1. INTRODUCTION

Long COVID, a complex condition characterized by enduring and diverse symptoms, is defined as continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection. These symptoms persist for at least 2 months, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1] and negatively affects the quality of life. According to the WHO, 10%–20% of patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 develop long COVID globally [1]. Long COVID symptoms and signs include cardiopulmonary issues (fatigue, palpitations, and chest pain), naso-oropharyngeal conditions (anosmia, dysgeusia, and cough), gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort), musculoskeletal problems (arthralgia, myalgia, and impaired mobility), neuropsychologic conditions (memory loss, depression, and anxiety), miscellaneous issues (fever, headache, and skin rash), and systemic conditions (weakness and general malaise) [2, 3].

Long COVID is believed to have a pathophysiologic basis, but is not well understood. Multiple studies have revealed that the mechanism underlying long COVID includes viral and antigen persistence [4, 5]. SARS-CoV-2 evades immune responses, especially in immunocompromised individuals, which prolongs the infection. This persistence involves continuous viral replication and the presence of virus molecules, leading to unique immune reactions compared to an acute infection. Some SARS-CoV-2 antigens non-specifically activate T cells, resulting in excessive immune activation that impairs viral clearance and sustains viral presence [6]. Multiple reports have indicated that inflammation has a pivotal role in long COVID symptoms. The intense interaction between the virus receptor-binding domain and human angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptors initiates inflammatory cascades, resulting in the release of numerous proinflammatory cytokines [7]. The most persistent and prominent cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, C-reactive protein, interleukin-1beta, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha [8, 9].

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the WHO, and the National Institutes of Health offer insights into treatment and management approaches for patients with long COVID. However, these guidelines lack detailed treatment recommendations. Approaches often stem from small-scale studies or successful interventions in patients with similar conditions. For example, pharmacologic treatments effective for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, such as low-dose naltrexone, β-blockers, and alpha-adrenergic agonists, show promise in relieving post-COVID fatigue [10, 11]. Non-pharmacologic methods like cognitive pacing may improve cognitive dysfunction and fatigue caused by COVID-19 [12]. Moreover, some pilot studies have suggested that probiotics alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms [13], while transcutaneous vagal stimulation may mitigate autonomic dysfunction caused by COVID-19 [14]. Taken together, current clinical research targeting long COVID symptoms is limited with most treatments primarily addressing individual symptoms rather than multiple symptoms caused by COVID-19.

Cs4 is fermented by the herbal medicine, Cordyceps sinensis (Berk) Sacc. Previous studies have shown that Cs4 has anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, antiviral, and antifungal effects [15–17]. For example, an in vivo study showed that Cs4 treatment alleviated nasal symptoms in ovalbumin-sensitized and challenged mice by inhibiting the expression of IL-4 and IL-13 in nasal fluid, as well as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in lung tissue [15]. Additionally, Cs4 treatment reduced IgE levels and inflammatory cell counts, including eosinophils, in the bronchoalveolar fluid of capsaicin-challenged rats [15]. Cs4 may have potential efficacy against long COVID symptoms based on the pharmacologic mechanisms of action but there is a lack of clinical trial evidence.

The efficacy and safety of Cs4 in alleviating long COVID symptoms were investigated in the current study. We hypothesized that treatment with Cs4 alleviate some long COVID symptoms.

2. METHODS

2.1 Study design

This was a randomized, 24-week, waitlist-controlled trial. Participants with long COVID symptoms were randomly assigned to the Cs4 or waitlist control group. Cs4 placebo could not be blinded due the unique color and smell, therefore the waitlist control group received Cs4 after the first waiting period. The primary outcome was the change in the symptom severity dimension of the self-declared modified COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRSm) from baseline to 12 weeks. This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster [HKU/HA HKW IRB] (No. UW 23-011). The protocol was registered at ClinicalTrial.gov (No. NCT06054438).

2.2 Participants

The trial was conducted at the Specialist Clinical Centre for Teaching and Research (Sassoon Road, School of Chinese Medicine, the HKU). Participants were recruited through a combination of advertisements and the webpage of the School of Chinese Medicine at HKU. Before scheduling an onsite visit involving clinical examinations following a standardized protocol, prescreening was conducted via telephone. All participants provided written informed consent.

Eligible individuals were between 18 and 75 years of age and had previously been diagnosed with COVID-19. The participants must have experienced at least one long COVID symptom lasting for at least 2 months after the SARS-CoV-2 infection and the self-reported post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) scale score must be >1. The PCFS, developed by Klok and colleagues, is a scale intended for patients to assess the impact of COVID-19 on functional status. The PCFS spans from grade 0, indicating “no functional limitations,” to grade 4 “severe functional limitations” [18]. Confirmation of a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection must be provided by an Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) or rapid antigen test with documentation from the local health authority. Additionally, eligible individuals should not currently be taking any orally administered Chinese medicine. Individuals were excluded if allergic to C. sinensis, were pregnant or breastfeeding, had impaired hepatic or renal function, were unable to read and/or write Chinese or English, or were unable to communicate (e.g., due to cognitive impairment).

During the patient screening, two investigators assessed the eligibility of individuals based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participant demographics, including gender, age, height, and weight, as well as the date of the most recent COVID-19 infection, number of COVID-19 vaccine doses, and pre-existing morbidities, were recorded by the investigators. Laboratory testing for complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), thyroid function, liver function, and renal function was also performed.

2.3 Patient and public involvement

Before the trial began, formative research used qualitative methods, including in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, to assess the feasibility and acceptability of Cs4 for treating post-COVID-19 symptoms. This study followed a participatory research design with researchers and registered traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Hong Kong contributing to the research design from the proposal preparation stage. The study findings were disseminated through seminars, online forums, and conferences held locally, nationally, and internationally. The participants in the study were informed that the survey data would be used for research purposes.

2.4 Randomization and blinding

Participants were randomly assigned into two groups (Cs4 and waitlist control groups) at a 1:1 ratio. Randomization with a block size of 10 was performed using a computer-based Excel random number generator. The assignment concealment was achieved by opaque, sealed envelopes. After the study coordinator confirmed the eligibility and obtained consent from the patients, the corresponding envelope was opened. The investigators who screened patients and assessed the outcomes were blinded to the assignments.

2.5 Procedures

The patients in the Cs4 group received Cs4 (0.4 g/capsule, 4 capsules per day [1.6 g daily]) for 12 consecutive weeks and one follow-up evaluation at week 24. Participants in the waitlist control group did not receive Cs4 at week 0, rather were administered Cs4 beginning at week 12 and continuing for 12 consecutive weeks. Cs4 was manufactured by Chinese Pharm (Hong Kong, China) with good manufacturing practice (GMP). To ensure that Cs4 had stable ingredient content, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on multiple batches of Cs4 and demonstrated similarity >96% (the detailed protocol and HPLC results are provided in the Supplement 1).

2.6 Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in the symptom severity dimension of the English version of the modified COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale [C19-YRSm] (range, 0–78 with higher scores indicating greater impact of symptoms) at 12 weeks. C19-YRSm is recommended in the NHS England Clinical Guidance and NICE rapid guidelines [19, 20]. C19-YRSm is the first validated scale describing and grading the severity of long COVID symptoms and functional disability. The scale is comprised of the following 4 subscales: symptom severity, functional ability (range, 0–15 with higher scores indicating a greater impact of symptoms); other symptoms (range, 0–25 with a higher score indicating a greater number of additional symptoms); and overall health (a visual analog scale ranging from 0–10, where higher scores indicated a better health status) [21]. The symptom severity subscale was utilized because this subscale allowed for a comprehensive assessment and quantification of the severity of various long COVID symptoms experienced by participants. The C19-YRSm includes the following symptoms in the symptom severity subscale: breathlessness; cough/throat sensitivity/voice change; fatigue; smell/taste; pain/discomfort; cognition; palpitations/dizziness; post-exertional malaise; anxiety/mood; and sleep. Each item was scored on a scale from 0–3 to indicate severity.

The secondary outcomes included changes in the Brief Fatigue Inventory Form [BFI] (range, 0–90 with higher scores indicating greater severity of fatigue) [22], the Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] (range, 0–21 with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality) [23], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] (range, 0–21 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms) [24], the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), which consists of 4 subscales (symptoms, activity, impact, and total score [range, 0–100 with higher scores indicating greater respiratory severity]) [25], summary scores for the physical and mental components of the Short Form 12 (SF-12) health survey (range, 0–100 with higher scores indicating better health status) [26].

All adverse events were monitored and documented by the investigators. The following laboratory chemistry tests were measured in the blood samples at 12 and 24 weeks: aspartate aminotransferase (AST); alanine aminotransferase (ALT); creatine kinase; creatinine; and urea. When severe adverse events linked to the study intervention occurred, the Trial Steering Committee had the right to terminate the trial prematurely based on the recommendation of the independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Cs4 reduced the symptom severity dimension of the C19-YRSm by 0.8 points based on the results of our pilot study with a Cs4 intervention duration of 2 weeks. In consideration of the likelihood that participants with long COVID symptoms may pursue other medication treatments, the dropout rate was set at 35%. With a standard deviation (σ) of 1.195, a significance level of 5%, and a power of 80%, the sample size was calculated using the following formula [27]: n = [(Zα/2 + Zβ)2 × {2(ó)2}]/(μ1–μ2)2, where n represented the required sample size in each group, μ1 denoted the mean change in symptom severity score from baseline to week 12 by taking Cs4, while μ2 indicated the mean change in symptom severity score from baseline to week 12 without taking Cs4. The clinically significant difference between these mean changes, denoted by μ1–μ2, was established as 0.8, where the assumption was a 0.8-point decrease for the Cs4 group and a 0-point decrease for the waitlist control group. Zα/2 represents the significance level-dependent value (set at 1.96 for a 5% significance level) and Zβ denotes the power-dependent value (with a value of 0.84 for 80% power). According to the formula provided, the sample size needed per group was calculated to be 55, accounting for a dropout rate of 35%. Consequently, the total sample size required for both groups was 110 subjects. This sample size estimation was based on pilot data generated from a 2-week Cs4 treatment, which was different from the treatment duration of this trial (12 weeks). Therefore, we calculated the exact power based on the results of this trial for the primary outcome to ensure that we had sufficient power to derive a confirmative conclusion.

All efficacy and safety analyses were conducted based on the intention-to-treat principle. Missing values were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. Between-group differences in outcomes at 0 and 12 weeks were compared using generalized linear regression models adjusted for potential confounding factors. Additionally, potential interactions between Cs4 treatment and potential effect modifiers were examined, including gender, body mass index (BMI), doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, duration from last infection, and ESR. Statistical significance was determined by a two-sided P < 0.05. Results are reported as between-group differences along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

To address missing data, multiple imputation was used to handle missing data by generating five plausible datasets, analyzing the datasets independently, and combining the outcomes. Additionally, inverse probability weighting was implemented by assigning weights to complete cases based on the inverse of the likelihood of being complete and helping to maintain an unbiased analysis.

3. RESULTS

A total of 151 potential participants were screened for eligibility between April 2023 and June 2023. Among these long COVID participants, 41 did not meet the criteria, leaving a total of 110 participants included in this trial. The trial profile and flow of patient recruitment are shown in Figure 1 . The proportion of the participants who completed a follow-up evaluation at 12 weeks was 92.7% (51/55) in the Cs4 group and 89.1% (49/55) in the waitlist control group. The proportion of participants who completed the follow-up evaluation at 24 weeks was 83.6% (46/55) in the Cs4 group and 72.7% (40/55) in the waitlist control group.

Trial profile and patient flow chart.

Cs4 is the intervention drug Cordyceps sinensis mycelium culture extract.

The baseline characteristics, including age, gender, BMI, morbidities, and blood tests, were well-balanced between the Cs4 and waitlist control groups ( Table 1 ). At baseline, long COVID participants had a median symptom duration of 5 months (IQR, 2–9 months) since the last COVID-19 infection. Of the participants, 10.9%, 66.4%, 20.0%, and 1.8% received 2, 3, 4, and 5 doses of COVID-19 vaccines, respectively. The long COVID participants included in this trial presented with a mean 23.2 (SD, 12.3) long COVID symptom severity assessed by the C19-YRSm.

Baseline characteristics of long COVID participants included in this trial.

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 110) | Cs4 group (n = 55) | Waitlist control group (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median [Q1, Q3] | 37.0 [27.2, 55.0] | 36.0 [28.0, 52.0] | 37.0 [25.5, 59.5] |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 69 (62.7) | 34 (61.8) | 35 (63.6) |

| Male | 41 (37.3) | 21 (38.2) | 20 (36.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median [Q1, Q3] | 22.0 [19.9, 24.3] | 22.3 [19.8, 25.0] | 21.9 [20.1, 24.0] |

| Doses of COVID-19 vaccine received, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | |

| 2 | 12 (10.9) | 7 (12.7) | 5 (9.1) |

| 3 | 73 (66.4) | 36 (65.5) | 37 (67.3) |

| 4 | 22 (20.0) | 9 (16.4) | 13 (23.6) |

| 5 | 2 (1.8) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Symptom duration (months), median [Q1, Q3] | 5.0 [2.0, 9.0] | 5.0 [2.5, 8.0] | 5.0 [2.0, 10.0] |

| Pre-existing morbidities, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 (8.2) | 5 (9.1) | 4 (7.3) |

| Hypertension | 7 (6.4) | 3 (5.5) | 4 (7.3) |

| Respiratory disease | 4 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| Malignancy | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| Immune system disorder | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| PCFS score, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 109 (99.1) | 55 (100) | 54 (98.2) |

| 3 | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) |

| C19-YRSm (symptom severity) scores (range, 0–78), mean (SD) | 23.2 (12.3) | 24.1 (12.5) | 22.3 (12.2) |

| BFI scores (range, 0–90) | 46.5 (15.8) | 46.6 (15.1) | 46.4 (16.6) |

| ISI scores (range, 0–28), mean (SD) | 15.7 (5.0) | 15.6 (4.9) | 15.8 (5.2) |

| HADS scores (subscale range, 0–21), mean (SD) | |||

| Depression | 7.6 (3.7) | 7.0 (3.8) | 8.3 (3.5) |

| Anxiety | 8.1 (3.6) | 7.8 (3.6) | 8.5 (3.7) |

| SGRQ scores (subscale range, 0–100), mean (SD) | |||

| Symptoms | 36.8 (16.0) | 38.8 (17.0) | 34.8 (15.0) |

| Activity | 35.2 (21.8) | 37.9 (20.4) | 32.4 (23.2) |

| Impacts | 30.0 (16.9) | 30.8 (18.8) | 29.1 (15.0) |

| Total score | 32.6 (15.7) | 34.0 (16.5) | 31.1 (14.9) |

| SF-12 scores, mean (SD) | |||

| Physical score | 39.9 (7.9) | 38.2 (7.6) | 41.6 (7.8) |

| Mental score | 39.9 (9.0) | 38.8 (8.9) | 41.0 (9.0) |

| Long COVID symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Fatigue | 105 (95.4) | 54 (98.2) | 51 (92.7) |

| Insomnia | 88 (80) | 45 (81.8) | 43 (78.2) |

| Respiratory symptoms | 62 (56.4) | 32 (58.2) | 30 (54.5) |

| Emotional change | 76 (69.1) | 40 (72.7) | 36 (0.65) |

| WBC (109/L), mean (SD) | 6.1 (1.6) | 6.2 (1.7) | 5.9 (1.5) |

| RBC (1012/L), mean (SD) | 4.7 (0.6) | 4.8 (0.7) | 4.7 (0.6) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), mean (SD) | 13.4 (1.4) | 13.6 (1.1) | 13.2 (1.7) |

| Lymphocytes (%), mean (SD) | 33.6 (6.9) | 34.4 (7.5) | 32.7 (6.2) |

| Eosinophils (%), mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.1) | 3.1 (2.5) | 2.7 (1.6) |

| ESR (mm/h), mean (SD) | 15.3 (12.5) | 14.4 (11.9) | 16.3 (13.1) |

| T3 (pmol/L), mean (SD) | 4.1 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.4) |

| T4 (pmol/L), mean (SD) | 12.8 (1.4) | 12.9 (1.6) | 12.7 (1.2) |

| TSH (mlU/L), mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.8 (2.0) | 1.4 (0.7) |

| Cortisol (nmol/L), mean (SD) | 319.7 (122.8) | 310.9 (123.9) | 328.4 (122.2) |

| Number of abnormalities, n (%) | |||

| T3 | 3 (2.7) | 3 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| T4 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| TSH | 4 (3.6) | 4 (7.3) | 0 (0) |

| Cortisol | 6 (5.5) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (7.3) |

BMI, body mass index; PCFS, post-COVID-19 Functional Status; C19-YRSm, modified COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Survey; WBC, white blood cell; RBC, red blood cell; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; T3, triiodothyronine; T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone. Cs4 (intervention drug), Cordyceps sinensis mycelium culture extract.

Participants who received Cs4 had a significant decrease in long COVID symptoms at 12 weeks compared to the waitlist control group at 12 weeks (MD, −8.7; 95% CI, −12.7 to −4.8; P < 0.001) assessed by C19-YRSm after adjusting for the duration after the last COVID-19 infection ( Table 2 ) with a statistical power of 0.98. Similarly, participants receiving Cs4 achieved significant improvement at 12 weeks in fatigue compared to the waitlist control group assessed by the BFI (MD, −8.1; 95% CI, −14.2 to −2.0; P = 0.011), insomnia assessed by the ISI (MD, −2.9; 95% CI, −4.6 to 1.2; P = 0.001), respiratory symptoms assessed by the SGRQ (subscale symptoms MD, −6.1; 95% CI, −10.6 to 1.6; P = 0.009; subscale activity MD, −8.1; 95% CI, −15.1 to −1.2, P = 0.025; subscale total score MD, −6.3; 95% CI, −11.4 to −1.2; P = 0.018), and the quality of life assessed by SF-12 (physical component MD, 7.0; 95% CI, 4.2–9.8, P < 0.001; mental component MD, 6.8; 95% CI, 2.9–10.7, P < 0.001) but a non-significant difference in depression and anxiety assessed by the HADS (depression MD, −0.4; 95% CI, −1.6 to 0.7; P = 0.482; anxiety MD, −0.1; 95% CI, −1.2 to 0.9; P = 0.788) and the subscale impact of the SGRQ (subscale 3 MD, −5.3; 95% CI, −10.8 to 0.2; P = 0.064). The sensitivity analysis showed that the results of the primary outcome were robust (the sensitivity analysis of the C19-YRSm symptom severity from baseline to week 12 is provided in Supplement 2).

Changes in primary and secondary outcomes.

| Variables | Mean change from baseline (95% CI) | Between-group difference (raw) | Between-group difference (adjusted for duration) | Between-group difference (adjusted for vaccine doses) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs4 group (n = 55) | Waitlist control group (n = 60) | Cs4 group vs. control group | P Value | Cs4 group vs. control group | P Value | Cs4 group vs. control group | P Value | |

| C19-YRSm symptom severity | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −9.6 (−12.1 to −7.1) | −0.1 (−2.9 to 2.7) | −9.4 (−13.1 to −5.8) | <0.001 | −8.7 (−12.7 to −4.8) | < 0.001 | −9.9 (−13.7 to −6.2) | <0.001 |

| BFI | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −10.5 (−15.1 to −5.9) | −0.5 (−4.2 to 3.1) | −10.0 (−15.7 to −4.2) | 0.001 | −8.1 (−14.2 to −2.0) | 0.011 | −9.5 (−15.4 to −3.5) | 0.002 |

| ISI | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −3.9 (−5.2 to −2.5) | −0.6 (−1.6 to 0.3) | −3.2 (−4.8 to −1.6) | <0.001 | −2.9 (−4.6 to −1.2) | 0.001 | −2.9 (−4.5 to −1.3) | <0.001 |

| SGRQ symptoms | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −7.8 (−11.5 to −4.1) | −0.2 (−2.3 to 1.9) | −7.6 (−11.8 to −3.4) | <0.001 | −6.1 (−10.6 to 1.6) | 0.009 | −7.4 (−11.7 to −3.2) | <0.001 |

| SGRQ activity | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −10.8 (−16.3 to −5.3) | −0.6 (−4.1 to 2.9) | −10.2 (−16.5 to −3.8) | 0.002 | −8.1 (−15.1 to −1.2) | 0.025 | −9.4 (−15.9 to −2.9) | 0.006 |

| SGRQ impact | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −9.9 (−14.5 to −5.3) | −2.9 (−5.8 to −0.1) | −7.0 (−12.3 to −1.6) | 0.012 | −5.3 (−10.8 to 0.2) | 0.064 | −6.3 (−11.7 to −0.9) | 0.024 |

| SGRQ total score | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −9.6 (−13.9 to −5.3) | −1.8 (−4.0 to 0.6) | −7.8 (−12.6 to −3.1) | 0.002 | −6.3 (−11.4 to −1.2) | 0.018 | −7.4(−12.3 to −2.5) | 0.004 |

| HADS score | ||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −0.9 (−1.7 to −0.0) | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.3) | −0.5 (−1.6 to 0.5) | 0.345 | −0.4 (−1.6 to 0.7) | 0.482 | −0.6 (−1.7 to 0.5) | 0.281 |

| Anxiety | ||||||||

| Week 12 | −0.5 (−1.2 to 0.2) | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.3) | −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.9) | 0.832 | −0.1 (−1.2 to 0.9) | 0.788 | 0.0 (−1.0 to 1.1) | 0.924 |

| SF-12 score | ||||||||

| Physical component | ||||||||

| Week 12 | 6.6 (1.3 to 7.6) | −1.0 (−2.7 to 0.7) | 7.6 (−2.8 to 0.9) | <0.001 | 7.0 (4.2 to 9.8) | <0.001 | 7.7 (5.1 to 10.4) | <0.001 |

| Mental component | ||||||||

| Week 12 | 7.9 (4.8 to 10.9) | 0.4 (−1.7 to 2.5) | 7.5 (3.8 to 11.1) | 0.779 | 6.8 (2.9 to 10.7) | <0.001 | 7.4 (3.6 to 11.1) | <0.001 |

C19-YRSm, modified COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SF12, 12-Item Short Form Survey. Cs4 (intervention drug), Cordyceps sinensis mycelium culture extract.

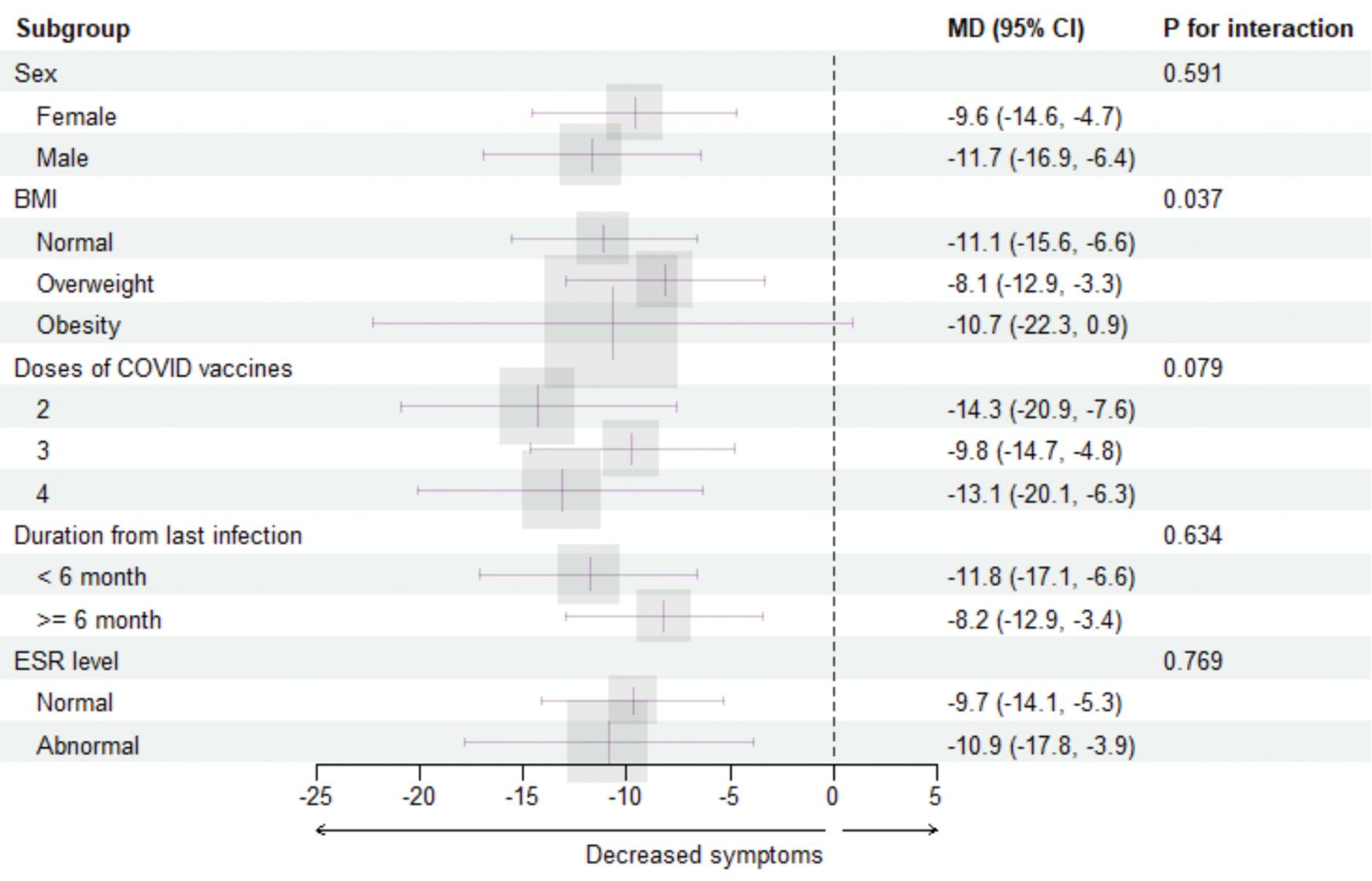

The effect of Cs4 on long COVID symptoms was consistent across most of the predefined subgroups, including female and male patients (P for interaction = 0.591), administration of 2, 3, and 4 doses of COVID vaccines (P for interaction = 0.079), <6 months and >6 months elapsed from last COVID infection (P for interaction = 0.634), and patients with a normal and abnormal ESR (P for interaction = 0.769; Figure 2 ). However, the effect was statistically different across patients with a normal BMI, overweight, and obesity (P for interaction = 0.037). Specifically, the long COVID symptom improvement difference between the Cs4 group and waitlist control group was significantly different from normoweight and overweight patients (normoweight patient MD, −11.1; 95% CI, −15.6 to −6.6; overweight patient MD, −8.1; 95% CI, −12.9 to −3.3).

Subgroup analysis of the primary outcomes stratified by potential effect modifiers.

BMI, Body Mass Index; PCFS; ESR, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

The adverse events at 24 weeks, which were all mild, included exacerbated or new onset abnormal AST level (Cs4 group 4 [7.3%] vs. waitlist control group 1 [1.8%]; P= 0.174), ALT level (3 [5.4%] vs. 0 [0%]; P = 0·081), creatinine level (1 [1.8%] vs. 0 [0%]; P = 0.316), urea level (4 [7.3%] vs. 1 [1.8%]; P = 0.174), and creatine kinase level (4 [7.3%] vs. 1 [1.8%]; P = 0.174). None of the adverse events were likely to be associated with the study products, as determined by an independent safety adjudication committee. Of the participants, 84% in the Cs4 group and 73% in the waitlist control group were administered 100% of the study products (P = 0.407) ( Table 3 ).

Adverse events, study compliance, and viral infection during the study period.

| Variables | Overall (n = 110) | Cs4 group (n = 55) | Waitlist control group (n = 55) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events (exacerbation/new onset of abnormality), n (%) | |||

| Aspartate transaminase (AST) | 5 (4.5) | 4 (7.3) | 1 (1.8) |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (5.4) | 0 (0) |

| Creatinine | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| Urea | 5 (4.5) | 4 (7.3) | 1 (1.8) |

| Creatine kinase | 5 (4.5) | 4 (7.3) | 1 (1.8) |

| Study compliance, n (%) | |||

| Taking 100% of study products | 86 (0.78) | 46 (0.84) | 40 (0.73) |

| Viral infection during study period, n (%) | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 5 (4.5) | 4 (7.3) | 1 (1.8) |

| Flu | 4 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) |

Cs4 (intervention drug), Cordyceps sinensis mycelium culture extract.

4. DISCUSSION

Cs4 intervention demonstrated superior symptom improvement compared to no Cs4 intervention. Participants in the Cs4 group showed significantly greater improvement in the primary outcome, which was measured as the change in the symptom severity dimension of the C19-YRSm. Cs4 displayed a larger clinically meaningful effect for the primary outcome when compared to no Cs4 intervention. Moreover, secondary outcomes, including fatigue, insomnia, respiratory symptoms, and quality of life, were also significantly different across the two groups. However, there was no improvement in depression and anxiety observed in the Cs4 group compared to the waitlist control group. Furthermore, no severe adverse events related to the interventions were reported among the participants.

The efficacy of a symbiotic preparation (SIM01) in alleviating multiple symptoms of PACS was evaluated in a prior randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [28]. The SIM01 group (n = 232) exhibited significantly higher rates of improvement in fatigue, memory loss, concentration difficulties, gastrointestinal disturbances, and overall unwell feeling compared to the placebo group after 6 months (n = 231) [28]. This study and the current study investigated post-COVID fatigue, despite differences in intervention. Another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examined the impact of Cs4 on the exercise capacity of healthy elderly individuals [29]. After 6 weeks of Cs4 intake there were significant increases in the VO2max and VO2θ, while no changes were observed after placebo administration. This finding suggests that Cs4 enhanced oxygen uptake, aerobic capacity, ventilation function, and resistance to fatigue in elderly individuals during exercise. The findings herein are consistent with previous findings that suggested that Cs4 can relieve fatigue, although the fatigue previously studied was not related to post-COVID symptoms. Combining the findings of the previous study with the current study provides strong evidence for Cs4 efficacy in alleviating post-COVID symptoms, such as fatigue, suggesting the potential in alleviating post-COVID symptoms.

The current study is the first clinical trial related to Cs4 treatment for long COVID symptoms; no similar clinical trials have been previously conducted. Several strengths were identified in the current study. The current study was a randomized trial in which participants were randomly assigned to the Cs4 or waitlist control group to minimize the potential influence of confounding factors. With the two groups in the current study displaying balanced baseline characteristics, which ensured comparability and minimized selection bias, it is more likely that the 110 participants represented a broader population of Hong Kong residents. Additionally, the estimated power was 83% compared to 80% in the sample size calculation. The heightened estimated power fostered increased confidence in the reliability of the study results, improved the precision of the study findings, and led to a more accurate representation of reality. Moreover, the current study utilized the C19-YRSm, a validated scale specifically designed to be sensitive and specific in measuring long COVID symptoms, which ensured accurate assessment. This scale has undergone rigorous testing to ensure reliability and validity. Therefore, the current study results can provide accurate evidence. Furthermore, multiple scales were used to assess symptoms. The BFI, ISI, HADS, and SGRQ scales were used as secondary measures to reevaluate fatigue, insomnia, mood changes, and respiratory symptoms present in C19-YRSm. This comprehensive approach facilitated generation of robust results and reduced information bias.

As a waitlist-controlled clinical study, some limitations were encountered. First, performance bias was possible because the participants were not blinded across groups, which likely left participants with different expectations towards the interventions across groups. To address this concern, data were utilized from 0–12 weeks. However, this approach led to another limitation. Specifically, there was an inability to conduct follow-up comparisons, which prevented the evaluation of CS4 long-term effects. Additionally, the primary outcome focused on overall symptom severity, while the secondary outcomes were limited to fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, depression, respiratory outcomes, and quality of life. However, Cs4 may also have potential effects on other symptoms of long COVID that were not explored in the current study. Moreover, blinding was impractical in this waitlist-controlled clinical study. It is possible that a lack of blinding introduced performance and reporting bias. Furthermore, while the primary outcomes were based on well-validated scales related to long COVID, the scales used for secondary outcomes were not directly related to long COVID. Using a measurement tool that is not well-validated for assessing long COVID symptoms may lack the sensitivity and specificity needed to accurately capture the true nature of these symptoms, leading to potential inaccuracies in assessment.

In conclusion, the findings herein suggest that Cs4 may be a beneficial treatment for multiple long COVID symptoms, especially fatigue, insomnia, and respiratory symptoms, while also enhancing both mental and physical well-being. However, emotional changes, including depression and anxiety, were not addressed. Corollary studies on the long-term efficacy of Cs4 are warranted with a focus on maintaining efficacy. Additionally, investigation into the pharmacologic mechanisms underlying Cs4 in addressing long COVID symptoms, especially fatigue, insomnia, and respiratory symptoms, should be pursued to deepen our understanding of this promising therapeutic approach.