Introduction

Nigeria’s credentials as a major player in the global oil economy are challenged by a number of paradoxes that undermine the advantages of its hydrocarbon endowments. These paradoxes include a serial incapacity to manage oil wealth, widespread elite predation and looting of the economy, extreme poverty, insecurity and dependence on imported refined petroleum products to meet national needs, and have been labelled collectively as the resource curse (Watts 2004; Omotola 2009; Courson 2011; Akpomera 2015; Osaghae 2015). According to the Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), the total financial flows associated with the oil and gas sector between 1999 and 2016 totalled US$614.61 billion with the revenue flows to the Federation Account being US$579.65 billion (NEITI 2020). Yet despite these enormous financial inflows, Nigeria occupies a dominant position on the global poverty map. The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) estimates that 40.09% or 82.9 million Nigerians live below its poverty line of N137,430 (US$381.75) a year (National Bureau of Statistics 2020).

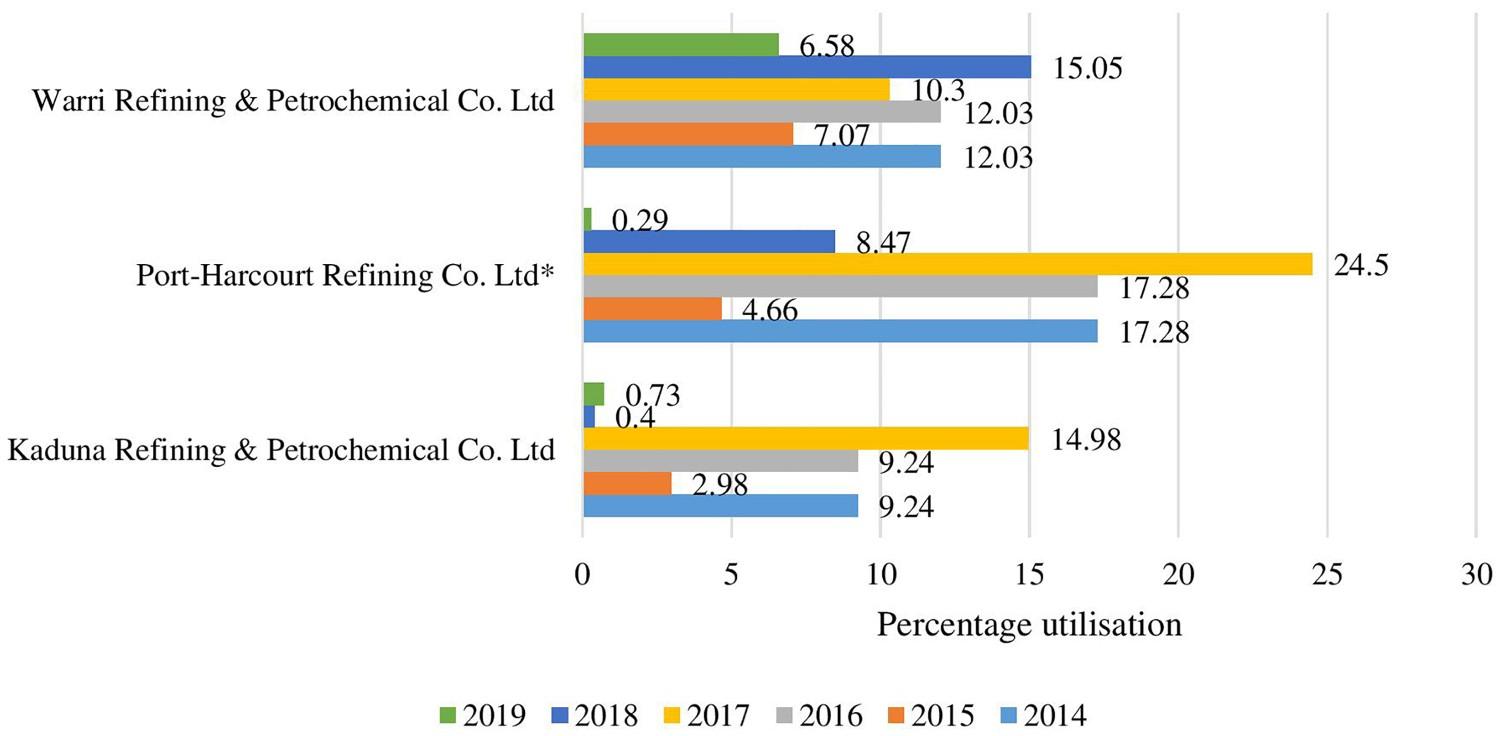

Nigeria has a current potential crude oil production capacity of 4 million barrels per day (mb/d), but even following the success of the amnesty programme and the substantial reduction in the incidences of conflicts and violence against the country’s oil interests by the Niger Delta youths, the country’s actual daily production has averaged just over 2 million mb/d (NNPC 2019). Any recovery in the upstream sector is not replicated in the downstream sector, which is more or less comatose. For instance, in addition to the inadequacy of Nigeria’s total refining capacity of 445,000 barrels per day (bpd), considering its estimated population size of 208.28 million and attendant domestic requirements, the four state-owned refineries are nearly non-functional (NNPC 2019; OPEC 2020). The consolidated average capacity utilisation of these refineries in 2018 and 2019 was 5.98% and 1.90%, respectively (NNPC 2019). With this scenario, Nigeria relies exclusively on imported refined petroleum products to meet domestic demands. The country imports at least 91% of its petrol and other refined petroleum products (BudgIT 2019).

The supply gap created by the inefficiency in the country’s downstream sector opened the door for artisanal refining, with its attendant security and economic challenges to the country. Artisanal refining operates at the intersections of oil theft, environmental degradation and targeted violence on oil installations. Variants of research have focused on the interplay of artisanal refining and environmental degradation (Moses and Tami 2014; Yabrade and Tanee 2016; Bebeteidoh et al. 2020) as well as its socio-economic contributions to solving a national problem, which the state has demonstrated a serial incapacity to deal with (Obenade and Amangabara 2014; Asawo 2016; Umukoro 2018; Adunbi 2020). However, the political economy dimension has been understudied, which is what this briefing aims to bridge. The data for this paper were extracted from 20 key informants to address the broader contradictions of Nigeria’s oil economy. The key informants were selected based on the criteria of their established knowledge of Nigeria’s oil and gas sector, direct and indirect involvement in the oil economy, and their capacity for analytical assessment of the various aspects of the oil and gas sector. Additionally, the data generated from the key informants were complemented with materials from diverse archival sources. This briefing is divided into six sections. Following this introduction, the second section examines the developmental trajectory of artisanal refining. Section three provides theoretical insights and the fourth section analyses the driving forces of artisanal refining. Section five, before the conclusion, explores the tangibility of state policy on artisanal refining.

The development impetus and trends in artisanal refining

Artisanal refining is illegal in Nigeria. The basis for its illegality is the extant legal provision in the Hydrocarbon Oil Refineries Act, Cap H5, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria (LFN), 2004, which outlaws individuals from refining any hydrocarbon oils except in a registered, recognised and licensed refinery (Okpanachi 2017). By reason of this illegality, artisanal refineries are part of Nigeria’s sprawling underground oil economy. The underground oil economy involves criminal economic transactions that cover such illegal and criminal activities as pipeline vandalism, piracy, oil bunkering or theft, targeted destruction of oil facilities, small arms and light weapons proliferation, hostage taking, kidnap-for-ransom and artisanal refining (Murphy 2013; Iwilade 2014; Onuoha 2016; Ezirim 2018).

Although the earliest form of artisanal refining is linked to the Nigerian civil war, its contemporary manifestation and entrenchment is strongly linked to the era of militancy (Naanen and Tolani 2014; Umukoro 2018). It has been contended that the appeasement of the militants with amnesty and their subsequent surrender in 2009 marked the watershed for artisanal refining (Nwozor 2010; Obenade and Amangabara 2014). The erstwhile militants who had developed the knowledge of refining put it to use due to the enabling environment that promoted its deployment. The enabling environment consisted of the initial inaction of the government towards its stoppage, availability of crude oil, thriving network of oil theft, huge economic rewards, expansive and thriving market, incapacity of state refineries due to inefficiency, and perennial shortages of refined petroleum products (Obenade and Amangabara 2014; Social Action 2014; Umukoro 2018).

The initial publicised emphases of sundry militant groups had revolved around the demand for ‘restitution for the environmental damage wrought by the oil industry, greater control over oil revenues for local government, and development’ (Omeje 2006, 44). However, they leveraged their access to violence in the face of institutional weaknesses to engage in the accumulation of wealth through clandestine criminal activities. Thus, in the face of economic disempowerment, the underground oil economy provided the Niger Delta youths with the mechanisms to procure their instruments of violence as well as to ‘construct their own meanings out of an often disempowering context’ (Iwilade 2014, 573). A major way that Niger Delta youths have been able to construct economic meaning out of Nigeria’s oil economy is through artisanal refining.

Although the amnesty programme provided pecuniary benefits to the ex-militants, these benefits were inadequate compared to their earlier access to wealth through multiple criminal channels (Aghedo 2013). This disparity in earnings underpinned the efflorescence of oil theft and associated artisanal refining. Apart from the mainstream insurgent groups such as the Niger Delta Peoples Volunteer Force (NDPVF), Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and the Niger Delta Vigilante (NDV), among others (Murphy 2013; Abang 2014; Lenshie 2018), there were also many fringe militant groups. The dismantling of the insurgent groups in the wake of the amnesty programme created multiple unstructured nodes of rivalry among the youths in the artisanal refining subsector. The youths engaged in an intense quest to gain greater access to, and a foothold in, the underground oil economy. This resulted in increased incidences of pipeline vandalism, which was necessary to secure access to feedstock for their artisanal refineries. In order to roll back the associated economic loss while defusing the competition and tension from these activities, the security of oil facilities in the Niger Delta was further privatised. The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) and the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) awarded various packages of yearly surveillance and protection contracts worth millions of dollars to four key ex-militant leaders, namely Government Ekpemupolo (Tompolo), Asari Dokubo, Ateke Tom and Ebikabowei Victor Ben (Boyloaf) as a means of dealing with the situation (Aaron 2015; Ezirim 2018). However, this arrangement neither stemmed the tide of oil theft nor stopped artisanal refining.

Artisanal refineries developed in deference to two-pronged logics of scarcity. On the one hand was the logic of scarcity imposed by environmental degradation and the associated contraction in livelihood opportunities. Although the amnesty programme provided stipends, the imperative of surviving at a scale higher than what was offered encouraged the pursuit of alternative means for income generation. The key informants pointed out that a major flaw in the policy of amnesty was its seeming disconnect with the related push factors that spawned violence as a tool of choice among the youths. Thus, despite the success of the amnesty programmes in drastically downscaling violence in the Niger Delta region, many of the initial grievances that led the youths to take up arms, such as socio-economic marginalisation, youth unemployment, poverty and environmental degradation, were not systematically addressed. This left room for violence by other means (Aghedo 2015; Nwozor, Audu, and Adama 2019).

On the other hand was the logic of scarcity catalysed by the disconnect between demand and supply. The gap still exists, and is motorised by the inefficiency of Nigeria’s four state-owned refineries. Thus, artisanal refining emerged to take advantage of, and contribute to, addressing a national need. The relevance of artisanal refining in the political economy of Nigeria lies in its contributions to the satisfaction of local demands for refined petroleum products in the face of an unreliable national supply system.

Artisanal refining is a locally contextualised strategy for refining crude oil (Umukoro 2018). It involves a small-scale or subsistent distillation of crude petroleum over a specific range of boiling points, to produce useable petroleum products ranging from premium motor spirit (PMS) to household kerosene (HHK) to automotive gas oil (diesel) (Social Action 2014; Umukoro 2018). As has been argued in some quarters, artisanal refining represents a new frontier in the struggle for the capture of oil in Nigeria (Adunbi 2020). The new frontier demystifies the refining exclusivity of big corporations and underscores domestic innovativeness and the relevance of traditional know-how (Umukoro 2018; Adunbi 2020). The major attraction of artisanal refining is its reliance on traditional knowledge and skills rather than advanced or high-end technology. Umukoro (2018) avers that artisanal refineries are basically labour intensive due to their unsophisticated nature. The fact that they are simple and unautomated presupposes that they are not particularly expensive to acquire and set up. The relatively low capital requirement to set up artisanal refineries has made informal indigenous participation possible, underscoring their proliferation and ubiquity in the Niger Delta region.

Theoretical insights

Artisanal refining fills a number of gaps created by a combination of state inefficiencies. These gaps include the huge disparity in the relationship between domestic supply and demand of refined petroleum products, youth unemployment, exclusion from the oil economy and poverty. Adunbi (2020) suggests that artisanal refining is at the epicentre of a ‘new oil frontier’. The involvement of youths in the politics of crude oil governance through artisanal refining has created a new form of power relationship that may have impacts on general decision-making in the region.

This briefing is anchored in critical political economy to evaluate the various stakeholders and their roles in the architecture of Nigeria’s oil economy, especially within the context of the intersections of the underground oil economy and the catalysing influence of conflict and violence. Oil production activities have tended to create an economic vacuum in the oil-bearing communities of the Niger Delta. This economic vacuum is essentially caused by the adverse environmental impacts, which dislocate the communities from their traditional patterns of livelihood and deny them tangible economic benefits. This constitutes a problem not just because of the nonchalance of the government and oil companies to address them but their seeming intractability due to years of neglect, spawning what has been referred to as ‘conflict economy’ (Ebiede 2017, 14).

Critical political economy is illuminating in a number of ways. It provides an insight into the forces at play in the intractability of the problem of oil production activities and its connection to artisanal refining. These problems span the spectrum that includes the deployment of substandard operational procedures by oil companies, elite corruption, the exclusion of communities from decision-making processes, environmental degradation and relative neglect of oil-bearing communities, which is often mirrored by the inadequacy of institutionalised interventionist efforts (Acey 2016). Critical political economy frames the inevitably asymmetrical power relationship between the people, government and oil corporations in dealing with the challenges and fallouts of the oil economy and illuminates how this birthed and sustained insurgency in the region. The approach recognises the dynamic, nonlinear and heterogeneous variables at play, providing integrated insights into how class alliance – which transcends ethnic lines but is welded together by economic interests – underpins the landscape of Nigeria’s underground oil economy that paves the way for the flourishing of artisanal refining.

The major drivers: Nigeria’s artisanal refining scenario

Key informants were interviewed broadly on Nigeria’s underground oil economy and specifically on the drivers of artisanal refining. Two interrelated questions concerning the major drivers of artisanal refining were posed. These questions centred on: (i) the factors they considered to underpin the justification for artisanal refining, and (ii) whether the seeming ineffectiveness of state responses to feelings of exclusion and marginalisation by oil-bearing communities contributed to the spread of artisanal refining. Their responses identified interrelated themes that motorised artisanal refining. These included youth unemployment and the logic of survival, scarcity of refined petroleum products arising from state inefficiency, predatory elite tendencies manifesting in oil theft syndrome, and the psychosocial sense of ownership and entitlement.

The key informants agreed that one of the factors driving artisanal refining is the pervasive youth unemployment in the region and nationally. In other words, the sustaining logic of artisanal refining is that it can help roll back youth unemployment and contribute to the imperatives of human security and survival. The Niger Delta region is reputed to have the largest wetland in the world after the Pantanal in South America and the Mississippi in North America. This wetland helped shape traditional livelihoods in the region: hunting, farming and fishing (Mai-Bornu 2020). However, environmental degradation arising from oil production destroyed these means of livelihood. According to Onyena and Sam (2020, 4), ‘ecological impacts arise from produced water, drilling fluids, cuttings and well treatment chemicals, wash and drainage water, sanitary and domestic wastes and, spills and leakages.’ The key informants observed that the combined impacts of oil production included the destruction of the traditional means of livelihood, attendant deskilling of the population due to induced changes in their livelihood pursuits, and unemployment. The key informants contended that the absence of a secure material base in the face of perceptions of exclusion, neglect and marginalisation underpinned the anti-state agitations that evolved from protest marches to symbolic declarations of the population’s rights over oil resources and demand for resource control, to insurgency, and then to various forms of criminality. Artisanal refining is an offshoot of these developments, and its major sustaining logic is the lucrativeness of the enterprise.

Another factor that has favoured artisanal refining is the scarcity of refined petroleum products arising from the inefficiency of state-owned refineries. Nigeria has four refineries that are owned by the federal government, and one refinery owned by private interests. While the state-owned refineries have a combined nameplate capacity to refine 445,000 barrels per stream day (bpsd), the one owned by private interests has a capacity for 1000 bpsd. Data have shown that this combined refining capacity is inadequate to meet the daily domestic requirements for refined petroleum products even if they should operate at optimal levels. According to BudgIT (2019), the current domestic refining capacity can only yield about 33.7 million litres of petrol daily, in contradistinction to the country’s daily requirement of 51.6 million litres. However, the refineries have been producing at a scandalously low level for a very long time, making the country overly dependent on imported refined petroleum products (see Figure 1). It is estimated that Nigeria imports at least 91% of its petrol and other refined petroleum products (BudgIT 2019). However, anecdotal evidence suggests that Nigeria’s importation profile could be higher, considering that smuggling of these products to neighbouring West African countries is a flourishing multimillion-dollar business that contributed to the closure of the country’s borders in 2019 (Nwozor and Oshewolo 2020).

A six-year comparative capacity utilisation of Nigerian refineries. *The entry for Port-Harcourt Refining Co. Ltd captures two refineries. Source: NNPC (2019).

The inefficiency of the refineries has left a gaping supply hole in the domestic demand architecture of Nigeria. The key informants agreed that this gap, coupled with dependence on importation, has resulted in a perennial cycle of shortages, price hikes, questionable subsidies and allegations of corruption. The serial poor performance of the state-owned refineries has had serious negative impacts on the Nigerian economy. According to BudgIT (2019), Nigeria incurred a cumulative loss of N159.6 billion or US$441.67 million (at the exchange rate of N360/US$1) in the 2017 and 2018 financial years from the inefficient operations of its state-owned refineries.

Artisanal refiners rely on the underground oil economy for their operations and survival. The underground oil economy is driven by predatory elite tendencies manifesting in oil theft syndrome (Akpomera 2015). The key informants contended that although stolen crude oil serves as the feedstock for artisanal refineries, it is only one small aspect of the complex network of oil theft. This view is corroborated by the data from NEITI that indicated a loss of about 22 million barrels estimated at US$1.35 billion in the first six months of 2019 (NEITI 2019). This quantum of crude oil loss could not have been driven solely by artisanal refining. The estimate of crude oil that makes its way to artisanal refiners as feedstock has been put at 25%, with the remaining 75% finding its way to the international oil market (SDN 2015). Thus, oil theft has both domestic and international dimensions (Katsouris and Sayne 2013; Ezirim 2018). Notwithstanding the nonexistence of a credible national database for oil production, estimates of crude oil losses due to oil theft range between 150,000 and 400,000 barrels per day (bpd). According to NEITI, between 2009 and 2018, Nigeria lost more than 505 million barrels of crude oil and 4.2 billion litres of petroleum products valued at US$40.06 billion and US$1.84 billion, respectively (NEITI 2019). The magnitude of this oil theft indicates that it is due to big business with likely entrenched networks in the top echelons of the country’s bureaucratic system (Asuni 2009; Katsouris and Sayne 2013).

The failure to deal with the fallout of oil production activities in the Niger Delta has contributed to an increase in criminality. It is true that interventionist institutions were created at different periods and that Niger Delta states have been receiving a monthly payment of 13% derivation since 1999 to deal with development issues in the region. However, the Nigerian state failed to enforce accountability in the management of these resources. Additionally, no serious effort was made to punish corrupt officials. The two serious indictments, namely those of Diepreye Alamiesiegha of Bayelsa State and Jame Ibori of Delta State, came from the UK (Nwozor et al. 2020). Within Nigeria, the corruption exposés concerning Niger Delta leaders by various entities, including international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and the anti-graft agencies, generated little beyond a short-term media stir (Newsom 2011).

State failure to enforce accountability, the allocation and circulation of oil blocks among the elites and the outright embezzlement of state funds by elites engendered a psychosocial sense of ownership and entitlement among Niger Delta youth. It emboldened them in what the agents of the state have termed opportunistic criminality (Mai-Bornu 2020). The general feeling of the Niger Delta youths who are involved in one form of criminal activity or another is that they are not doing anything illegal as the oil belongs to them. The basis for this groupthink is the role of oil rent in the wealth status of most Nigerian elites. In 2013, 83% of Nigeria’s oil blocks allegedly belonged to northern elites. The weak response of Nigeria’s Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) to this weighty allegation was that ethnicity was never a criterion for the award of oil blocks (Vanguard 2013).

The key informants contended that the psyche of entitlement accounts for the number of youths who are actively involved in artisanal refining as well as their resistance to the efforts of security agencies to dislodge them. Artisanal refineries have become an integral component of the local economy across many communities in the Niger Delta region (SDN 2015). Although there is no authenticated data about the number of youths operating in the artisanal refining enclave, anecdotal evidence and other estimates indicate that direct and indirect beneficiaries number in the hundreds of thousands. However, Naanen and Tolani (2014) estimate that some 26,000 people were operating in the artisanal refining enclave in 2014. Artisanal refining generates billions of naira in the local economy of the Niger Delta region. While Naanen and Tolani (2014) estimate that oil theft and artisanal refining are worth US$9 billion, BudgIT (2019) estimates that artisanal refining alone is worth N8.4 billion (US$23.33 million) per month. Thus, artisanal refining represents the most valuable and lucrative source of local employment and economic empowerment in rural communities of the Niger Delta region.

Is there any tangible state policy on artisanal refining?

The policy option adopted by the Nigerian government to deal with the problem of artisanal refining has been the deployment of military force under the auspices of the Joint Task Force (JTF). The JTF is an amalgam of various arms of the Nigerian military and the police. The JTF was initially conceived as a counterinsurgency force. However, with the success of the amnesty programme, it was refocused in 2012 to fight oil-related and maritime crimes as well as to protect Nigeria’s oil installations and facilities (Courson 2011; International Crisis Group 2015; Bebeteidoh et al. 2020).

The JTF has been active in fighting the proliferation of artisanal refineries in the Niger Delta region. Its strategy essentially consists of destroying identified illegal refineries by setting them ablaze. The JTF has been destroying illegal refineries on a regular basis since 2009, when it reportedly destroyed 600 illegal refineries. At the time, the JTF estimated that about 1500 illegal refineries were operating in the Niger Delta (Naanen and Tolani 2014). According to SDN (2015), the JTF reportedly destroyed a total of 4349 illegal oil refining camps in 2012. In the same vein, it burnt ‘1,951 artisanal refineries, 82 tanker trucks and 36,760 drums of illegally refined fuel’ in 2013 (International Crisis Group 2015, 12). In September 2017, the Nigerian navy destroyed 1000 local refineries in the Niger Delta region (Bebeteidoh et al. 2020). However, the lucrativeness of the venture ensured that destroyed refineries were quickly rebuilt. According to SDN (2015), it took between 2 weeks and 3 months to rebuild. The cost of such rebuilding was often low, at between 3% and 7% of their profit margins.

The challenges posed by the seeming intractability of destroying artisanal refining led to the consideration of alternative solutions by the Nigerian government. In 2017, the Nigerian government, through the vice president, Yemi Osibajo, seemingly made a commitment to legalise the operations of artisanal refiners through the adoption of a modular refineries model (Nwozor 2020). The thinking was that youths of the Niger Delta region would be empowered to own modular refineries as a trade-off to artisanal refining. The impression created by the promise of modular refinery was that artisanal refiners would form cooperatives to be able to access the financial backing necessary to obtain licences to refine. To date no government policy has been unveiled about how to facilitate the transition of artisanal to modular refineries.

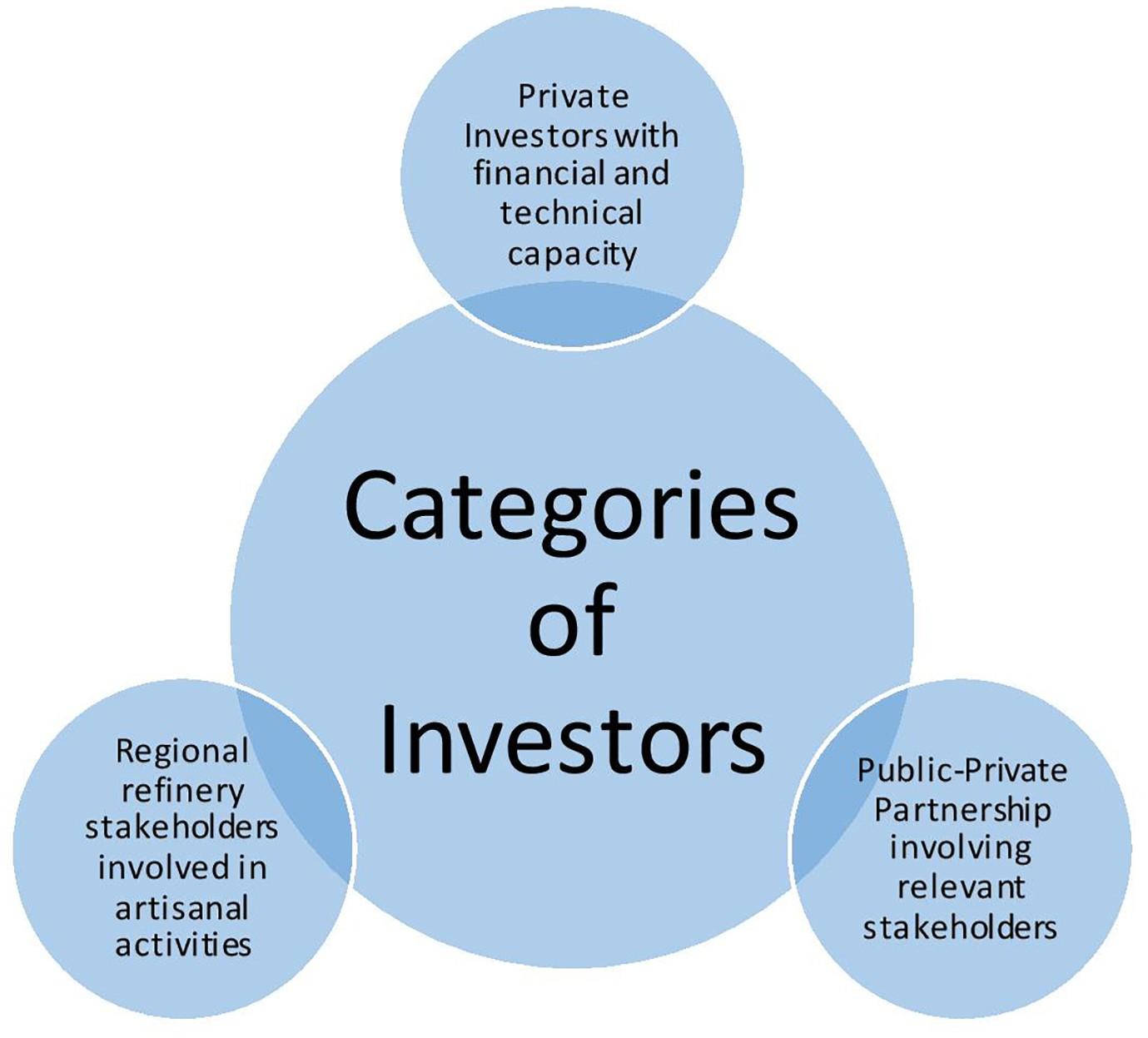

A document from the Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources entitled ‘General requirements and guidance information for the establishment of modular refineries in Nigeria’ recognised artisanal refiners in the category of prospective investors in the country’s modular refinery landscape (Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources 2017). Figure 2 captures the envisaged categories of investors in the modular refinery model.

Categories of investors in the modular refinery model. Source: Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources (2017).

The take-off of the modular refinery model in Nigeria has been an uphill task and a slow work in progress. In 2002, 21 companies were granted licences to establish (LTEs) with a validity period of 18 months. In 2004, 17 of these companies were awarded approval to construct (ATCs). However, only one of them, Niger Delta Petroleum Resources (NDPR), has been able to come on stream, with an installed refining capacity of 1000 bpd for automotive gas oil (diesel) (Nwachukwu 2016). The contributions of NDPR, which began its refining operations in 2011, were hailed by Nigeria’s DPR as ‘a veritable benchmark on efficient management of fringe assets … [and] a pointer to the potentials of emerging policy on modular refineries as a solution for the current domestic refining gap’ (Department of Petroleum Resources 2015, 34).

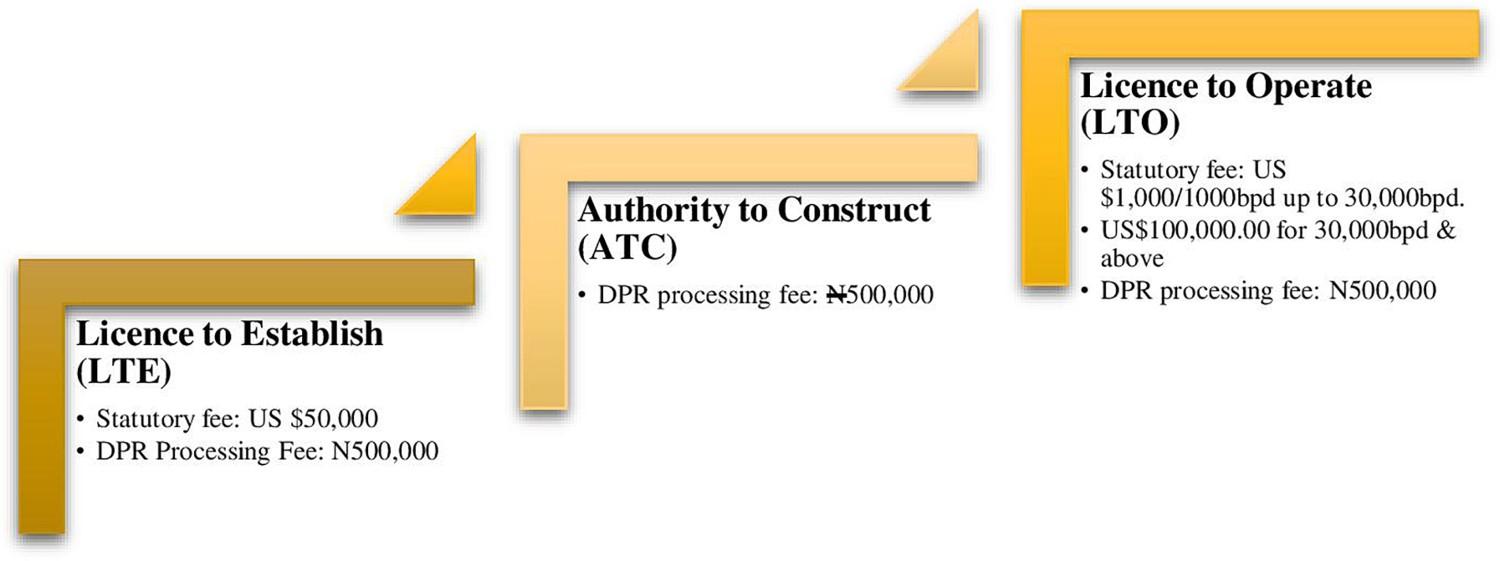

The policy on the establishment of modular refineries does not currently favour artisanal refiners. Although the attraction of modular refinery lies squarely in its cost efficiency in comparison to conventional refinery, the cost of its establishment is relatively prohibitive. Artisanal refiners cannot afford the cost of setting up a modular refinery without guaranteed financial backing. There are two interrelated costs, namely statutory and take-off costs, both of which run into the millions of dollars. These costs are in addition to providing a ‘detailed financial plan with Proof and source of funding … ’ (Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources 2017) as a condition to be met before consideration for licensing. Figure 3 provides an insight into the various statutory costs for licensing a modular refinery.

Costs of approval for the various stages in the establishment of modular refinery. Source: extracted from Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources (2017). DPR: Nigeria’s Department of Petroleum Resources.

Modular refineries have refining capacities that range from 1000 to 30,000 bpd. The cost of setting up a modular refinery depends on its capacity. The key informants and supporting documents indicated that the refining capacity and the combination of products that a modular refinery has been configured to produce would determine the range of its cost. As Mamudu, Igwe, and Okonkwo (2019) noted, modular refineries come in various packages and degrees of sophistication, notwithstanding that they perform the three basic crude oil refining processes of separation, conversion and treatment. Thus, the more the owners of a modular refinery configure it to refine at a given time, the costlier it would be to set it up. It is estimated that setting up a modular refinery will cost between US$10 million and US$250 million (Adeosun and Oluleye 2017).

Considering the profile of licensees for modular refineries, it would appear that the focus of Nigeria is elitist, with scant concrete attention paid by relevant government agencies to integrating artisanal refining in their plans and projections. The implications of state ambivalence to artisanal refining are that its negativities, such as being part of the drivers of oil theft and environmental degradation, could deepen the contradictions relating to power relationships among artisanal refiners, oil-bearing communities, oil companies and the state. Additionally, this might have a direct impact on the viability and investment prospects of modular refineries. Thus, beyond the paternalistic pronouncements about integrating artisanal refining into the modular refinery model, the real motive could be to unclutter the operational arena of domestic refining, decelerate the prospects of combative reactions and thus attract private investment in the sector. The ownership mind-set among oil-bearing communities has led to social organising in the form of an umbrella organisation named the Artisanal Oil Refiners Association of Nigeria (The Sun 2020). This organisation has held consultations with the Senior Special Assistant to the President on Niger Delta Affairs, Senator Ita Enang, with the goal of transitioning its members’ operations to the modular refining model. Neither the modality for achieving this goal nor a clear policy direction has yet evolved.

Conclusion

Artisanal refining has become not only an entrenched business in the Niger Delta but also an integral component of the local economy across many communities. It contributes enormously to the overall well-being of the region (SDN 2015), representing the most valuable and lucrative source of local employment and economic empowerment in rural communities of the Niger Delta region. This notwithstanding, the Nigerian state views the operations of artisanal refiners as illegal, criminal and prejudicial to the Nigerian economy and the environment. The anticipated silver bullet was the implementation of the government’s promise to transform artisanal refining into modular refining. However, artisanal refiners do not have the financial strength to set up modular refineries. The various Niger Delta states and interventionist institutions should evolve a workable and sustainable funding arrangement to facilitate a transition from artisanal to modular refineries.