1. INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas), whether malignant or benign, are extremely rare. Only 29 cases, including the present case, have been reported in the literature between 1996 and 2020 [1–28]. Patients reported with pancreatic PEComas have ranged in age from 17-74 years, with a mean age of 46.9 years [1–28]. Females outnumber males, which appears to be connected to sex hormones [19]. PEComas are characterized morphologically by an epithelioid cell population [1]. In addition, the expression of melanocytic and myeloid markers, such as HMB-45 and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), respectively, have a unique and distinctive profile. Angiomyolipoma (AML), clear cell “sugar” tumor (CCST) of the lung, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), and other PEComas with comparable histologic and immunohistochemical features comprise the PEComa family [29].

Surgery has been the most widely used treatment for PEComas [30], despite data showing that mTOR inhibitor therapy without surgery is highly effective [26]. Herein we report a case of a pancreatic PEComa that was misdiagnosed preoperatively as a pancreatic malignant tumor.

2. CASE DESCRIPTION

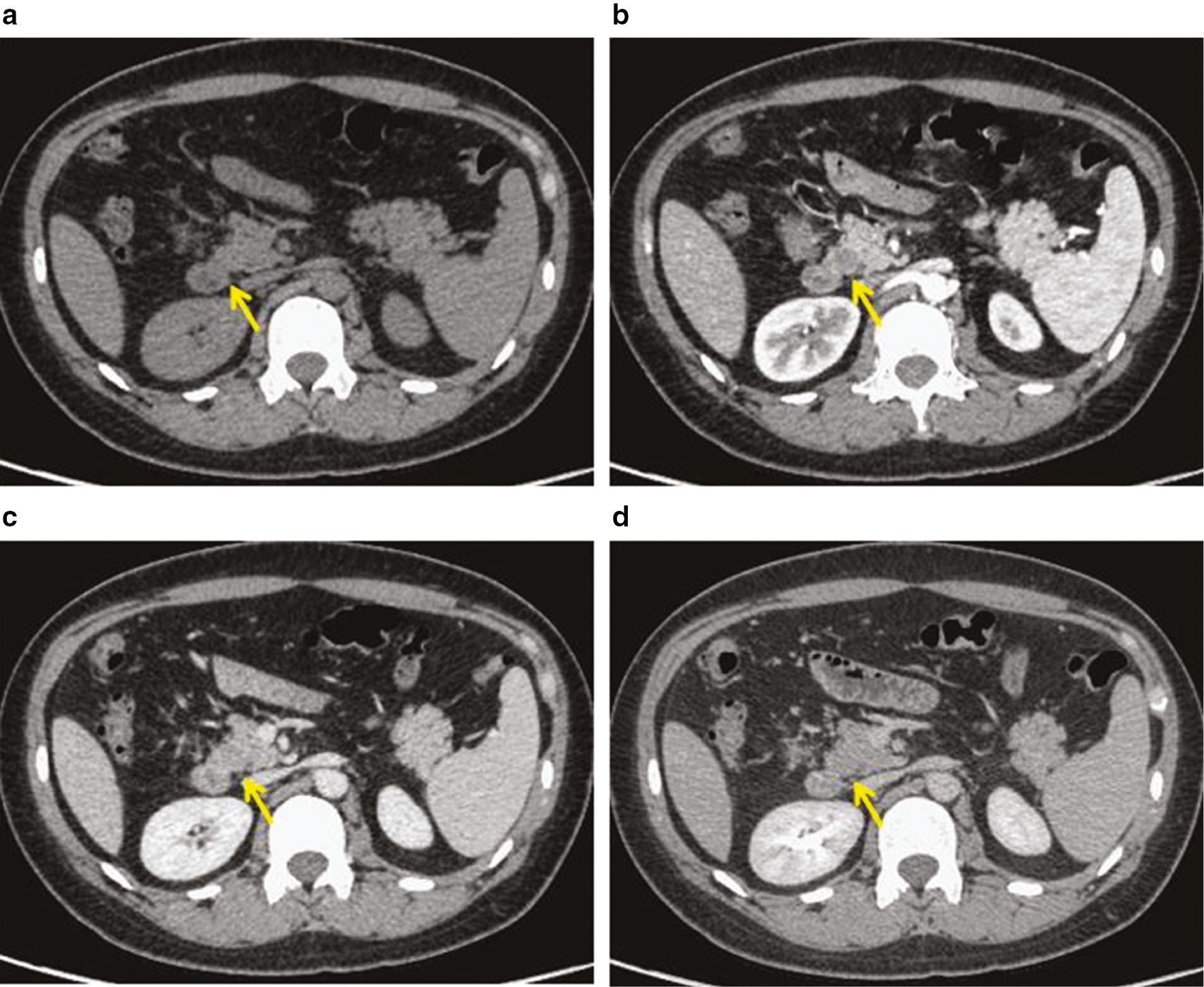

A 41-year-old female was admitted to the hospital preoperatively for resection of a hysteromyoma. Preoperative imaging revealed a pancreatic mass in the uncinate process. The patient did not smoke cigarettes and did not abuse alcohol. She had no family history of cancer, diabetes, or tuberous sclerosis (TSC). The CA-125 was elevated to 428 U/L (normal, 24-158 U/L), although other tumor markers, including CA-199, were normal. Other hematologic, serologic, and biochemistry laboratory tests indicated no abnormalities. A plain CT scan of the abdomen showed that the morphology and density of the mass were indistinguishable from normal pancreatic parenchyma ( Figure 1a ). The pancreatic duct was not dilated. There were no enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes and the peripancreatic space was clearly demarcated. There was a relatively low density nodule, approximately 10 mm in diameter in the pancreatic uncinate process, during the arterial phase ( Figure 1b ). The nodule had a significantly lower density than the surrounding pancreatic tissue during the portal venous phase ( Figure 1c ) and was iso-dense compared to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma during the delayed phase ( Figure 1d ).

Pancreatic PEComa on contrast-enhanced abdominal CT.

(a) Plain CT scan. (b) Arterial phase. (c) Portal venous phase. (d) Delayed phase. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a relatively well-demarcated mass, measuring approximately 10 mm in diameter, and located in the uncinated process of the pancreas (arrows). The pancreatic PEComa was slightly enhanced during the arterial phase and almost enhanced to the same degree as the surrounding pancreatic tissue during the portal venous and delayed phases.

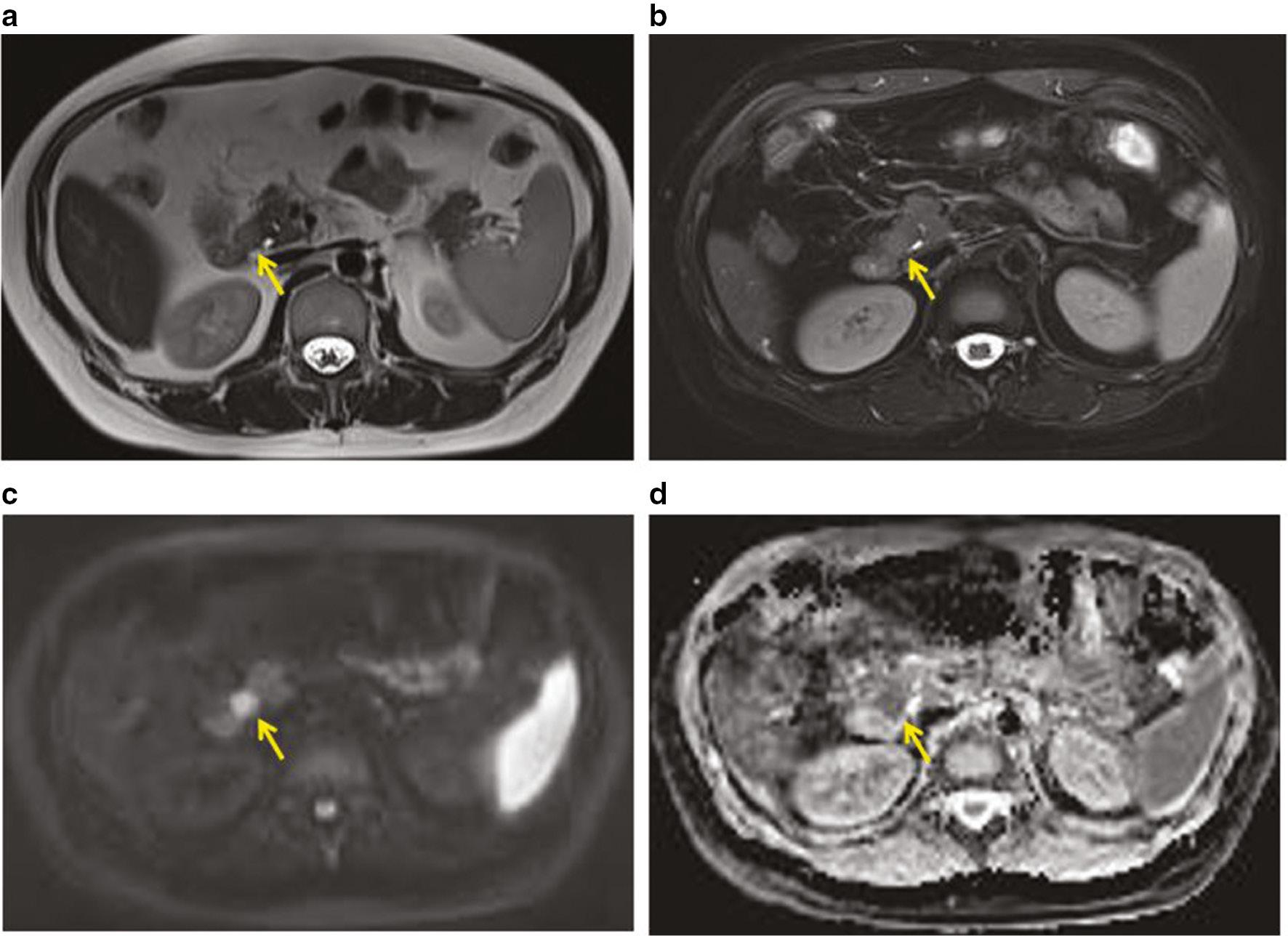

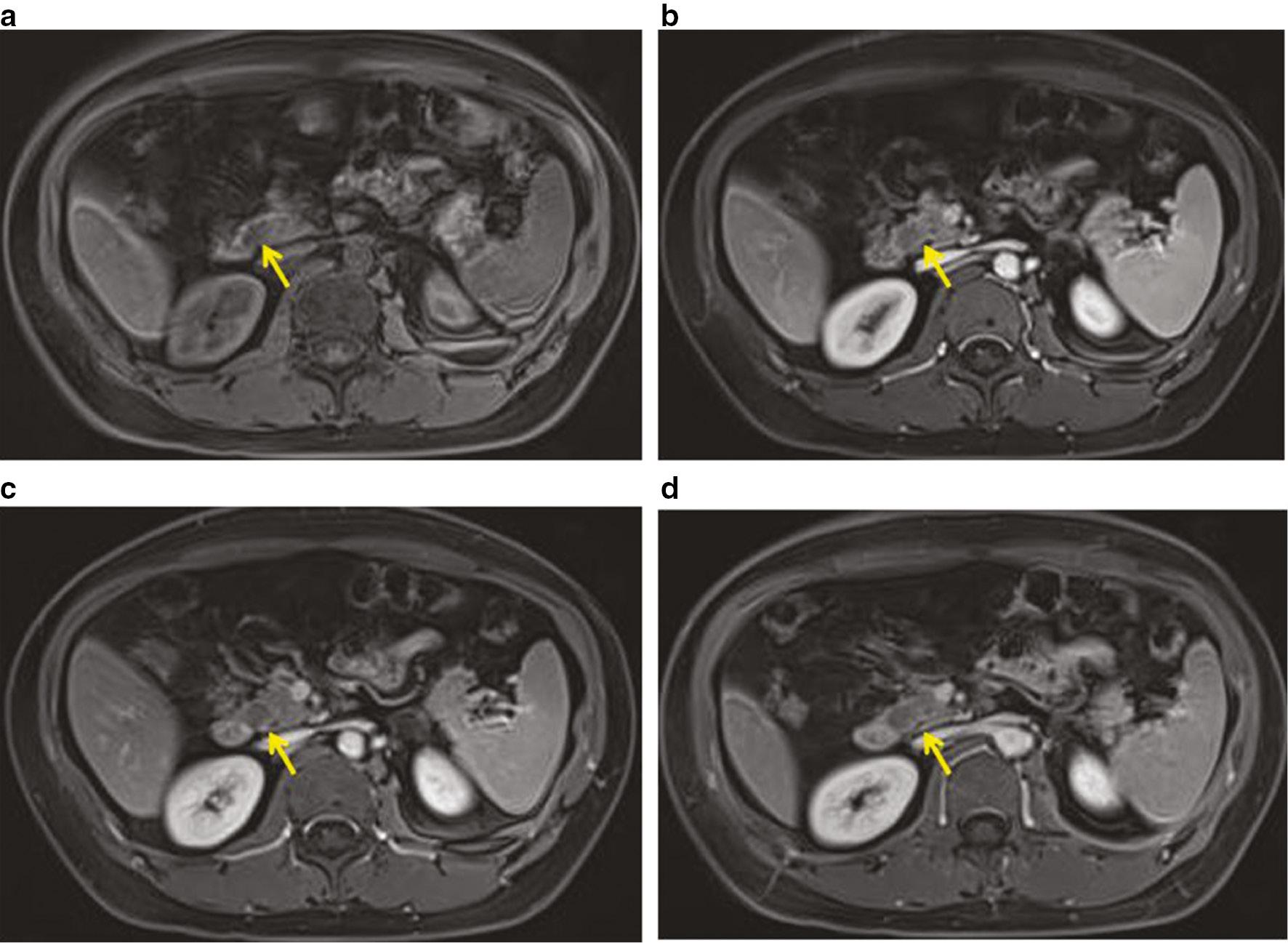

A 3.0 T scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a body coil was used for preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which revealed a round, solid mass in the uncinate process of the pancreas. The mass was slightly hyperintense and fat-saturated on T2-weighted images ( Figure 2a, 2b ), hyperintense on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and hypointense on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping ( Figure 2c, 2d ). Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI revealed a slightly homogeneous, enhanced tumor ( Figure 3a–3d ). The tumor was hypovascular compared to the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma without an enhanced capsule.

Pancreatic PEComa on plain scan of MRI.

(a) T2-weighted imaging (b) Fat-saturated T2-weighted imaging (c) Diffusion weighted imaging; (d) Apparent diffusion coefficient map. The pancreatic tumor was not clearly visible (arrowhead) in 2a and 2b. The tumor was clearly characterized as hyperintense in 2c and hypointense in 2d.

Pancreatic PEComa on contrast-enhanced abdominal MRI.

(a) Plain scan. (b) Arterial phase. (c) Portal venous phase. (d) Ultra-delayed phase. (a) There was a round, hypointense nodule (arrowhead) in the pancreatic uncinate process. (b) This solid nodule demonstrated slow homogeneous enhancement. (c) The nodule revealed gradual and slowly decreasing enhancement with a well-defined margin. (d) The nodule showed hypointense compared to the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma.

Because the patient was suspected a malignant pancreatic neoplasm, she underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy with complete extirpation of the mass. A solid tumor 3×3×2cm in size was noted in the uncinate process of the pancreas intraoperatively. The tumor had a hard texture and no adhesions with the surrounding pancreatic tissues.

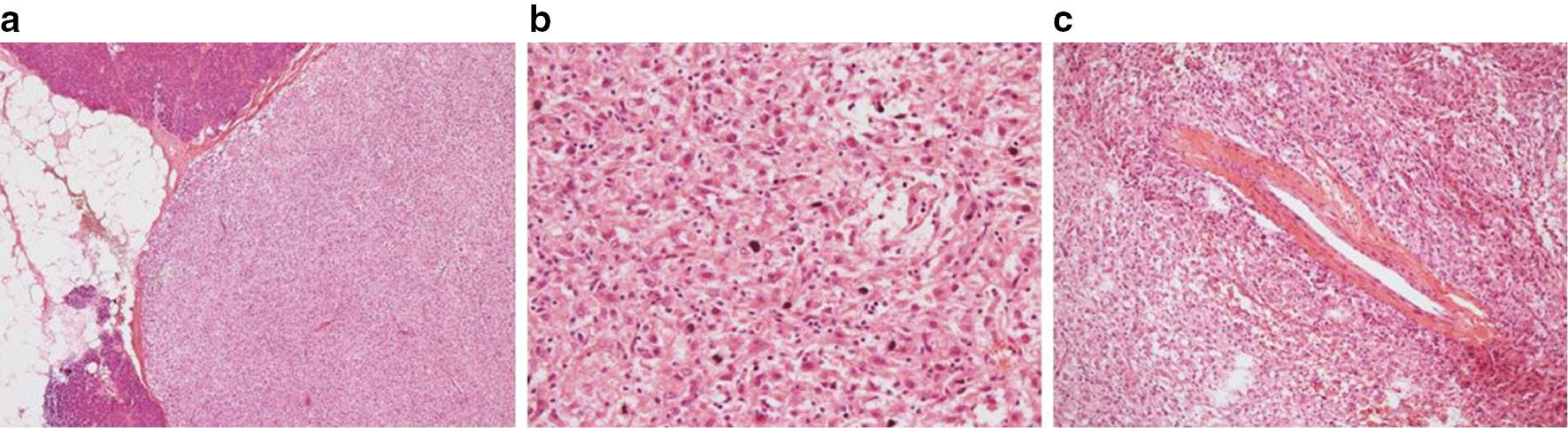

Gross examination showed a well-demarcated, solid, grey, soft nodule with a fibrous capsule. Neither hemorrhage nor necrosis was noted. The microscopic examination demonstrated a uniform population of large epithelioid cells distributed in sheets ( Figure 4a, 4b ). The epithelioid cells were abundant with granular eosinophilic-to-clear cytoplasm ( Figure 4b ). The tumor was traversed by thick-walled vessels that were identified focally ( Figure 4c ). The tumor cells showed round-to-oval nuclei, sometimes with a prominent nucleolus and nuclear pleomorphism. There was no local or lymph node metastases and the surgical margins were negative.

Microscopic examination of a pancreatic PEComa.

(a) Microscopy shows a well-circumscribed tumor with a fibrous capsule. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×40. (b) The tumor forms sheets of pale, epithelioid cells with abundant granular eosinophilic-to-clear cytoplasm, including the sediment of melanin. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×200. (c) Thick-walled vessels were embedded in the nodule. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×100.

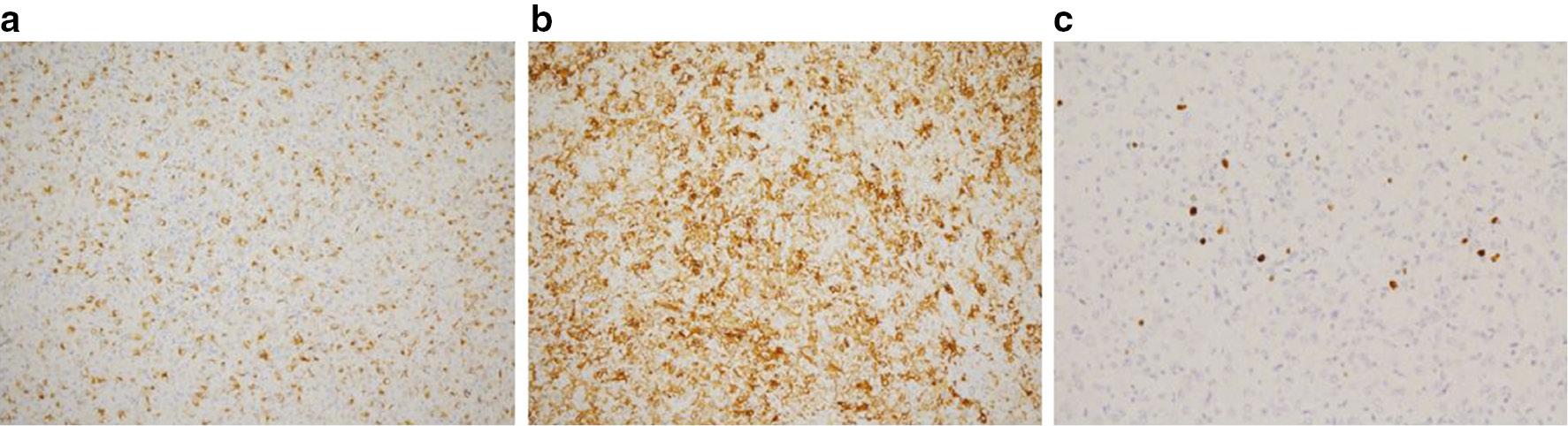

The immunohistochemistry results were as follows: HMB-45 (+) [ Figure 5a ]; SMA (+) [ Figure 5b ]; melan-A (+); Ki67 (3%) [ Figure 5c ]; vimentin (+); CD56 (+); Syn (−); CK (−); CD34 (−); LCA (−); S-100 (−); SOX10 (−); calretinin (−); MyoD1 (−); and myogene (−).

Immunohistochemistry of a pancreatic PEComa.

(a) HMB-45 strongly stained the cytoplasm of the majority of epithelioid cells. (b) Tumor cells expressed the smooth muscle marker, α-SMA. (c) The Ki67 labeling index was 3%. Original magnification ×200.

No metastases or other abdominal lesions were noted during the laparotomy. Ten months after surgery, the patient was doing well with no evidence of tumor recurrence. No abnormalities were noted during the pelvic follow-up evaluation.

3. DISCUSSION

Primary pancreatic PEComas are extremely rare, with only 29 cases, including the present case, reported in the literature between 1996 and 2020 [1–28]. The biological characteristics and histologic origin of pancreatic PEComas, as well as other sites affected, remain an enigma [30, 31]. Clinical data, including imaging examinations before treatment, are shown in Table 1 . Although surgery has been the most widely used treatment for a long period of time [30], the optimal treatment for pancreatic PEComas is a matter of debate. Zizzo et al. [24] suggested that patients should have a physical examination and abdominal CT scan every 12 months if they are in good general health without symptoms or radiologic signs of invasion [32], or tumors are classified as benign by endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). Furthermore, use of an mTOR inhibitor as a novel treatment method to treat a pancreatic PEComa was recently reported to be successful [26].

Summary of reports of pancreatic PEComas.

| Case | Diagnosis | Age | Gender | Symptoms | EUS | CT | MRI | Surgery performed | Follow-up (months) | Recurrence or metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zamboni/1996 | Clear cell “Sugar” tumor | 60 | F | Abdominal pain | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes | 3 | None |

| Heywood/2004 | Angiomyolipoma | 74 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 69 | None |

| Ramuz/2005 | “Sugar” tumor | 31 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 9 | None |

| Perigny/2008 | PEComa | 46 | F | Diarrhea | n/a | Yes | n/a | Yes | 3 | None |

| Hirabayashi/2009 | PEComa | 47 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 | None |

| Baez/2009 | PEComa | 60 | F | Abdominal bulge | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 7 | None |

| Zemet/2011 | PEComa | 49 | M | Fever, Cough, Malaise | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 10 | None |

| Nagata/2011 | PEComa | 52 | M | Abdominal pain | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes | 39 | Liver |

| Xie/2011 | PEComa | 58 | F | Abdominal pain | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes | 5 | None |

| Finzi/2012 | PEComa | 62 | F | None | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 5 | None |

| Singh/2012 | Solitary Lymphangioleiomyoma of Pancreas | 38 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | 12 | None |

| Al-Haddad/2013 | PEComa | 38 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | n/a | n/a |

| Okuwaki/2013 | PEComa | 43 | F | Abdominal pain, Abdominal mass | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 7 | None |

| Mourra/2013 | PEComa | 51 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 | Liver |

| Tummala/2013 | PEComa | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes | n/a | n/a | No | n/a | n/a |

| Kim/2014 | Primary Mesenchymal Tumors of the Pancreas | 31 | F | None | n/a | n/a | n/a | Yes | 63 | None |

| Petrides/2015 | PEComa | 17 | F | Melena | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 18 | None |

| Wei/2016 | PEComa | 58 | F | None | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 18 | None |

| Jiang/2016 | PEComa | 50 | F | None | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 | None |

| Mizuuchi/2016 | PEComa | 61 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 144 | None |

| Collins/2016 | PEComa | 54 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | 27 | None |

| Hartley/2016 | PEComa | 31 | F | None | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | n/a | n/a |

| Zhang/2017 | PEComa | 43 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | n/a | Yes | 18 | None |

| Zizzo/2017 | Primary PEComa | 68 | M | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | n/a | No | 13 | None |

| Hong/2018 | Malignant PEComa | 35 | F | jaundice and anorexia | Yes | n/a | n/a | Yes | n/a | Lymph node metastasis |

| Gondran/2019 | PEComa | 17 | M | weight loss, asthenia and flu-like syndrome | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 42 | None |

| Uno/2019 | PEComa | 49 | F | None | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 | None |

| Ulrich/2020 | PEComa | 49 | F | Abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n/a | None |

| Present case | PEComa | 41 | F | none | n/a | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 | None |

n/a: not available.

Patients with pancreatic PEComas have been reported to range in age from 17-74 years, with a mean age of 46.9 years. Women outnumber males (82.76% [24/29]) by a wide margin. Jiang et al. [19] suggested that PEComas may be associated with sex hormones. Pancreatic PEComas are characterized clinically by abdominal discomfort (51.72% [15/29]), although a significant proportion of patients with vague symptoms are identified incidentally during health screenings or follow-up tests for other medical conditions. As a result, making an accurate diagnosis solely based on the clinical presentation is challenging. The majority of pancreatic PEComas are benign, with just three malignancies recorded in the literature to date [8, 13].

Because just one patient with a pancreatic has been recorded with a history of tubular sclerosis complex (TSC), the relationship between PEComas and TSC warrants continued research. Specifically, the link between pancreatic PEComas and TSC may not be as significant as previously thought, despite evidence of TSC1 or TSC2 gene inactivation [29, 31].

Microscopic studies the pancreatic PEComa from our patient, like earlier reports, revealed a cellular, solid, homogenous tumor with a well-circumscribed boundary. Large epithelioid cells with copious granular eosinophilic-to-transparent cytoplasm made up the structure. Fascial or laminar distribution in sheets with capillaries were noted. The nuclei were polymorphic, typically eccentric, and occasionally with a conspicuous nucleolus, cytoplasmic, or nuclear inclusions. Based on immunohistochemistry staining, the expression of muscle (α-SMA and desmin) and melanocytic markers (HMB-45 and melan A) are diagnostic of PEComa, especially HMB-45 [30].

To date, radiologic features of PEComa have been reported independently in the literature. There have been 29 cases of pancreatic PEComas reported, including the current case, 25 of which have imaging data ( Table 2 ). The tumors had a round or round-like appearance (69.57% [16/23]), were solid (86.96% [20/23]), and well-demarcated (80.00% [16/20]). In almost all cases (96.00% [24/25]), the tumors were intrapancreatic. The uncinate process and head of the pancreas were the most frequently involved site (56.00% [14/25]). It was difficult to detect the tumor using endoscopic US without B-mode (power)-Doppler or enhancement in one patient. The pancreatic PEComas had a hard tissue appearance on elastography in two patients and the tumors were iso-enhanced on contrast-enhanced low mechanical index endosonography in two patients. It was difficult to detect the tumor on CT without enhancement in 3 patients. Significantly enhanced (46.15% [6/13]) and not significantly enhanced (53.85% [7/13]) tumors appeared in the multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) arterial phase. MRI demonstrated no cases without enhancement. Two tumors were clearly hyperintense on DWI and hypointense on ADC mapping. According to Folpe et al. [32] 6 features of tumors were defined as ≪ worrisome ≫lesions: > 5 cm; infiltrative growth pattern; high nuclear grade and cellularity; mitotic rate > 1/50 high-power fields; necrosis; and vascular invasion. With respect to our imaging findings, 9 were large (37.50% [9/24]) and 13 were heterogeneous (65% [13/20]). Of the 3 tumors that appeared to have vascular invasion on CT imaging, only 1 was shown to have vascular invasion on microscopic examination. One patient had regional lymph node enlargement. Pancreatic duct dilatation, pancreatic duct displacement, and bile duct dilatation were occasionally noted on endoscopic US, CT scans, and MRI.

Summary of radiological characteristics of pancreatic PEComas.

| Imaging findings | Pancreatic PEComas |

|---|---|

| Texture (n=23) | |

| Solid | 20(86.96%) |

| Cystic | 3(13.04%) |

| Shape (n=23) | |

| Round/round-like | 16(69.57%) |

| Irregular | 7(30.43%) |

| Demarcation (n=20) | |

| Well-demarcated | 16(80.00%) |

| Not well-demarcated | 4(20.00%) |

| Size (n=24) | |

| Large | 9(37.50%) |

| Not large | 15(62.50%) |

| Origin (n=25) | |

| Uncertain | 1(4.00%) |

| Intrapancreatic | 23(96.00%) |

| Head/uncinate process | 14(56.00%) |

| Body | 7(24.00%) |

| Tail | 2(8.00%) |

| Homogeneity (n=20) | |

| Homogeneous | 7(35.00%) |

| Heterogeneous | 13(65.00%) |

| Calcifications | 2(10.00%) |

| Bleeding | 1(5.00%) |

| Necrosis | 1(5.00%) |

| Others | 9(45.00%) |

| Significant enhancement in the arterial phase on MDCT (n=13) | |

| Yes | 6(46.15%) |

| No | 7(53.85%) |

In our case the tumor had a small, solid, hypovascular nodule on the CT scan and MRI. We investigated use of ultra-long, time-delayed phase imaging; however, the findings of pancreatic PEComas have not been described in the literature. Ultra-long, time-delayed phase acquisition was performed at 7 min. On dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images, the solid mass exhibited slow, homogeneous enhancement during the arterial phase. The tumor was hypointense compared to adjacent pancreatic parenchyma during the ultra-long, time-delayed phase. The signal intensity reflected the degree of impeded diffusion of water molecules on DWI. In our study the pancreatic PEComa showed significantly restricted diffusion [33]. Therefore, DWI may be valuable for detection of pancreatic lesions.

Because of the exceedingly rare and predominantly benign behavior of pancreatic PEComas, the differential diagnosis may include primary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, an ectopic accessory spleen, and metastatic tumors. Although ductal adenocarcinomas share a hypoattenuated or hypointense mass on contrast-enhanced CT or MRI with PEComas, the former is often associated with an elevated CA19-9, and morphologic abnormalities, including obstruction and/or dilatation of the distal main pancreatic duct and atrophic distal pancreatic parenchyma [34, 35]. Due to the hypervascular lesion in enhanced images, especially in the arterial phase, classical NETs are not difficult to differentiate from PEComas. Solid pseudopapillary tumors are mostly cystic and solid lesions with a high incidence of calcifications [36, 37]. Continuous enhancement is noted in enhancement with an enhanced capsule [36]. An accessory spleen usually appears as an isolated asymptomatic abnormality and has clinical significance in some rare situations. The accessory spleens are almost all located within 3 cm of the dorsal aspect of the pancreatic tail and the enhancement patterns on contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are similar to the spleen [38, 39]. Most of the metastatic tumors show annular enhancement. The degrees of enhancement vary based on the nature of the primary tumor [26, 30].

In conclusion, endoscopic US, CT, and MRI should be fully utilized to assist physicians with the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic PEComas. We believe that radiologists should consider pancreatic PEComas as a diagnosis or differential diagnosis if a round or round-like, solid, well-defined pancreatic mass that is hyperintense on DWI and hypointense on ADC mapping and other radiologic features. Additional research is needed to understand the biological aspects of pancreatic PEComas in a larger population.