1. INTRODUCTION

Pneumonia is an infectious condition wherein the air sacs in one or both lungs are inflamed. The air sacs may fill with fluid or pus, thus causing cough with phlegm or pus, and leading to difficulties in breathing, fever and chills. In children under 5 years of age who have cough and/or difficulty breathing, with or without fever, pneumonia is diagnosed according to the presence of either rapid breathing or a drawn-in lower chest wall, such that the chest moves in or retracts during inhalation [1]. Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is predominantly a disease due to a weakened immune system. It manifests primarily in infants and young children, people older than 65 years and people with underlying health problems [2]. A variety of organisms, such as bacteria, viruses and fungi, can cause pneumonia and simultaneously increase the risk of hospitalization [3, 4]. Pneumonia is a heterogeneous disease categorized into two subclasses (viral and bacterial). The clinical presentation of viral and bacterial pneumonia is similar; however, the symptoms of viral pneumonia, such as wheezing, may be more numerous than those of bacterial pneumonia [5]. The severity of this disease can range from mild to life threating [6]. Severely ill patients require hospitalization; moreover, severely ill infants may be unable to eat or drink, and may also experience unconsciousness, hypothermia and convulsions [7] Several risk factors, such as infancy, premature birth, incomplete immunization, maternal smoking or household tobacco smoke exposure, indoor air pollution, low birthweight, malnutrition, lack of exclusive breastfeeding and overcrowded living environments, have been indicated to increase the chances of CAP onset [8, 9]. Pneumonia can spread in multiple ways. The viruses and bacteria that are found in the nose or throat can infect the lungs if they are inhaled. They may also spread via airborne droplets from coughs or sneezes [10], In addition, pneumonia may spread through the blood during and shortly after birth [11]. Pneumonia is treated with antibiotics, and amoxicillin is the first line of treatment [12]. The most effective preventive measure against this disease is immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), pneumococcus, measles and whooping cough (pertussis) [13]. Adequate nutrition improves children’s natural defenses, starting with exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life [14]. Encouraging good hygiene and providing affordable clean indoor stoves (in crowded homes) helps decrease pneumonia infection [15]. Children infected with HIV are given cotrimoxazole daily to decrease the risk of contracting pneumonia [16].

Medical practitioners may perform multiple diagnosis tests if pneumonia is suspected. Clinically, CAP presents as tachypnoea, hypoxia, cough, fatigue, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain and an elevated rate of breathing [17]. Depending on the pathogen, a patient’s cough may be persistent and dry or may produce sputum [18]. The etiological diagnosis of CAP is attributed primarily to viral infections, mostly by respiratory syncytial virus, which is more common in young children (1–6 years) compared to older children (7–12 years) [19]. In older children, the most identified pathogen is Streptococcus pneumoniae, followed by mycoplasma and chlamydia [20]. Modalities available for etiological diagnosis include molecular diagnostics, microscopy, culture and antigen detection [21]. Both bacterial and viral pneumonia exhibit a wide distribution of acute phase reactants (blood count, C reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) [19]. Upper-respiratory-tract secretions are useful in virological diagnosis. Pulmonary tuberculosis should be considered in children presenting with severe pneumonia or pneumonia with a known tuberculosis contact [22]. The radiological signs of pneumonia overlap with those of collapse. Chest radiography cannot distinguish between viral and bacterial infection, and is unable to detect early changes in pneumonia [9]. However, chest radiography somewhat improves the diagnosis of pediatric CAP and may prevent overtreatment with antibiotics [23].

Reported cases of pneumonia have increased over the past 10 years (since 2013), probably because of rapid increases in cases among children, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and in East Asian countries, such as Korea, Japan and China [21]. Statistics have indicated that pneumonia is a leading cause of death worldwide, and that CAP is the most common type of pneumonia (pulmonary parenchymal infection), because it is acquired outside of hospitals and other healthcare facilities [2, 24, 25]. Although antibiotic therapies are available for treatment and management of CAP, they can lead to antibiotic resistance and also carry a risk of long-term morbidity and mortality [26, 27]. The use complementary therapeutic interventions, such as systematic corticosteroid administration, has been found to improve the outcomes of patients with CAP [28–30]. Patients with CAP show elevated pulmonary and circulating inflammatory cytokine concentrations, which serve as an effective mechanism for the elimination of invading pathogens [31]. This excessive local inflammatory response causes the pulmonary compartment to fill, thereby resulting in spillover of cytokines into the systemic circulation and generating the systemic inflammatory response associated with severe CAP [32]. The excess release of inflammatory cytokines can be harmful and can cause pulmonary dysfunction [31, 33]. In contrast, a decreased inflammatory reaction in immunosuppressed patients or older people can be dangerous and can lead to poorer outcomes. Corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory, vasoconstrictive and immune-suppressive properties [34]. They function primarily by modulating transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms in cellular nuclei, thus decreasing the production of inflammatory mediators [35]. These properties may be favorable in patients with CAP. Positive effects of corticosteroids in CAP were reported in patients with pneumococcal pneumonia in the 1950s [36], and since then, the adjunctive use of corticosteroids in the treatment of CAP has been discussed. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have investigated the efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for CAP. Furthermore, several systematic reviews of such clinical questions have been conducted [37–40]. However, because most of the study search was performed more than 5 years ago, the results of recent studies such as Wittermans et al. [41] were not included in those reviews. Here, we performed a new systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to assess the efficacy of corticosteroids for CAP.

2. METHODS

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and Interventions. This study was performed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement for healthcare interventions [42]. The methods were based on recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration, and the results were evaluated according to Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines [43].

2.1 Search strategy

Our search strategy was developed on the basis of best practices for systematic reviews. To identify relevant studies, we performed an extensive search across five electronic full-text databases: Medline/PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Scopus and Web of Science, with no language restrictions. Table 1 provides information on the databases. The databases were searched with variations on the keywords “CAP” AND “corticosteroid,” as shown in Table 2 . Database-specific Boolean search strategies were developed and followed the general format: “corticosteroid” terms AND/OR “CAP” terms. We searched articles published from January 1967 to June 2022 through a protocol designed for this study.

Databases searched in the systematic review.

| Databases | URL |

|---|---|

| Web of science | www.webofknowledge.com |

| Medline/PubMed | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| Embase | www.embase.com |

| Scopus | www.elsevier.com |

| The Cochrane Library | www.cochranelibrary.com/ |

| World Health Organization | www.who.int/health-topics/pneumonia |

2.2 Study selection, quality assessment and data extraction

Study titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers, and full-text screening was subsequently performed. The literature selection process was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement [44]. The quality of the selected studies was assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tools for RCTs. The data extracted included the following information: first author, year of publication, population in each group, antibiotic treatment (macrolides/comparator) and outcomes (mortality, durations of fever and hospitalization and therapeutic efficacy). Therapeutic (clinical) efficacy was defined as the rate of achieving clinical recovery with no fever, cough improvement/disappearance, and improved or normal laboratory values. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. When the results of the selected studies were unclear or missing, we contacted the corresponding study investigators to obtain or confirm data.

2.3 Eligibility criteria

Articles that met the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) the study topic was CAP, defined as a disease showing no clinical or radiological improvement 48–72 h after macrolide administration; (2) the participants were patients diagnosed with CAP; (3) the study was designed as an RCT or clinical trial (CT); (4) the intervention agent was a corticosteroid known to be active against CAP, such as methylprednisolone; (5) the control was a placebo; and (6) the study reported mortality rates as in-hospital, 30-day mortality or mortality without an explanation. Animal and preclinical studies, as well as articles other than original research (e.g., reviews, editorials, letters, conference abstracts or commentaries) and observational studies were excluded. Studies with duplicate participants (i.e., different studies with the same outcome indicators in the same number of patients) were also excluded. Our search strategy implemented no language restrictions, and non-English articles were translated and included in the evaluation.

2.4 Data synthesis

A systematic narrative synthesis is provided, with the information presented in text and tables, to summarize and explain the characteristics and findings of the included studies. The following is a brief outline of how we synthesized the findings: first, CAP in patients with CAP manifestations/those presenting with CAP symptoms was summarized, including definitions provided by CAP researchers. Second, the antecedents of CAP in these patients were summarized, including the grouping of corticosteroid therapies in the treatment of CAP in patients in the literature. Finally, the evidence of recent advances in efficacy of corticosteroid therapies in the treatment of CAP was incorporated into the theoretical framework.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed from July to August 2022. We pooled the findings from the included studies, including calculated mean, standard deviation and sample size. All statistical analysis and meta-analysis were performed in IBM SPSS 21 and Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK). Dichotomous data were analyzed with relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Continuous data were analyzed as mean differences and 95% CIs when the measurements used the same scale. The pooled RR was calculated with the random-effect model with the Mantel-Haenszel method. For the assessment of statistical heterogeneity, we used the I2 statistic. Significant heterogeneity was defined by an I2 statistic exceeding 50%. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered significant, and was calculated with the z test, with the null hypothesis indicating no average effect in the random-effect model of corticosteroids vs. placebo.

We performed predefined the following subgroup analyses of mortality according to the effects model: mortality type, duration of corticosteroid treatment, severity of CAP, use of loading dose, cumulative dose of corticosteroids, effective pharmacological effect achieved and inflammatory response. The stability of the results was confirmed with sensitivity analysis.

2.6 Risk of bias assessment

To assess the risk of publication bias, we used funnel plots for visual inspection. The strength of the body of evidence was assessed with the GRADE approach [18]. As recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [45], domains of bias of the studies included for the efficacy of the results were reviewed, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and staff, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other biases (including the balance among patients with diabetes, asthma, and shock; whether the trial was terminated early; and sponsor bias). Domains of bias of the studies that met more than six, four to six, and fewer than four items were considered high, fair and poor quality, respectively. The quality of evidence of the mortality and adverse events was evaluated according to the GRADE methods. Risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias were evaluated and classified as very low, low, moderate or high [43].

3. RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of the included studies

Nine RCTs on corticosteroids vs. placebo involving 2673 patients were included in this meta-analysis [41, 46–53]. The intervention group comprised 1335 individuals, and the control group comprised 1338 individuals. The RCTs were either multicenter [41, 46, 48–50, 52] or single-center [47, 50, 51] studies. Six studies were double-blind RCTs. The sample sizes ranged from 31 to 785 hospitalized patients with CAP ≥18 years of age. The type of corticosteroid treatment received by patients varied and comprised dexamethasone [41, 49], prednisone [46, 52], methylprednisolone [48, 53], prednisolone [47, 51] or hydrocortisone [50]. Similarly, the length of corticosteroid use varied from 3 to 7 days (mean 5.22±1.787 days). A placebo was used in the control group in all studies. Studies often excluded patients at high risk of adverse effects from corticosteroids. The characteristics of the included studied are illustrated in Table 3 , and their efficacy outcomes are shown in Table 4 . The severity of CAP differed in most studies: two studies involved patients with severe CAP, with a mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation Simplified Acute Physiology Score II score of approximately 15 or a Pneumonia Severity Index score VI-V rate > 50%; six studies involved patients with mixed CAP (mild to severe), and one study involved patients with less severe CAP. No study in abstract form was found.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Country | Study design | Total number of patients | Corticosteroid | Dose | Duration (days) | Cumulative corticosteroid dose | CAP severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wittermans et al., 2021 [41] | Netherlands | MC, DB, RCT | 401 | Dexamethasone (n=203) | 6 mg/day, oral | 4 | 24 mg | Mixed |

| Blum et al., 2015 [46] | Switzerland | MC, DB, RCT | 785 | Prednisone (n=392) | 50 mg/day, oral | 7 | 350 mg | Mixed |

| Snijders et al., 2010 [47] | Netherlands | SC, DB, RCT | 213 | Prednisolone (n=104) | 40 mg/day | 7 | 280 mg | Mixed |

| Torres et al., 2015 [48] | Spain | MC, DB, RCT | 120 | Methylprednisolone (n=61) | 0.5 mg/kg per 12 hrs | 5 | N/A | Severe |

| Meijvis et al., 2011 [49] | Netherlands | MC, DB, RCT | 304 | Dexamethasone (n=151) | 5 mg/day, IV | 4 | 20 mg | Mixed |

| Confalonieri et al., 2005 [50] | Italy | MC, DB, RCT | 48 | Hydrocortisone (n=24) | 200 mg intravenous bolus followed by an infusion (hydrocortisone 240 mg in 500 cc 0.9% saline) at a rate of 10 mg/hour | 7 | 920 mg | Severe |

| Mikami et al., 2007 [51] | Japan | SC, RCT | 31 | Prednisolone (n=15) | 40 mg/day, IV | 3 | 120 mg | Mixed |

| Fernandez-Serrano et al., 2011 [53] | Spain | SC, RCT | 55 | Methylprednisolone (n=23) | 200 mg loading bolus followed by 20 mg/12 hrs | 3 | 320 mg | Less severe |

| Wirz et al., 2016 [52] | Switzerland | MC, RCT | 726 | Prednisone (n=362) | 50 mg/day, oral | 7 | 350 mg | Mixed |

MC=multicenter; SC=single center; DB=double-blind; RCT=randomized control trial; IV=intravenous.

Efficacy of outcomes of the included studies.

| Study | Total number of patients | Mortality (death) corticosteroid/control | Length of hospital stay, corticosteroid/control | ICU admission or stay (days), corticosteroid/control | Duration of antibiotic treatment (days) corticosteroid/control | Time to clinical stability (days) corticosteroid/control | Hospital/ICU readmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wittermans et al., 2021 [41] | 401 | 4/7 | 4.5(95% CI, 4–5)/5(95% CI, 4.6–5.4) | 5(3%)/11(7%) | NA | NA | 20(10%)/9(5%) |

| Blum et al., 2015 [46] | 785 | 16(4%)/22(6%) | 6.0(6.0–7.0)/7.0(7.0–8.0) | 16(4%)/22(6%) | 9.0(7.0–11.0)/9.0(7.0–12.0) | 3.0(2.5–3.4)/4.4(4.0–5.0) | 32(9%)/28(8%) |

| Snijders et al., 2010 [47] | 213 | 6(5.8%)/6(5.9%) | 10.0±12.0/10.6±12.8 | NA | NA | 4.9±6.8/4.9±5.2 | NA |

| Torres et al., 2015 [48] | 120 | 6(10%)/9(15%) | 11(7.5–14)/10.5(8.0–15.0) | 5(3–8)/6(4–8) | NA | 4(3–6)/5(3–7) | NA |

| Mikami et al., 2007 [51] | 31 | 1/0 | 11.3±5.5/15.5±10.7 | NA | 8.5±3.2/12.3±5.5 | NA | NA |

| Meijvis et al., 2011 [49] | 304 | 8(5%)/8(5%) | 6.5(5.0–9.0)/7.5(5.3–11.5) | 7(5%)/10(7%) | NA | NA | 7(5%) 7(5%) |

| Confalonieri et al., 2005 [50] | 46 | 0/2 | 13(10–53)/21(3–72) | 10(4–3)/18(3–45) | NA | NA | NA |

| Wirz et al., 2016 [52] | 726 | 15/13 | N/A | 2(0.5%)/10(2,7%) | N/A | 3.4(1.5–8.5) | 3.6(2.0–5.9) |

| Fernandez-Serrano et al., 2011 [53] | 55 | 0/1 | 10(9–13)/12(9–18) | 6.5(5.5–9)/10.5(6.24–24.5) | N/A | 5(2–6)/7(3–10) | N/A |

All data are median (interquartile range) or mean ± SD.

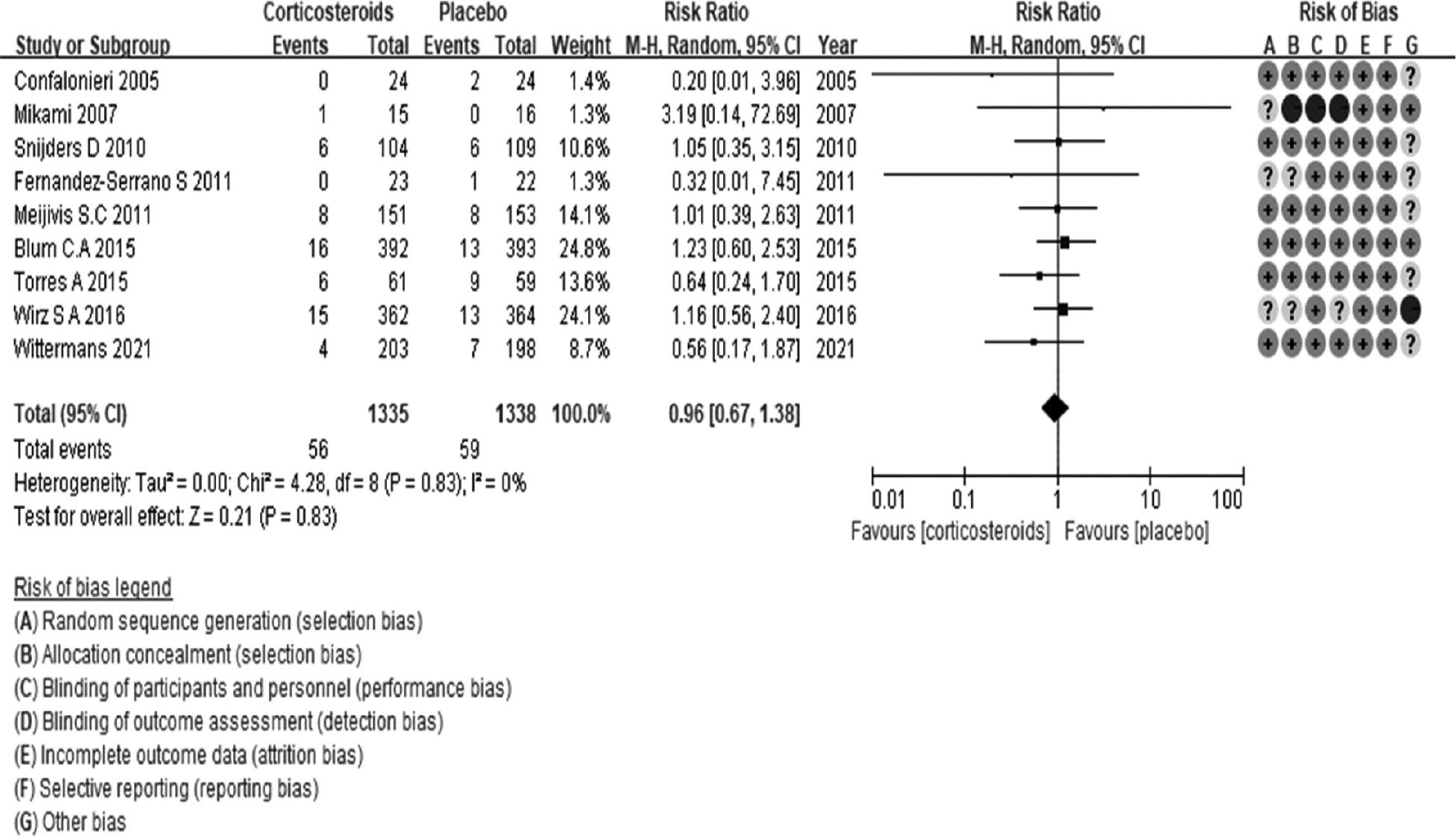

3.2 Primary outcome

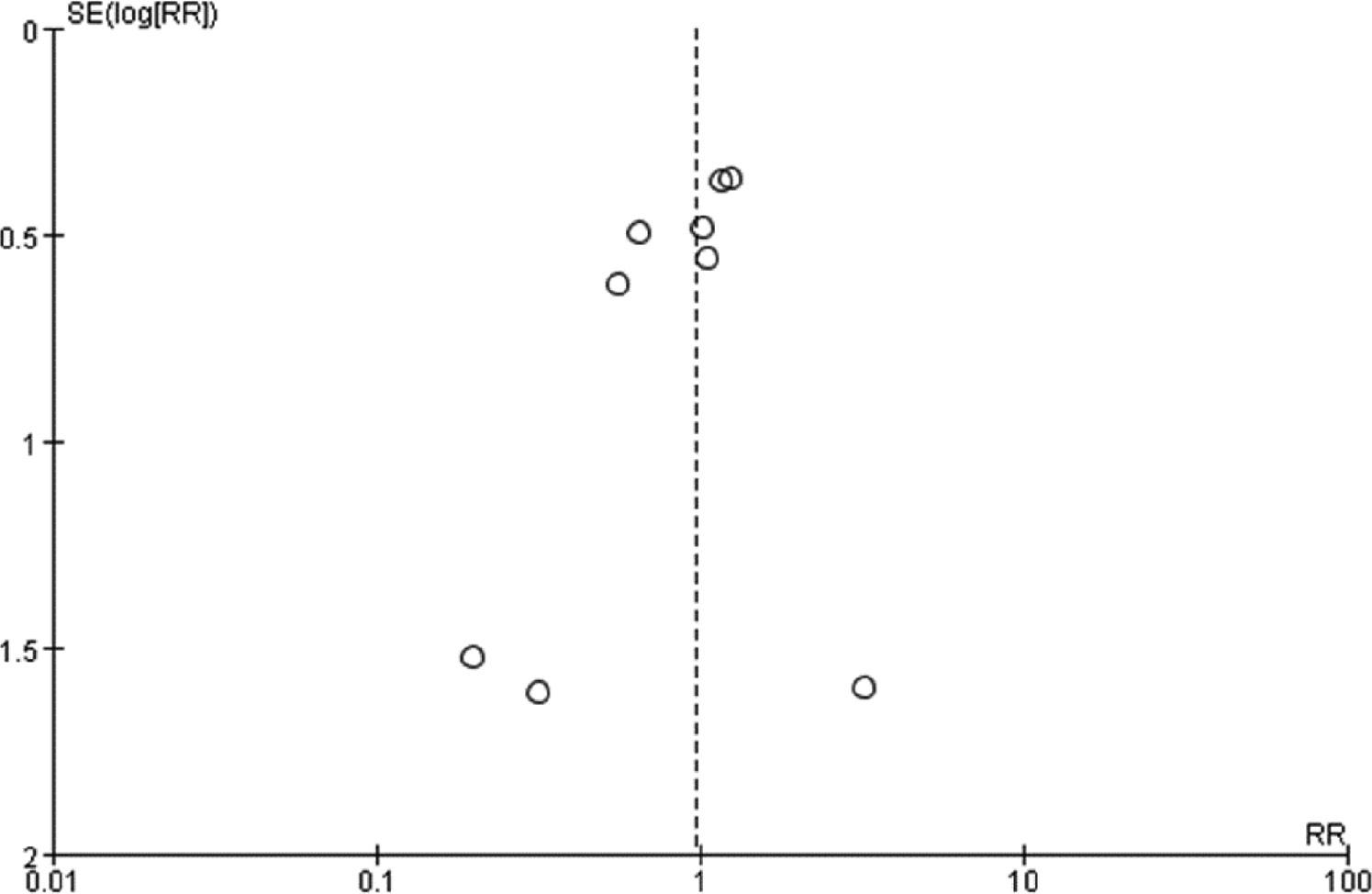

All nine trials with 2673 randomized patients were included in the analysis of mortality. The corticosteroid group comprised 1335 patients, 56 of whom died of CAP. In the placebo group, 59 mortality events were recorded in 1338 patients. Figure 1 illustrates the pooled results in a forest plot of mortality in patients with CAP from the random-effects model combining the RRs. The use of corticosteroids in patients with CAP was not associated with a significant decrease in mortality (RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.67–1.38, P=0.83). The grade quality was judged to be moderate, mainly because several studies had inadequate sample size and moderate risk of bias. Figure 2 displays the funnel plot of the included studies. The bar chart in Figure 3 illustrates how many people died in each study (in both corticosteroid and placebo groups).

Forest plot illustrating mortality of patients with CAP according to treatment arms.

The sizes of the squares denoting the point estimate in each study are proportional to the weight of the study. The diamonds represent the overall findings in each plot. All study names can be found in the cited references. df=degrees of freedom.

Funnel plot comparison of mortality of patients with CAP.

The dashed lines indicate the 95% CI. Each open circle represents a separate study. The middle dashed line indicates the overall effect. The unequal scatter indicates bias, which might be due to the small number of included studies. The absence of clustered studies at the bottom indicates small sample size.

3.3 Subgroup analyses and risk of bias

All subgroups showed no significant differences in mortality among patients with CAP ( Table 5 ). Two RCTs reported the effects of corticosteroids on the mortality of patients with severe CAP. The use of corticosteroids did not significantly decrease mortality rates in these patients (168 patients with 17 events; RR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.22–1.37) with no significant heterogeneity (I2 =0%). Similarly, in six RCTs whose patients presented with mixed CAP, corticosteroids did not significantly decrease mortality (2460 patients with 97 events; RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.73–1.58). This finding indicates no significant change in mortality with corticosteroids despite the severity of CAP. Similarly, treatment with corticosteroids for a short period of time (≤4 days) did not significantly decrease mortality in patients with CAP (901 patients with 44 events; RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.43–1.33). Regarding subgroup analysis of mortality in patients with severe and less severe CAP, 30-day mortality and mortality in patients with CAP who received a loading dose, we could not provide analysis figures for these subgroups because of the low number of studies. However, the findings from the analyzed subgroups indicated the insignificant effects of corticosteroids in decreasing mortality in patients with CAP. These subgroup results should be interpreted with caution because of the limited sample size and the potential bias inherent to subgroup analysis. The risk of bias relative to reports of mortality is shown in Table 6 . The selection and attrition biases were well controlled in most studies. However, imbalances were reported in patients with severe CAP [48, 50] and high levels of inflammation [53]. One study was judged to be of high quality; six studies were judged to be of fair quality, mainly because the adverse events were not prespecified, and because the outcome assessment was not specified; and two studies were judged to be of low quality, because they were not blinded, and the allocation of drugs was not concealed.

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis.

| Classification | Number of patients (studies) | Number of events/number in group | RR(95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid | Placebo | ||||

| Sample size | |||||

| ≤200 | 244(4) | 7/123 | 12/121 | 0.62(0.27–1.39) | .25 |

| >200 | 2429(5) | 49/1212 | 47/1217 | 1.05(0.75–1.55) | .81 |

| Type of mortality | |||||

| In-hospital | 873(4) | 18/439 | 26/434 | 0.69(0.39–1.22) | .20 |

| 30-day | 213(1) | 6/104 | 6/109 | 0.75(0.39–1.22) | .93 |

| Without explanation | 1587(4) | 32/792 | 27/795 | 1.18(0.72–1.94) | .50 |

| CAP severity | |||||

| Severe | 168(2) | 6/85 | 11/83 | 0.55(0.22–1.37) | .20 |

| Less severe | 45(1) | 0/23 | 1/25 | 0.32(0.01–7.45) | .48 |

| Mixed | 2460(6) | 50/1277 | 47/1233 | 1.07(0.73–1.58) | .72 |

| Cumulative dose | |||||

| ≤300 mg | 949(4) | 19/473 | 21/476 | 0.92(0.51, 1.67) | .79 |

| >300 mg | 1604(4) | 31/801 | 29/803 | 1.07(0.66, 1.74) | .79 |

| Use of loading dose | |||||

| Yes | 93(2) | 0/47 | 3/46 | 0.25(0.03–2.12) | .20 |

| No | 2580(7) | 56/1288 | 56/1292 | 1.00(0.70–1.44) | .99 |

| Duration of corticosteroid treatment | |||||

| ≤4 days | 781(4) | 13/392 | 16/389 | 0.82(0.41–1.64) | .58 |

| >4 days | 1892(5) | 43/943 | 43/949 | 1.00(0.67, 1.51) | .99 |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||||

| Multicenter | 2384(6) | 49/1193 | 52/1191 | 0.94(0.64–1.37) | .75 |

| Low-moderate risk of bias | 1871(6) | 40/935 | 45/936 | 0.89(0.59–1.34) | .58 |

| Confalonieri et al. [50] excluded | 2625(8) | 56/1311 | 57/1314 | 0.98(0.69–1.41) | .93 |

| Mikami et al. [51] excluded | 2642(8) | 55/1320 | 59/1322 | 0.95(0.66–1.36) | .81 |

| Snijders et al. [47] excluded | 2550(8) | 50/1321 | 53/1229 | 0.95(0.65–1.39) | .75 |

| Fernandez et al. [53] excluded | 2628(8) | 56/1312 | 58/1316 | 0.98(0.68–1.40) | .80 |

| Meijvis et al. [49] excluded | 2369(8) | 48/1184 | 51/1185 | 0.95(0.65–1.40) | .75 |

| Blum et al. [46] excluded | 1888(8) | 40/943 | 46/945 | 0.89(0.59–1.34) | .57 |

| Torres et al. [48] excluded | 2553(8) | 50/1274 | 50/1279 | 1.02(0.70–1.51) | .83 |

| Wirz et al. [52] excluded | 1947(8) | 41/973 | 46/974 | 0.91(0.60–1.37) | .79 |

| Wittermans et al. [41] excluded | 2272(8) | 52/1132 | 52/1140 | 1.01(0.70–1.47) | .84 |

Risk of bias summary of included studies.

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding to outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confalonieri et al. [50] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Mikami et al. [51] | Unclear | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Snijders et al. [47] | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Fernandez S et al. [53] | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Meijvis et al. [49] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Blum et al. [46] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Torres et al. [48] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

| Wirz et al. [52] | Unclear | Unclear risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Wittermans et al. [41] | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk |

3.4 Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed, and the studies are shown in sequential order of decreasing sensitivity in Table 5 . Significant differences were observed for two studies [47, 49], thus resulting in no significant mortality decrease. Although the study by Blum et al. [46] had a heavy weight of 24.8%, when that study was excluded, the pooled results showed no effect of corticosteroids in patients with CAP. Publication bias was not assessed, because of the limited (<10) number of studies included in this analysis.

3.5 Secondary outcomes

Because the data were reported inconsistently across studies (data were shown as median [interquartile range] or were not reported), we did not perform a synthesized analysis of other efficacy outcomes. Although a pooled outcome was lacking, nearly all included studies showed that corticosteroid treatment tended to decrease the lengths of hospital and ICU stays, the duration of antibiotic treatment and the time to clinical stability ( Table 4 ). Six trials reported data on the total adverse events that occurred during the study period. These adverse events included hyperglycemia [41, 47–49], superinfection [47] and empyema/pleural effusion [49]. Other adverse events recorded included falls resulting in fractures, cardiac decompensation (which was greater in the placebo groups), cardiac events, stroke and thromboembolic events [46], and gastric perforation [49]. Unspecified major complications were described in one study [50]. The GRADE quality was judged to range from very low to low. This index was not prespecified in the included studies, and the results were dominated by a study with unclear bias, so the findings should be interpreted with caution. Table 7 shows paired sample statistics for secondary outcomes.

Paired-samples statistics for secondary outcomes.

| Outcome | Mean | Standard deviation | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 [41, 46–52] | LOHS in corticosteroid group | 9.038 | 2.9947 | .002 |

| LOHS in placebo group | 11.138 | 5.1514 | ||

| Pair 2 [41, 46, 49, 52] | ICU admission in corticosteroid group | 7.50 | 6.028 | .041 |

| ICU admission in placebo groups | 11.25 | 7.890 | ||

| Pair 3 [47, 48, 50] | TTCS corticosteroid | 4.300 | 1.1269 | .047 |

| TTCS placebo | 5.433 | 1.3796 |

LOHS=length of hospital stay; TTCS=time taken to reach clinical stability; ICU=intensive care unit.

4. DISCUSSION

We conducted a review of multiple RCTs investigating the efficacy of corticosteroids for CAP. This is a novel review in that the search strategy did not segregate according to the severity of illness, the target population was not limited by age, and the results of the most recently published RCTs were included. A comparison of the incidence of primary outcomes between corticosteroids and placebo indicated no significant difference. In contrast, in the secondary outcomes, we identified a possibility that corticosteroids might decrease the length of hospital stay, time required to achieve clinical stability and duration of antibiotic treatment.

The finding that complementary corticosteroid use was not associated with a decreased mortality rate might have been due to late administration of corticosteroids and inadequate therapeutic doses, thus decreasing the effective serum concentration and the treatment response, given the decreased half-life of corticosteroids. Meijvis et al. [49] have highlighted that early administration of dexamethasone alters the immune response, on the basis of an accelerated return to normal concentrations of CRP and interleukin 6 observed in the dexamethasone group. This finding might have been due to the long half-life of dexamethasone; consequently, a gradual decrease in biological effects might be expected, thereby allowing for a gradual increase in the number of intracellular glucocorticoid receptors and recovery of the hypothalamic-adrenal axis.

An old study completed in 1993 was included by Huang et al. [54] in their meta-analysis [55] but was excluded in our study, because the type and principles of antibiotic administration, and other medical procedures used in the 1990s, greatly differ from current medical protocols. In addition, the definition of CAP was unclear in that study. Secondary outcomes, such as the length of hospital stay and ICU stay, duration of antibiotic treatment and time to clinical stability, in five included studies were shown as medians and interquartile ranges [46–48, 52, 53]. All these studies stated that their data had substantially skewed distributions. Pooled and converted data were not recommended by the Cochrane collaboration, because the results could be misleading. We also excluded three studies, although they reported the mortality rates associated with the complementary use of corticosteroids in CAP [56–58], because they did not explicitly specify or categorize the mortality rates within the different intervention groups, but reported overall mortality rates. To avoid the possible bias resulting from data conversion, we retrieved only qualitative descriptions with estimates, thus lending credibility to our results.

Corticosteroids may regulate inflammatory biomarkers, such that patients with CAP can be offered earlier effective treatment. Studies have analyzed the effects of inflammatory biomarkers to improve parameters in CAP. A study by Raess et al. explored how inflammatory biomarkers differed between prednisone and control groups [59]. In that study, corticosteroids decreased CRP levels, increased leukocyte and neutrophil counts, and had no effect on procalcitonin levels. A rebound effect in CRP levels was indicated after prednisone was stopped. In another study, acute administration of methylprednisolone was associated with less treatment failure and a lower inflammatory response [48]. Controversially, a study comparing inflammatory cytokines in patients with CAP has argued that the imbalance between the high inflammatory state and low cortisol levels did not predict treatment response to corticosteroids. Popovic et al. have shown that corticosteroids do not decrease copeptin levels to a greater extent than placebo over time. In addition, the effect of corticosteroids on neurons appears to be present only in patients pre-treated with corticosteroids before inflammation peaks [60]. In contrast, several studies have highlighted a faster decrease in blood interleukin-6 and CRP levels in patients with CAP administered corticosteroids [50, 53, 59]. Similarly, a methylprednisolone regimen in children with severe CAP has shown positive clinical utility in decreasing the duration of fever and the levels of CRP by 50% [61]. A decrease in CRP levels supports that restraining systemic inflammation is an imperative priority in the management of patients with CAP. Cortisol is another biomarker that might be useful in CAP prognostication, because it is the predominant compound secreted by the adrenal cortex and is an important endogenous regulator of inflammation. A high serum cortisol concentration at hospital admission is associated with adverse outcomes resulting in uneventful recovery in patients with CAP [62]. In contrast, Blum et al. have argued that treatment decisions for/against adjunctive corticosteroid use in CAP should not be made on the basis of cortisol values or cosyntropin testing results, because neither baseline nor stimulated cortisol after low dose cosyntropin testing is predictive of glucocorticoid responsiveness in mild to moderate CAP [63]. Hence, given the conflicting biomarker values in CAP, biomarker values should not be used in isolation. Instead, they should be considered in conjunction with the patients’ clinical presentation and history, and imaging and other laboratory results, as well as medical practitioners’ clinical experience and judgement.

More recently, a significant decrease in median length of stay and ICU admission rate in adult patients hospitalized with CAP has been reported in an RCT (n=401) testing a 4-day continuous dose of oral dexamethasone (6 mg/day) versus placebo [41]. In another study (n=726) including 19% patients with diabetes mellitus, the time to reach clinical stability decreased in patients with or without diabetes [52, 64]. These observations indicate the validity and benefit of complementary prednisone administration for patients with diabetes or hyperglycemia at hospital admission. In contrast, Ceccato et al. have concluded that the glucocorticosteroid and macrolide combination has no statistically significant association with clinical outcomes, as compared with other treatment combinations, in patients with severe CAP and a high inflammatory response, after accounting for potential confounders [56]. Four meta-analyses have shown that complementary systematic use of corticosteroids is safe and beneficial for patients hospitalized with CAP [37, 38, 54, 65].

Therapeutic doses of corticosteroids vary greatly, as do adverse effects. Patients require education regarding what to expect with short- or long-term corticosteroid use. Other pharmacological therapies, such as gastric acid suppression, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and opportunistic infection prophylaxis, may be necessary to counteract corticosteroid-associated adverse effects [66–69]. Providers must weigh the risks versus benefits of corticosteroid use, and use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible to avoid or minimize severe corticosteroid-induced toxicity.

Another factor that must be considered in patients with CAP is the recognized risk of Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [70]. The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 resemble those of CAP [71]. Hence, several observational, retrospective and comparative studies have been performed to distinguish the clinical characteristics of CAP and COVID-19 [71–77]. In one study, patients with COVID-19 have been found to show higher copeptin levels and lower leucocyte counts than patients with CAP [71]. This finding highlights that biomarkers might serve as predictors for differentiating between COVID-19 and CAP. Other clinical manifestations, such as diarrhea, and lymphocyte and eosinophil counts, can distinguish CAP from COVID-19 [75]. In addition, the use of artificial intelligence analysis of chest computed tomography (CT) scans has been proposed to accurately detect and differentiate CAP from COVID-19; patients with COVID-19 exhibit more extensive radiographic involvement [78–81]. CT images are accurate and can accelerate diagnosis. Lung ultrasound has also been used distinguish the sonographic features between COVID-19 and CAP [82]. Of note, guidelines for the treatment of adults with CAP amid the COVID-19 pandemic have been established [83]. Interpretations of the guidelines’ application to evaluation and treatment, including diagnostic testing, determination of site of care, selection of initial empiric antibiotic therapy, and subsequent management decisions, have been explained [84]. COVID-19 preventive measures and personal hygiene have been found to be effective measures in preventing the spread of CAP. A multicenter study in Japan has revealed a decrease in CAP hospitalizations amid the COVID-19 pandemic [85]. In summary, an in-depth understanding of lung-tissue-based immunity may lead to improved diagnostic and prognostic procedures in CAP. Novel treatment strategies aimed at decreasing the disease burden, avoiding the systemic manifestations of infection, and decreasing mortality and morbidity, are imperative.

This systematic review has several limitations. First, the severity of illness was not consistent across the included studies. Second, the number of patients with CAP was low, thus suggesting that the results might not be stabilized. Finally, most studies did not report related data, thus emphasizing the need for additional studies.

5. CONCLUSION

We performed the latest review assessing the efficacy of corticosteroids for CAP, including up-to-date clinical trials in our search scope. Our study suggests that complementary corticosteroid treatment is not significantly associated with a decrease in mortality rates in patients with CAP. Analysis of secondary outcomes suggested that the adjunctive use of corticosteroids may be effective in shortening the time required to reach clinical stability, length of hospital/ICU stay, and duration of antibiotic treatment. Because of the low number of patients in our study, more studies are needed to confirm this result.