1. INTRODUCTION

Bladder, renal and prostate tumors, the most prevalent malignancies in the genitourinary system, are all closely associated with age. Prostate cancer (PCa) continues to be among the top three malignancies in men, in terms of prevalence and death rates (27% and 11%, respectively, in the United States) [1]. Despite major advancements in treatment, PCa continues to pose a serious health risk to men worldwide [2–4]. Therefore, several therapy options must be considered. One new cancer hallmark included in 2022 is cellular senescence. Senescent cells perform dual roles in a variety of malignant processes [5]. Another recently discovered hallmark of cancer is non-mutational epigenetic reprogramming, in which long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play a key role [5]. Transcripts that are longer than 200 nt and do not encode proteins are known as lncRNAs. These RNAs regulate gene expression at the epigenetic, translational and post-translational levels. Notably, lncRNAs appear to be associated with cellular senescence [6–8], and increasing evidence indicates critical roles of lncRNA expression in cancers [9, 10]. Studying senescence and lncRNAs in PCa could therefore guide both basic research and clinical treatment.

LncRNAs are abnormally expressed in a variety of cancers, including PCa. Numerous studies have examined the relationships between lncRNAs and PCa. For instance, prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA 3), one of the most accurate biomarkers for PCa, functions as a lncRNA and modulates androgen receptor (AR) signal transduction and cell growth [11]. Second chromosomal locus associated with prostate-1 (SChLAP1), a lncRNA that is highly expressed in 25% of PCa, is likewise involved in PCa metastasis and adverse outcomes in patients with PCa [12]. In addition, Singh et al. have recently identified lncRNA H19 as a potential biomarker for neuroendocrine PCa diagnosis and prognostication [13]. They have demonstrated that lncRNAs are useful in both prognosis and treatment, even in patients with the deadly subtype of PCa that is resistant to castration. However, studies investigating that the relationship between lncRNAs and PCa from a perspective of senescence remain lacking.

In this study, by integrating multiple analytic methods, we constructed and validated two novel prognostic subtypes of patients with PCa by using senescence-associated lncRNAs. The distinct characteristics of these two subtypes regarding prognosis and androgen response may aid in the future PCa research and clinical therapy.

2. METHODS

2.1 Data preparation

We downloaded a list of 279 human genes driving cellular senescence from the CellAge database (http://genomics.senescence.info/cells) [14]. We used the PCa gene matrix and clinical features in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database from our pervious study [3]. Biochemical recurrence (BCR)-associated lncRNAs and differentially expressed lncRNAs were examined. Differential expression was defined by a fold-change absolute value >1.5 and an adjusted p value <0.05. The senescence-associated lncRNAs were identified with Pearson analysis, on the basis of a p value <0.5 and absolute value of the coefficient >0.4. A total of 430 samples from the TCGA database were examined, and the log-rank test for BCR-free survival was significant, at p <0.05. Through intersection of differentially expressed, BCR-associated and senescence-associated lncRNAs, we identified lncRNAs that were used to group 430 patients with PCa undergoing radical prostatectomy in TCGA database by using the nonnegative matrix factorization algorithm. We used two additional Gene Expression Omnibus datasets (GSE46602 [15] and GSE116918 [16]) to externally validate the subtypes identified in TCGA database. The prognosis and clinical traits of molecular subtypes were also analyzed.

2.2 Mutational landscape and functional differences between subtypes

TCGA (https://portal.gdc.com), a database containing information on PCa, was the source of the downloaded RNA-sequencing profiles, genetic mutations and related clinical data. Using the maftools package in the R programming language, we downloaded and displayed the mutational data. Differences in mutational frequency between subtypes were also assessed. In functional analysis, we performed gene set enrichment analysis with “c2.cp.kegg.v7.4.symbols.gmt” and “h.all.v7.4.symbols.gmt” from the molecular signatures database [17, 18]. The minimal gene set was determined to be 5, whereas the maximum gene set was established to be 5000, on the basis of gene expression and subtypes. Resampling was performed 1000 times. A false discovery rate of 0.10 and a p value of 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

2.3 Tumor stemness and heterogeneity analyses

Tumor stemness indexes included stemness scores based on differentially methylated probes, DNA methylation-based stemness, enhancer element/DNA-methylation-based stemness, epigenetically regulated DNA-methylation-based stemness, epigenetically regulated RNA-expression-based stemness and RNA-expression-based stemness [19]. Tumor heterogeneity included homologous-recombination deficiency (HRD), loss of heterozygosity, neoantigens, tumor ploidy, tumor purity, mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity, tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability [20, 21]. The results of the above indicators were obtained from our previous study [22]. We compared the differences in two subtypes with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

2.4 Tumor microenvironment assessment

By using the TIMER and ESTIMATE algorithms, we determined the overall tumor microenvironment and immune component assessments [23–25]. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the 54 immune-checkpoint differences and tumor microenvironment scores between subtypes. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of our study.

2.5 Statistical analysis

We performed the analysis in R 3.6.3 with the appropriate tools. For data with a non-normal distribution, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A Kaplan-Meier curve representing the results of the log-rank test was used for survival analysis. The threshold for statistical significance was a two-sided p <0.05. Significance is indicated as follows: not significant (ns), p≥0.05; *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; *** and p<0.001.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Identification of senescence-associated lncRNA subtypes and their applications

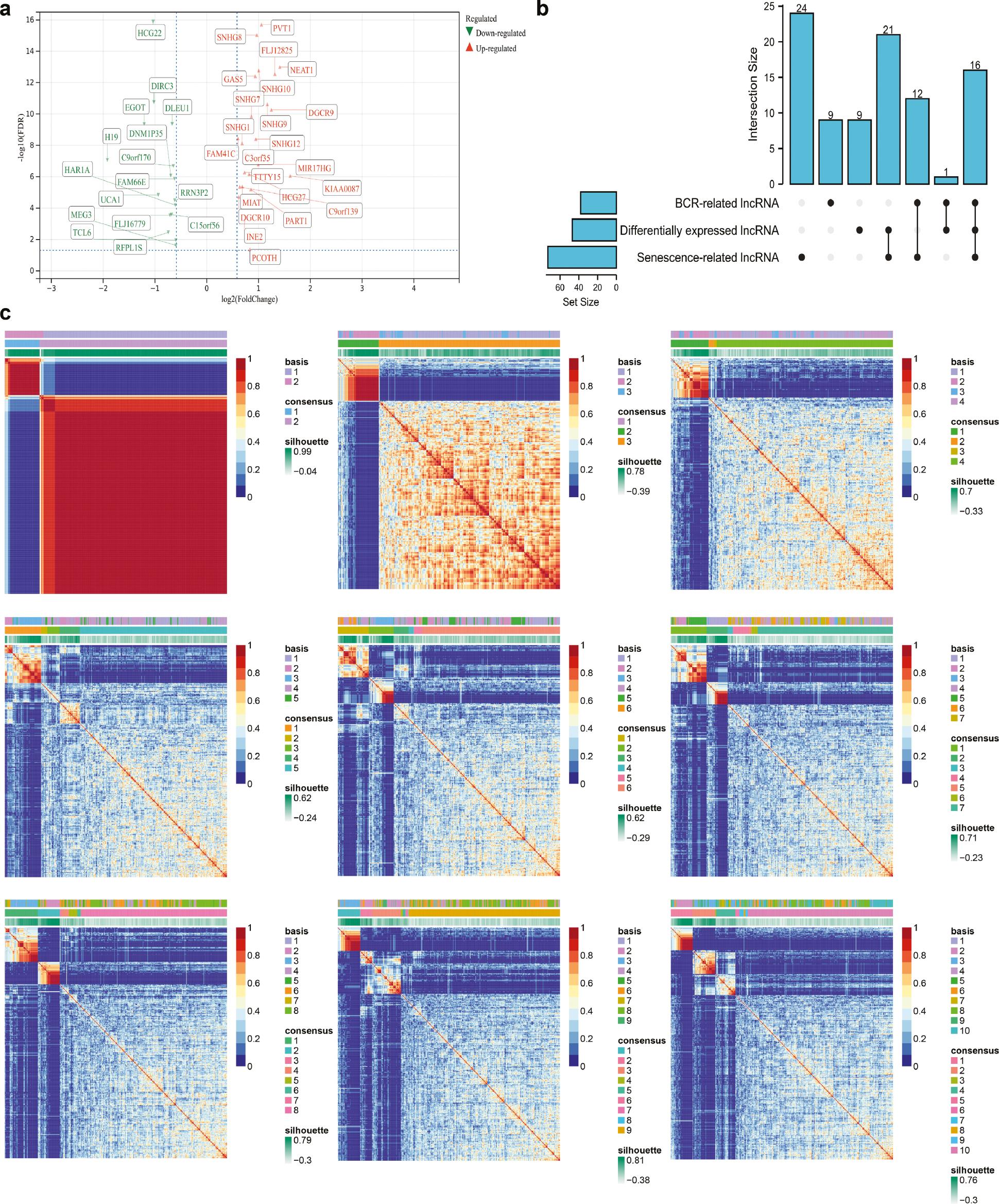

We detected 47 lncRNAs that were differentially expressed between 498 tumor and 52 normal PCa samples in TCGA database ( Figure 2a ). A total of 38 BCR-associated lncRNAs and 73 senescence-associated lncRNAs were detected. Through intersection, we identified 16 differentially expressed lncRNAs associated with BCR and senescence ( Figure 2b ). Subsequently, we used small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 (SNHG1), myocardial infarction associated transcript (MIAT) and small nucleolar RNA host gene 3 (SNHG3) to group the 430 patients in TCGA database, then performed Cox regression analysis including the above 16 lncRNAs ( Figure 2c ). Among the various subtypes ( Figure 2c ), two molecular subtypes were significantly associated with BCR-free survival, and subtype 2 was prone to BCR (HR: 19.62, p <0.001; Figure 3a ). In GSE116918 [16], the three genes were used to divide the 248 patients undergoing radical radiotherapy into two subtypes ( Figure 3b ); subtype 2 had significantly higher risk of BCR than subtype 1 (HR: 27.48, p <0.001; Figure 3c ). Similar results were observed for GSE46602 [15] ( Figure 3d-e ). In addition, the baseline characteristics, e.g., Gleason score and T stage, were balanced between subtypes in both TCGA database ( Table 1 ) and the GSE116918 [16] dataset ( Table 2 ).

Identification of TCGA subtypes.

(a) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed lncRNAs in TCGA database. (b) UpSet plot showing the intersection of senescence-associated, differentially expressed and BCR-associated lncRNAs in the TCGA database. (c) Heatmap plot showing all subtypes in TCGA database, on the basis of the nonnegative matrix factorization algorithm. lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; BCR, biochemical recurrence.

Prognostic value of subtypes and pathway analysis.

(a) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the BCR-free survival difference in TCGA database. (b) Heatmap plot showing two distinct subtypes in GSE116918. (c) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the BCR-free survival difference in GSE116918. (d) Heatmap plot showing two distinct subtypes in the GSE46602. (e) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the BCR-free survival difference in GSE46602. (f) Hallmark gene set analysis of TCGA subtypes. (g) KEGG pathway differences in TCGA subtypes. (h) Forest plot showing results of tumor heterogeneity and stemness between TCGA subtypes. (i) Waterfall plot showing the top ten differentially mutated genes between TCGA subtypes. BCR, biochemical recurrence.

Differences in clinical characteristics between two prostate cancer subtypes in TCGA.

| Characteristic | Subtype 1 | Subtype 2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | 355 | 75 | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 61 (56, 66) | 62 (57, 66) | 0.495 |

| Gleason score, n (%) | 0.147 | ||

| 6 | 32 (7.4%) | 7 (1.6%) | |

| 7 | 177 (41.2%) | 29 (6.7%) | |

| 8 | 50 (11.6%) | 9 (2.1%) | |

| 9 | 96 (22.3%) | 30 (7%) | |

| T stage, n (%) | 1.000 | ||

| T2 | 128 (30.2%) | 27 (6.4%) | |

| T3 | 215 (50.7%) | 46 (10.8%) | |

| T4 | 7 (1.7%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.317 | ||

| Asian | 9 (2.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Black or African American | 45 (10.8%) | 5 (1.2%) | |

| White | 288 (69.2%) | 67 (16.1%) | |

| N stage, n (%) | 0.901 | ||

| N0 | 253 (67.5%) | 53 (14.1%) | |

| N1 | 56 (14.9%) | 13 (3.5%) | |

| Residual tumor, n (%) | 0.272 | ||

| No | 230 (54.9%) | 43 (10.3%) | |

| Yes | 116 (27.7%) | 30 (7.2%) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Differences in clinical characteristics between prostate cancer subtypes in GSE116918.

| Characteristic | Subtype 1 | Subtype 2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 226 | 22 | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 68 (63.25, 72) | 69.5 (62.5, 73) | 0.534 |

| T stage, n (%) | 0.095 | ||

| T1 | 48 (21.5%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| T2 | 69 (30.9%) | 7 (3.1%) | |

| T3 | 83 (37.2%) | 9 (4%) | |

| T4 | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (0.9%) | |

| Gleason score, n (%) | 0.075 | ||

| 6 | 42 (16.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 7 | 89 (35.9%) | 10 (4%) | |

| 8 | 45 (18.1%) | 7 (2.8%) | |

| 9 | 50 (20.2%) | 5 (2%) | |

| BCR, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 182 (73.4%) | 10 (4%) | |

| Yes | 44 (17.7%) | 12 (4.8%) | |

| Metastasis, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| No | 211 (85.1%) | 15 (6%) | |

| Yes | 15 (6%) | 7 (2.8%) |

IQR, interquartile range.

3.2 Functional enrichment, mutated genes, tumor heterogeneity and stemness

In hallmark gene set enrichment, protein secretion and AR were highly enriched in subtype 1, and the G2M checkpoint was highly enriched in subtype 2 ( Figure 3f ). In pathway analysis, spliceosomes, base excision repair and the cell cycle were highly enriched in subtype 2 ( Figure 3g ). Regarding tumor heterogeneity and stemness, HRD and TMB were significantly higher in subtype 2 than subtype 1 ( Figure 3h ). The top ten significantly differentially expressed genes between subtype 2 and subtype 1 were CUBN, DNAH9, PTCHD4, NOD1, ARFGEF1, HRAS, PYHIN1, ARHGEF2, MYOM1 and ITGB6 ( Figure 3i ).

3.3 Tumor immune microenvironment and immune checkpoints

Among immune checkpoints, the expression levels of CTLA4, ICOS, TNFRSF18, TNFRSF4, TNFRSF25, LAG3, TNFRSF8, CD80, ADORA2A and CD276 were significantly higher in subtype 2 than in subtype 1 ( Figure 4a ). Only CD47 was significantly higher in subtype 1 than subtype 2 ( Figure 4a ). In the overall assessment, no significant difference was detected between subtypes, whereas the B cell scores were significantly higher in subtype 1 than subtype 2 ( Figure 4b ).

4. DISCUSSION

After thorough validation, we identified two distinct prognosis-associated subgroups of patients with PCa. Subtype 2, with a poorer prognosis, was distinguished from subtype 1 by the lncRNAs SNHG1, MIAT and SNHG3. Importantly, according to our hallmark gene set enrichment analysis, this typing system aids in identifying patients who are not susceptible to androgens. Additionally, the main differences between subtypes and their probable causes were determined through investigation of tumor heterogeneity, the mutational landscape and PCa immunity.

SNHG1, MIAT and SNHG3 were lncRNAs differentially expressed between cancerous tissues and adjacent normal tissues. SNHG1 is a novel lncRNA whose high expression and carcinogenic characteristics have been confirmed in various cancers [26–29]. In PCa, SNHG1 mediates malignant transformation by promoting tumor proliferation, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, primarily through a competing endogenous RNA mechanism [29–31]. Additionally, studies on SNHG3 and PCa have shown similar results to studies on SNHG1. Interactions between SNHG3 and microRNA epigenetically regulate PCa progression [32–34]. Although the role of MIAT in PCa remains to be clarified, Crea et al. have suggested that MIAT also promotes neuroendocrine PCa initiation and progression [35]. Nonetheless, our experimental data and validation suggested that patients in subtype 2 were prone to BCR, on the basis of typing according to those three lncRNAs.

Because lncRNAs function primarily as epigenetic modulators, we conducted hallmark gene set enrichment analysis. We observed clear enrichment in genes associated with AR in subtype 1, in which patients had better prognosis. Androgen dependence is a typical characteristic of primary PCa [36]. After ARs receive signals from androgens and associated products, they initiate the activation and transduction of a series of signaling pathways via a complex intracellular signaling network. Mechanically, AR is a transcription factor involved in the cell cycle, prostate development and other key activities, and it has been found to promote PCa growth [37]. Therefore, androgen-deprivation therapy was the traditional treatment for PCa [38]. However, patients with PCa who undergo androgen-deprivation therapy subsequently experience recurrence and therapy resistance, and develop castration-resistant PCa after 18–36 months [39, 40]. Androgen-independent abnormal reactivation of AR signals results in such cancer progression [41]. Although novel second-generation AR antagonists, such as enzalutamide and abiraterone, may work temporarily, patients still encounter inevitable drug resistance, disease progression and even lethal outcomes [38]. Hence, androgen sensitivity and response are critical in the prognosis of patients with PCa. Accordingly, enriched AR genes may be considered the key factors associated with the better prognosis in subtype 1. Moreover, a recent study has shown indicated that molecular modulation and interactions between other proteins and DNAs are involved in the resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone [42]. Accordingly, we hypothesized that altered expression of the three lncRNAs in subtype 2 might also account for the altered AR characteristics and consequently the poor prognosis, from an AR-epigenetic modulation perspective. In contrast, G2M-checkpoint-associated genes were enriched in subtype 2. Tumors cannot grow without constant and infinite mitosis, and the G2M checkpoint determines whether cells enter the M stage of the cell cycle. Several lncRNA have been confirmed to interfere with the normal cell cycle by targeting the G2M checkpoint [43–45]. Subsequently, our hypothesis that the expression of the lncRNAs SNHG1, MIAT and SNHG3 promotes malignant proliferation in PCa may be a reasonable explanation for the short BCR-free survival among patients with subtype 2 PCa. Our pathway analysis provided evidence supporting that possibility: pathways associated with cell proliferation and cell death, including spliceosomes, base excision repair and the cell cycle, were highly enriched in subtype 2. Together, the three lncRNAs identified herein may regulate AR activity and the cell cycle in PCa cells, thus providing a basis for our subtyping analysis.

We also identified mutated genes in the two subtypes: CUBN, DNAH9 and PTCHD4 were the top three mutation genes. CUBN, a co-transporter located primarily in absorptive epithelia, promotes the uptake of specific ligands, such as hemoglobin, lipoprotein and iron [46]. The expression of CUBN is associated with the initiation and progression of renal clear cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer and breast cancer [47–49]; moreover, low CUBN expression is significantly associated with poor prognosis [49]. The loss of DNAH9 often occurs in tumors, and Donner et al. have revealed that DNAH9 may possess antitumor effects [50]. Furthermore, epigenetic regulation of PTCHD4 splicing decreases tumor growth, thus indicating a potential role of PTCHD4 in PCa [51]. Targeting these top mutated genes might improve the prognosis of subtype 2 patients.

Because tumor immunity has non-negligible effects on patient prognosis, we analyzed several immunity-associated indicators to better interpret our typing mechanisms. In the tumor immune microenvironment (TME), immune silencing and immunosuppressive status have long been considered characteristics of PCa immunity [52]. In our TME score analysis, we observed that infiltrating immune and immune-associated cells in subtype 2 did not substantially differ from those in subtype 1 (except for B cells), and the difference in immune infiltrating status between subtypes was not sufficient to alter patient prognosis. However, our subsequent findings may advance current viewpoints regarding PCa immunotherapy. The TMB and HRD were significantly higher in subtype 2 than subtype 1. TMB indicates the total number of mutations and the degree of tumor heterogeneity [20, 21]. On the basis of the hypothesis that mutant proteins would increase the number of antigenic peptides and generate new immunogenic antigens [53, 54], TMB may be applied to predict therapeutic responses to immune-checkpoint blockade and identify patients who might benefit most from treatment. Importantly, increasing evidence suggests that cellular heterogeneity does not simply result from transcriptional processes but instead has an epigenetic basis, in which histone modifications, nucleosome positioning and chromatin accessibility have been demonstrated to be involved, and lncRNAs may also play a role [55]. In addition, HRD is a key therapy response indicator that results in specific and stable genomic changes in PCa [56, 57]. Changes in the two indicators of tumor heterogeneity may suggest that our typing system could be applied to identify specific patient populations that might benefit most from immunotherapy. In addition, most significantly differentially expressed immune checkpoints in our analysis had higher expression in subtype 2 than subtype 1, thereby suggesting a relatively more active immune TME with more potential therapy targets in subtype 2.

In summary, our study established two novel prognostic subtypes that were closely associated with BCR-free survival in patients with PCa, and suggested that the AR may play a critical role. Our typing system additionally indicated immune status. Therefore, our study may guide the clinical management of patients with PCa. However, further studies and experiments will be necessary to reveal the detailed mechanisms.