Introduction

The cultivation and harvesting of agricultural commodities in Africa supplies consumer markets in Europe with an impressive variety of food and beverage products, yet widespread human suffering persists among those who perform such essential production activities. Many cocoa farmers in the Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, where 60% of global cocoa is produced, reportedly live on less than $1.50 a day (True Price 2017). Numerous media investigations and documentaries over the last decade, such as ‘The dark side of chocolate’ (Mistrati 2010), ‘The children working the tobacco fields’ (Boseley 2018), ‘Black gold’ (Francis and Francis 2006) and ‘Starbucks and Nespresso: the truth about your coffee’ (Barnett, Mistrati and Burge 2020), have exposed how producers earn poverty wages and are denied their rights to decent working and living conditions.

Academic and civil society research into global value chains (GVCs) shows that producers commonly earn less than 10%, and in many cases less than 5%, of the final sale prices of the food and beverage products they help to produce (Fitter and Kaplinksy 2001; Daviron and Ponte 2005; Agrifood Atlas 2017; IPES-Food 2017; True Price 2017; Morales-de la Cruz 2019). Their share of value has fallen dramatically in recent decades, representing an acceleration of a worrying long-term trend of relative producer income decline. In 2018, research commissioned by Oxfam found that the average income share received by producers of 12 different commodity products in 12 different countries in the global South declined by 26% between 1998 and 2015 (Oxfam International 2018).

Conventional explanations largely dispute whether issues of competitiveness or issues of market power better explain why production activities generate less value. On the one hand, the value-added narrative suggests that European firms are more productive than African firms in their respective activities, i.e. that they are capable of adding more value to the final product for the same cost (Porter 1990; Subramanian 2007; World Bank 2017). On the other hand, the body of academic research dedicated to the study of GVCs (value chain analysis) describes how large-scale buyers exercise power advantages over small-scale producers to manipulate prices (Gereffi and Korzeniewicz 1994; Fitter and Kaplinksy 2001; Gereffi et al. 2001; Ponte 2002; Ponte and Gibbon 2005).

Both these explanations focus on the relationships and the nature of the competition between firms as buyers and suppliers along GVCs. This firm-centric approach often leads to the assertion that market forces, such as the importance of brand recognition and marketing strategies, explain why production activities seem to generate less value. However, the determinants of price levels at different stages of the value chain are complex and multi-faceted, and also result from the interplay of non-firm institutions, policies, laws and negotiations (ILO 2017). The imperialist perspective on GVCs provides an explanation that also considers the role of public institutions, suggesting that the facilitation of agribusiness interests through international policy has helped create a system of value capture, in which transnational corporations control production and suppress prices for agricultural commodities (Harvey 2003; Smith 2012, 2016; Amanor 2019; Selwyn 2019; Suwandi 2019).

To explore this further, and to examine the extent to which European public institutions, policies, laws and negotiations contribute to the levels of poverty experienced by Africa’s coffee and cocoa producers, this briefing analyses trading through a whole-markets systems lens. This type of analysis looks beyond interfirm dynamics to identify systemic factors that differentially affect large groups of similar firms (ILO 2017). In addition to widely discussed changes in technology, communications and consumer preferences, the ongoing crisis faced by Africa’s coffee and cocoa producers can be attributed to the suppression of supply management at the international and national levels, and to the indulgence of European agribusiness through favourable domestic competition, corporate tax and regulatory policies. European governments have an imperative to safeguard the availability of cheap and reliable imports of critical agricultural commodities for domestic consumers, and also to support the growth and competitiveness of their domestic agri-food sectors, hence their use of foreign and competition policy tools to suppress the organisation of global production and support the concentration of European manufacturing and retail. The structure of this briefing is as follows: the second section reviews the recent evolution of coffee and cocoa trading outcomes; the third section outlines recent key legal, institutional and regulatory changes; the fourth section considers the role and objectives of European governments; and the fifth section contains conclusions.

Trading outcomes

As two of the most widely studied commodities, numerous sources present data on the relative mark-ups (the percentages by which the prices of products increase before they are sold again) of the primary groups of firms (producers, traders, processors, manufacturers and retailers) operating along the coffee and cocoa value chains. This section analyses a number of these sources to outline how trading outcomes have evolved in recent decades.

Coffee

Within the coffee market system there are individual markets for green coffee, roasted coffee and soluble coffee products, as well as a wide range of more differentiable, consumable coffee products. Most value chain analysis studies calculate the mark-ups at each stage of production using the difference between average buying and selling prices, as a share of the final retail sale price. As a prominent example, Daviron and Ponte (2005) reported that Ugandan coffee producers received 6.6% of the final retail price. This body of research shows consistently that the highest mark-ups are found at the manufacturing and retailing stages of the coffee value chain.

Since studies using this methodology typically present data only for a single year, difficulties arise in examining the evolution of trading outcomes over time. However, re-export data published by the International Coffee Organization (ICO) contains average annual import and export figures broken down into distinct time periods: 1965–1990, and 1990–2010 (ICO 2012). To consider recent trends, figures for 2000–2010 are also provided, but comparable data are not yet available for the years since 2010. Since bulk coffee trading only includes green, roasted and soluble forms of coffee, the final stages of retailing and marketing to the final consumer are neglected in these data.

Table 1 below breaks down the average prices per kilogram of coffee received by each of the four leading African coffee exporters, and the four leading European coffee re-exporters. Only four African countries were included in the study, but since the basis for the inclusion of each exporting country was their individual share in global coffee production (measured using average volume exported over the period), this group is considered to represent Africa’s leading coffee exporters. The four European re-exporters were selected as the countries that re-exported the highest proportion of their coffee imports over the period studied.1 Between 1965 and 1989, the data show that the top African coffee exporters earned, on average, 34% less than the top European re-exporters per kilogram of coffee. Between 1990 and 2010, African exporters earned an average of 66% less, with 2000–2010 data showing the differential was greater (76%) in the years after 2000. This is largely because the mark-ups found at the coffee processing and manufacturing stages have increased dramatically at the expense of producers in recent decades. During the 2000s, a kilogram of African coffee was re-exported from Europe at an average mark-up of $4.11 (over 300%), compared to $1 (52%) during the 1970s and 1980s.

Average annual price received per kilogram of coffee exported, 1965–2010 (in US dollars).

| African exporter | Average annual price received per kg of coffee exported | European re-exporter | Average annual price received per kg of coffee exported | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965–1989 | 1990–2010 | 2000–2010 | 1965–1989 | 1990–2010 | 2000–2010 | ||

| Côte D’Ivoire | 1.96 | 1.29 | 1.12 | Belgium | 3.54 | 3.09 | 3.00 |

| Uganda | 1.60 | 1.98 | 1.18 | Switzerland | 1.85 | 10.31 | 11.67 |

| Ethiopia | 2.27 | 2.45 | 2.3 | Germany | 3.65 | 3.24 | 3.11 |

| Cameroon | 1.87 | 1.21 | 0.74 | Netherlands | 2.66 | 3.89 | 4.03 |

| Exporter average | 1.93 | 1.73 | 1.34 | Re-exporter average | 2.93 | 5.13 | 5.45 |

Source: ICO (2012); author’s own calculations.

As further evidence of trading outcomes becoming more unequal in recent decades, the data show that the selected European countries were able to extract higher mark-ups over the period shown on coffee re-exported in the same form as it was imported. Between 1965 and 1989, re-export prices of green coffee were an average of 16% higher than export prices of green coffee, rising to an average of 29% higher between 1990 and 2010, and 34% higher between 2000 and 2010. Some selection of beans based on their quality often takes place prior to re-export, which may explain part of this differential. Nevertheless, this is indicative of the broader pattern of coffee trading, roasting and manufacturing mark-ups increasing at the expense of production mark-ups. As a result, many coffee farmers are now estimated to be worse off now than they were in the 1970s or 1980s (Morales-de la Cruz 2019).

Cocoa

Within the cocoa market system there are individual markets for raw cocoa beans, semi-processed cocoa products (e.g. cocoa butter, liquor or powder), industrial chocolates and a wide range of differentiable, consumable chocolate products. Table 2 below breaks down the share of the final sale price at each stage of the cocoa value chain, as reported by the 2015 Cocoa Barometer Report (VOICE Network 2015). This shows that, similarly to coffee, the highest mark-ups are found at the manufacturing (35.2%) and retailing (44.2%) stages.

Mark-up per tonne of sold cocoa at each stage of the cocoa value chain, 2015.

| Stage of production | Buys (US$) | Sells (US$) | Mark-up (US$) | Mark-up as share of final sale price (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exporting countries | Farmers’ income | 664 | 1874 | 1210 | 6.6 |

| Inland transport | 1874 | 1971 | 97 | 0.5 | |

| Taxes/marketing board | 1971 | 2745 | 774 | 4.2 | |

| Re-exporting countries | International transport | 2745 | 2793 | 48 | 0.3 |

| Costs at port of arrival | 2793 | 2993 | 201 | 1.1 | |

| International traders | 2993 | 3038 | 45 | 0.2 | |

| Processors and grinders | 3038 | 4434 | 1395 | 7.6 | |

| Manufacturer | 4434 | 10,858 | 6425 | 35.2 | |

| Consuming countries | Retail/taxes | 4434 | 18,917 | 8058 | 44.2 |

Source: VOICE Network (2015).

Again, difficulties arise in using this data to examine how outcomes have evolved over time, but in the absence of annual bulk cocoa export data as consistently available as coffee, one option is to compare the producer share of the final sale price calculated at different points in time. A 2017 report into the overall agri-food industry, the Agrifood Atlas, reported that cocoa farmers in 1980 received a 16% share of the final sale price (Agrifood Atlas 2017). This is considerably higher than the 6.6% calculated for 2015 (VOICE Network 2015) and indicates that, similarly to coffee, mark-ups at the cocoa processing and manufacturing stages have increased dramatically at the expense of cocoa producers. This assessment is further supported by the fact that the average annual price of cocoa beans has declined steeply since the early 1980s, and was lower in 2015 than at any point in the previous 160 years, excluding a handful of years during which major global crises occurred (Ibid.) As a result of these patterns, many African cocoa farmers are also estimated to be poorer now than they were in the 1970s or 1980s (Odijie 2019).

Legal, institutional and regulatory changes

In response to these worrying price trends, value chain analysis studies have recently begun to focus on the underlying determinants of how GVCs are organised and coordinated (Ponte and Sturgeon 2014; Yeung and Coe 2015). A number of studies have attempted to define the ways in which power is exercised in GVCs to protect and appropriate economic rents (Davis, Kaplinsky, and Morris 2018; Dallas, Ponte, and Sturgeon 2019), and this section draws upon the insights of this literature to track and compare the key institutional, legal and regulatory changes that have taken place in the coffee and cocoa sectors, in order to explore the link between these changes and the shifting of mark-ups to the processing and manufacturing levels of the coffee and cocoa value chains.

Coffee

There is broad scholarly agreement that the global coffee market system passed through three distinct institutional phases in the post-World War II period. Grabs and Ponte (2019, 811) define these periods as ‘the “ICA regime” phase (1962–1989); the “liberalisation” phase (1990–2007); and the “diversification and reconsolidation” phase (2008–present)’. These phases align closely with the three data periods used in the ICO’s 2012 ‘Re-exports of coffee’ report (ICO 2012).

During the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) period from 1962 to 1989, there were agreed export quotas and target price zones in place to manage supply and govern trading between most coffee-producing and coffee-consuming countries (Fitter and Kaplinksy 2001; Ponte 2002; Newman 2009; Bargawi and Newman 2017; Behuria 2019; Grabs and Ponte 2019). Prior to the 1990s, African coffee production was also typically organised through national, state-owned marketing boards, which were responsible for buying commodities, setting prices, regulating quality and coordinating sales through auctions (Wanyama, Develtere, and Pollet 2009; Bargawi and Newman 2017; Wedig and Weigratz 2018). These organisations were far from perfect, often inefficiently managed and vulnerable to capture by elites, but they performed a vital intermediary role between often small-scale coffee producers and global traders (Wedig 2019).

The ICA ended in 1989, which ushered in a more liberalised and volatile phase in the absence of agreed export quotas and price zones managing global supply (Fitter and Kaplinksy 2001; Ponte 2002; Daviron and Ponte 2005; Newman 2009; Bargawi and Newman 2017; Vicol et al. 2018; Behuria 2019; Grabs and Ponte 2019). Simultaneously, the process of structural adjustment in producing countries sought to limit state involvement in coffee production, resulting in the widespread dismantling of national coffee marketing boards and producer cooperatives in the 1990s (Wanyama, Develtere, and Pollet 2009; Bargawi and Newman 2017; Wedig and Weigratz 2018; Wedig 2019).

In the years following the 2008 financial crisis, the coffee market system entered a third institutional phase characterised by a wave of consolidation amongst coffee roasters and manufacturers. The harsh economic conditions following the financial crisis forced a number of multinational roasters that ‘previously held great market power’ to seek exit from the market (Grabs and Ponte 2019, 811). Lead firms absorbed many of their closest competitors and, by 2012, the world’s three largest coffee traders (Volcafe, Neumann Kaffee Group and Ecom) handled just under half of the world’s green coffee imports, whilst two roasters (Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts) together controlled over 40% of the global market for roasted coffee (Troster and Staritz 2015). Since over 75% of coffee consumed is purchased in retail stores (Behuria 2019, 358), the 10 supermarkets that account for over half all grocery sales in the European Union also enjoy substantial control over the global coffee market2 (Agrifood Atlas 2017). In other words, a small number of large multinational trading, roasting and retailing firms, mainly located in Europe, have come to buy and sell the majority of the coffee that is produced by an estimated 25 million small-scale farmers around the world.

Cocoa

Cocoa trading was also governed by a system of guaranteed prices and export regulation prior to the 1990s (Kaplinsky 2004; UNCTAD 2004; Ponte and Gibbon 2005; Neilson et al. 2018). Liberalisation of cocoa did take place more gradually, as it was governed by multiple agreements (UNCTAD 2004), but, by 1993, most agreements had been suspended and there were no provisions for previously utilised supply management mechanisms such as buffer stocks and price ranges (Ibid.). Cocoa production was also more organised at a national level prior to the 1990s. Marketing boards in anglophone countries (e.g. Ghana and Nigeria) and centralised funds in francophone countries (e.g. Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon) effectively guaranteed a producer price, but these structures had largely disappeared from African cocoa-producing regions by the end of the 1990s. Multinational traders, many of which are European, now control the cocoa-exporting process in most African countries (Ibid.).

In terms of more recent developments, cocoa trading also experienced a phase of reorganisation and consolidation. The United Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) noted as early as 2004 that a few large multinationals had begun to dominate cocoa trading, processing and manufacturing, ‘having taken over, replaced, or merged with the smaller companies engaged in trading physical cocoa’ (UNCTAD 2004, 11). At the turn of the century, the three largest cocoa-processing companies (ADM, Barry Callebaut and Olam) accounted for some 40–50% of world grinding. By 2015, 75% was controlled by just two companies (Barry Callebaut and Olam), after Olam’s acquisition of ADM’s cocoa processing business a year earlier (VOICE Network 2015). In terms of the consolidation of chocolate manufacturers, around 17 firms controlled half of the world market in 2000 (UNCTAD 2004). In the wave of reorganisation post-2008, many of these firms either merged with or were acquired by competitors. Kraft and Cadbury merged together to become Mondelēz, Ferrero acquired Oltan, Mars acquired Grupo Turin and Ferrero completed another acquisition, this time of Thorntons (SEO Amsterdam Economics 2016). As a result, just under half of the global chocolate market in 2015 was controlled by only four firms (Mars, Mondelēz, Nestlé and Ferrero).

Whilst the phases of liberalisation and reorganisation that altered the cocoa market system are not perhaps as well defined as those in the coffee market system, the two systems have experienced similar changes over the last five decades. During the 1960s, the 1970s and much of the 1980s, trading was governed through international supply management agreements and national marketing structures, and re-export mark-ups were only marginally higher than export mark-ups. During the 1990s and early 2000s, international supply management agreements and national marketing structures were dismantled as trading was liberalised, and re-export mark-ups grew to become significantly higher than export mark-ups. In the years following the 2008 financial crisis, trading, processing and manufacturing were concentrated intensely, and re-export mark-ups increased further versus export mark-ups.

European policy

The market-systems changes that have taken place in recent decades have been largely favourable to coffee and cocoa importing and re-exporting nations. The suppression of international commodity agreements and the dismantling of national marketing structures, as well as the concentration and diversification of European agri-business are widely considered to have been key drivers of the ongoing crisis for Africa’s coffee and cocoa producers. However, these changes have generated positive impacts elsewhere, particularly in successful coffee and cocoa re-exporting countries in Europe. The ICO’s 2009 Annual Review showed that coffee added $31 billion to the economies of the nine leading importing nations, a figure more than double the total export earnings of all 40 ICO-registered producing nations that year (ICO 2009). In relation to these developments, this section will discuss the role of the European Union, as the public institution responsible for governing the terms of entry into the world’s largest single consumer market for commodities, and the Swiss government, as the public institution governing one of the most important single-country coffee and cocoa trading hubs.

The European Union

There were many reasons for the end of the major international commodity agreements, but the lack of EU support for their continuation was one of the most important. Control of the coffee and cocoa markets ceased because of the practical difficulties associated with designing agreements that benefited all producing countries equally, and the EU blocked efforts among producing countries to revise agreements that were approaching expiry (Gilbert 1996). Quota levels within the coffee agreement, for example, were disputed intensely among producing countries, and many wanted to address perceived bias towards Robusta producers (e.g. Brazil). The EU opposed the US Congress’ attempts to redistribute the quotas in favour of high-quality Arabica producers (e.g. Colombia). As the fourth ICA expired in 1989, a consensus regarding the make-up of quotas could not be reached, and a new agreement was not put in place. In terms of national-level supply management, coffee and cocoa cooperatives and marketing boards were highly dependent on financing from the EU and the World Bank, much of which was withdrawn by both institutions in the 1990s (UNCTAD 2004).

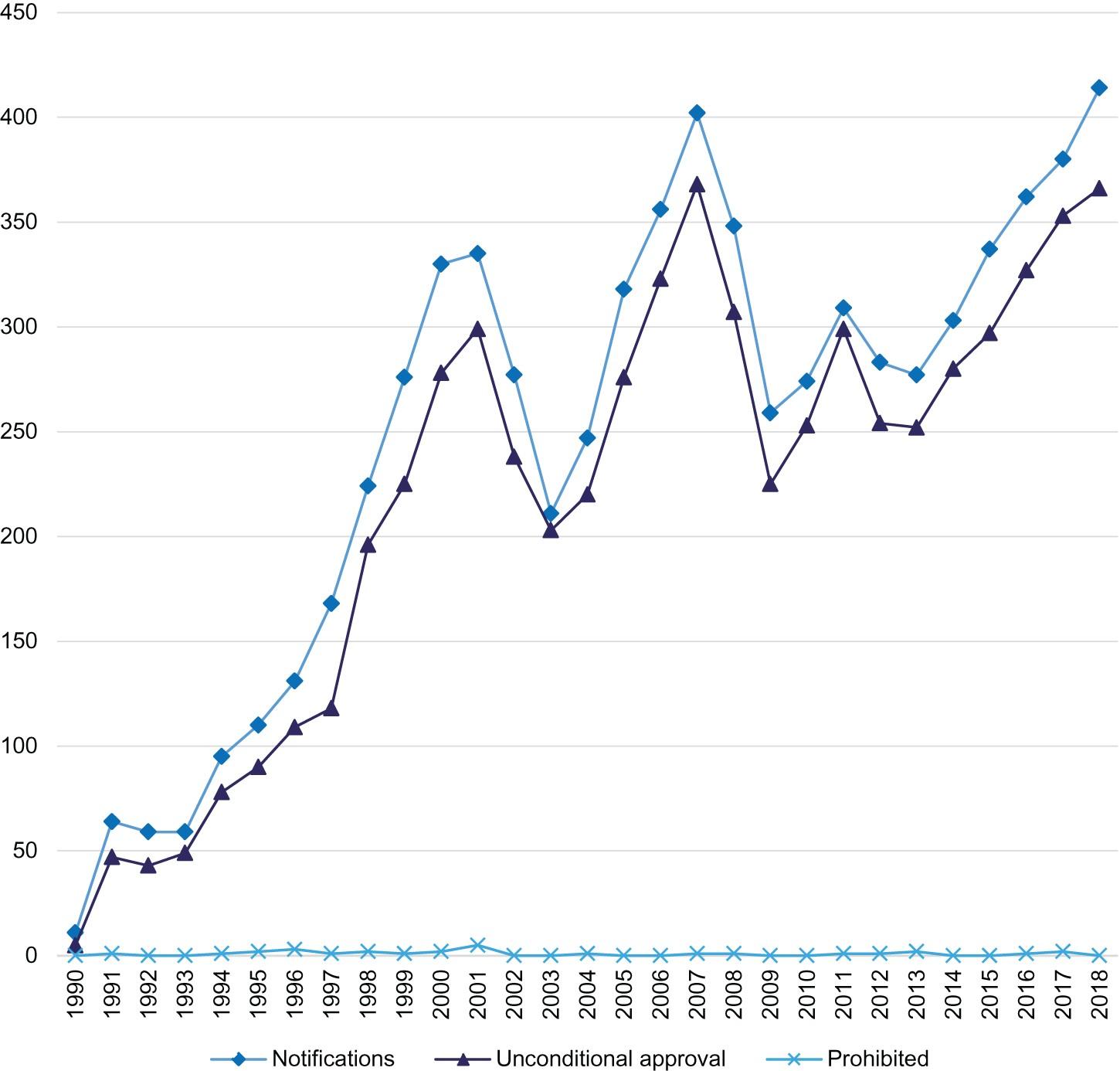

The link between EU policy and the recent concentration and diversification of its agrifood sector is perhaps more explicitly clear. The EU’s indulgence of its commodity multinationals has been highlighted by several high-profile civil society organisations, including the Fair-Trade Advocacy Office (FTAO), which states that EU competition policy has played ‘a key role in the shaping of modern-day global food supply chains that are characterised by massive imbalances of power; an unfair sharing of value, and the continuous struggle to produce cheap food’ (FTAO 2019, 2). This is partly because, as Figure 1 shows, the European Commission has granted unconditional approval to almost all major merger notifications received since 1990.

European Commission merger notifications and decisions, 1990–2018. Source: European Commission (2015).

The decisions to approve these mergers and acquisitions have often been justified in the interest of the consumer (De Schutter 2010), and the FTAO notes that the common interpretation of EU competition law rarely considers issues beyond the availability of a wide range of cheap consumer products (FTAO 2019). A prominent example of this was the European Commission’s decision to approve the 2015 merger of Cargill and ADM only conditionally, because it ‘risked increasing chocolate prices for customers’ (European Commission 2015). However, this justification does not reflect the extent to which these decisions have benefited industry. Whilst consumer prices have largely remained consistent, the mark-ups and profits received by multinational coffee roasters and chocolate manufacturers have increased by 11–12% in only the last 15 years (Oxfam International 2018).

Switzerland

The Swiss government is important to consider because it hosts many of these multinational coffee roasters and chocolate manufacturers and, whilst it is not the leading European re-exporter of coffee by volume, its average export earnings dwarf those of any other European country. Between 2000 and 2010, Switzerland earned an average of $11 per kilogram of coffee exported (International Coffee Organization 2012); a remarkably high figure even in the context of other leading coffee re-exporters, such as Belgium ($3 per kg), Germany ($3.11 per kg) and the Netherlands ($4.03 per kg). Curiously, Switzerland’s coffee industry has not always been so competitive. Between 1965 and 1989, Switzerland earned an average of $40 million per year through the re-export of bulk coffee products, less than 10% of the £468 million a year earned on average between 2000 and 2010 (ICO 2012). Many of Switzerland’s other commodity industries have experienced similarly spectacular levels of growth since the 1990s (Dobler and Kesselring 2019): 60% of all metals, 50% of coffee, 50% of sugar, 35% of grains and 35% of crude oil are now all traded via Swiss companies (Lannen et al. 2016). Five of the largest Swiss companies are now commodity traders (Cargill, Glencore, Mercuria Energy Trading, Trafigura and Vitol), and these industries now generate more of Switzerland’s gross domestic product than banking or tourism (Ibid.).

The exact role that Switzerland played in the suppression of international commodity agreements and national marketing structures beyond its endorsement of structural adjustment is unclear. However, research has shown that, even by European standards, Switzerland’s response to the concentration of power within its coffee and cocoa sectors was notably lax. Its national competition authority, whose officials are appointed by the executive rather than the legislature, is not required to publish its decisions or even justify them (Zweifel 2003). Moreover, Switzerland’s different cantons each have jurisdiction over their own corporate tax rates (Shaxson 2011), and they compete with each other to offer multinational traders, processors and manufacturers the lowest and most favourable tax regimes. ‘The global average for taxes on earnings, capital tax and property tax combined is 29%; the Swiss average is 16.6%, while some cantons stay below 12%’ (Dobler and Kesselring 2019, 235). Switzerland’s re-export boom is therefore indicative of the link between competition, regulatory and corporate tax policies that indulge multinationals and commodity trade surpluses.

Conclusion

There are many reasons for the levels of poverty experienced by Africa’s coffee and cocoa producers, such as the typically small size of farms, uncertainty of land tenure, relatively low levels of productivity, lack of infrastructure and restricted access to market information. European traders, processors and manufacturers of coffee and cocoa products, by contrast, enjoy unrestricted access and geographic proximity to the world’s largest consumer markets, secure access to low-interest finance and insurance, highly skilled workforces, and flexible labour markets through which workers can be hired on low-cost, short-term contracts.

Whilst these competitive advantages have largely remained consistent, production mark-ups have shifted to the processing and manufacturing levels of the supply chain, prompting a crisis for producers and a simultaneous boom for European re-exporters. Therefore, in addition to well-documented changes in technology, communications, consumer preferences and global production potential, the ongoing crisis faced by Africa’s coffee and cocoa producers can be attributed to the use of competition and foreign policy tools to suppress the management of supply at the international and national levels, and to indulge the interests of the increasingly monopolistic European agri-food sector.

There is a widespread perception that the indulgence of the European agri-food sector is motivated primarily by the need of European governments to ensure the availability of a wide range of cheap food products for European consumers. However, the commodity re-export boom has also become an important source of national trade surpluses, jobs and public revenues for many European countries. Those interested in tackling the levels of poverty experienced by Africa’s commodity producers should therefore direct their efforts towards addressing concentration in processing and manufacturing, and towards supporting the effective management and coordination of global supply, to scale up the bargaining power of producers and ensure satisfactory minimum prices for all major agricultural commodities. When confronted with rising market concentration, profits, mark-ups and market power, European governments, as the gatekeepers of the most lucrative consumer markets, can intervene through a variety of competition enforcement tools. Convincing them to do so will require a collective advocacy effort capable of rivalling the interests of the growth-driving corporate sector.