Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in elderly adults and its prevalence increases with age [1, 2]. One of the most important complications associated with AF is ischemic strokes, and AF-related stroke is more likely to result in disability, dementia, and death [3]. While oral anticoagulants (OACs) significantly reduce the risk of stroke, challenges remain in appropriate risk assessment, treatment adherence, and guideline-adherent prescribing [4, 5]. Of note, up to half of elderly adults with AF do not receive anticoagulant therapy because of its perceived side effects, but such nonprescribing leads to more adverse outcomes [6–8].

Frailty is defined as a state of vulnerability to adverse outcomes from stressors [9]. The prevalence and clinical significance of frailty increase with aging [10, 11]. Frailty is a strong independent predictor of cardiovascular-related death and is also associated with pathophysiological factors in the development of cardiovascular diseases and thrombosis [12]. The prevalence of frailty in elderly adults with cardiovascular diseases is reported to be three times higher than in those without cardiovascular diseases [13]. However, data on the prevalence of frailty in elderly adults with AF are limited, especially from Asian countries. Moreover, the findings of studies on the prevalence of anticoagulant prescription according to frailty status are not consistent [14]. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of frailty in elderly adults with AF, factors associated with frailty status, and the prevalence of OAC therapy in frail and nonfrail patients in this population.

Methods

Study Population

We consecutively selected 500 nonvalvular AF patients aged 65 years or older who were enrolled in the Chinese Atrial Fibrillation Registry (CAFR) study between April 2017 and December 2017. The CAFR study is a prospective, multicenter registry study that enrolled AF patients from hospital wards and outpatient clinics. All enrolled patients had AF documented by either ECG or Holter monitoring within the previous 6 months. Patients with transient and reversible AF, patients with diagnosed rheumatic heart disease, and patients who had undergone a left atrial appendage closure procedure were excluded from the present study. Data on the patients’ demographic characteristics, medical histories, and treatments received were collected by face-to-face interview and medical record review at enrollment. Each patient was followed up by telephone every 6 months, and data on treatment and clinical outcomes were collected. All of the study patients were ambulatory when the current study was conducted. The CAFR study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital. All patients signed consent forms. For the present study, we obtained separate ethics approval from the same hospital and obtained oral consent of the patients for the extra questions being asked.

Measurements

Measured factors included demographic characteristics, chronic comorbidities, which includes: congestive heart failure (CHF), hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, hyperlipidemia, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), vascular disease, major bleeding (International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria: fatal bleeding, and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular, or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL or more or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells [15]), chronic renal disease (dialysis, transplant, or creatinine level greater than 2.26 mg/dL), and chronic liver disease (cirrhosis or bilirubin level more than two times the upper normal limit with glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase/glutamic pyruvic transaminase/alkaline phosphatase level more than three times the upper normal limit). The definitions of chronic renal disease and chronic liver disease are consistent with the definitions used in the HAS-BLED scoring system. Data on other factors, including type of AF (paroxysmal or persistent), history of catheter ablation procedure(s), CHA2DS2-VASc score (1 point when a patient has a history of CHF, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or vascular disease, is 65 years or older, or is female, and 2 points if a patient is 75 years or older or has a history of stroke/TIA [16]), modified HAS-BLED score without labile international normalized ratio (1 point when a patient has a history of hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, or bleeding tendency/predisposition, is elderly [>65 years old], and uses drugs/alcohol concomitantly [17]), the use of anticoagulants (warfarin and non-vitamin K antagonist OACs), and the number of concomitant medications (including antiarrhythmic drugs, rate control drugs, antiplatelet drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, and hypoglycemic agents) were also collected. Then we evaluated the patient’s frailty status by telephone follow-up.

Frailty Status

The Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale (CSHA-CFS) [18] was used to measure frailty. It assesses factors such as complications, cognitive function, and disability comprehensively (Supplementary Figure S1). The CSHA-CFS score has been widely used to evaluate frailty status worldwide and to predict adverse outcomes such as death and hospitalization [19–22]. A recently published article reported that the CSHA-CFS has the highest sensitivity and specificity with the lowest misclassification rate among the screening tools for patients with heart failure [23]. A translated telephone version of the CSHA-CFS [24] (Supplementary Figure S1) was administered by two trained investigators (LJP and LMM) through telephone interview. The instructions for use of the CSHA-CFS w strictly followed when the interview was conducted and the CSHA-CFS score was assigned. The CSHA-CFS provides an estimation of frailty on a scale ranging from 1 to 7 based on the patient’s functional autonomy status, mobility, and need for assistance with activities of daily living. Patients were categorized into a nonfrail group (CSHA-CFS score less than 5) and a frail group (CSHA-CFS score 5 or greater) on the basis of their CSHA-CFS score.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population were summarized by descriptive analysis. Continuous variables are reported as the mean and the standard deviation or the median and the interquartile range and were compared by ANOVA. The categorical variables are expressed as a percentage and were compared by a chi-square test. We described the prevalence of frailty according to age, sex, and CHA2DS2-VASc score. Differences in the prevalence of frailty between male and female sex were tested by the chi-squared test; differences in the prevalence of frailty in different age groups and CHA2DS2-VASc score groups were tested by the Mantel-Haenszel test.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the factors associated with frailty status. Factors including age (as a continuous variable), sex, previous or current smoking/alcohol drinking, history of CHF, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, hyperlipidemia, stroke/TIA, major bleeding, chronic liver disease, chronic renal disease, catheter ablation procedure, and type of AF were adjusted. The variables mentioned were selected to include all measured clinical variables of known or suspected factors for the frailty status.

Results

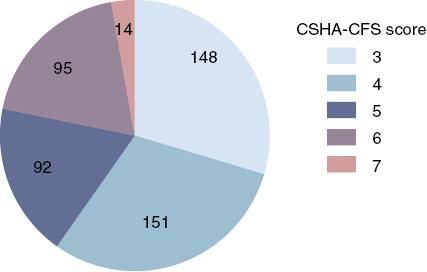

Of the 500 patients studied, 148 patients (29.6%), 151 patients (30.2%), 92 patients (18.4%), 95 patients (19.0%), and 14 patients (2.8%) were scored 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively (Figure 1), and 201 patients (40.2%) were categorized as frail (CSHA-CFS score 5 or greater). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in the frail and nonfrail groups. A higher proportion of frail patients were female (P=0.002), had persistent AF (P=0.009), and had CHF (P<0.001). Frail patients were about 5 years older than nonfrail patients (P<0.001), had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores (P<0.001), and were taking more concomitant medications (P<0.001), while they were less likely to have received catheter ablation (P=0.026).

Distribution of Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale (CSHA-CFS) Scores.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Overall (n=500) | Not frail (CSHA-CFS score <5) (n=299) | Frail (CSHA-CFS score ≥5) (n=201) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 75.2 (6.7) | 73.3 (5.9) | 78.1 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 258 (51.6) | 137 (45.8) | 121 (60.2) | 0.002 |

| CHF, n (%) | 87 (17.4) | 30 (10.0) | 57 (28.4) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 362 (72.4) | 218 (72.9) | 144 (71.6) | 0.76 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 140 (28.0) | 80 (26.8) | 60 (29.9) | 0.45 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 99 (19.8) | 53 (17.7) | 46 (22.9) | 0.16 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 148 (29.6) | 86 (28.8) | 62 (30.8) | 0.62 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 219 (43.8) | 132 (44.1) | 87 (43.3) | 0.85 |

| Major bleeding*, n (%) | 27 (5.4) | 12 (4.0) | 15 (7.5) | 0.09 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 109 (2) | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 0.05 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 11 (2.2) | 4 (1.3) | 7 (3.5) | 0.11 |

| Previous or current smoking and drinking, n (%) | 151 (30.2) | 95 (31.8) | 56 (27.9) | 0.35 |

| Type of AF, n (%) | ||||

| Paroxysmal | 232 (46.4) | 153 (51.2) | 79 (39.3) | 0.009 |

| Persistent | 268 (53.6) | 146 (48.8) | 122 (60.7) | |

| History of catheter ablation procedure, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 403 (80.6) | 229 (76.6) | 174 (86.6) | 0.026 |

| ≥1 | 97 (19.4) | 70 (23.4) | 27 (13.4) | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, median (IQR) | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

| Modified HAS-BLED score†, median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.29 |

| Number of concomitant medications, mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.4 (1.6) | <0.001 |

AF, Atrial fibrillation; CHF, congestive heart failure; CSHA-CFS, Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

*According to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis definition of major bleeding: fatal bleeding, and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL or more or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells.

†Labile international normalized ratio was not used in calculating the HAS-BLED score.

Prevalence of Frailty in Patients Aged 65 Years or Older with AF

The prevalence of frailty increased from 22.5% in the patients aged 65–69 years to 84.6% in the patients aged 85 years or older (Figure 2A; P for trend less than 0.001). A higher proportion of female patients (46.9%) were frail compared with male patients (33.1%; Figure 2B; P=0.002). The proportion of the frail patients increased from 31.3 to 59.7% as the CHA2DS2-VASc score increased from 1 to 6 or greater (Figure 2C; P for trend less than 0.001).

Factors Associated with Frailty

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, a history of CHF was the strongest factor associated with frailty (odds ratio [OR] 2.40, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.39–4.14, P=0.002). Female sex (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.27–3.43, P=0.004) and advanced age (OR 1.13 for every year older, 95% CI 1.09–1.17, P<0.001) were also significantly associated with frailty status (Table 2).

Multivariable Logistic Analysis of Factors Associated with Frailty Status in Elderly Adult Patients with Atrial Fibrillation.

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.13 | 1.09–1.17 | <0.001 |

| Female | 2.09 | 1.27–3.43 | 0.004 |

| CHF | 2.40 | 1.39–4.14 | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 0.66 | 0.41–1.05 | 0.08 |

| Diabetes | 1.09 | 0.70–1.71 | 0.70 |

| Stroke/TIA | 1.29 | 0.78–2.13 | 0.32 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.91 | 0.59–1.42 | 0.69 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.02 | 0.68–1.55 | 0.92 |

| Major bleeding* | 2.22 | 0.93–5.32 | 0.07 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3.25 | 0.72–14.6 | 0.13 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.12 | 0.49–9.29 | 0.32 |

| Previous or current smoking and drinking | 1.36 | 0.79–2.35 | 0.26 |

| Type of atrial fibrillation | 1.31 | 0.85–2.02 | 0.23 |

| History of catheter ablation procedure | 0.97 | 0.55–1.74 | 0.93 |

Factors included in multivariate logistic regression analysis are all listed.

CHF, Congestive heart failure; CI, confidence index; OR, odds ratio; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

*According to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis definition of major bleeding: fatal bleeding, and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL or more or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells.

Relationship between Frailty and OAC Therapy

Among the 463 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or greater, there was no significant difference in the proportion receiving anticoagulant therapy between the frail group and the nonfrail group (38.2 vs. 42.2%, P=0.38). In the frail group, warfarin was used in 29.3% of the patients and non-vitamin K antagonist OACs (dabigatran and rivaroxaban) were used in 8.9% of the patients. In the nonfrail group, the corresponding proportions were 33.2 and 9.0%. Never having been prescribed anticoagulants in frail patients (81.7%), rather than withdrawal of therapy (18.3%), was more likely to be the reason why frail patients were not treated with an anticoagulant.

Discussion

Our principal findings in this analysis are as follows: (1) the prevalence of frailty was about 40% among AF patients with a mean age of 75 years; (2) advanced age, female sex, and a history of heart failure were associated with frailty; (3) the rate of use of an anticoagulant was about 40% in this population. Lacking OAC prescription was the main reason for no OAC treatment in frail patients.

Prevalence of Frailty in AF Patients and Factors Associated with Frailty

The present study shows that frailty was much more prevalent among AF patients compared with other common diseases and would therefore have a great impact on patients’ daily lives. For example, a systematic review including 21 community-based studies showed that the prevalence of frailty was 15.7% for participants aged 80–84 years and 26.1% for participants aged 85 years or older [25]. Compared with other chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, frailty status was at least twofold more common in AF patients. Although our study included younger participants, the prevalence of frailty status was 40%, compared with 15% in Chinese diabetic patients aged between 74 and 84 years [26]. A systematic review and meta-analysis found the weighted mean prevalence of frailty in patients with AF was 39% (95% CI 36–42%), similar to findings in the present study [27].

We also found that CHF was associated with a 2.4-fold higher risk of being frail in elderly adults with AF. Coexisting AF and CHF may make patients more likely to suffer from cognitive impairment, slowing gait speed, and disability [28]. Moreover, comorbid AF and CHF leads to worse prognosis compared with each condition individually [29, 30]. Therefore, this group of AF patients should optimize their routine heart failure treatment, get proper anticoagulant therapy, and may even consider ablation therapy to improve outcomes and quality of life [31].

Frailty Status and OAC Therapy

Published data are inconsistent as to whether frailty has any impact on anticoagulant therapy use even though this has been widely studied [32, 33]. Because of the complex impact of frailty on multiple systems, optimizing anticoagulant therapy for frail patients with AF is presently challenging. We found that nonprescribing rather than withdrawal of therapy was the main reason for lack of OAC treatment in frail patients. Frail patients concomitantly used more medications in our study, which may negatively affect providers’ prescription of OAC. Prior studies demonstrated that providers had major concerns as to the potential side effects of bleeding when prescribing anticoagulants [34, 35]. Nevertheless, many studies have found that the probability of major bleeding in elderly patients receiving anticoagulant therapy was not higher than in the overall population [36–38]. One study found the net clinical benefits of treating patients with OACs increased monotonically with age [39]. A greater understanding of the implications of frailty for the net benefit of anticoagulation will be important for health care providers to facilitate holistic clinical decision-making. Discontinuation was another reason for undertreatment with OACs in frail elderly patients. Our data suggested about 20% of frail patients had ever been treated with OACs but the OACs treatment was later discontinued. One other study reported that at follow up at 4 years, 53 of 73 frail elderly patients (72.6%) had discontinued OAC therapy [40]. Optimizing follow-up actions for frail AF patients receiving anticoagulant therapy, patient education, and consideration of patient values may help to minimize the side effects of anticoagulant therapy [41, 42].

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, most participants were from Beijing, so the conclusions may not be generalizable to a broader population. As a cross-sectional study, there were no follow-up data demonstrating the relationship between frailty, anticoagulation, and adverse outcomes. Finally, this study used a single method (CSHA-CFS) to assess the frailty status, mainly based on the evaluation of dysfunction, and could not fully reflect the decline of physiological function, which may limit the accuracy of distinguishing nonfrail elderly patients from disabled patients [43].