Introduction

The recent global financial crisis sparked renewed debates, both within academia and policy-making circles, about regulating highly mobile cross-border money-capital flows. A particular type of policy tool has received considerable attention: capital controls (CC). Within mainstream economics and policy-oriented circles (including policy-makers in central banks, finance ministries and international organisations such as the IMF and the G20), there has been a growing recognition that unregulated cross-border money-capital flows can considerably disrupt capital accumulation, and debates have accordingly focused on the potential role and effectiveness of temporary CC in limiting the destabilising potential of those flows, while maintaining a long-term commitment to an open capital account and free capital mobility (IMF 2012). By contrast, the Left (including organised labour, progressive economists and civil society organisations) has been largely critical of capital-account liberalisation, and has denounced its detrimental effects in terms of constraining policy options for development and long-term industrial development (Chang and Grabel 2004; Epstein 2012; Gallagher 2015). Consequently, there has been a growing consensus on the Left that CC can play a key role in designing more progressive and development-friendly forms of financial governance, and in empowering labour vis-à-vis capital.1 While those debates are welcome, participants have to a large extent refrained from engaging in historical analyses of CC grounded in the social relations of production prevailing in specific national contexts. This is particularly problematic, given that CC are not neutral, technical measures which fulfil similar objectives irrespective of where they are implemented. By contrast, CC have historically played an important role in broader class-based strategies and in sustaining particular forms of capital accumulation, as Soederberg (2002, 2004) has shown with the examples of Malaysia and Chile, and as I have shown in the case of Brazil (Alami 2016). In fact, the lack of critical analyses of CC sensitive to class dynamics is quite surprising, given the now-widespread view on the Left that curbing the power of capital over labour will involve CC. The starting point of this article is therefore that if progressive forms of CC are to be designed in the future, it is necessary in the first place to understand the role and function that CC have played in particular national contexts, and to uncover the class dynamics associated with them. This is especially important in those countries which have a long history of CC, and where there have recently been some debates on implementing new forms of CC, like South Africa.

Indeed, during the post-global financial crisis boom in private capital flows to South Africa (late 2008–mid 2011), a variety of social actors including organised labour (the Congress of South African Trade Unions [COSATU] and the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa [NUMSA]), progressive economists and intellectuals on the Left (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011a, 2011b; Mohamed 2012; McKenzie and Pons-Vignon 2012), some segments of the manufacturing sector (the ‘Manufacturing Circle’), but also voices within the Economic Development Department and the Department of Trade and Industry, have been increasingly outspoken about the need for a more active regulation of cross-border money-capital flows. More recently, in the context of the 2016 #FeesMustFall protests, students – drawing on the work of Patrick Bond and others – have argued that CC could be instrumental in channelling resources towards education. While the case for CC in South Africa has been increasingly well articulated by those social actors, it has so far failed to convince the National Treasury and the Reserve Bank, which have continued apace with the policies of lifting CC on outflows, and transforming remaining ones into macroprudential regulations.

The present article offers a historical analysis of CC in South Africa with particular reference to the historically and geographically specific social relations of production and material conditions of capital accumulation. The objective is to make sense of the role that CC have historically played in reproducing particular forms of capital accumulation and capitalist class rule in South Africa, but also to shed light on the CC policies currently implemented by the National Treasury and the Reserve Bank.

More generally, the issue of South African CC and how they mediate international money-capital flows is also crucial to understanding broader dynamics of accumulation and dispossession across the African continent, for at least two interrelated reasons.2 First, money-capital flows have been instrumental in what has been termed the ‘new scramble for Africa’, that is, the contemporary practices of primitive accumulation that prey on Africa’s land and natural resources (Moyo, Yeros, and Jha 2012; Shivji 2009). Given the strategic positioning of South Africa as a financial hub for the continent, the implications of South African CC have been much wider than the sole South African economy. Second, the problem of large-scale capital flight, which, as the article will discuss at length, has plagued the South African economy, is not a phenomenon restricted to South Africa. In fact, recent research has shown that it has been an endemic issue for the whole continent, and especially for natural-resource-rich countries (e.g. Ajayi and Ndikumana, 2014). Understanding South Africa’s CC and the class dynamics associated with them has therefore significant implications for understanding the broader political economy of the continent.

The first part of the article briefly reviews the existing literature of CC in South Africa. The main argument is that most of the contributions (owing to their largely descriptive character and/or their empirical focus on measuring the effectiveness of CC) have largely failed to develop an understanding of CC grounded in social relations of production. This is in sharp contrast with a variety of political economy perspectives which have developed analyses of financial policies in South Africa, grounded in the particular form of South African capitalist development and sensitive to class dynamics. The present article is therefore positioned within this latter body of literature. The second part introduces the key components of the theoretical framework to study CC that I have developed elsewhere (Alami 2016). This framework, grounded in materialist state theory and the Marxist theory of money, conceptualises CC as concrete historical political forms through which the capitalist state mediates the contradictory character of global money-capital flows. The third part of the paper then puts the framework to work and provides an analysis of CC in South Africa since the 1930s. The analysis draws upon a range of sources: quantitative data from national accounts, descriptive data on CC from policy documents released by the Reserve Bank, and interviews conducted during a period of extensive fieldwork between September and December 2016.3 My key arguments are the following. First, changing forms of CC have played a key role in facilitating the crisis-led reproduction of essential capitalist social forms, namely the state and money, and have been instrumental in the management of class relations. Second, the concrete forms that CC have taken in South Africa are inseparable from the historical-geographical specificity of accumulation and the uneven unfolding of crises and social class struggles. Third, my analysis shows that by contrast with existing historical accounts of CC in South Africa, working classes have had an active (though indirect) role in shaping CC policies. It is important that those findings inform the design of more progressive forms of CC for South Africa and beyond, that is, CC that aim at transforming social relations and class configurations, and that empower labour vis-à-vis capital. While more policy-oriented research is needed to elaborate the appropriate policy instruments, the conclusion will sketch a series of key objectives that CC would need to meet in order to fulfil this ‘transformative’ role.

The literature on capital controls in South Africa4

It is possible to identify three bodies of literature on CC in South Africa. First, a series of policy documents and statements released by the Reserve Bank provides historical reviews of the CC that were deployed in South Africa (Stals 1998; Farrell and Todani 2004; SARB 2015). Even though some of those contributions locate the deployment of CC within the unfolding of key historical events and within debates between South African policy-makers (Kahn 1991), these papers remain largely descriptive: rather than investigating CC with reference to the material conditions of accumulation, their purpose is to review the different forms of CC that were deployed, as well as to provide in-depth explanations of how these worked. For instance, Gidlow explains how the ‘blocked rand’ functioned (1976). Garner provides an analysis of the ‘financial rand’ mechanism (1994). These papers, however, constitute valuable sources which I exploit in the analysis conducted in the third part of the paper, ‘Capital controls in South Africa since the 1930s’.

A second body of literature consists of publications released in large parts by researchers at the Reserve Bank and the Treasury (or by academics mandated by those institutions) which develop neoclassical economics models and econometric analyses in order to empirically investigate the effectiveness of South African CC at different historical junctures. For instance, Farrell looks at the impact of CC in reducing the volatility of the exchange rate (2001). Havemann looks at the impact of CC on policy-making in light of the ‘macroeconomic trilemma’ (monetary independence, exchange rate stability and capital-account openness) (2014). This literature also pays particular intention to the longer-term ‘economic distortions’ and/or ‘unintended consequences’ associated with CC (Havemann 2014; Schaling 2005).

A third body of literature is mainly concerned with the impact of capital-account liberalisation (i.e. the lifting of CC) in the 1990s–2000s on the South African economy. While mainstream approaches have debated the impact in terms of economic growth (Tswamuno, Pardee, and Wunnava 2007; Khumalo and Kapingura 2014), heterodox perspectives have been largely critical of capital-account liberalisation. The latter group of scholars argue that capital-account liberalisation has had a poor impact in terms of growth, has contributed to unsustainable patterns of financialisation, has rendered the economy extremely dependent on money-capital inflows, and has generated deep financial fragilities and vulnerabilities (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011a; Mohamed 2012; McKenzie and Pons-Vignon 2012; Bond 2013). Accordingly, an important political conclusion of that literature is that the process of capital-account liberalisation should come to a halt, and new forms of CC on inflows should be implemented. These contributions are doubly important: they have both challenged the rationale for capital-account liberalisation on theoretical grounds, and sought to explain capital-account liberalisation policies by examining the configuration of social forces in South Africa (Habib and Padayachee 2000; Isaacs 2014; Ansari 2017). The present article is positioned as a contribution to this line of research. In particular, it follows a similar approach to that developed by Ashman and Fine: it provides a historical analysis of financial policies and dynamics in light of the historically and geographically specific form of accumulation and the associated configuration of social relations and struggles in South Africa (Ashman and Fine 2013). The next section outlines the theoretical framework deployed in the analysis.

A theoretical framework to study capital controls from a class perspective

Capital controls are commonly defined as regulations that restrict cross-border private capital flows, registered in the capital account of the balance of payments (IMF 2012). Exchange controls are measures that restrict the external convertibility of the currency as well as trade-related flows of money (flows registered in the current account). In the rest of this article, the term CC will be used to designate both types of measures. While those ‘accounting’ types of definition are useful for descriptive purposes, I argue that they are poorly suitable for analytical purposes. This is because these definitions don’t say much about what states actually do (or aim to do) when they deploy CC. This is problematic since, as mentioned in the introduction, historical case studies (Chile, Malaysia, Brazil) have shown that those regulations have played a particular role in reproducing class-based strategies and in sustaining particular forms of capital accumulation. What is needed, then, is a framework that allows the examination of CC within the broader role of the capitalist state in the antagonistic and crisis-ridden process of capital valorisation, and with specific reference to the historically and geographically specific dynamics of capital accumulation prevailing in the country studied. I argue that such a framework can be developed by drawing upon materialist state theory and the Marxist theory of money (Alami 2016). This framework, which insists upon the social constitution and the class character of the state and money-capital flows, can be briefly summarised as follows.

Given that the state is a historically specific political form assumed by antagonistic class relations (Clarke 1991; Bonefeld 1992), my contention is that CC should be conceptualised as (national) political mediations of global money-capital flows. This mediation is inherently unstable and contradictory. This is because, from the perspective of the capitalist state, there is a contradiction immanent in the form of money-capital: money-capital constitutes a source of social wealth that can be distributed to various social subjects through diverse state policies for the purpose of fostering accumulation and managing class relations, but the movement of money-capital also shapes the modalities through which the state politically contains and integrates labour within its national space of valorisation. Accordingly, CC should be conceptualised as the concrete historical political forms through which the capitalist state mediates the self-contradictory mode of existence of money-capital, that is, money-capital as a source of social wealth that can be distributed to various social subjects, and as the expression of the disciplinary power of capital-in-general.

The following section applies this theoretical framework to the case of South Africa, in light of the historically and geographically specific form of accumulation and the associated configuration of social relations and struggles. This specificity, a vast political economy literature has shown following the seminal work of Fine and Rustomjee (1996), is that capital accumulation since the discovery of gold and diamonds in the 1860s has been driven by the Minerals–Energy Complex (MEC). The MEC is not only a set of sectors with particularly strong backward and forward linkages, it is also a ‘system of accumulation’. Fine and Rustomjee’s argument is that South African industrial capital accumulation has been continuously dependent on the appropriation of surplus (in the form of ground rent, and mediated by a series of state policies and institutions) generated in the mining and energy sectors. In other words, the essence of South African capitalist development, despite changing concrete historically specific institutional forms, is a particular case of nature-dependent capital accumulation through ground-rent appropriation.5 The following section provides an analysis of CC in South Africa since the 1930s, in light of this historical-geographical specificity, and associated class configurations. The analysis draws upon a range of sources: quantitative data from the national accounts, descriptive data on CC from policy documents released by the Reserve Bank, and interviews conducted during a period of extensive fieldwork between September and December 2016.

Capital controls in South Africa since the 1930s

Capital controls in the 1930s

The Great Depression, followed by Britain’s abandonment of the gold standard in 1931, triggered massive capital outflows from South Africa. Despite the fact that South Africa weathered the crisis relatively well, owing to large flows of ground rent generated in the gold-mining sector, ‘investors were shifting enormous amounts of money out of South Africa (£20 million in 1932)’ (Bond 2003, 264–265). This put pressure on the gold standard in South Africa, leading to its abandonment in 1932 by the Hertzog administration in order to avoid deflationary adjustment. Indeed, a brutal deflationary adjustment ‘would have compromised the civilised labour policy’, which was instrumental for the management of class relations by the Hertzog government: it made important concessions to the ‘poor white workers, (“civilised workers” by opposition with Black proletarians) … to avoid their radicalisation’ (Davies et al. 1976, 11–12). In that context, a legislative framework for CC was developed. In 1933, the Currency and Exchange Act established a framework for foreign exchange intervention by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) in order to ‘prevent undue fluctuations’ of the South African pound ‘in relation to the units of currency which are legal tender in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’.6 It also allowed the SARB to deploy CC ‘in regard to any matter directly or indirectly relating to or affecting or having any bearing upon currency, banking or exchanges’ (Union Gazette 1933, lxviii–lxx). In 1939, CC were implemented to restrict outflows to non-Sterling Area countries, and ensure the free movement of funds, emanating mainly from the United Kingdom, within the Sterling Area (Stals 1998).

Capital controls and the development of import-substituting industrialisation (1940s–late 1960s)

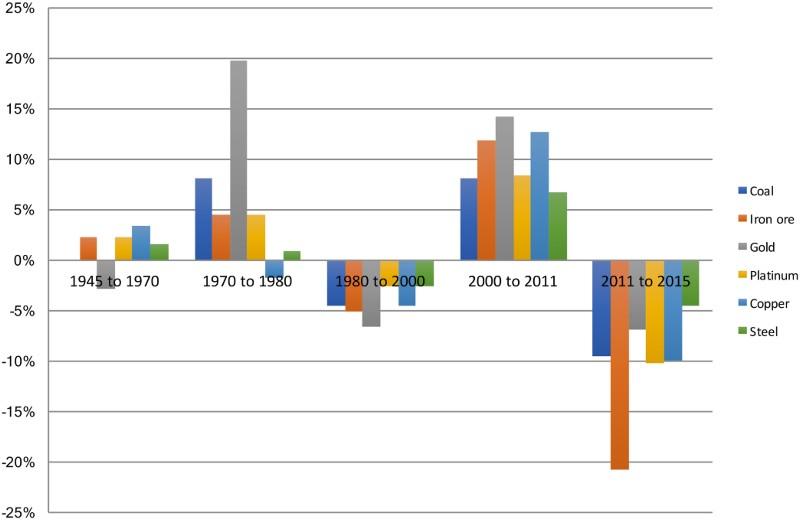

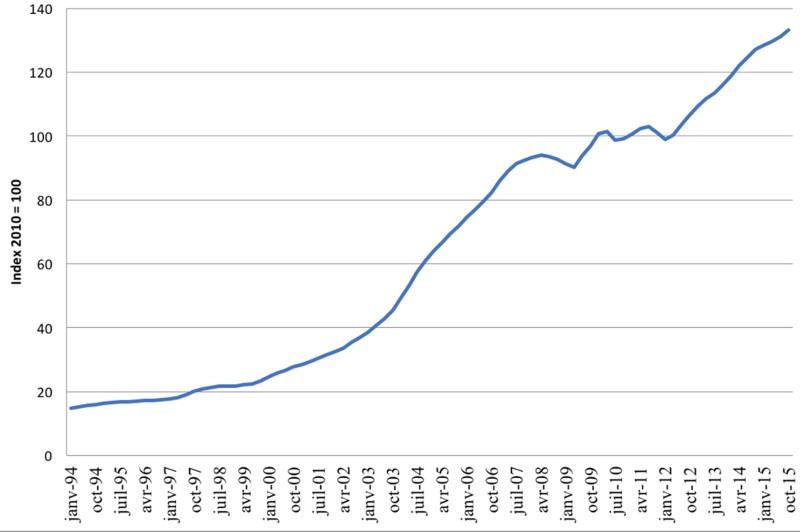

The post-war period saw the acceleration of accumulation through import-substituting industrialisation (ISI), characterised by some significant levels of industrial capital accumulation, higher capital intensity in mining and agriculture, and relatively high growth rates (Fine and Rustomjee 1996). The material basis for this boom was provided by large flows of ground rent (resulting from the discovery of new gold fields in the Orange Free State during the 1940s and from the boom in primary commodity markets associated with the Korean War, as shown in Figure 1) as well as by large money-capital inflows.

Average annual change in prices of a series of key mining commodities, 1945–2015. Source: own elaboration based on data in Jacks 2013, suggested by Neva Makgetla, personal correspondence.

The Smuts government deployed a series of policies to channel these flows, and the Sterling Area CC were gradually phased out and tailored to proceed with the ISI strategy (Davis et al. 1976, 27). The development of sophisticated financial markets and new financial institutions by the mining houses and by the state (the National Finance Corporation) played a key role in mediating money-capital inflows, largely sourced from British financial institutions. The large flows of external wealth were also important for managing class relations. The National Party, which won power in 1948, favoured the emergence of a class of financial industrial and commercial Afrikaner capitalists, by centralising and channelling ground rent generated in the agricultural sector. It also institutionalised existing racial practices, and officially established the apartheid regime. Rapid financial development, partly owing to large inflows, allowed the financing of the construction of urban areas and townships such as Soweto (Bond 2003).

The reversal of money-capital flows in the late 1950s marked an important step in CC policies: the state deployed a tighter and more pervasive framework to prevent large-scale capital flight (Farrell and Todani 2004) in a context of intensified and brutally repressed African working-class struggles which culminated with the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, and the declaration of a state of emergency by the National Party. When outflows accelerated in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre, leading to a collapse of gold and foreign exchange reserves, CC were further tightened, restricting for the first time ‘the repatriation of non-resident investment funds from the country’ (Stals 1998). The National Party government decided to block the repatriation of the proceeds of sales of South African securities by non-residents (the ‘blocked rand’ mechanism). Those CC, promulgated in Government Notices R1111 and R1112 of 1 December 1961, and issued in terms of the Currency and Exchanges Act 9 of 1933, were at the time considered to be emergency crisis measures, but the act still provides the basis for the existing legislative framework for CC. Importantly, it states that ‘the control over South Africa’s foreign currency reserves, as well as the accruals and spending thereof, is vested in the Treasury’ and that ‘the [SARB] is responsible, on behalf of the Minister of Finance, for the day-to-day administration of exchange controls in South Africa’ (SARB website).

In the 1960s, money-capital inflows recovered, predominantly under the form of direct investment by transnational corporations (TNCs) through the establishment of subsidiaries in South Africa in industries producing for the domestic market and industries processing primary commodities. This process was ‘intimately connected’ to the intensification of racial oppression (Clarke 1978). Indeed, the period saw the extension of apartheid policies and spatial control of the black population through the development of Bantustans, and mass eviction and forced removals under the Group Areas acts, in order to form a disciplined urban labour force. The flow of ground rent also expanded, with rapid growth in both mining and agriculture, and the apartheid state scaled up policies to channel part of it to industrial capitals, including through heavy investment in electricity and transport (Fine and Rustomjee 1996, 160–168). This provided the conditions for the mid 1960s economic boom and significant levels of accumulation, as shown in Figure 2.

Capital controls and import-substitution industrialisation development (1970s–85)

In the early 1970s, the ISI growth model reached its limits. These included: the limited character of industrialisation; the relatively small domestic market for manufactured goods showing growing signs of chronic overproduction; a dependence on gold as a source of foreign exchange. The model was also dependent on relatively cheap black labour, which was increasingly insubordinate. Indeed, the 1970s saw sharp outbursts of African working-class resistance in many forms, including spontaneous strike action in 1973 by workers in the textile and metal industries around Durban, the emergence of the Black Consciousness movement, and the intensification of student and community protests after the 1976 Soweto riots. The situation got worse after the 1972–75 commodity boom came to an end, and the mass of ground rent available for appropriation decreased owing to a sharp decline in gold prices, as shown in Figure 1. As a result, there was a marked decrease in industrial capital accumulation and a decline in growth rates. Moreover, with the flow of ground rent drying up, large-scale capitals, state-owned companies and the state increasingly relied on money-capital inflows in the form of syndicated bank loans and public bond issues on Euromarkets, which became the most important source of funding over the period (Clarke 1978; Padayachee 1988).

This was however interrupted by a brutal episode of capital flight in 1976–77, in the aftermath of the Soweto riots and the military intervention in Angola, plunging the economy into recession. The government adjusted CC in order to mediate this pattern of money-capital flows. In February 1976, it introduced the ‘securities rand’ to further attract inflows and curb the illegal capital flight practices that took place under the ‘blocked rand’ mechanism. The ‘securities rand’ allowed for the conversion of the proceeds of the sale of non-resident owned securities in South Africa into securities rand, tradable between non-residents at a lower exchange rate (Farrell and Todani 2004). The mechanism was tightened in response to the capital flight episode triggered by the Soweto riots, and remained in place until 1979. In the early 1980s, several CC on the capital account were lifted in order to further attract inflows and limit outflows. This included the replacement of the ‘securities rand’ by the ‘financial rand’ (which lasted until 1983). It established a dual exchange-rate system, one for capital-account transactions by non-residents (the financial rand), and one for current-account transactions (the commercial rand). It aimed to conciliate the need to attract inflows, a growing demand for foreign exchange to finance imports of capital goods, and CC on outflows (Stals 1998). In a context of slowing inflows in 1983 (owing to the previously mentioned issues, as well as the unfolding of the Third World debt crisis), the state abolished the financial rand, adopted a floating exchange rate, lifted CC on non-residents and started liberalising the financial and banking sectors.

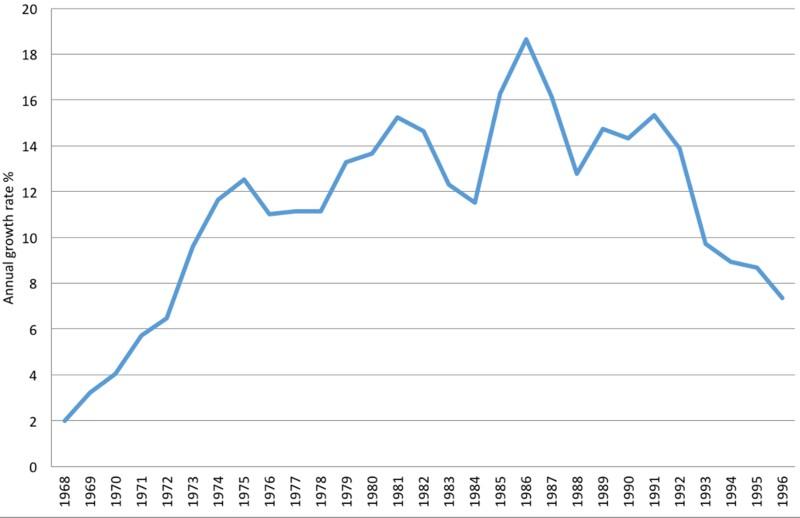

The dependence on inflows further grew in the 1980s, and loans became increasingly short-term, ‘[enabling] a quick retreat [of international banks] in the case of adverse political or economic events in South Africa’ (Padayachee 1988, 367). Foreign-denominated short-term debt built up, and constituted a growing form of financial fragility based upon currency and maturity mismatches. Besides, inflation was growing at double-digit rates (as shown in Figure 3), and government borrowing increased to finance violent police repression and military expenditures.

Inflation growth rates % in South Africa, 1968–96. Source: own elaboration based on World Bank Development Indicators.

The build-up of short-term foreign debt became increasingly problematic as the rand was under constant pressure, in a context of uttermost working-class insubordination: the early 1980s saw nationwide school boycotts, the creation of the United Democratic Front in 1983, a national alliance of community organisations (women, youth, cultural and civic organisations) and trade unions, huge strike activity in 1984, the township uprisings of 1984–85 and the intensification of national liberation movements’ struggles. These were violently repressed, and the Botha government declared a state of emergency in July 1985. At the same time, the international anti-apartheid disinvestment movement increased its pressure on TNCs and international banks. It became clear, including for the international financial community, that the apartheid state had lost the ability to manage class relations. The rand collapsed in 1984–85, increasing the rand value of the foreign debt and major New York and London banks withdrew lines of credit. Massive capital flight forced the government to suspend trading on the foreign exchange and stock markets from 28 August to 1 September 1985. President Botha declared default and a moratorium on foreign debt; CC on outflows were deployed and the financial rand system was reintroduced (Farrell and Todani 2004, 17; Mohamed 2012, 18).

Capital controls during the isolation and democratic transition period (1985–early 1990s)

The debt moratorium, the reintroduction of the financial rand, the temporary suspension of the financial liberalisation policies and intensifying international sanctions inaugurated a period of relative isolation for South Africa. Inflows turned negative between 1986 and 1991, as ‘225 US corporations, and about 20 per cent of UK firms, [departed] between 1984 and 1988’ (Gelb and Black 2004, 178). Ground-rent flows also dried up in the late 1980s–early 1990s, owing to falling primary commodity prices on international markets (as shown in Figure 1), which worsened the capitalist crisis. Inflation and public debt rose as the National Party government extended monetary flows to ‘compensate and protect its supporters in the face of inevitable change’ (Habib and Padayachee 2000, 247). Capital flight put serious pressure on the financial rand in the early 1990s as the large capitals that dominated the economy started a process of restructuring and internationalisation, and shifted portions of their assets abroad, ‘beyond the reach of the future democratic state’ (Rustomjee 1991, 89). Profit and investment rates fell, and a huge portion of surplus was increasingly channelled into the financial system and into speculative construction of commercial property. This contributed to enhanced financial activity, the formation of asset price bubbles and the development of a deep, sophisticated and highly concentrated financial system (Bond 2003; Ashman and Fine 2013).

The crisis also accelerated the move towards a new growth strategy, driven by the implementation of neoliberal reforms. It is worth insisting that this shift did not signal a change in the fundamental nature of capital accumulation in South Africa, which has remained determined by the MEC (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011a). Comprehensive measures were taken in order to restore access to global money-capital, and to take advantage of favourable global liquidity conditions in the early 1990s. There was a turn to monetarism to control inflation, a growing commitment to reduce the fiscal deficit, and a series of measures to liberalise the financial system and open the capital account was undertaken. It is in this context that the negotiations over a new constitution and democratic elections started, after the unbanning of the African National Congress (ANC) and other proscribed liberation organisations in 1990. During this process, the question of ensuring business confidence in order to secure money-capital inflows was central. Scholars have argued that this concern explains the shift towards an accommodative strategy in ANC discussion guidelines on future economic policy, as well as the continuation and deepening of the financial liberalisation and opening policies after the election of the government of National Unity in April 1994 (Rustomjee 1991; Habib and Padayachee 2000). The views that South Africa had to be re-integrated into the global economy in order to restore growth, and that money-capital inflows were necessary to compensate for low levels of domestic savings, became deeply entrenched amongst policy-makers. Those views have endured to this day, as was clear from my interviews with policy-makers at the Treasury and the SARB (Interviews 1, 3, 4).

Money-capital inflows recovered in 1991 and further accelerated after the debt standstill arrangement of 1993, the removal of international punitive actions against the South African economy in 1994, the abolition of the financial rand in March 1995 and the relaxing of a series of CC, as shown in Figure 4. CC on the current account were completely relaxed, CC on the capital account for non-residents were lifted and asset swap arrangements facilitated outflows for resident institutional investors (Farrell and Todani 2004). Strict CC on residents were maintained to avoid large-scale capital flight.

Net capital account and composition of foreign money-capital flows, 1985–2014 (R million). Source: own elaboration based on SARB data.

Importantly, the nature and composition of the inflows changed: they became increasingly driven by short-term portfolio flows. This entailed a change in the form through which money-capital flows disciplined the state, characterised by the movement of highly volatile short-term portfolio flows exercising pressure on the exchange rate.

Capital controls during the 1996–2000 period

The destabilising effects of volatile money-capital flows rapidly manifested themselves. A sudden stop in inflows triggered a brutal depreciation of the rand in early 1996, as shown in Figure 5.

Rand real effective exchange rate, 1994–2014. Source: own elaboration based on Bank of International Settlements data.

In that context Mandela’s government announced an orthodox macroeconomic adjustment plan, the Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) framework. GEAR had devastating effects in terms of deindustrialisation and growing unemployment, which particularly hit key labour-intensive sectors and contributed to disciplining and fragmenting the working class (Bond 2003, 49; Desai 2003). GEAR was nevertheless relatively successful in taming inflation, and was instrumental in attracting large inflows (as described below). Mandela’s government also continued liberalising the capital account by gradually relaxing CC as well as by adopting a laxer attitude towards their enforcement (Mohamed 2012). The scope of the asset swap arrangements was broadened to a larger variety of financial institutions (insurers, pension funds, fund managers) and the limits on foreign investments were increased. CC on short-term trade financing and inter-bank financing arrangements were eased, and administrative procedures were simplified (Stals 1998; SARB 2015). Overall, ‘three-quarters of the [CC] in 1994 had been eliminated by 1998’ (Gelb and Black 2004, 179). Moreover, the 1996 Constitution granted the SARB full independence, and set out that its primary goal was protecting the value of the currency. It maintained high interest rates over the period, as shown in Figure 6.

Discount rate of the SARB, 1994–2013, monthly observations. Source: own elaboration based on data from the IMF.

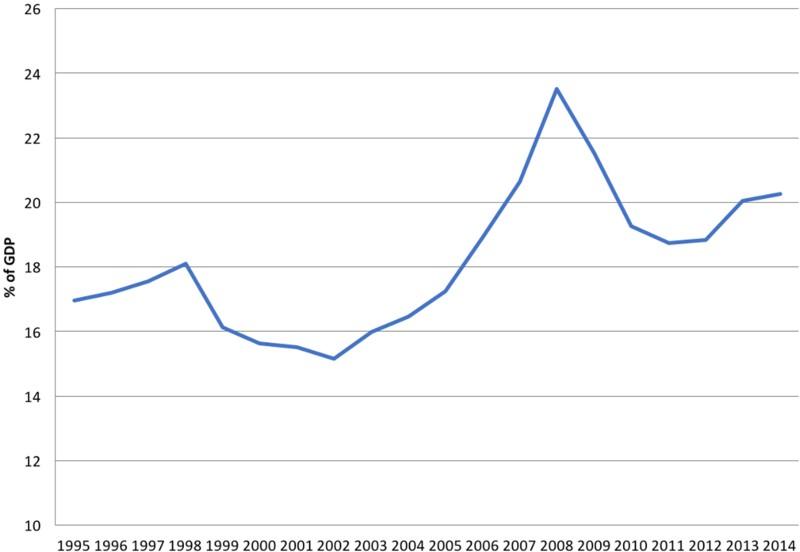

Besides, the SARB ran a growing ‘oversold forward book’, a policy instrument that aimed at insuring industrial and banking capitals against the risk of currency devaluation. Importantly, and despite the fact that social spending was subordinated to fiscal discipline and inflation control, these financial liberalisation measures were framed by the state as policies designed ‘to address the inequality, poverty and unemployment legacy of apartheid’ (Mohamed 2012, 35). In conjunction with the ANC government’s programme of affirmative action, Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), they would also help create a new progressive black capitalist class. These policies were clearly successful in attracting large volumes of inflows. Nevertheless, inflows did not contribute much to industrial capital accumulation. Foreign direct investment remained very low in comparison with other emerging capitalist countries. Money-capital inflows mainly financed consumption and booms in asset price bubbles. While rates of gross fixed capital formation remained at very low levels (see Figure 7), there was a boom in fictitious capital accumulation on the stock market (Figure 8).

Gross fixed capital formation as % of GDP in South Africa, 1995–2014. Source: own elaboration based on World Bank Development Indicators.

Accumulation of the three ‘elementary forms’ of fictitious capital in South Africa. Source: own elaboration based on World Bank Development Indicators.

This contributed to the creation of a black bourgeoisie (that the BEE strategy aimed to develop) whose wealth was increasingly derived from ownership of financial assets. By early 2000, 9% of the stock market was black-controlled (Bond 2003). In terms of the management of the balance of payments, South Africa became increasingly dependent on money-capital inflows to fund structural current account deficits, as shown in Figure 9.

Evolution of the current and capital accounts in South Africa, 1985–2015. Source: own elaboration based on SARB data.

Sustained illicit capital flight continued over the period. Mohamed and Finnoff estimate that it rose to an average of 9.2% of GDP per year, which was higher than during the politically unstable period of the 1980s (2004, 12–15). They argue that this ‘[indicated] a multi-year effort to build up wealth reserves outside of South Africa’ and reflected the deep lack of trust of the (mostly white) capitalist class in the (black) ANC government’s ability to foster accumulation and control the poor.

This race dimension7 was also evident during the late 1998 brutal capital-account reversal, following the Asian crisis. Outflows accelerated when the government announced the nomination of a new SARB governor, Tito Mboweni, the first black South African to hold the position. Many in the investor and business community doubted that Mboweni would be capable of continuing the tough anti-inflation stance of his (white) predecessor Chris Stals (Handley 2005). This put intense pressure on the exchange rate, and the SARB massively intervened by running up the oversold forward book to prevent a currency crash. The intervention was costly (it took more than five years to pay down the net open forward position) and largely unsuccessful, and it is a key factor in explaining the largely ‘hands-off’ approach of the SARB in terms of currency intervention since then. As several interviewees put it (all using the same expression), the SARB ‘got its fingers burnt’. This was a defining experience in terms of what South African policy-makers in the Treasury and the SARB think that they can (and cannot) do to ‘lean against the wind’ (Interviews 1, 3, 4, 6, 10). The SARB publicly announced its commitment to a floating exchange rate.

A series of measures was then undertaken to restore access to global money-capital flows, including tax cuts, tighter fiscal discipline and high interest rates. An important measure concerning the capital account was also implemented in order to facilitate the restructuring and financialisation of South African large capitals (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011b). Between 1998 and 2001, several conglomerates were allowed to shift their primary stock market listings abroad, mainly to London and Sydney. The rationale behind that decision was that the conglomerates did not have room to expand in the South African domestic market, needed to internationalise to become more competitive, would raise finance at a lower cost and reduce their financial and currency risk exposure, and would in return raise levels of investment in South Africa (Interview 8). Yet, the capitals that listed abroad have not recorded higher levels of investment in South Africa (Chabane, Roberts, and Goldstein 2006). While the extent to which the other objectives were achieved is difficult to assess, what is also sure is that this has triggered a sustained outflow of profits and dividends, creating a structural deficit in the income account. Figure 10 shows how the structural deficit in the net income account has contributed to the worsening current account deficit in the 2000s.

Capital controls during the crisis period 2000–03

While money-capital inflows recovered in late 1999, they remained very volatile. They rapidly declined again in 2001, in a context of global liquidity contraction following the collapse of the dotcom bubble, political turmoil in neighbouring Zimbabwe and heightened currency speculation against the rand, triggering another currency crash as shown in Figure 5. In that context, CC and fiscal discipline were tightened, interest rates were raised (Figure 6) and the SARB adopted an inflation-targeting framework with a commitment to maintain inflation between a 3 to 6% target range (Figure 11). Inflation-targeting was justified by the rhetoric of macroeconomic stability, and prioritised the imperatives of maintaining low inflation and attracting money-capital inflows (Isaacs 2014).

The period also saw a three-pronged landmark shift in the management of the capital account. First, the Treasury and the SARB began transforming remaining CC into ‘macroprudential measures’ for banks and institutional funds. Leape and Thomas explain:

The principal objective of [CC] was to limit outflows of capital. Prudential regulation is instead concerned with the financial soundness of individual institutions and the broader objective of systemic stability, as part of the overall framework for supporting macroeconomic stability. (Leape and Thomas 2011, iii)

As Figure 5 shows, the rand recovered extremely quickly in 2002. The Mbeki administration further relaxed some CC, both for private individuals and for capitals. It also introduced a foreign exchange and tax ‘amnesty’, the objective of which was to regularise assets held abroad and undisclosed offshore investments, and to include them in the tax base. It was, however, quite an explicit recognition by the government that it would rather try and regularise the assets illicitly held abroad than tackle the issue of sustained capital flight (Bond 2003; Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011b).

Capital controls during the 2004–08 period

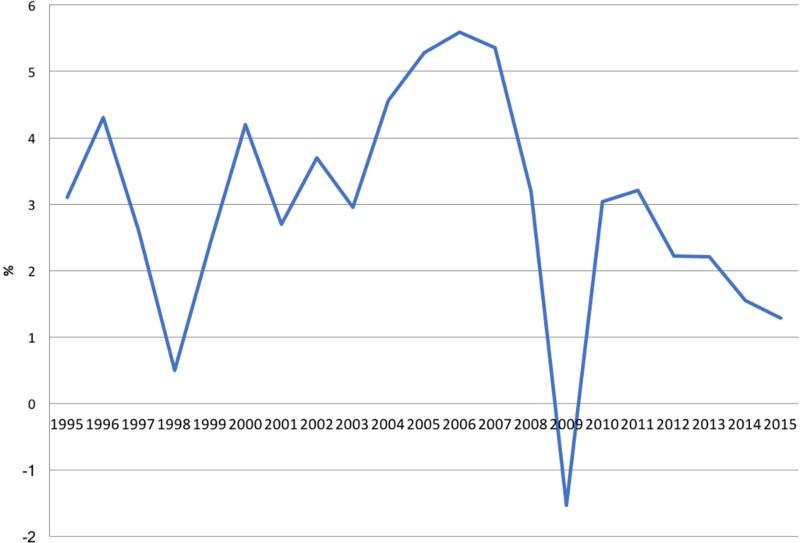

Over this period, characterised by abundant liquidity in international markets and a boom in global primary commodity prices (as shown in Figure 1), South Africa received large volumes of ground-rent and money-capital flows. Large money-capital inflows were attracted by the commodity super-cycle, a strong currency and relatively high interest rates. While those flows, alongside ground-rent flows, contributed to relatively high economic growth rates (as shown in Figure 12) in comparison with previous (and subsequent) years, the impact in terms of productive accumulation was disappointing (Figure 7).

Annual GDP growth rates in South Africa, 1995–2015. Source: own elaboration based on data from the World Bank World Development Indicators.

The acute volatility of the rand significantly deterred investment, and the sustained currency appreciation between 2003 and 2007 considerably hurt the external competitiveness of the manufacturing sector. Besides, the sectoral allocation of money-capital inflows limited economic diversification. Inflows reinforced the dominance of the MEC over the economy, though in an increasingly globalised and financialised form, and fuelled unprecedented stock market capitalisation as well as growth in the financial and service sectors linked to debt-driven consumption (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011a; Mohamed 2012). Inflows also fuelled a residential property price bubble and associated residential mortgage bonds. Figure 13 shows the impressive rise in residential property prices over the period.

Monthly residential property prices in South Africa, 1994–2015. Source: own elaboration based on data from the Bank of International Settlements.

Capital flight also continued to be a major issue for the South African economy, with short-term money-capital inflows financing long-term capital outflows. Such outflows, supported by an overvalued currency, averaged 12% of GDP between 2001 and 2006 and peaked at 23.4% in 2007 (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011b). They largely benefited a small minority who were the beneficiaries of conglomerate ownership and control. In sum, the boom in money-capital inflows contributed poorly to productive accumulation, but fuelled massive accumulation of different forms of fictitious capital (Figure 8) and financed a structural current-account deficit as well as sustained capital flight. However, the way money-capital inflows were absorbed by the economy and/or channelled by the state was instrumental in the management of class relations. First, money-capital flows, by maintaining high equity and real-estate prices, favoured exacerbated elite consumption. Indeed, the largest property increases were in the prices of luxury houses in established suburbs, thereby benefiting (mostly white) rich homeowners (Bond 2013). But price increases also concerned middle-income properties of the middle class (McKenzie and Pons-Vignon 2012). By maintaining high asset prices, money-capital inflows were also instrumental in the second phase of the BEE, which started in the early 2000s, and largely relied on financial market operations and mergers and acquisitions (Chabane, Roberts, and Goldstein 2006; Ashman and Fine 2013). Second, money-capital inflows (and lower interest rates until mid 2006) fuelled rapid credit extension to the private non-financial sector, most of it directed to the household sector. This process was importantly facilitated by the state, which adapted the regulatory framework to extend credit relations to the poor and to support the BEE policy. Key regulations in that regard have been the 2003 Financial Sector Charter and the 2005 National Credit Act, which aimed specifically at extending credit to the poor, the rural population and other marginalised groups. The priority of the Act was much more to rapidly expand credit markets than to protect consumers (Schraten 2014). Rapidly growing consumer debt was crucial to sustain increasing household consumption expenditures. Household debt as a percentage of disposable income jumped from 50% in 2005 to 80% in 2008 (Bond 2014, 181).

Money-capital inflows were also directly channelled by and through the state. They helped finance a slightly expanded social wage, based on the expansion of the social grants programme, including unconditional cash transfers to poor households with children, disabled people and pensioners (Interviews 8, 9; Bond 2014). Inflows were also channelled into large-scale infrastructure development. These investments were responsible for the significant increase in rates of accumulation in 2005–08, as shown in Figure 7. As the ANC government channelled large money-capital inflows, it increasingly presented itself as a developmental state. Indeed, after 2004 the developmental state rhetoric became omnipresent in ANC and government documents (Netshitenzhe 2011). Large inflows were therefore instrumental in the ideological representation of the ANC government as a pro-poor developmental state.

In order to sustain money-capital inflows, the ANC government maintained a conservative macroeconomic policy framework, characterised by relative fiscal discipline and high interest rates. The strongly appreciating currency (Figure 5) served as an anchor to control inflation (Interviews 1, 4, 6). The ANC government also took advantage of the boom in inflows to increase markedly the pace of reserve accumulation, as shown in Figure 14.

Total gold and other foreign exchange reserves of the SARB, 2000–14 (R millions). Source: own elaboration based on SARB data.

Between 2005 and 2008, it continued to lift some CC, and transformed some of the remaining ones into a system of reporting and monitoring of foreign exposures of institutional investors, moving forward with the strategy of establishing an institutional framework for a risk-based approach to financial regulation started in the early 2000s (Leape and Thomas 2011, ii; Interviews 3, 4, 10). The foreign exposure limit on collective investment scheme management companies and for investment managers was raised to 30% of total retail assets, with an additional 5% for portfolio investment in Africa (SARB 2015).

Capital controls during the post-crisis period

The boom in inflows, mediated by changing forms of CC, has made South Africa considerably more vulnerable to volatile short-term money-capital flows, with far-reaching consequences for financial instability and fragility (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011a; Mohamed 2012, 44). These became increasingly visible in 2006–08, in the context of drastic currency depreciations (see Figure 5), triggered by a combination of factors: a sharp slide in gold prices, the official announcement of a record current-account deficit of 7%, worrying household debt to income ratios, signals that the US Federal Reserve System and the Bank of Japan were going to end lax monetary policies, changes in the ANC’s leadership in December 2007, large-scale xenophobic violence in May 2008 and the ‘recall’ of Mbeki in September 2008, followed by the eruption of the global financial crisis (Dorsch 2006). Still, CC policies in the post-crisis period were characterised by continuity and deepening (Interviews 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). A series of CC was lifted between 2009 and 2011 in order to benefit from the global money-capital flow ‘bonanza’ of the quantitative-easing era, and continue the channelling of money-capital flows following the modalities previously described (Interviews 8, 9). Measures mainly consisted in reducing ‘red tape’ regulations on capitals and private individuals for outward investments as well as significantly increasing the investment allowance abroad (with an additional allowance for investment towards the African continent, consolidating and deepening the continental financial hub strategy). The shift towards macroprudential regulations for institutional investors was also continued, and accompanied with the authorisation for resident capitals, trusts, partnerships and banks to participate without restriction in the rand futures of the stock exchange in order to manage their foreign exposure (SARB 2015). In July 2010, a second tax and foreign exchange amnesty programme was introduced (the Voluntary Disclosure Programme), as part of the move to continue capital-account liberalisation (Ashman, Fine, and Newman 2011b). The Treasury also extended funding assistance to the SARB in order to slightly accelerate the policy of sterilised reserve accumulation (see Figure 14).

South Africa attracted large but highly volatile inflows, driven by bond flows (associated with carry trade operations9), as shown in Figure 4. Their acute volatility was due to external events (such as the Federal Reserve ‘taper tantrum’10 and the worsening of the Eurozone crisis in mid 2011) but also to social and political unrest in South Africa. This included the so-called service delivery protests (owing to poor municipal services and lack of housing for the poor), a massive (and successful) public sector strike in 2009, demonstrations against the 2010 World Cup, and shack dwellers’ social movements in urban peripheries such as Abahlali baseMjondolo in Durban struggling for socio-economic and spatial justice in urban areas (Pithouse 2009; Hart 2013). Money-capital inflows further slowed down from 2012 onwards, as the global commodity boom came to an end, with, in a context of growing tensions within the ruling Tripartite Alliance (the ANC, the South African Communist Party [SACP] and COSATU), corruption scandals within government, the growing perception by capital that the BEE policy constitutes an obstacle to accumulation, and widespread labour insubordination in the platinum-mining sector. This included the Marikana massacre, where 34 striking miners were shot dead by the police, and the large-scale wildcat strikes that followed (Bond 2014). In an attempt to sustain inflows, tighter monetary and fiscal policies were implemented, as well as a new set of measures to relax and simplify CC, for both large capitals and private individuals between 2012 and 2014.

Conclusion

The article provided an analysis of CC in South Africa since the 1930s, considering the historical-geographical specificity of capital accumulation. The high degree of dependence on the world market (and in particular ground-rent and money-capital flows) has made accumulation weak and vulnerable. This dependence has historically manifested itself as repeated crises under various forms (sovereign, financial and monetary crises), with enormous influence on the modalities through which the South African state has politically contained and integrated labour. Different forms of CC have been deployed and adjusted both to attract money-capital flows (depending on their availability on the world market), and to facilitate the crisis-led reproduction of money and the state (for instance, by occasionally curtailing large-scale capital flight). Put differently, CC have been the concrete historical forms through which the South African state has mediated the self-contradictory mode of existence of money-capital, that is, money-capital as a source of social wealth that can be distributed to various social subjects, and as the expression of the disciplinary power of capital-in-general. This contradiction, immanent in the form of money-capital, cannot be solved. It can only be mediated in different ways by various concrete historical political forms. The following quote by Mandela (from a 1992 speech) is an excellent recognition of this contradiction, and how it is experienced by policy-makers as a trade-off: ‘In order to attract foreign investment we will abide by all internationally recognised standards that are consistent with our objectives of growth with equity’ (emphasis added).

By contrast with capitalist elites’ usual framing of the CC debate in highly technical terms, the class analysis has highlighted the active (though indirect) role of the working classes in shaping CC policies. This has primarily taken two forms in South Africa: (1) events of the class struggle triggered acute episodes of capital flight, forcing the state to design and implement CC to prevent the large-scale outflow of resources, help manage the balance of payments and facilitate the regulation of money and the public debt; (2) the working classes also had an indirect influence on the design of CC, through the various state attempts at controlling and integrating them. Accordingly, the article has shown that there has been nothing inherently progressive about South African CC. In fact, CC have been instrumental in facilitating the crisis-led reproduction of essential capitalist social forms, namely the state and money. Consequently, the challenge for the Left and the working classes in South Africa and elsewhere is to move to a more direct role in shaping CC policies, and to push for ‘transformative’ forms of CC, i.e. CC that aim at transforming social relations and class configurations, and that empower labour vis-à-vis capital (Epstein 2012; Dierckx 2015). While more policy-oriented research is needed to design the appropriate arsenal of policy instruments that would fit that purpose in South Africa, my argument is that it is possible, based on the above analysis, to identify a series of key (interrelated) objectives that the CC would need to meet. First, CC should aim at changing the modalities through which the disciplines and vagaries of the global economy are transmitted to South Africa, in order to limit the extent to which the state can use this objective external constraint to shift the burden of deflationary adjustment onto the working class, through contractionary fiscal and monetary policy. This would include measures that aim at curbing the speculative determination of the exchange rate, and in particular the impact of arbitrage and carry trade operations (CC on both portfolio inflows and outflows and on external bank loans, tight limits on financial actors’ foreign exchange exposure, and regulations on foreign exchange derivatives transactions), but also measures that aim at reducing the reach and depth of money-capital in South Africa (measures to limit foreign ownership of financial assets, tighter financial and macroprudential regulations, and controls on credit extension), in order to tame the impact of brutal capital-account reversals. This combination of measures would provide more leverage for labour to struggle over the form of macroeconomic policy.

Second, a key objective would be to transform the mode of external integration into the world economy. As previously shown, the high degree of dependence on short-term money-capital inflows, which forces the state to make South Africa an attractive platform for the valorisation of fictitious capital, has been engineered and maintained by a series of state policies, including CC. Transformative CC would aim at reducing this degree of dependence, by preventing the sustained and long-term outflow of resources (through profit repatriation, interest payments and illicit capital flight), and by changing the structure of the balance of payments. CC, combined with active sterilised foreign exchange intervention (financed by taxes on financial transactions and other forms of progressive taxation), would be instrumental in maintaining a more competitive and less volatile exchange rate for the purpose of improving the trade balance.

Finally, the current configuration of the macroprudential regime (and the special outward allowance to other African countries) has been geared towards absorbing large-scale inflows and facilitating the financialisation and internationalisation of the MEC and its predatory expansion on the African continent. While those regulations should not be jettisoned, since they have proved useful in maintaining a certain level of financial stability and in absorbing external financial shocks, they should be transformed into a regime characterised by continent solidarity, to create some degree of regional isolation against the volatile movement of global money-capital and harness regional resources for pro-labour development.