned methods, GICA achieved similar sensitivity to ELISA [21]. Therefore, it is achievable to develop GICA with high sensitivity similar to ELISA; however, the antibody test method shows false-positive result detection of SARS-CoV-2 [22]. In our study, 12 subjects had false-positive results, including 5 (1.9%) IgM and 7 (2.7%) IgG false-positive results. Furthermore, more research was needed to verify the specificity of IgM or IgG. The high proportion of convalescent patients in the study may be an important reason for the GICA assay high sensitivity and specificity. Nevertheless, this method still requires improvement.

In addition to describing GICA clinical performance in detecting COVID-19, we also monitored SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamic changes. After being infected with SARS-CoV-2, IgM antibodies are produced first, followed by IgG antibodies [23,24]. COVID-19 patients have detectable IgM antibodies within 2-3 days after symptom onset and peak at 2-3 weeks [3,25]. IgG antibody increases from 10-14 days after symptom onset, increasing to 4-5 weeks, then decreases at 5-6 weeks, after which IgG levels are stable [26]. According to symptom onset, the samples were divided into 3 groups (≤7 days, 8-14 days, and ≥15 days), then antibodies were detected by GICA. In our study the detection rate of IgM and IgG was increased within 15 days after symptoms onset. As in other studies, the antibody diagnostic sensitivity increased with time after the onset of symptoms [27–29]. In the early stages, the sensitivity of IgM was 71.2% and IgG was only 26.9% within 0-7 days after symptom onset. The results suggest that IgM occurred in the early stage after being infected with SARS-CoV-2. The detection rate of IgM was 71.2%. Overall, the diagnosis of COVID-19 through antibody tests may not be a good choice in the early stage. As time passed, the diagnostic sensitivity of IgM/IgG reached 99.3 % after symptom onset ≥15 days. Therefore, GICA has the potential to be a reliable diagnostic method of detecting SARS-CoV-2 after symptom onset ≥ 15 days. Other studies also reached a similar conclusion [30–32].

Although many studies have shown that LFIA has a better application prospect for detecting COVID-19, some questions about practical application still need to be answered. Usually, IgG antibody is produced later than IgM antibody following pathogen invasion. For example, IgM-positivity indicates a recent infection of SARS-CoV-2 and IgG-positivity indicates past SARS-CoV-2 infections; however, the seroconversion of COVID-19 is still a controversial topic. Studies have pointed out that IgM and IgG does not have special seroconversion in COVID-19 patients [33]. Specifically, IgG appeared earlier than IgM in some COVID-19 patients [27,34]. This phenomenon was also noted in our study. Within 7 days of symptom onset, a COVID-19 patient was IgG-positive but IgM-negative (data not shown). Further research is needed to explore the reasons underlying this phenomenon.

Antibody tests, combined with RT-PCR detection, may help improve sensitivity, particularly in people who present after symptom onset [28,35]. This study evaluated the performance of the rapid antibody test (GICA) using COVID-19 samples that were not detected by nucleic acid tests. In our study the nucleic acid test results of 11 patients were negative, but the clinical diagnoses were positive. Furthermore, 4 of 11 people with negative RT-PCR testing were rapid antibody test (GICA)-positive. Our research confirmed that rapid antibody test (GICA) might complement RT-PCR detection of COVID-19; however, our study was limited by the nucleic acid-negative sample size. Therefore, the rapid antibody test (GICA) capacity to detect false-negative cases in RT-PCR warrants complete evaluation.

To further evaluate the impact of concomitant disease on the sensitivity and specificity of rapid antibody tests (GICA) in the detection of COVID-19, more data on co-morbidities among the subjects is needed. For example, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus are important factors that lead to false-positive results based on the rapid antibody test (GICA) of COVID-19 [36]. We also need a more detailed division of the COVID-19 disease duration after symptom onset, which will facilitate insight into the dynamic antibody changes after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In conclusion, our study described the clinical performance of rapid antibody tests (GICA) in detecting COVID-19 and monitoring the dynamic changes of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after symptom onset. Our data indicate that GICA has the potential as a complement to RT-PCR for COVID-19 diagnosis and screening. In addition, GICA can also provide essential information about the immunoreaction of COVID-19 patients. In conclusion, the rapid antibody test (GICA) contributes to the epidemiologic investigation of COVID-19 and helps prevent disease transmission.