Introduction

Between 2013 and 2017, there was a series of violent protests and clashes at Adina and adjoining communities at the eastern banks of Keta lagoon1 located on the eastern coast of Ghana. The protests were against the operations of Kensington Salt Industries Ltd.2 Clashes led to deaths and to destruction of property that belonged to the company, including heavy-duty equipment. This was unprecedented in the history of Ghana’s relatively quiet salt sector (except for the protracted conflict at the Songor lagoon area3). The site of these protests and clashes has been the shallower eastern segment of the Keta lagoon which has historically been used for salt production activities by indigenes during the dry season. The indigenes have been producing salt from this area of the lagoon since 1702 when they discovered the technology for so doing (Greene 1988). The technology involves the construction of enclosures or dykes to collect salty water and simultaneously prevent fresh (less salty) water from diluting the salty water in the enclosures, and allowing salt crystals to form through evaporation.

The enduring conflict between the mining-affected communities and Kensington has followed Kensington’s procurement of a mining lease covering a total of about 7300 acres of lagoon surface and adjoining land mass where indigenes in the affected communities previously undertook their salt production activities. According to the Minerals Commission, the government of Ghana has since 2010 granted salt mining leases to three large-scale salt production companies covering a total area of over 20,000 acres in and around the Keta lagoon enclave alone. These have displaced indigenous small-scale producers who have been producing salt on an informal basis for centuries (TWN-Africa 2017). This has raised the spectre of broader conflict between affected communities and large-scale companies. The granting of these leases reflects growing state preference for large-scale mining projects that has moved beyond the traditional minerals (gold, bauxite, manganese and diamond) where large-scale companies dominate, to non-traditional minerals that have historically been dominated by artisanal and small-scale producers.

Dispossession of communities and disruption of livelihoods are not new in the extractives sector. Accumulation by dispossession that includes large-scale ‘grabbing’ of land and natural resources by private capital has been demonstrated to be characteristic of the dynamics of contemporary capitalist expansion (Harvey 2014) and has been analysed through the concept of the neoliberal enclave (Ferguson and Gupta 2002; Lesutis 2019). There is a large body of literature that documents dispossession and displacement of communities associated with exploitation of natural resources by large-scale firms (Bebbington 2012; Kirsch 2014; Hilson 2014). In relation to the dispossession and displacement of communities, large-scale resource exploitation has been associated with loss of livelihoods, environmental degradation, social vices and increased poverty in affected communities (Cernea 1997; De Wet 2006; Adam, Owen and Kemp 2015). In Ghana and elsewhere in much of Africa, community dispossession and associated negative consequences have historically taken place in the so-called traditional minerals sector. This has been largely dominated by foreign capital. Developments in Ghana’s salt sector over the past two decades, however, reflect growing state preference for large-scale projects. While a rich body of literature exists on these issues in relation to gold in particular, there is much less said about non-traditional minerals like salt, which has historically been produced mainly by indigenous artisanal producers.

This article contributes to the nascent literature on how the dispossession of communities and disruption of their livelihoods by growing state preference for large-scale mining projects in the salt sector generate conflict. This is important for a number of reasons that are associated with the differences that exist between traditional minerals (particularly gold) and non-traditional (such as salt). First, a vast body of literature already exists on how dispossession of communities and disruption of their livelihoods by large-scale projects in the traditional minerals sector generate conflict (Akabzaa 2000; Akabzaa and Darimani 2001; Hilson 2002; Aryeetey, Osei and Twerefou 2004). This follows the relatively longer history of large-scale gold mining in Ghana, spanning several centuries, and its dominance in the gold sector since its formal establishment by the colonial government (Tsikata 1997).

Second, while in the case of traditional minerals (particularly gold) the state’s ownership is widely recognised and therefore not in dispute, the same cannot be said about non-traditional minerals (such as salt). Communities in gold-bearing areas have effectively been dispossessed of gold and state ownership, and control established by the state continues to be enforced. Communities in areas where salt production takes place, however, have not yet been dispossessed of the commodity, even though the law says that all minerals (including salt) are nationalised and therefore belong to the state. In practice, therefore, coastal communities have continued to produce salt for subsistence and exchange, but this is now being challenged by the presence of large-scale corporations. Finally, while traditional minerals are exhaustible, salt is less so as its production is based on ocean and climatic conditions. We argue therefore that salt production is much more central to community livelihoods which are being impacted by Kensington than gold production might be in Ghana’s gold-producing areas.

It is against this background that this article contributes to the literature on dispossession of communities and disruption of livelihoods resulting from large-scale projects in the salt sector. Specifically, the study investigates factors that have driven and sustained violent resistance to Kensington’s large-scale salt production activities. The next section presents a background of the salt sector in Ghana followed by an introduction to the methods we used to collect data. We then present an overview of the literature on community violence, and resistance to extractive industry projects, before looking at the key incidents of violent resistance on the eastern banks of Keta lagoon in the recent past. We identify and discuss the factors that have triggered mining-induced violent resistance at Keta lagoon.

Ghana’s mineral economy

Formerly known as the Gold Coast, Ghana is endowed with a wide range of minerals usually categorised into traditional (gold, bauxite, manganese and diamond) and non-traditional (such as salt, clay, limestone and kaolin) (Government of Ghana 2014). In 2007, the country discovered oil and gas resources in commercial quantities, started commercial production in 2010, and has since 2017 been a net exporter of petroleum products. The economy of Ghana has for over a century relied significantly on the mining sector (solid minerals, until recent commercial production of oil and gas) in terms of foreign exchange earnings and government revenue. In 2017 the proceeds from export of solid minerals (mainly gold) exceeded US$6 billion, accounting for 43% of total merchandise exports (Bank of Ghana 2018). There are, however, concerns about the actual export proceeds from the sector that are returned to the country and made available to other sectors. This follows from the dominance of the sector by foreign multinationals with various agreements that allow them to retain a substantial part of their export proceeds for purposes such as paying dividends and servicing loans. In 2013 some members of the Ghanaian Parliament expressed shock that foreign mining companies retained an average of 80% of their annual earnings (Arku 2013).

The contribution of the mining and quarrying sector to domestic tax revenues exceeded 2 billion Ghanaian cedi (GHC), accounting for 16.3% in 2017 (Ghana Revenue Authority 2018). This contribution included workers’ income taxes and pension. Although the sector’s contribution to domestic tax revenues seems appreciable when compared to total domestic revenues collected, it constitutes a smaller proportion of about 7% when compared with the total realised mineral revenue. According to the Ghana Chamber of Mines, the sector directly employed 10,507 in 2017 (Ghana Chamber of Mines 2018). The relatively low number of people directly employed by the sector is a result of widespread capital-intensive surface mining engaged in by virtually all the large-scale mining companies, as opposed to labour-intensive underground mining. Another concern regarding employment is the increasing casualisation of labour and growing income inequality between locals and expatriates (Dadzie 2019; Ankrah et al. 2017). At a broader level, there is widespread questioning and disquiet among citizenry and social groups attributed to poor developmental contributions from the sector (Atta-Quayson 2016; Ayee et al. 2011). The country has been identified as one of the mineral-dependent countries that are most at risk or especially vulnerable to the ‘resource curse’ (Haglund 2011). The export of a few primary and largely unprocessed commodities (minerals, oil and cocoa) contributes a lion’s share of total merchandise export proceeds. These three commodities contributed 85% of merchandise export revenues in 2017 (Bank of Ghana 2018).

As part of the Economic Reform Programmes and Structural Adjustment Programmes supported by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, Ghana reformed its mining sector in the mid 1980s, driven by the policy imperative to privatise the sector by selling state equities in mining companies, providing broad fiscal incentives by way of significant reductions in tax rates and fees, and focusing on government revenues rather than other developmental objectives (Tsikata 1997; World Bank 1992). The Minerals Commission was established in September 1986 under the Mineral Commission Law (Law no. 154) as an advisory body to the Ministry of Mines to provide technical support in the design of relevant policies and the granting of licences/permits. It also undertakes promotional and regulatory functions in relation to mining. With the exception of a few industrial minerals such as salt and sand, whose production for subsistence purposes do not require licences and permits, all other mining activities (reconnaissance, prospecting and exploitation) require licences and permits. The process of obtaining licences differs between large-scale and small-scale operations, with the process for small-scale licences described as overly bureaucratic and taking years to complete, instead of the declared three months needed for processing (Crawford and Botchwey 2017; McQuilken and Hilson 2016). Consequently, most small-scale mining operations are not covered by requisite licences and permits, and are effectively illegal operations.

Environmental protection has not received as much attention as efforts to privatise and attract foreign investment. Although a new mining law was passed in 1986, it took eight years before the establishment (in December 1994) of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which enforced the preparation of environmental impact assessments (EIAs), and another five years before the environmental assessment regulations (1999) were passed to address specific issues.4 The regulations require that proponents of mining projects undertake EIAs and provide mitigation plans for managing negative environmental consequences anticipated from proposed mining projects as a prerequisite for obtaining environmental permits. The process also requires that all communities expected to be affected by such projects are duly consulted and an open forum held in those communities in order to ensure that their grievances and concerns are recorded and addressed. These efforts, establishing the EPA and passing the environmental assessment regulations, followed the largely ineffective operations of the then Environmental Protection Council to protect the environment from the negative effects of various development projects, including mining.

Despite the establishment of an environmental protection regime, the mining industry has continued to contribute to pervasive degradation of the environment (Ayee et al. 2011). Hilson explains that the EPA ‘has been unable to wield its regulatory power to ensure the safe protection of rivers, ecology, and communities from resident mining activities’ (Hilson 2004, 70). These have not been effectively done for a number reasons including weak capacity of the EPA and weaknesses in the regime itself (Akabzaa and Darimani 2001). Akabzaa and Darimani further argue that the ‘national environmental policies have not been able to adequately guard and protect local communities from the adverse impact of mining operations’ (Ibid., 34). The EIA regime, therefore, fails to provide effective protection for communities and the environment.

It took Ghana nearly three decades for a mining policy framework to be published in 2014 following the adoption of the 1986 law signalling the reforms. Although the new policy promises to break away from the largely colonial mining regime that prevails, not much has been done in this direction. The minerals and mining policy framework seeks, among other things, to diversify the country’s mineral production base, promote linkages (backwards, forwards and side-stream), provide opportunities for artisanal and small-scale miners to upscale their activities, ensure a high level of environmental stewardship, and promote social harmony between the mines and adjoining communities (Government of Ghana 2014). Salt features prominently in the framework as far as diversification of the mineral base is concerned. It is envisaged that the salt sector ‘will facilitate and accelerate the development of our oil fields as well as downstream local petro-chemical industry’ and ‘support the proposed integrated bauxite-alumina industry, and the agriculture, food and beverage, water and textiles sub-sectors’ (Government of Ghana 2014, 45). Further to the policy, the sector ministry has been developing fiscal incentives to attract investment into the salt industry (Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources 2015). All these changes have profound implications for artisanal and small-scale salt producers who dominate the sector.

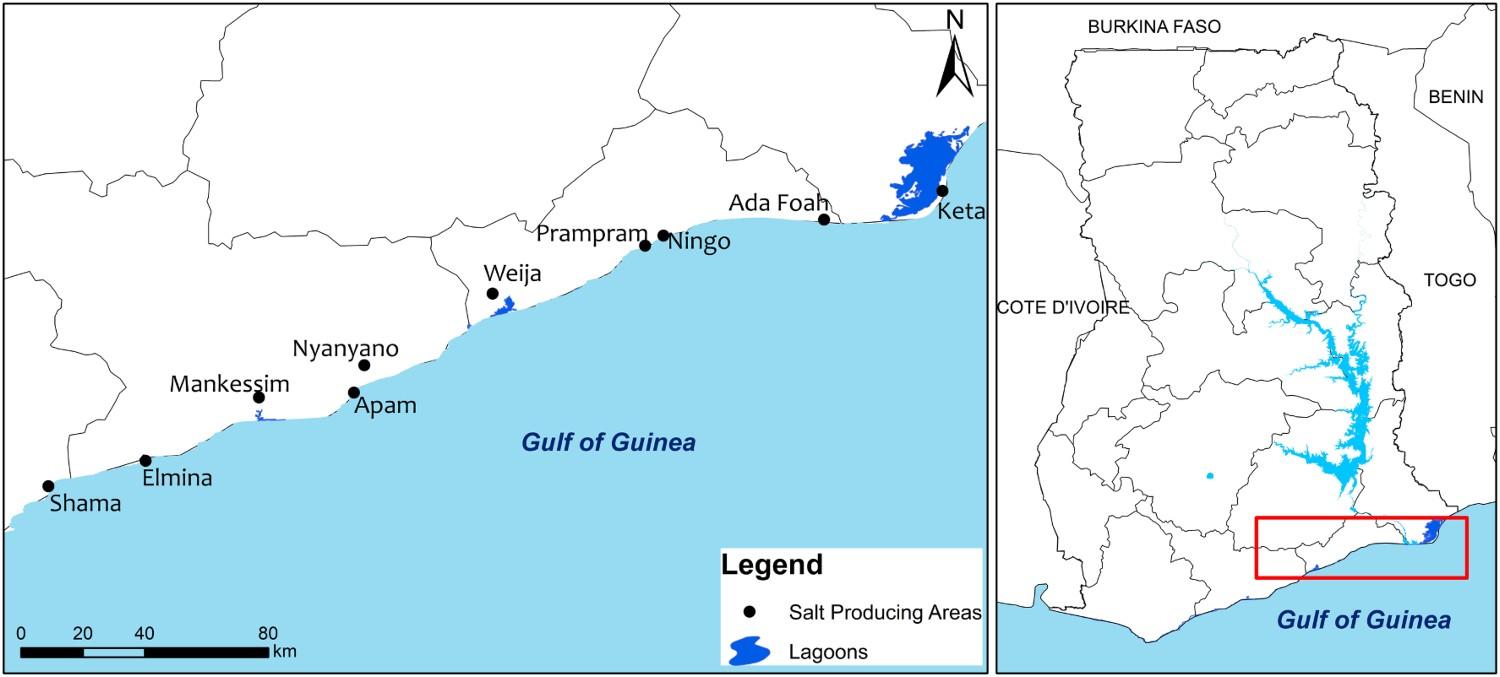

The mining sector in Ghana is dominated by large-scale companies who produce traditional minerals (gold, bauxite, manganese and diamond) for export without much beneficiation and value-added being retained in Ghana. There has been little change in this since the Organization of African Unity’s (OAU’s) Lagos plan of action identified that ‘a considerable dependence on foreign transnational corporations for the development of a narrow range of African natural resources selected by these corporations to supply new material needs of the developed countries’ was a major problem confronting the continent (OAU 1979, 23). The large-scale sector has historically received relatively greater policy attention and support. It is against this background that the salt sector has thrived. Current production (dominated by artisanal and small-scale producers) is estimated to be 400,000 metric tonnes per year despite existing potentials to raise that by more than six times. Figure 1 shows major areas of salt production in the country. There are currently about 10 active large-scale salt producing companies in the sector. With the exception of Ada Songor enclave, where there has been protracted conflict over land tenure and access to the lagoon among key stakeholders (the government, traditional authorities, indigenous producers and some large-scale firms), there has been relative quiet in the entire salt sector.

Map of Ghana showing major areas of salt production. Source: Mohammed Sanda, 2020, University of Education, Winneba.

Indigenous communities in Keta have been undertaking salt mining activities at the eastern bank of the lagoon since 1702 (Greene 1988). The history of how salt production started has important implications for the political economy in which salt production activities take place. According to oral tradition, salt production technologies were introduced in the communities adjacent to the Keta lagoon during the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century with the arrival of Aduadui, founder of the Dzevi clan, and the flooding of refugees to the Anlo area in 1679 (Ibid.). In this way, individuals with the know-how controlled their production activities just as they did as regards fishing and farming. Overtime, salt production evolved into communal artisanal activities dominated by women, in which traditional authorities had relatively less control and influence. Different clans and families lay claim to segments of the lagoon and its banks where salt production activities took place. This is in spite of statutory provisions that mineral resources in their raw state and major water bodies (including the ocean and Keta lagoon) are the property of the state. Prior to Kensington obtaining its mining lease and subsequent production activities, there were vibrant artisanal and small-scale salt production activities. This is in contrast to the case at Ada Songor where from the early days of salt production traditional authorities had greater influence and control of the sector (Langdon and Larweh 2017).

Kensington Salt Industries

Kensington Salt Industries Ltd (now Seven Seas Salt Ltd), was incorporated in Ghana in March 2009 and identifies as a British conglomerate that deals in salt and salt-related activities. It is related to a large Nigeria-based company, M/S Royal Ltd (also known as Royal Salt Ltd) which imports salt from Namibia, Australia and Brazil for further processing and sale in West Africa. The company acquired part of its current concession from West African Goldfields Ltd (WAGL) and obtained approvals from the Minerals Commission and the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources for its acquisition of WAGL’s concession. Its new lease granted by the Ministry took effect from 29 December 2011 and lasts till 28 December 2026. The company currently holds 7299.41 acres of land in its concession, comprising 2410.56 acres (Adina concession); 3593.92 acres (Agavedzi and Blekusu concession); and 1294.93 acres (additional Adina concession for salt field expansion).

According to an interview with a former small-scale salt producer at Adina, prior to Kensington taking over WAGL’s concession, about 50 small-scale salt producers organised themselves into an association and obtained part of WAGL’s concession for their operations. The Minerals Commission was a witness to the agreement signed between WAGL and the association of small-scale producers which paved the way for the construction of various ponds by the members of the association and other related investment for their salt production activities. With the arrival of Kensington, the agreement was immediately annulled, leading to members of the association losing their investments. Efforts to get the Minerals Commission to intervene on their behalf proved futile, as the Commission favoured large-scale operations. This has been at the heart of the violent resistance against Kensington’s operations. Most artisanal producers, the majority of them women, had their livelihoods threatened and received no compensation.

Kensington has held various meetings with a range of stakeholders, particularly chiefs and opinion leaders of communities affected by its operations, in an attempt to find a way to manage the growing discontent among the catchment communities of its operations. There has been no such meeting with the small-scale producers who were organised and operated on what became Kensington’s concession. An agreement reached with chiefs to develop part of the concession for catchment communities for salt production activities has not been fulfilled. The company cites disagreement among chiefs and opinion leaders as the main impediment to fulfilling that part of the agreement. With the people most affected by the company’s operations (especially local producers) excluded from such meetings, the success of this approach has been very limited, as agitations, demonstrations and violent resistance against its operations have grown. Company operations were suspended in June 2017 for a couple of months following a demonstration in which the underground water-pumping infrastructure was deliberately destroyed.

Community dispossession, disruption of livelihoods and conflicts

The process by which protest, resistance and conflicts (violent or otherwise) arise and evolve in relation to natural resource exploitation is complex. While the resistance and ensuing conflicts are usually initiated by affected communities to register their opposition to extractive industry activities (especially in Latin America), it has also been noted that some conflicts (especially in Africa) are actually perpetrated by extractive sector companies with the support of state security apparatus such as the military and police. The latter phenomenon has been described as ‘privatization of the means of coercion’ (Mbembe 2001, 79) and involves the use of state security services to suppress local resistance to accumulation by dispossession.

There is a long history of resistance and conflicts associated with natural resources. Academic interest has been active in the last 40 years. Le Billon (2005) reveals that since the 1980s, about a third of civil wars and armed conflicts around the world have been financed by revenues from natural resources (such as timber, diamonds and narcotics), suggesting that exploitation of the resources go hand in hand with armed conflicts. This suggests that current resource-induced resistance at Keta has the potential to be prolonged and to evolve into much bigger conflict. Silberfein and Conteh (2006) demonstrate how porosity and contestability of boundaries feed protracted conflicts. Using the Manor River region (made up of Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia and Cote d’Ivoire) as a case study, the authors show how conflict starts from one country and spreads through others within the region facilitated by easy flow of weapons, movement of former combatants and transnational exploitation of resources. Silberfein and Conteh identified exploitation of resources such as diamond, gold, timber and rubber (especially by rebels) as a major contributory factor that fuels and deepens the conflicts. Another important determinant of resource conflict is resource prices and therefore demand patterns for the resources in question. McNeish (2018) notes a rise in resource conflicts as a result of the expanding frontier of extraction following increased demand and prices for resources.

Obi (2010) discusses transformation in resistance from non-violent to violent approaches, involving attacks by militias against oil companies, which have characterised oil extraction in Nigeria. Like the situation at Keta, the Niger Delta resistance was noted to have been fuelled by the dispossession of local people and the feeling of anger among them resulting from inequitable distribution of oil wealth among a range of stakeholders.

Downey, Bonds and Clark (2010) have argued that the use or threatened use of violence is a part of the mechanisms used by wealthy nations and corporations to either gain or maintain access to natural resources. They argue that apart from violence, wealthy and powerful nations and corporations ‘have created overlapping institutional, organisational, ideological, legal, and technological mechanisms that provide them with the means to prevail over others in conflicts over natural resource use, extraction and transport’ (Ibid. 2010, 421). The situation at Keta lends some credence to this observation, given the deployment of the Police Service to defend the company and in some cases behave violently to local residents. Downey et al. (Ibid.) theorise that continuous natural resource exploitation is enabled by the use and threatened use of armed violence.

Literature on how community dispossession and disruption of livelihoods related to natural resource exploitation activities in Ghana has been focused largely on the traditional minerals sector. Akabzaa and Darimani (2001), assessing the impact of mining sector investment in Ghana with a focus on the Tarkwa mining region, found that heavy concentration of mining activities (predominantly large-scale projects) generates environmental and social issues such as destruction of sources of livelihoods that invariably induce a spate of resistance and clashes between affected communities and large-scale mining companies. Hilson and Yakovleva (2007) present a case of encroachment by indigenous gold miners for the purposes of mining on the concession of Bogoso Gold Ltd, a foreign-controlled large-scale gold mining company. The study showed how indigenous miners ignored directives of the company to stay away from its concession, citing the company’s little interest in those areas where the miners were encroaching and lack of jobs in the catchment communities.5 Langdon and Larweh (2017) focusing on the salt sector describe how social movement mobilisation at the Songor enclave has has prevented corporate accumulation at the cost of community dispossession, despite the complicity or lack of action of the leadership in the area.

In the light of the above, our study was influenced by the ‘critical incident technique’ and ‘involves asking a number of respondents to identify events or experiences that were “critical” for some purposes’ (Kain 2004, 71). We asked how resistance against resource extraction activity had turned violent. The research design was an exploratory, descriptive and interpretative case study which employed qualitative data collection methods. The case under study, and the unit of analysis, were constituted by the operations of Kensington and all nearby communities affected by those operations. The choice of Kensington’s project was purposive and followed news in the media about growing violent resistance against its operations.

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews of representatives of state agencies and the company, as well as of other key informants who live in the catchment communities of Kensington’s salt operations, were conducted in 2016. We used purposive and snowball sampling techniques interviewing 19 people in the communities, including a couple of chiefs, opinion leaders, salt miners and ordinary residents at Keta and other adjoining communities. Two officials of the company, three government officials (from the Municipal Assembly, Minerals Commission and EPA), two officials of extractive-focused non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (African Challenge and Ketu-Keta Salt Winners Association), and three journalists who have covered and reported on the incidents were also interviewed. Primary data were supplemented by secondary sources by reviewing major Ghanaian newspapers (print), online news portals and other related literature. The resistance and conflicts surrounding Kensington’s operations were widely covered in major newspapers and online portals. In terms of analysis, the case study adopted what may be referred to as ‘incidence analysis’ as opposed to thematic analysis, within a grounded theory analytical framework. This analytical approach in grounded theory is an iterative process where data collection and analysis take place concurrently: insights from initial incidents influence further data collection, which improves understanding of a particular phenomenon (Chapman, Hadfield and Chapman 2015).

Key incidents of violent resistance and clashes against Kensington at Keta

2 . December 2015

A group of local salt miners from Adina and other neighbouring communities protested against the operations of Kensington Salt Industries Ltd, accusing the company of taking their livelihoods from them. The local salt producers complained that a road being constructed by the company passes through their salt ponds, destroying the ponds and all efforts put into them. In the demonstration, the salt miners and residents who protested were reported to have attacked some workers and burnt a tipper truck and excavator belonging to the company. In the process, the Keta police commander was hit on the head with an object by one of the demonstrators, while another took the commander’s duty pistol and tried to shoot him at close range, but failed as the gun was locked. Five local salt miners and three policemen sustained various degrees of injuries as the demonstrations turned violent. The police confirmed the arrest of 16 people in connection with the demonstration (Ghana News Agency 2015).

17 . March 2017

The youth of Adina went on a demonstration at Kensington’s premises to protest the arrest by the police of four women accused of collecting salt from the Kensington concession. The demonstration turned violent when the youth clashed with Kensington workers. The youth were reported to have assaulted the workers on site, vandalised the company’s property and pilfered valuables, including computers and motorbikes. The police intervened in the situation to try to calm it down, but unfortunately the situation rather escalated as one of the youth – Atsu Nkegbe – died from gunshots (described by the police as ‘stray bullets’). Two other people who were hit by these ‘stray bullets’ were severely injured and had to be sent to the Korle Bu teaching hospital in Accra (Duodu and Razak 2017; Akpablie 2017a; author interview with a resident).

29 . March 2017

Hundreds of residents of Agbozume and Klikor in the Ketu South municipality went on demonstration on Wednesday 29 March 2017 to protest against what they described as adverse effects of Kensington Salt Industries Ltd on their livelihoods. Clad in red attire, the aggrieved residents marched several kilometres from Agbozume to Denu-Tokor, where the Municipal Assembly is located. They presented their petition through the Municipal Assembly to the government of Ghana. They complained that the company had failed to comply with the agreed terms of engagement and has rather brought hardship to the people affected by their operations. As we noted earlier, they accused the company of causing the lagoon to dry up, thus undermining fishing communities at Agbozume, Klikor and Adina (Starfmonline.com 2017; Akpablie 2017b).

Triggers of mining-induced violent resistance and clashes at Keta

Having identified three major incidents of violent resistance and conflict characterising operations of Kensington, the authors then interviewed key stakeholders about the dynamics and factors leading to these incidents. The literature identifies destruction of livelihoods and negative effects on the environment as the main reasons for violent resistance and conflicts associated with natural resources exploitation (see for example Obi 2010; Hilson and Yakovleva, 2007; Akabzaa and Darimani 2001). However, the nuances of these factors observed and for example the issue of flawed EIA processes improve our understanding of these incidents and how better to handle them. Four major factors that were identified are presented and discussed below.

Non-payment of compensation

Among the 19 people interviewed, the issue of non-payment of compensation by Kensington was identified as the major rallying point that triggers violent demonstration and confrontation with the company. One small-scale miner pointed out that ‘unless and until the company fully compensates people who have lost their “spaces”, there will always be troubles.’ The issue of non-payment of compensation implicates the land tenure system that applies in the area and the fact that water bodies (including the Keta lagoon) are nationalised. During an interview with some management members of Kensington, the company admitted that it has not paid compensation to anybody and argued that it was not liable to pay compensation because the area was not under mining at the time it took over. Throughout the country, most artisanal and small-scale miners do not have the requisite licences covering their operations, and state agencies do not officially recognise them.

Kensington’s argument went beyond this and claimed that a road constructed in the 1990s prevented the flow of seawater into the lagoon, leading to the part of lagoon where its concession is located drying up. Thus, the site could no longer support fishing and salt mining activities as claimed by the indigenes. Artisanal and small-scale salt miners, other residents of affected communities and officials of the Municipal Assembly interviewed denied this assertion and indicated that the lagoon obtained sufficient fresh water after every rainy season and supported both fishing and salt mining activities for the rest of the year. According to the planning officer, for example, there are tens of small-scale salt miners and hundreds of artisanal miners who are periodically educated on the need to iodise salt produced in the area through a project supported by development partners such as the World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund.

The non-payment of compensation by Kensington is a rudimentary form of accumulation by dispossession characterising contemporary capitalist expansion (Bebbington 2012; Harvey 2014). It is contrary to provisions in the Constitution and mining law, thereby raising questions about how the firm obtained the green light from key state agencies such as the Minerals Commission and the Ketu South Municipal Assembly. The feeling of strong disappointment among people due to the non-payment of compensation mirrors similar developments at Niger Delta which influenced and shaped the emergence of MEND, the Movement for Emancipation of Niger Delta (Obi 2010).

Ineffective EIA processes

In December 2015, the Municipal Chief Executive (MCE) of Ketu South (where Kensington’s salt mining project is largely located) was reported to have admitted that ‘the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) failed to undertake proper environmental impact assessment before the license was granted to the company’ (Emmanuel 2015, added emphasis). This sentiment was confirmed by officials of the Ketu South Municipal Assembly that were interviewed, as well as representatives of communities affected by Kensington’s operations. Although the EPA does not ‘undertake environmental impact assessment’, it facilitates a range of activities that lead to the awarding of an environmental permit. The remarks of the MCE can be viewed as implicating the credibility of the EIA procedures, as earlier observed by Akabzaa and Darimani (2001) and Hilson (2004). Further, the demonstrations that have taken place regarding Kensington’s operations and the decision by the firm to cede and develop about 30% of its concession to affected communities clearly show that there is something wrong with how these procedures are undertaken.6

All efforts by the authors to obtain a copy of the environmental impact statement which provides information on what EIA procedures were undertaken by the company failed. These efforts included a search at the EPA library in Accra by the librarian, and requests for a copy of the document made to the Ketu South Municipal Assembly and Kensington Salt Industries Ltd. The company insisted that the document is a ‘work in progress’ so it would not share a copy with the authors, and neither would it share a copy with any member of the affected communities who put in a similar request. At the Assembly, all the principal officers interviewed indicated that they themselves have not seen a copy of Kensington’s environmental impact statement and wondered if the Assembly actually had a copy of the statement, even though they admitted that the Assembly ought to have a copy of the document. The likelihood of conflict being particularly high when environmental assessment practices are weak has been observed in the literature (Li 2008).

Impacts on jobs, livelihoods, women and children

One of the main arguments in support of large-scale operations in the mining sector has been the ability of companies to create ‘decent jobs’ in ‘large quantities’, especially for people in their catchment communities. Yet evidence on the ground shows that while they are capable of creating some decent jobs, the numbers are not encouraging. This is particularly so when ‘decent jobs’ created by large-scale operations are compared with jobs that were shed to pave way for their operations. The posturing of the state and its determination to woo investors into the sector with various incentives (especially fiscal) rather than supporting local artisanal and small-scale producers is therefore risky. Actual figures of jobs that have been destroyed in connection with Kensington’s operations are difficult to ascertain. Nonetheless, an official from African Challenge (a local NGO in the salt sector) estimates that more than 60,000 people have been displaced and several thousands of jobs have been directly affected or destroyed by Kensington’s operations (Asare 2019). This figure easily dwarfs the number of jobs that have been created by the company. In an interview, the general manager of the company indicated that it has created jobs for about 600 people and is still hiring.

Some workers interviewed on the ‘decency’ of their employment expressed concerns that do not support the view that jobs created by the company are indeed in that category. One of the workers interviewed said that ‘while head porters earn GHC10 a day, other workers (such as those who operate equipment) earn GHC15 a day.’7 Although not enthused about the work they do and the remuneration, they felt compelled to pick up those jobs given the circumstances they found themselves in (mainly lack of jobs in the communities). They also expressed concern about the health and safety conditions of their work. Many workers do not have personal protective equipment and clothing such as gloves and wellington boots, according to some of the workers interviewed. They admitted that many of the workers without safety equipment would not agree (as once suggested by officials of the company) to stay home for a while until the company acquired additional safety equipment. This is largely a result of the harsh joblessness conditions that local workers live in.

The significant role played by women in salt mining in Ghana means that the resettlements that follow a takeover of mining areas by large-scale operators have a disproportionately greater impact on women (and therefore children). With approximately two-thirds of artisanal and small-scale salt producers being women, and more than three-quarters of the labour force in the salt sector being women, they tend to bear the greater burden of the fallout of jobs and livelihoods destroyed in the wake of large-scale operations in the salt sector. Further, unemployment in general affects women and children more as they dominate the segment of population that is dependent. In an interview, a female representative of an artisanal salt miners' association at Adina with four children lamented that ‘we struggle to feed our families following the takeover of the salt producing area by Kensington.’ No one from her household has been recruited to work by the company. Meanwhile in the past, they could mine salt and sell it to support their household expenditures.

Increased salinity and drying up of hand-dug wells

The manner in which Kensington operates its salt mining is cited as being responsible for some environmental threats that affected local communities. Some of these relate to water shortages, as hand-dug wells have dried up. This development is believed by some residents to have been caused by Kensington drawing underground water for its production of salt rather than using brine/seawater. In other communities, there have been reports that the taste of coconut in the areas had changed and become saltier. Again this was attributed to the use of underground water by the company for its production. Emmanuel (2015) reports that one of the salt miners expressed the worry that

the fresh water, that used to flow from Togo into the lagoon, bringing in fish in the rainy season has been blocked by roads and dams constructed by the company. As a result the annual fishing and salt winning seasons that used to bring relief to the people have become a thing of the past since the lagoon dries up prematurely. (Emmanuel 2015)

Conclusions

We have begun to trace violent resistance and conflict that followed community dispossession and disruption in livelihoods resulting from a large-scale salt mining project on the eastern banks of the Keta lagoon. We have contributed to the literature on accumulation by dispossession and the neoliberal enclave. Our study demonstrates the evolving preference of the Ghanaian state for large-scale mining projects that extends to non-traditional minerals like salt. Moreover, the differences that exist between traditional and non-traditional minerals mean that the Keta lagoon community has been impacted significantly by Kensington’s mining operation which has led to sustained and violent resistance. Acts of resistance and conflicts generated by large-scale projects are fluid, with each case offering nuances that can improve our understanding of resistance and may help identify the triggers that generate conflict.

The triggers for conflict at Keta were familiar in the debate about communities impacted by mining. They included non-payment of compensation, ineffective EIA processes, and destruction of livelihoods. We have argued in addition that because salt production was such a significant part of local livelihoods, the level of resistance and ensuing conflict have been more protracted than perhaps in other areas of Ghana’s extractives sector. A possible resolution of conflict may revolve around the state moving away from its preference for large-scale projects and focusing rather on scaling up activities of dominant artisanal and small-scale producers, as provided for in the minerals and mining policy framework. The resistance and conflict at Keta also reflect other structural concerns such as weak political representation and inadequate avenues for addressing local dissent.