Introduction

Since its 2013 debut on the South African political stage, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party has confounded scholars regarding the nature of its ideological positionings, its realpolitik, and the profile of its supporters. Using University of Johannesburg (UJ) election survey data from the 2021 local government elections, this intervention seeks to cast light on EFF voter characteristics, including an analysis of previous party support. The picture painted is one of a party constituted of a relatively well-educated, and, to a lesser degree, relatively well-off support base that also evinces some fluidity vis-à-vis loyalty to the EFF.

While discourse around the EFF often touches upon the party’s ideological opaqueness, policy vacillations or scandals among its leadership, the present data reveal a party that acts as a repository for a hopeful, young and radical demographic, but also serves as a ‘gateway party’, leading away from the African National Congress (ANC) and towards support for smaller parties, on both the left and the right of South Africa’s political spectrum.

Positioning itself as a radical leftist alternative to the ANC, the EFF offered an urgent critique to the neoliberal development model of the ruling party in South Africa (Adams 2018; Horwitz 2016, 65; Mubecua and Mlambo 2021; Mukhudwana 2021; Thwala 2018; Yende 2021). Appealing to the unemployed and disenfranchised – those ‘left out of the social contract’ (Adams 2018) – the party enjoyed quick initial growth upon its formation in 2013 (Nieftagodien 2015). Scholars (e.g. Roberts 2019) confirmed black youth, unemployed and poor, as the party’s ‘core constituencies’. The party’s sartorial repertoire (including red berets appropriated from the Black Panther Movement, and workers’/housekeepers’ overalls to signal solidarity with labour [Nieftagodien 2015] and an intent to work hard [Mukhudwana 2021]), vociferous theatrics in parliament, and populist rhetoric (Mbete 2015) all constituted an effective performance in decolonial political branding (Mukhudwana 2021), attracting a militant, often economically marginalised and youthful support base. In fact, when considering supporters, Paret (2016) found that people who had previously engaged in public protest are more likely to support the EFF than other parties.

Notwithstanding its early successes, the EFF has also been described as burdened with ideological contradictions (Nieftagodien 2015) and lacking political substance. Funding opaqueness, sexism and a programme generally perceived as ‘toxic’ has hampered its traction (Gibson and Gouws 2022; Roberts 2019; Schulz-Herzenberg and Southall 2019). The leftist academe also criticised the party for exploiting events such as the Marikana massacre and the #feesmustfall movement (Mbete 2015), while, more recently, others have questioned whether the EFF is ‘correctly described as leftist’, because at times it appears to lean towards right-wing ethnic nationalism (Mukhudwana 2021). As such, despite Paret (2016) identifying a sample of EFF supporters in the period between the 2014 and 2016 elections as ‘especially loyal’, the consistency of the party’s support is contentious (Mbete 2015).

In addition to its (at the very least rhetorical) solidarity with the economically marginalised, the EFF’s youthful profile is well established, the party itself having been grafted from the ANC’s youth league (Runciman, Bekker, and Maggott 2019). Having cast itself as a representative of the concerns of young South Africans – most of whom are poor, and poorly served by the state – the party is meant to appeal to the 11 million South Africans (about a fifth of the population) living on less than US$1.90 (R27) per day (UNDP 2022), and suffering an education system generally regarded as among the worst in the world (OECD 2019).

In the wake of the 2019 elections, the EFF came to be seen as a party with ‘staying power’, with a (small but) loyal voter base providing political ‘endurance’ and ‘entrenchment’ (Roberts 2019, 98, 108, 112). Post 2021, given its rhetorical and ideological positioning, relatively youthful leadership, and purchase on South African student politics, the EFF’s support base appears likely to remain youthful. However, this briefing suggests that the party’s youthful profile might be further nuanced to reveal a support base that is neither loyal nor proto-typically marginalised.

About the data source

The findings here are based on data from the UJ 2021 Local Government Elections Combined Dataset (hereafter ‘Elections Dataset’). This dataset is the outcome of a telephonic survey of voters and non-voters carried out between 2 and 16 November 2021, starting the day after the elections and ending less than three weeks later. For a discussion of the data and enumeration methods, see Runciman, Bekker and Mbeche (2021).

The telephone survey (conducted as computer-assisted telephone interviews) included 12 sociodemographic, biographical and geographical questions, three questions on protest history, five on voting, and two questions on political opinions. The poll included the questions ‘Which political party did you vote for today as your ward councillor?’ and ‘Which political party did you vote for today on the PR ballot?’ (PR referring to Proportional Representation), in both cases offering as options the four most prominent parties as well as ‘another party’ and ‘refuse to say’. The survey realised a total of 3905 responses; thus, while the sample is reassuringly large, polling biases cannot be discounted.

Findings

Regarding the ‘youth vote’ in the 2021 local government election (LGE) in South Africa, a related study saw the EFF capturing 12% of the vote, with the ANC winning 59%, the Democratic Alliance (DA) 11%, and the remaining 18% distributed among smaller parties. The rest of this briefing reports on the noteworthy trends of the youth as relatively well educated, relatively well off and relatively fluid.

Relatively well educated

This brief’s most overwhelming and perhaps unexpected finding was that the supporters of the EFF appear to be better educated than supporters of the DA and ANC, as adjudged by the proportion of voters holding a post-matric qualification, given the Elections Dataset. In a country where less than 8% of adults have a qualification past Grade 12 (OECD 2019), it is expected that a modest proportion of political parties’ support will be drawn from people with tertiary (denoted ‘post-matric’) qualifications. However, in the Elections Dataset, almost a quarter of those supporting the EFF self-report having a post-matric qualification, more than five percentage points higher than those supporting the DA (the next-best-educated party among the largest three parties).

Table 1 presents party support by levels of educational attainment. Apart from confirming the relatively high mean of the educational attainment of EFF supporters, vis-à-vis the three largest parties, it also illustrates that the EFF receives the lowest proportion of its votes from those whose highest education achievement is below Grade 12 (‘matric’). This profile is ostensibly related to the party’s strong purchase on South African university politics, where, in early 2022, the party held more than half of the elected student council chairperson positions in the country’s 26 public universities.

Relatively well off

The brief’s next finding is that EFF voters come from both rich and poor (relatively speaking) households, with a notable proportion from the highest income-earning category. Table 2 presents the Elections Dataset by support for the three largest parties, dividing party support into income categories. While raw numbers would show the ANC dominating in all categories, within-party profiles show the (centre-right) DA support base coming from a richer demographic overall. What is arguably most surprising here is the contrast between the ANC and the EFF: the ANC received 7% of its support from the highest-earning group, while the EFF received almost double that, at 13%.

Percentage of within-party support by income category (rand per month).

| Less than 2500 | 2501–5000 | 5001–10,000 | More than 10,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African National Congress | 68 | 12 | 13 | 7 |

| Democratic Alliance | 44 | 16 | 12 | 28 |

| Economic Freedom Fighters | 58 | 16 | 13 | 13 |

| Other | 45 | 13 | 12 | 30 |

Stated differently, while it is no surprise that the DA’s support skews towards a relatively wealthy profile (i.e. historically white – white people still hold disproportionate wealth), the EFF’s profile invites reflection. Perhaps its relatively better-off support base is related to the EFF’s popularity among students, considering that those having recently left universities are more likely, all else being equal, than their contemporaries to be employed. However, might the phenomenon of the EFF appealing to a wealthy demographic suggest rather that the party has found favour among a middle-class support base, or might one offer yet another, more nuanced interpretation – perhaps tied to the party’s prominence among students or to its role in offering people a way ‘out of’ the ANC?

Fluidity: the EFF as a ‘gateway party’?

The alluvial flow (or Sankey) diagram in Figure 1 visualises the coursing of support towards and away from the EFF at elections since 2016 (based solely on responses in the Elections Dataset). First, the flows confirm recent findings (Bekker, Runciman and Roberts 2022) about electoral behaviour in South Africa in general: that there is a non-negligible amount of fluidity between voting and abstention, but also a notable amount of switching of support from one party to another across elections.

Alluvial flow diagram of support for the Economic Freedom Fighters at the 2016, 2019 and 2021 elections in South Africa. Source: 2021 University of Johannesburg Elections Dataset.

Secondly, EFF-related support appears to exemplify voter fluidity in contemporary South Africa. Within the sample, the party lost a third of its 2016 voters at the 2019 elections, and more than half of its 2019 support came from people who voted for another party in 2016 (or from first-time voters). Considering the passage from 2019 to 2021, the party lost half of its support (although a sizable proportion of its 2019 voters chose not to disclose their voting actions in 2021). Regarding the 2021 election, about half of the party’s support came either from people who had voted for another party in 2019 (mainly the ANC), or from people who had not voted in 2019.

Thus, while most parties receive their support from people who voted for them in the previous election, the fact that voters are not consistently party-loyal is epitomised by the flux within the EFF’s support base. This churn also confirms the observation of the EFF presenting a fairly stable percentage of votes, despite not retaining the same voters, from one election to the next, as identified by Paret and Runciman (2023).

Thirdly, the above claims around fluidity do not invalidate notions of party loyalty in South African politics (that is, that voters tend to identify consistently with party). Instead, different parties retain their votes to significantly varying degrees. For instance, only 4% of ANC ‘youth’ voters (people younger than 35 at the time) in 2021 cast their ballot for another party in 2016 (Bekker, Runciman and Roberts 2022). However, the EFF does seem to be a special case, since 35% of its 2021 voters had supported another party in 2016 (based on the Elections Dataset).

Finally, there may be some measure of ideological flow at play. For instance, while there is some movement from the ANC to the EFF (from 2016 to 2019, and from 2019 to 2021), the reverse is not true; based on the present data, former EFF voters tend to vote either for alternative options (‘Other’) or not at all. Of course, the apparently poor voter retention (by the EFF, but also by all parties) may be related to people voting differently in LGEs than in national elections. This implies, all told, that the EFF appears to be a kind of ‘gateway party’ out of the ANC, where voters disillusioned with the ANC (possibly out of desperation, given the country’s levels of services, unemployment and hunger) switch to the EFF, only to subsequently move to smaller parties (which in 2021 included the newly formed, right-leaning ActionSA).

Responses to the open-ended questions in the survey (regarding why a respondent voted for a particular party) further buttress the idea of EFF as a gateway party. For instance, among respondents who voted for the EFF for the first time, responses such as ‘Because [EFF leader, Julius] Malema promise me a lot a things and I want to give him a chance’, ‘I did not see any change on the previous party so I want to give EFF chance as it has promised to better us’ and ‘The EFF has young ideas’ appear instructive.

Discussion

Regardless of context, younger voters are often argued to have a more ‘radical identification’ (i.e. left-leaning values) than their parents (e.g. Maniam and Smith 2017), ostensibly before the ‘traditional effects of ageing’ render them more conservative (Seagull 1971). However, contemporary research suggests that several political attitudes are, in fact, quite stable and change little after the age of 20 (Feitosa and Galais 2020), which appears to appeal to a consistent (as opposed to fluctuating) voter model.

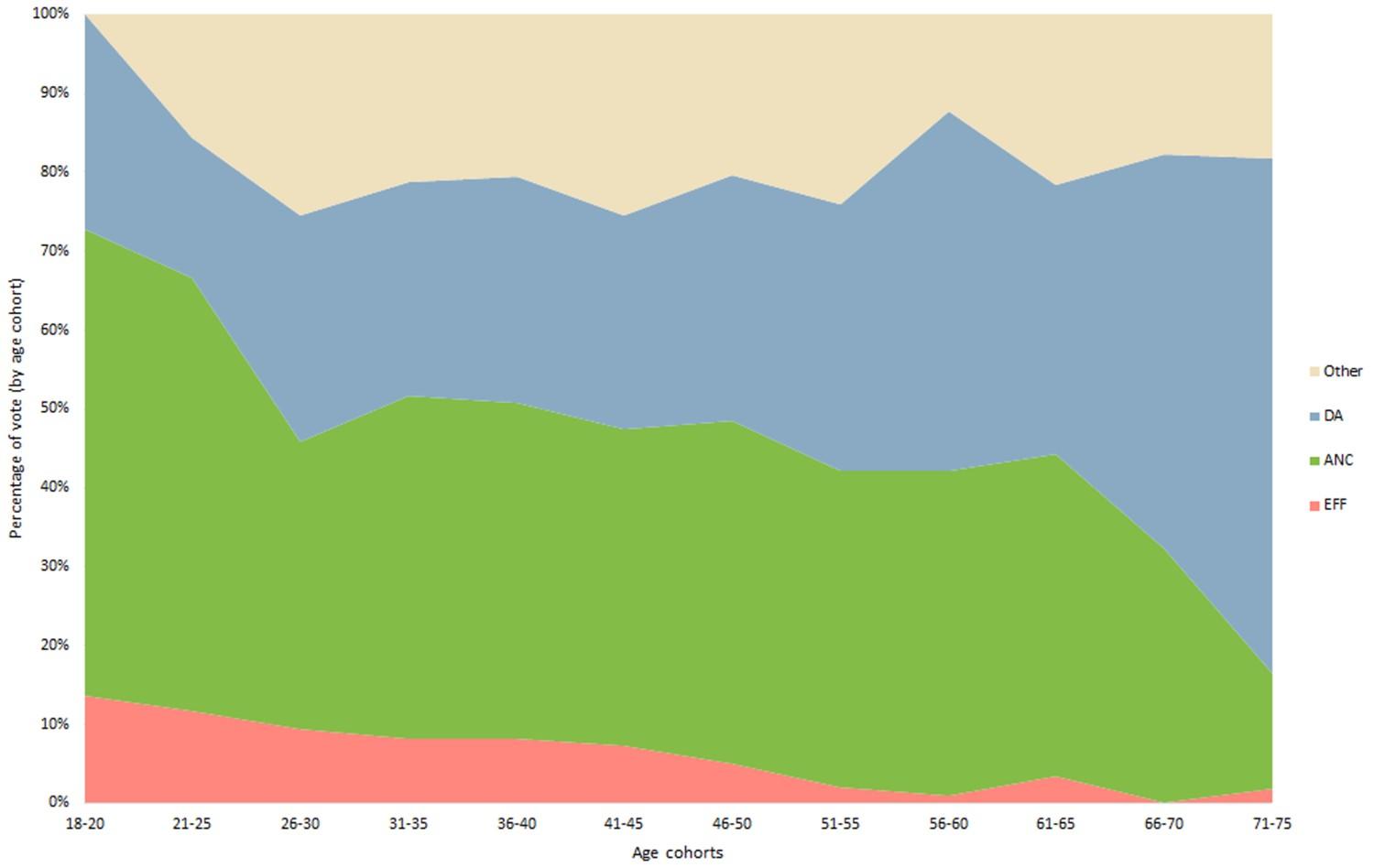

Regarding youth’s supposedly more radical identification, the South African case is instructive. Without a doubt, the EFF remains a party with a youthful support base: 60% of the EFF’s voters were under the age of 37, and no other party at the 2021 LGE presented an equally youth-skewed profile. Figure 2 illustrates how the percentage of votes to the EFF declines as ages increase, a replication of the picture from the 2019 national government election (Runciman, Bekker, and Maggott 2019). Simply put, the older a person is, the less likely they are to identify with the EFF. Potentially offering some insight into that decline, the voter fluidity and ‘gateway party’ arguments appear to suggest it is unlikely that the 12% of young people supporting the party will remain loyal. Rather, barring an exogenous shock, the EFF seems unlikely to grow into a significant contender for dominance in the foreseeable future.

Percentages of cohort vote for the top three parties (omitting ‘refuse to answer’ responses) at the 2021 South African local government election, based on the 2021 University of Johannesburg Elections Dataset.

Questions around the EFF’s leftist positioning (and perhaps credentials) will persist, as will doubts about the party’s project, given the tensions between its rhetoric and practice. The EFF is no longer, as it was in 2014, South Africa’s newest political movement; however, it remains the largest socialist-identifying party. Contemplating the years at the time of the EFF’s formation – including the aftermath of the Marikana massacre, the five-month platinum miners’ strike in 2014, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa removing its support from the ANC, and the ‘Rebellion of the Poor’ (Alexander 2010) – it was a time that saw the weakening of the ANC’s power (under Jacob Zuma) and the reconfiguration of leftist groupings:

a period – a turning point – marked by political fluidity and contradictions, pregnant with possibilities of new political trajectories and futures. In this light, the EFF can be seen as constituting a set of paradoxes, reflecting the fragmented and fluid character of contentious politics, especially among young black South Africans. (Nieftagodien 2015, 448)

Conclusion

The central characteristics of the EFF – what defines it as a party – remain in flux, just as its voter base appears to be fluid. Claiming to be the true inheritor of the ANC’s revolutionary and socialist mandate (Mukhudwana 2021), the EFF represents a radical alternative to the ANC, but one that is plagued by contradictions and inconsistencies, the nature of which have attracted interest from scholars of South African politics and emancipatory movements alike.

Previous studies have intimated that the party is focused on a particularly destitute demograpic, while others have claimed an apparently loyal support base. However, the 2021 UJ Elections Dataset establishes the EFF’s support profile as better than average in terms of both education and wealth. The data not only confirm the support profile as youthful but also show how support tends to wane among older cohorts. In addition, some voters appear to abandon the party after supporting it once or twice, indicating a picture of fluidity, or disloyal support. The fact that the party associated with a pro-poor image might be contrasted with a relatively better-off and well-educated subsection of the youth is to be seen not as ironic, but ostensibly as a consequence of powerful university-based political discourse, while also evoking important questions about the future of leftist consolidation (or disintegration) in the South African party-political sphere.