Introduction

On 6 April 2023, Tunisian President Kais Said denounced the conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), urging Tunisians to ‘rely on ourselves’. The comments came after more than year into Said’s iteration of one-man rule, a freestyle exercise through which he vowed to endeavour to ‘restore the will of the Tunisian people’. Yet, with a balance of payments crisis looming large and a disgruntled public facing shortages of basic staples, the Tunisian government has yet again sought a bailout from the IMF. The content of the so-called rescue package, while vague, has induced a renewed wave of discontent among critical observers wary of the Fund’s plans for economic restructuring.

In the midst of this economic and political angst, many have turned their attention to the nation’s largest labour syndicate, the Tunisian General Labour Union (Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail, UGTT), as a likely source of opposition to continued neoliberal restructuring. With decades of experience in organising labour and a significant base primarily concentrated in the public sector, the UGTT has been a pivotal force in the Tunisian political landscape since the 1940s. It predates the establishment of an independent state, to which the union’s anti-colonial struggle contributed. Having endured both Habib Bourguiba and Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali’s respective attempts to co-opt it, the UGTT has maintained its radical clout and emerged as a key player in the transitional process.

While Tunisians’ ability to voice discontent at IMF-piloted reforms was constrained by authoritarian repression prior to the 2010–2011 uprising, the process of ‘democratisation’ has emboldened Tunisians to intervene in economic issues and voice their popular will. Surface-level democratisation, however, did not sway Tunisia from its neoliberal path, as post-revolutionary governments continued to solicit the IMF’s support for its political transition. The IMF – with its legacy of austerity policies – fostered the post-Ben Ali era of continuous protests. Meanwhile, the UGTT became a central oppositional force to the dictates of the IMF, mobilising its base and becoming increasingly politicised. Against the backdrop of the current IMF–government talks on a new loan, this briefing: reflects on the troubled history between the IMF and Tunisia in the post-uprising era, focusing on the two major loans – the Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) and the Extended Fund Facility (EFF); and assesses the UGTT’s post-2010 role in negotiating and resisting these loans, drawing on its public statements as well as interviews with UGTT economic advisors and civil society activists conducted in February 2022.

The dawn of a new IMF? Tunisia–IMF relations in the post-uprising era

Structural adjustments? That was before my time. I have no idea what it is. We don’t do that any more [sic]. No, seriously, you have to realise that we have changed the way in which we offer our financial support. (Christine Lagarde, quoted in Kentikelenis, Stubbs, and King 2016, 544)

In the aftermath of the uprising, the IMF found itself forced to reckon with its past policies, having facilitated Ben Ali’s wealth hoarding and the immiseration of millions. The IMF was seen as ‘complacent in their acceptance of government narratives … hardly surprising given that the Tunisian regime was eager to demonstrate its conformity with the IFIs’ own Washington consensus agenda’ (Murphy 2013, 43). In statements delivered by its leadership, the Fund vowed to imbed ‘social dimensions’ into its future economic planning vision, signalling the beginning of a rejuvenated engagement strategy with Tunisia. The then-IMF Managing Director, Christine Lagarde, conceded that the Fund:

had learned some important lessons from the Arab Spring. While the top-line economic numbers – on growth, for example – often looked good, too many people were being left out … [The IMF was] not paying enough attention to how the fruits of economic growth were being shared. (Lagarde 2011, para. 7)

In the summer of 2013, the IMF Executive Board approved a US$1.74 billion SBA for Tunisia following a Letter of Intent (LOI) sent by the then-government and the Central Bank of Tunisia. The money was to be disbursed over a 24-month period, with tranche payments dependent on eight programme reviews conducted by the IMF over this time. The arrangement aimed to ‘ease pressure’ on the Tunisian government and ‘energise the economy’ through ‘restoring fiscal space, rebuilding foreign reserves, reducing banking sector vulnerabilities and fostering more inclusive growth’, according to a 2013 IMF memo (IMF 2013).

This deal would become mired in controversy and ignite a wave of criticisms and protests, not only due to its remarkable similarity to previous packages advanced by the IMF (Hanieh 2015), but also because the secrecy surrounding it prompted questions about Tunisia’s sovereignty and the legitimacy of its freshly minted democracy.

These fears quickly became a reality when the 2014 Finance Bill was unveiled. In line with IMF loan obligations, the bill contained austerity measures, including plans for wage cuts and subsidy reform in the name of fiscal consolidation. In keeping with the IMF’s new ‘socially conscious’ discourse, the cuts to subsidies were justified by the implementation of targeted welfare for the neediest of the population in the form of vaguely defined ‘social safety nets’ or ‘household support programmes’. There is little novelty to this approach, which has been adopted by the IMF since the 1990s, a testament to how little the Fund has evolved in its lending practices. In response, Tunisian activists highlighted how ill-suited such a strategy was in country with no adequate targeting and identification mechanisms, and little means to establish such an infrastructure, warning that the approach would inevitably impoverish many people that may find themselves excluded from targeted welfare. Instead of listening to its ‘valued stakeholders’, the IMF responded by publicly refuting austerity criticism from civil society, diverting blame for the country’s meagre economic performance to its ‘model of state patronage’ (IMF 2018c, para. 2).

The unpopularity of the SBA would not sway subsequent Tunisian governments from soliciting further assistance from the IMF. A 2016 LOI sent by Tunisian authorities to the Fund explained that – despite the SBA’s success in achieving some macroeconomic stability – structural issues persisted, including stubbornly high unemployment and a hefty wage bill burdening government expenditure (IMF 2016). Later in 2016, the IMF conducted a mission to Tunisia to discuss the prospect of a four-year arrangement under the Fund’s EFF, amounting to about US$2.8 billion, in support of Tunisia’s economic reform project. With the approval of the EFF, the Tunisian government pursued fiscal consolidation more aggressively, in its quest to downsize its ‘inflated’ public sector and minimise subsidy spending. The 2018 and the 2019 Finance Bills following the EFF enshrined these objectives, despite the criticism that the SBA garnered back in 2013 remaining largely unaddressed by both the state and its creditor.

Foreign debt versus organised labour

In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, UGTT’s leadership affirmed that the union ‘does not have hostile, gratuitous prejudices against the IMF’ (former UGTT Secretary General Houcine Abassi, quoted in Yousfi 2019, 200) and generally maintained a neutral tone toward the Fund. The UGTT’s then-Director of Research and Documentation went as far as welcoming the involvement of international financial institutions, saying that ‘we are aware that the country cannot survive outside of the global system, but we try to guide policy. We told the World Bank, “You supported Ben Ali. Now you have to demonstrate, via pilot development projects in disadvantaged regions, your desire to support democracy”’ (Yousfi 2019, 203). Exploiting democratisation as a public good worthy of investment is a prevalent trend within post-2010 political elite circles (Erol 2020) and is the same line of argument put forward by the Tunisian state in its LOIs requesting assistance from the IMF (IMF 2014; 2016).

The UGTT therefore assumed a stance similar to that of mainstream political forces on possible loans from international financial institutions, arguably overlooking grassroots voices which as early as 2012 had sounded the alarm about the conditionalities which would be attached to such loans. The Magaloulnesh campaign led one of these early efforts, with respect to the post-2010 Central Banking Law, written in consultation with the IMF, which attempted to shield monetary policy from democratic oversight. According to an activist from the now-dormant movement, the UGTT was ‘entirely absent’ in these mobilisations and the issue of central bank independence was ‘not on its radar’ in 2013 (interview, February 2022).

At the same time, in its first post-uprising national congress the UGTT adopted a set of resolutions decrying privatisation, international loans and corruption (Beinin 2015, 132). But UGTT observers remained cautious about conceiving of the union as a ‘revolutionary political formation. [For] it remains a trade union with a bureaucratic structure and a fundamentally reformist goal – to improve wages and working conditions within the framework of whatever regime exists’ (Beinin 2015, 106). However, the years following the adoption of the EFF and SBA saw relations between the UGTT and IMF characterised by futile collaborations which left the UGTT increasingly frustrated, and which led it to start espousing increasingly combative stances towards the IMF and leverage the threat of several general strikes to decelerate or entirely halt its restructuring plans.

In the spirit of ‘guiding policy’, the UGTT and the IMF have met frequently during the Fund’s official missions to Tunisia within the context of its Article IV consultations on the EFF and SBA. A senior economic advisor for the UGTT explained that the union does ‘not seek out [meetings with] the IMF. IMF delegates come to Tunisia – as guests – and the union engages in discussions with them as it would with any international organization … It is the IMF that seeks us out.’ During these technical meetings, the IMF delegates ‘make an effort to hear us [UGTT] out; they are interested in better understanding the constraints on our economy’ (interview, February 2022). These consultations take the form of a general dialogue, during which the two sides exchange views in search of solutions to the economic crisis. While the UGTT strives toward neutralising the IMF and limiting its impact on the negotiations, the IMF seeks to appear to have an open mind and to agree with the union on diagnosing the economic situation, albeit without adopting the same solutions (El-Medini 2019).

The policy impasse between the two parties has meant that the meetings are often fraught, specifically with respect to public sector wages, on which the two parties have diametrically opposing positions. The UGTT has thus claimed that its economic vision is rarely reflected in the IMF’s reform packages, arguing that the Fund ‘remains allergic to minimum wage, social protections’ (interview, February 2022) and other demands behind which the UGTT has historically rallied. Furthermore, the union argues, the IMF’s ‘unhealthy fixation’ on macroeconomic stabilisation at the expense of the general wellbeing of Tunisians has led to the failure of its post-2010 reform plans:

We are cognisant of the importance of macroeconomic stabilisation, but this has to be conducted within a context of better public services, with a ‘human’ element in mind, all while preserving the liberty of Tunisians … Taking the current situation as an example: we are told we need to reduce the budget deficit. This is a reasonable request, but it is not an objective in and of itself. The objectives of development are not purely concerned with macroeconomic stability, they are equally concerned with the wellbeing of the average Tunisian – this is the fundamental difference [between the UGTT and IMF]. (interview, February 2022)

The UGTT placed the blame for the country’s crisis-ridden economy on the unsustainable rise in its debt-to-GDP ratio, which in 2016 and 2018 soared to 64% and 71%, respectively (IMF 2022), compared to pre-revolutionary figures which hovered around 41% (Chandoul 2018).

Other civil society forces, namely the anti-austerity and youth-led Fesh Nestannaw campaign, have also questioned the long-term durability of Tunisia’s borrowing practices. In response, the IMF has suggested a reform scenario aimed at bringing back the debt to sustainable levels. Showing little change from its pre-2010 approach, the Fund devised a framework reliant on more austerity measures, including reducing the public wage bill (IMF 2018a; 2018b), which the union has consistently and categorically opposed. In a meeting bringing together different trade union representatives held in Washington DC, Taboubi criticised the IMF for turning a blind eye to matters of fiscal justice (with fiscal avoidance amounting to 2% of Tunisia’s GDP) and the increasing indebtedness of the private sector, and its fixation on reducing public sector wages without full cognisance of their devastating effects (El-Medini 2019, 181).

General strikes between 2016 and 2019

With the IMF’s continued fixation on the public wage bill, the UGTT shifted to a more aggressive strategy as its membership’s very survival was at stake. This shift was especially remarkable toward the end of 2016, when IMF–UGTT relations became noticeably contentious, and the union began adopting a more antagonistic stance. Then-Secretary General Houcine Abassi accused the IMF of ‘iizduaj khitabi (double discourse), alleging that the IMF had adopted different positions when meeting with different stakeholders – a sentiment echoed by other UGTT affiliates who saw in the IMF’s ‘hypocrisy’ a danger to the organisation’s integrity and public image (Trabelsi 2022). Abassi’s statement coincided with the 2017 Finance Bill, which proposed an increase in prices on basic goods, a 1% hike in value-added tax, and a decrease in public sector employment. In response, the UGTT threatened a nationwide general strike on 8 December 2016. Alarmed by the potential disruption, the consequences of which could be calamitous to the country’s fragile economy, the then-president intervened and offered concessions. Reassured by the promise of a ‘long-overdue’ increases of wages frozen since 2013, the UGTT called off the strike. Mere days later, the IMF postponed the disbursement of the second tranche of the EFF due to a lack of progress on public employment reforms.

Prior to the 2019 Finance Bill, the government was also under pressure as the IMF pushed for budget deficit and wage bill reductions, on which the release of funding tranches was made conditional. This led to more ferocious resistance from the UGTT, which had hoped for wage increases to match mounting inflation. Between a government cornered by its creditors and an uncompromising trade union, negotiations failed to reach an agreement. As a result, the UGTT led a national public sector strike on 22 November 2018 of roughly 650,000 public sector employees – its largest display of collective action since 2013. The union’s Secretary General accused the government of being entirely beholden to its creditors, declaring that ‘the sovereign decision is no longer at the hand of the government, it has shifted to the hands of the IMF’ (El-Medini 2019, 178).1 The strike championed the slogan alsiyada qabl alziyada (sovereignty before [wage] increases) in a bold move reflecting the expanding role of the UGTT as a custodian of national sovereignty in face of crippling foreign indebtedness.

In response to the government’s refusal to meet its demands, the UGTT organised a second national strike on 17 January 2019. As a result of these consecutive strikes, then-Prime Minister Chahed signed an agreement in February 2019 that increased public sector wages – a move hailed as ‘a victory for the Tunisian trade union movement against the dictates of the IMF’ (Taboubi 2019, para. 1). Expecting nothing short of full compliance from the Tunisian authorities, the IMF signalled its disapproval by once again delaying the payment of a tranche of the loan (Erol 2020).

To strike or not to strike?

The UGTT’s engagement with post-revolutionary IMF loan conditionality has not been entirely without controversy. Their general strike strategy, in particular, has been met with resistance from sceptics who saw the union’s actions as reinforcing the economic inertia debilitating the country’s economy and impoverishing its citizens (interview, February 2022). In response, the UGTT has justified its strike method as ‘an important dimension to Tunisia’s social dialogue’, and its leaders have stressed that the union typically exhausts all negotiations before deciding on this action: ‘People don’t see the effort that [we] exert during the pre-strike negotiation phase, they only see the strikes. They don’t see the arbitrary sackings, the abuses, the low wages’ (interview, February 2022). The UGTT has also alluded to the compromises it has made, such as during the critical National Dialogue year2 when it abstained from demanding wage increases to focus on ensuring political stability. The union has maintained that IMF-imposed public wage reduction posed a fundamental threat to the constitutional rights of Tunisian workers that warranted collective action on a national scale. At the same time, the UGTT has called off a handful of planned strikes between 2013 and 2019, such as the 2016 general strike, once consensus was reached. `

Nevertheless, this approach has not always been successful given the oft-quarrelsome relationship between the UGTT and post-2010 governments. Perhaps nowhere was this more evident than in 2018 when – during Prime Minister Chahed’s tenure – the UGTT cancelled a general strike scheduled for 18 October after the government agreed to an increase in public sector wages and to halt the sale of certain state-owned enterprises. In exchange, the UGTT was to refrain from obstructing the 2019 Finance Bill. To the trade union’s surprise, the government backtracked on part of the agreement by attempting to sell the National Board of Tobacco and Matches (RNTA). The RNTA’s union, a UGTT subsidiary, organised a walk-out in protest at the IMF-steered plan for privatisation (Ben Gharbia 2017). Earlier that year, following IMF advice to liberalise interest rates and open its foreign exchange market to attract foreign direct investment, the Central Bank of Tunisia increased interest rates to 6.75%. Critical observers deemed the surge ill-timed for coinciding not only with a 7.7% inflation rate, but also a consumption tax increase imposed in May (Capelli 2018). Secretary General Taboubi agreed, stating that ‘such a measure has negative repercussions on investment and growth, which will exacerbate the current economic crisis and further deteriorate the already dilapidated purchasing power of workers’ (ITUC, 2018, para. 4). The combination of cumulative austerity policies and ‘bad faith’ negotiations on the government’s part led to the UGTT calling for a nationwide strike in November, its ‘last resort’ (interview, February 2022).

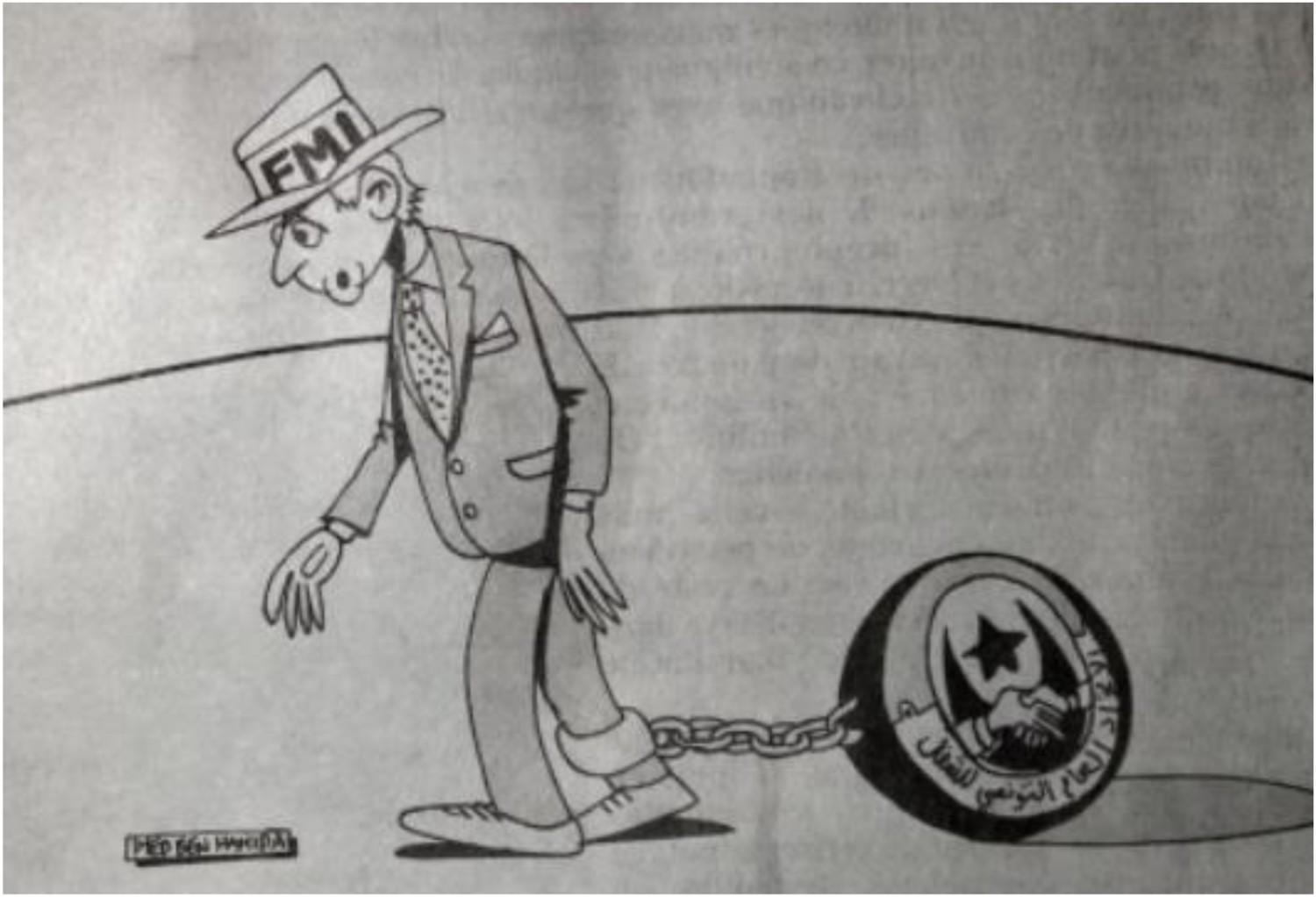

The UGTT has levied its power of collective action not solely in response to economic grievances, but also in relation to political demands. The 2013 political crisis, the product of the assassinations of two left-wing politicians, is a prime example of this. The UGTT called for a nationwide strike to grieve the assassinations of Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi and denounce the then-government for its alleged complicity in violence against left-wing figures. The widening of the UGTT’s mandate is, some observers argue, the transformation of the UGTT into a fully fledged political opposition ‘force’ (hezb mo’aredh), even though the UGTT, in the words of its leadership, has always striven to maintain its ‘independence’ from political parties. The point remains that to observers – both within and outside the country – the UGTT seems to be the only structured power willing and able to stand up to the IMF; a sentiment echoed in the wider Tunisian political discourse and perhaps best illustrated in the caricature in Figure 1 of the IMF shackled by the ‘powerful’ UGTT.

Caricature by Imed Ben Hamida portraying the IMF shackled by the UGTT; originally published in Tunis-Hebdo (Ben Hamida 2022) (published with the kind permission of the artist).

It is worth noting, however, that the UGTT only began to systematically challenge the IMF’s austerity requirements when these constituted a direct assault on its constituency. For the trade union, public sector employment and wages constituted the thorniest issues which it fiercely championed between 2013 and 2019, employing the general strike as its primary weapon of defence. The success of general strikes (or threats thereof) during these six years materialised in the wage increase agreements secured by the union and which the IMF responded to with loan payment postponements, signalling its discontent with Tunisia’s noncompliance. To this day, the public sector wage bill remains one of the biggest points of contention between Tunisia and its creditor, with the UGTT persistent in shielding its base from wage austerity and the IMF steadfast in its policy advice. Despite the UGTT’s efforts, Tunisians continue to experience economic adversities, as the country grapples with mounting indebtedness and soaring unemployment rates amid IMF-piloted restructuring. The resultant wave of subsidy reforms and price increases has left many bracing in anticipation of more financial hardships. The IMF has also made public services, such as energy, an object of its intervention, with the Tunisian Observatory for the Economy warning of the envisioned reforms’ deleterious impacts on overall quality of life (Ben Sik Ali 2023).

While the UGTT has been limited in its ability to halt these efforts, it has recognised the need to broaden its base and engage with nascent actors whose struggles against austerity have become a defining feature of the post-uprising era. Cognisant of the need to broaden its base, yet making no ideological compromises, the UGTT has recently shifted towards collaborating on issues such as fiscal justice. The decision to focus on progressive tax reform is anything but arbitrary, for ‘there is no consensus among civil society actors and citizens in general about privatisation’ (interview, February 2022), whereas fiscal justice presents an opportunity to rally many Tunisians across the political spectrum.

‘New’ IMF loan: where to now?

In Said’s Tunisia, the UGTT’s stance on the IMF’s vision for reform had wavered little. At the onset of talks with the Fund about a new loan, the UGTT, riding the wave of yet another successful public sector strike in June 2022, demanded guarantees on state-owned enterprises and reiterated the same grievances from years ago. But if the UGTT is starting to sound like a broken record, it is only because the IMF has regurgitated the same language of tackling fiscal imbalances and the public sector wage bill, urging the government to abolish subsidies in favour of ill-designed cash transfers for the country’s most vulnerable people. The impasse continues in a seemingly never-ending cycle with an economy replete with calamities and a difficult-to-predict political landscape.