Introduction

Antiplatelet therapy is a cornerstone of treatment for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), particularly after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1]. Multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that antiplatelet therapy significantly decreases the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with ACS in both the short and long term [1]. However, antiplatelet therapy is also associated with increased risk of bleeding in patients with ACS [2], and bleeding events in patients with ACS have been found to be independently predict adverse outcomes [3–9]. Beyond antiplatelet therapy, a previous study has suggested that aging increases the risk of bleeding [10, 11]. Although almost 50% of patients with ACS are ≥75 years of age [12], older patients are often excluded from randomized controlled studies [13, 14]. The risk scores currently used to predict risk of bleeding therefore might be unsuitable for older patients with ACS [15, 16]. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the incidence of bleeding and related risk factors, and the association between in-hospital bleeding and adverse outcomes in patients above 75 years of age.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

In this retrospective cohort study, a total of 962 patients with ACS above 75 years of age hospitalized in the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University between January 2012 and December 2016 were enrolled. Patients with ischemic stroke or cerebrovascular events within 3 months, a history of trauma within 3 weeks, a history of surgery and active visceral hemorrhage were excluded from the study. Those missing important clinical data were also excluded (Figure 1). Patients who met the inclusion criteria (n=922) were divided into two groups according to the presence or absence of bleeding events.

Definitions and Endpoints

The primary endpoint in our study was defined by in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and in-hospital bleeding events. In-hospital MACE included all-cause mortality, severe heart failure and stroke. According to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria [17], BARC type 2 and 3 were included as in-hospital bleeding events. BARC type 2 was defined as clinically overt hemorrhage requiring medical attention, whereas BARC type 3 was defined as bleeding with a hemoglobin decrease of at least 3 g/dL, requiring transfusion or surgical intervention, including gastrointestinal bleeding, respiratory bleeding or genitourinary bleeding. Renal insufficiency was defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Stroke was defined by the sudden onset of focal neurological deficits resulting from either infarction or hemorrhage in the brain. Severe heart failure was defined by grade III or IV heart dysfunction according to the New York Heart Association classification.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as number (and percentage) and were compared with chi-squared tests (Pearson χ2 or Fisher probabilities). Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD and were compared with the Student t-test if the data were normally distributed. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are presented as median (and interquartile range) and were compared with non-parametric tests. Odds ratios (OR) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Univariate factor logistic regression was used to analyze risk factors associated with bleeding during hospitalization. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to define independent risk factors for in-hospital bleeding after adjustment for age, sex, hypertension history and atrial fibrillation history. A two-tailed P value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS statistics software (IBM, version 22.0).

Results

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

A total of 922 patients (mean age 78.7 years, 38.8% women) were ultimately enrolled in this study. In-hospital bleeding events were observed in 38 patients (4.1%, bleeding group). The patients with and without in-hospital bleeding were well balanced in terms of most baseline clinical characteristics; however, the incidence of hypertension (63.2% vs.77%, P=0.048) and atrial fibrillation (26.3% vs. 11.3%, P=0.01) was significantly higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group (Table 1). In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed in coronary angiography characteristics between groups.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics.

| Variable | Without bleeding n=884 | With bleeding n=38 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 78 (76–81) | 78 (77–80) | 0.837 |

| Female | 345 (39.0%) | 13 (34.2%) | 0.551 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.1 (20.7–25.1) | 23.3 (19.7–25.1) | 0.607 |

| SBP, mmHg | 134 (118–151) | 122 (110–141) | 0.430 |

| Current smoker | 337 (38.1%) | 10 (26.3%) | 0.141 |

| Hypertension | 681 (77.0%) | 24 (63.2%) | 0.048 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 266 (30.1) | 10 (26.3%) | 0.619 |

| Stroke history | 138 (15.6%) | 7 (18.4%) | 0.641 |

| Atrial fibrillation history | 100 (11.3%) | 10 (26.3%) | 0.010 |

| Gastritis history | 81 (9.2%) | 4 (10.5%) | 0.772 |

| Previous MI | 154 (17.4%) | 10 (26.3%) | 0.160 |

| Previous PCI | 128 (14.5%) | 4 (10.5%) | 0.496 |

| Previous CABG | 15 (1.7%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0.493 |

| Type of ACS | |||

| STEMI | 237 (26.8%) | 15 (39.5%) | 0.083 |

| NSTE-ACS | 647 (73.2%) | 23 (60.5%) | 0.083 |

| Ejection fraction | 55 (48–60) | 54 (46–59) | 0.345 |

| Angiography characteristics | |||

| CAG | 409 (46.3%) | 15 (39.5%) | 0.677 |

| One-vessel disease | 301 (35.1%) | 20 (52.6%) | 0.123 |

| Two-vessel disease | 374 (42.3%) | 7 (18.4%) | 0.313 |

| Multivessel disease | 583 (66.0%) | 18 (47.4%) | 0.208 |

| Left main | 69 (7.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0.353 |

| Left anterior descending | 191 (21.6%) | 9 (23.7) | 0.093 |

| CTO | 224 (25.3%) | 3 (7.9%) | 0.307 |

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS, non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; CTO, chronic total occlusion; CAG, coronary angiography.

Laboratory Measurements

Laboratory measurement data are shown in Table 2. The hemoglobin (P=0.003) and creatinine clearance (P<0.001) values were significantly lower, whereas the leucocyte count (P=0.003), alanine aminotransferase (P=0.002), brain natriuretic peptide (P=0.008) and creatine kinase isoenzyme (P=0.04) values were significantly higher, in patients with than without bleeding.

Laboratory Measurements.

| Variable | Without bleeding n=884 | With bleeding n=38 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 119 (107–130) | 111 (94–119) | 0.003 |

| Platelet count, 103/dL | 178 (142.5–216) | 180 (139–226) | 0.816 |

| Platelet distribution width, fL | 13.6 (12.0–15.4) | 13.3 (11.9–15.0) | 0.430 |

| Leukocyte count, 103/dL | 6.4 (5.3–8.2) | 8.1 (6.0–12.6) | 0.003 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | 65.6 (49.0–86.3) | 43.1 (32.8–65.2) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid, μmmol/L | 360.1 (291.7–428.5) | 348.7 (280.5–444.9) | 0.640 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, u/L | 19.1 (12.5–31.2) | 30.2 (14.6–80.2) | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.808 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 3.8 (3.2–4.4) | 3.8 (3.0–4.3) | 0.481 |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | 2.3 (1.6–2.9) | 0.894 |

| High-density lipoprotein, mmol/L | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.382 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | 1144 (325–3016) | 1963 (717–7693) | 0.008 |

| Creatine kinase isoenzymes, u/L | 13.6 (10.2–21.9) | 19.6 (10.2–55.1) | 0.040 |

In-Hospital Therapy

As shown in Table 3, diuretics (68.4% vs. 46.2%, P=0.007) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs; 97.4% vs. 80.8%, P=0.01) were used significantly more frequently in patients with than without bleeding. A trend toward more frequent use of P2Y12 receptor inhibitors (94.7% vs. 89.4%, P=0.289) and fondaparinux (2.6% vs. 0.3%, P=0.155) was observed in patients with than without bleeding. Use of antiplatelet and anticoagulation (including warfarin, NOACs and fondaparinux) medications was similar between the bleeding and non-bleeding groups.

In-Hospital Therapy.

| Variable | Without bleeding n=884 | With bleeding n=38 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 752 (85.1%) | 29 (76.3%) | 0.142 |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitors | 790 (89.4%) | 36 (94.7%) | 0.289 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 80 (9.0%) | 3 (7.9%) | 1.000 |

| LMWH | 455(51.5%) | 19 (50.0%) | 0.859 |

| Warfarin | 41 (4.6%) | 1(2.6%) | 1.000 |

| INR 2–3 | 41 (26.2%) | 1 (2.4%) | 1.000 |

| NOACs | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| Fondaparinux | 3 (0.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0.155 |

| ACEI or ARB | 555 (62.8%) | 21 (55.3%) | 0.349 |

| β-Blockers | 607 (68.7%) | 22 (57.9%) | 0.163 |

| Statins | 859 (97.5%) | 38 (100.0%) | 0.324 |

| Diuretics | 408 (46.2%) | 26 (68.4%) | 0.007 |

| Positiveinotropic medicines | 133 (15.0%) | 17 (44.7%) | <0.001 |

| Vasoactive drugs | 231 (26.1%) | 15 (39.5%) | 0.069 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 714 (80.8%) | 37 (97.4%) | 0.010 |

| PCI | 252 (28.5%) | 13 (34.2%) | 0.447 |

| In-hospital stay, days | 9 (7–13) | 11 (9–15) | 0.020 |

LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; NOACs, non–vitamin K oral anticoagulants; INR, international normalized ratio; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

No significant difference was observed between groups in terms of PCI treatment. The average hospitalization stay was significantly longer in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group.

In-Hospital Outcomes

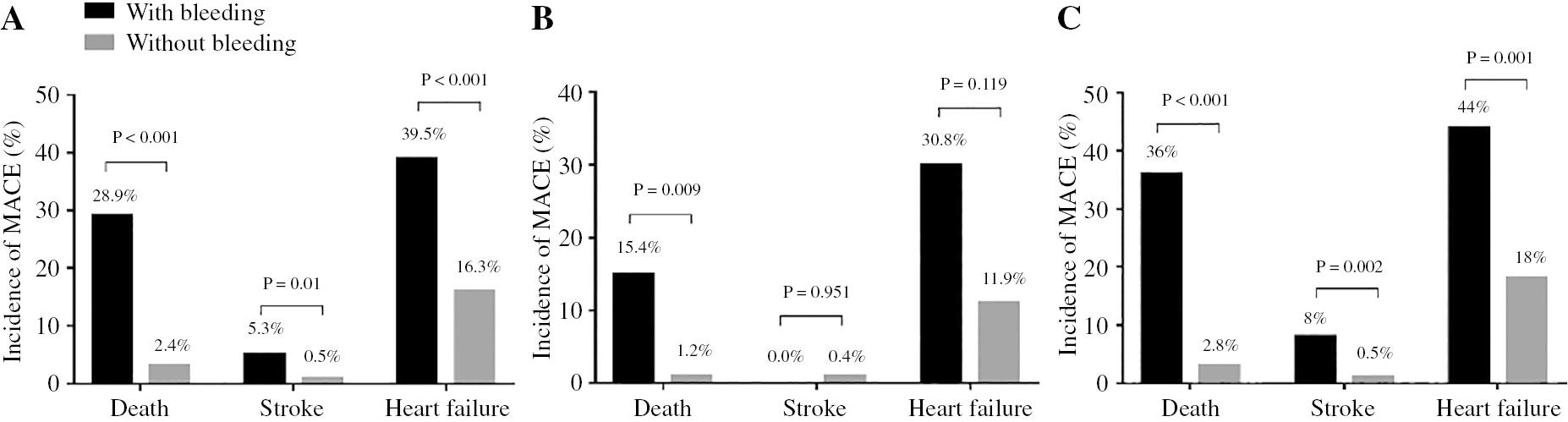

The most common bleeding site in older patients with ACS was the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 2), which accounted for 52.6% of the total bleeding complications; this was followed by dermatomucosal bleeding in six cases, unknown causes of bleeding in five cases, pneogaster bleeding in three cases, genitourinary bleeding in two cases, CNS bleeding in one case and otolaryngology bleeding in one case. The in-hospital mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with than without bleeding (28.9% vs. 2.4%, P<0.001). Furthermore, the prevalence of other in-hospital outcomes including stroke (5.3% vs. 0.5%, P<0.001) and heart failure (39.5% vs. 16.3%, P<0.001) was also significantly higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group. Subgroup analyses indicated that, for patients treated with PCI, although no statistically significant difference in stroke and heart failure events was observed between the bleeding and non-bleeding groups, the in-hospital all-cause mortality rate was significantly higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group. In patients who received conservative medicine treatment, the incidence of in-hospital MACE was also higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group (Figure 3).

Differences in Adverse Events between Groups.

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) during hospitalization. (A) The incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) was higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group. (B) In patients who received PCI treatment, no statistically significant difference was observed in stroke and heart failure events between the bleeding and non-bleeding groups. All-cause mortality during hospitalization was higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group. (C) In patients who received conservative medicine treatment, the incidence of in-hospital MACE was higher in the bleeding group than the non-bleeding group.

Multivariate Analysis

After adjustment for age and sex (model 1, Table 4), hypertension and atrial fibrillation remained clinical risk factors associated with bleeding; moreover, anemia, higher leukocyte count, renal insufficiency, elevated alanine aminotransferase, Ln brain natriuretic peptide and creatine kinase isoenzymes values were laboratory parameters associated with bleeding. Use of diuretics, positive inotropic agents and PPIs remained risk factors for bleeding. After adjustment for age, sex, hypertension and atrial fibrillation (model 2, Table 4), multivariate regression analysis indicated that anemia; renal insufficiency; elevated leukocyte count, alanine aminotransferase, Ln brain natriuretic peptide and creatine kinase isoenzymes; use of diuretics, positive inotropic agents and PPIs; and longer hospitalization were independent risk factors for bleeding complications in patients with ACS older than 75 years during hospitalization (model 2, Table 4). After adjustment for age, sex, hypertension and atrial fibrillation, assessment of all potential variables simultaneously indicated that anemia, elevated leukocyte count, renal insufficiency and PPI use remained independent risk factors for bleeding (model 3, Table 4).

Univariable and Multivariable Binary Logistic Regression Models.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age and sex adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value | Age, sex, and clinical covariate adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value | Age, sex, and clinical covariate adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Clinical covariates | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 0.511 | 0.260–1.006 | 0.052 | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.800 | 1.321–5.936 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Laboratory data | |||||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 0.981 | 0.968–0.994 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Anemia | 3.198 | 1.593–6.422 | 0.001 | 3.144 | 1.557–6.348 | 0.001 | 2.919 | 1.332–6.399 | 0.007 |

| Leukocyte count, 103/dL | 1.166 | 1.080–1.258 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Leukocyte count >10×10³/dL | 4.191 | 2.104–8.350 | <0.001 | 3.821 | 1.892–7.717 | <0.001 | 2.251 | 1.013–5.005 | 0.046 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | |||||||||

| Renal insufficiency, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 | 4.038 | 1.937–8.415 | <0.001 | 4.114 | 1.948–8.685 | <0.001 | 2.668 | 1.175–6.055 | 0.019 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, u/L | 1.003 | 1.001–1.006 | 0.006 | 1.003 | 1.001–1.005 | 0.008 | 1.002 | 1.000–1.005 | 0.058 |

| Ln Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | 1.340 | 1.090–1.647 | 0.006 | 1.273 | 1.028–1.575 | 0.027 | 0.978 | 0.768–1.245 | 0.858 |

| Creatine kinase isoenzymes, u/L | 1.002 | 1.001–1.004 | 0.001 | 1.002 | 1.001–1.004 | 0.001 | 1.002 | 1.000–1.003 | 0.029 |

| In-hospital therapy | |||||||||

| Diuretics | 2.528 | 1.259–5.073 | 0.009 | 2.231 | 1.095–4.544 | 0.027 | 1.305 | 0.587–2.902 | 0.514 |

| Positive inotropic medicines | 4.571 | 2.350–8.893 | <0.001 | 3.956 | 1.966–7.963 | <0.001 | 2.997 | 1.361–6.598 | 0.006 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 8.810 | 1.200–64.660 | 0.032 | 8.799 | 1.194–64.823 | 0.033 | 7.140 | 0.962–52.983 | 0.055 |

| In-hospital stay, days | 1.018 | 0.999–1.038 | 0.058 | 1.019 | 1.001–1.038 | 0.042 | 1.009 | 0.990–1.029 | 0.366 |

Discussion

The main findings of the present analysis are as follows: (1) in patients with ACS older than 75 years, the incidence of in-hospital bleeding events was approximately 4.1% in a real-world scenario; (2) independent risk factors for in-hospital bleeding included anemia, renal insufficiency, elevated leukocyte count and use of positive inotropic medicines; and (3) in-hospital bleeding was strongly associated with MACE during hospitalization.

Previous studies have reported that the incidence of bleeding events in patients with ACS fluctuates between 1.8% and 15.4% [5–9, 18, 19]. Because of differences in the definitions of bleeding events, sample sizes, study regions and study participants, large differences in the incidence of bleeding outcomes in patients with ACS have been reported. Recently, Zhao et al. [20] have analyzed 5887 patients in the CCC-ACS project, which was designed to assess the clinical effectiveness and safety of dual loading antiplatelet therapy for patients 75 years or older undergoing PCI for ACS. In that study, the incidence of bleeding events during hospitalization was 6.8%. In our study, the incidence of bleeding events was 4.1%, in agreement with the above studies. The NCDR Cath PCI trial has reported a rate of 57.9% for non-access site hemorrhage, with gastrointestinal hemorrhage accounting for 16.6% of the cases [7].

In our study, 52.6% patients suffered gastrointestinal bleeding, despite prophylactic use of PPIs during hospitalization in 81.5% of patients. The gastrointestinal bleeding in this patient cohort in the presence of PPIs might potentially have been due to more vulnerable gastrointestinal mucosa, Helicobacter pylori infection, or interactions between PPI and clopidogrel. Pharmacological studies have confirmed that different PPIs have different effects on the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel, but no clinical evidence has indicated their effects on clinical prognosis.

Previous studies have suggested that the risk factors for bleeding in patients with ACS include age, female sex, prior PCI, renal insufficiency, hemodialysis, STEMI, non-STEMI and diabetes mellitus [5, 21, 22]. Our results are largely consistent with those of prior studies, indicating associations among anemia, renal insufficiency, use of positive inotropic medicines and bleeding risk. Anemia, the most common physical condition in older patients, has a reported incidence as high as 24–40% in hospitalized older patients (>65 years of age) [23]. In a meta-analysis of 240,000 patients, the risks of long-term death, heart failure, cardiogenic shock and bleeding have been found to be significantly higher in patients with ACS with anemia than in non-anemic patients [24]. Kidney function is well known to decrease with age. The TRILOGY ACS trial has demonstrated that the incidence of hemorrhagic and ischemic events increases with the worsening of chronic kidney disease, and damaged kidneys may result in a low response to antiplatelet therapy in patients with ACS with chronic kidney disease [25]. The kidneys not only are excretory organs but also have endocrine functions [26]. With the progression of renal failure, anemia eventually occurs, and in older patients with ACS, the interaction between renal failure and anemia promotes the occurrence of hemorrhage events. Therefore, for high-risk patients, actively correcting the anemia and administering drugs at carefully considered, appropriate dosages and time courses according to the glomerular filtration rate is clinically important. The use of positive inotropic drugs during hospitalization suggests that the patient is in a state of chronic heart failure. Our study demonstrated that heart failure is a risk factor for bleeding in patients with ACS.

In addition to the above common risk factors, elevated leukocyte count is an independent risk factor for in-hospital bleeding in older patients with ACS. Although previous studies have shown that leukocyte count is an independent risk factor for MACE in patients with ACS, the prognostic role of leukocytes in bleeding events remains unclear. Over the past decade, researchers have focused on the relationship between leukocyte count and prognosis in patients with ACS. Ndrepepa et al. [27] have analyzed 4329 patients with ACS treated with PCI and found an association between elevated leukocyte count and higher rates of 30-day mortality, major bleeding and stroke. The Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy trial [28] has also established a strong correlation between leukocyte count and bleeding events. In the present study, we provide the first clarification of the relationship between leukocyte counts and in-hospital bleeding in older patients with ACS. Although the mechanism underlying this relationship is not very clear, we speculate that enhanced inflammatory reactions may directly damage the gastric mucosal barrier, and local short-term or prolonged hypoxia due to low cardiac output in patients with ACS might also aggravate gastric damage by releasing inflammatory mediators; moreover, enhanced inflammatory reactions might cause clotting function disorders.

The present study demonstrated a strong association between the occurrence of bleeding and MACE, particularly all-cause mortality. Similar results were found in subgroup analyses including patients treated with either PCI or conservative medications. The mechanisms of underlying the increased mortality associated with bleeding events are currently believed to include hypotension shock, inflammatory reactions caused by anemia and blood transfusion, and stent thrombosis caused by discontinuation of antiplatelet drugs due to bleeding [29]. Previous studies have suggested that in-hospital bleeding is associated with short-, moderate- and long-term mortality in patients with ACS, especially the first month after ACS [7, 8, 29]. A meta-analysis of 2.4 million patients has indicated that non-access site and access site bleeding increase the risk of perioperative death by 4 and 1.7 times, respectively. The risk of death increases by 3, 6 and 23 fold with gastrointestinal bleeding, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, and intracranial hemorrhage, respectively [30]. In the Dynamic Registry trial [31] in 17,378 patients, 1019 (5.9%) patients experienced bleeding, and 369 (2.1%) died during hospitalization after PCI. Age is an independent determinant of death in patients with ACS, and the incidence of bleeding and in-hospital mortality increase monotonically with increasing age. As recently reported, vascular complications are not associated with an increased risk of death except in the presence of severe bleeding [32].

Study Limitations

The advantage of this study is the presentation of objective real-world evidence of bleeding events in patients with ACS above 75 years of age during hospitalization. However, this single-center, retrospective study has several limitations. First, this study analyzed only in-hospital outcomes but did not assess the relationships between bleeding events and long-term adverse outcomes in older patients with ACS. Second, the results of this study suggested that the most common bleeding site is the gastrointestinal tract. However, we did not conduct gastroscopy and Helicobacter pylori examination for all these patients to assess pathological data in these patients.

Conclusion

In this real-world study, the incidence of in-hospital bleeding events in patients above 75 years of age with ACS was approximately 4.1%. Independent risk factors for in-hospital bleeding events included anemia, renal insufficiency, elevated leukocyte count and positive inotropic agents. Bleeding events were strongly associated with MACE during hospitalization. Therefore, for patients above 75 years of age with ACS, physicians should not only focus on coronary ischemic events but also undertake procedures to avoid bleeding events to the greatest extent possible.