Introduction

Despite changes towards democracy and improvement in the lives of poor South Africans in the last two decades, the harsh reality is that rural communal areas remain dumping grounds of the poorest, requiring multiple livelihood strategies and social adaptations. The former Gazankulu Bantustan in the Limpopo Province still reflects the basic elements of apartheid times: traditional leadership controlling tribal land, a proletariat dependent on migrant wages and social grants amidst high levels of unemployment, and a substantial difference between the quantity and quality of infrastructure and services in comparison to urban middle-class areas. One important change impacting on South African communal areas in recent decades has been the decline in employment in the mining, manufacturing and agricultural sectors. In 1986 employment in the mines was still at a peak, at 534,000 mine workers, while in 1998 this figure had dropped to only 255,000 owing to the fall in profitability. Structural changes in mining led to social disruption in former labour-producing areas (Harington, McGlashan, and Chelkowska 2004).

What often remained out of sight in many political economic studies were the localised details of the social processes associated with widespread forms of economic exploitation and political domination. Patrick Harries (1994) has documented the deep historical involvement of migrant labourers from Mozambique and the Lowveld in the Kimberley and Witwatersrand mines and has shown how this circulation of labour affected socio-economic life and consciousness. The work of James Ferguson about urban/rural life in Zambia also points to a holistic approach in understanding changing economic patterns by tracing ‘some of its effects on people’s modes of conduct and ways of understanding their lives’ through investigating cultural forms and meanings, patterns of social interaction and identity processes (1999, 11, 12).

A recent article by Isak Niehaus (2012) is a good example of how changes in the political economy can be studied ethnographically. He points out how the shift in post-apartheid times away from witch-hunts towards ‘thief-hunts’ in the South African Lowveld corresponds to changes in gendered and generational distinctions. Whereas older men and women were targeted in the early 1990s as witches, more recently collective action against destructive social forces indexes the shift of power away from the youth. The work of Boet Kotzé (1992), At Fischer (1992) and the author (van der Waal 1991, 1996, 2004) in the former Gazankulu was similarly directed at the experiential level in specific settlements. Historical comparative work, based on detailed ethnographic understanding, is core to this more socially oriented engagement with economic relations.

My aim in this article is to investigate the experience of a changing political economic context by the rural poor in a communal area of the Lowveld and their subsequent individual and collective responses from 1986 to 2013. My point of departure is my research site for 27 years: the Berlyn settlement, situated 12 kilometres south of Letsitele, in a tribal ward of the Nkuna traditional community, and part of the Tzaneen Municipality in the Limpopo Province. It was selected for ethnographic research because of its complex nature, positioned as a rural (then Gazankulu) settlement, situated on the border of a white commercial farming area and close to an industrial growth point, Nkowankowa.

The work of Elizabeth Francis (2000) and others working on chronic poverty, framed with the notion of ‘multiple livelihoods’, provides a productive analytical lens with which the differentiation among individual households and persons, and the variety of economic and social strategies, become evident. The notion of multiple livelihoods can be most productive for understanding changes in the nexus of political economic relations, if these changes are investigated in terms of their social implications. Multiple livelihoods here refers to the many dynamic forms of production and distribution that people rely on in various combinations to meet material and social needs. As Deborah Bryceson (2002) and James Ferguson (2015) point out, the configurations of livelihoods and survival strategies occur in a context of de-agrarianisation and a decrease in the demand for unskilled labour. I argue that changes in the mix of livelihoods in the Lowveld area discussed here are brought about by national and international processes, e.g. in the mining sector and in the developmental state, that impact locally on access to resources, employment opportunities and education. The effect of these changes and the strategic responses they evoke on the village level have very specific gendered and generational dimensions, exemplified by the increasing marginalisation and criminalisation of young men. I will first present an historical overview against which the recent dynamics in this specific research site have to be seen. This will be followed by a focus on changes in the role of land, labour and reproduction that will illustrate the multiple livelihoods that people in the communal areas in the Lowveld and beyond increasingly had to resort to. Lastly, I turn to an analysis of the associated changes in social and governance relations.

From refugees to farm workers and tribal subjects

Although much of the Lowveld was already subdivided into farms for white occupation from 1850 onwards, the family histories of the black residents in the Berlyn settlement point to a long and relatively undisturbed occupation of the alluvial land on both sides of the Letaba River before the Lowveld was effectively, though slowly, occupied by white resident land-owners from the 1920s onwards. Refugees from Mozambique had fled into the Lowveld from the devastations of war and famine between 1840 and 1890. Before the development of commercial farms, black occupants paid rent to mining companies and other landowners. By the early 1900s many families were selling surplus maize to local traders while young men were regularly walking to the mines at Kimberley and the Witwatersrand to obtain cash. From the 1920s white commercial farmers developed irrigated citrus plantations and vegetable fields along the Letaba River, including on the Berlyn farm. Driven by the needs of white commercial farmers and supported by legislation, a major change in relations of production occurred in the following decades: rent tenancy changed into labour tenancy, thereby forcing many black farm-dwellers off the farms into the native reserves, even before the homeland policy was effected from the 1950s onwards.

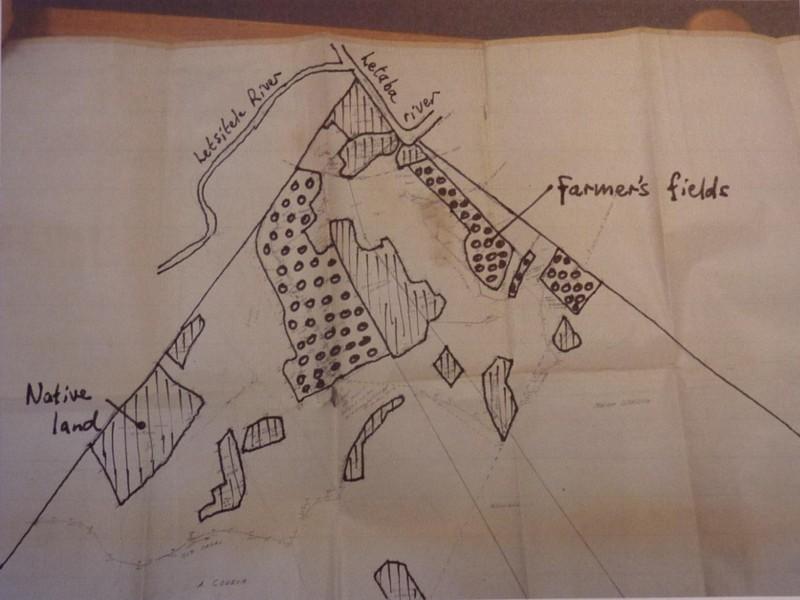

There was a perception among older people in Berlyn during my fieldwork that in the 1940s and 1950s men from Berlyn had been relatively well-off as labour tenants on a white owner’s farm, grazing many cattle and producing food on their fields. They were often able to marry more than one wife from their earnings in the mines and industries. A map of Berlyn farm, drawn in about 1957 (Figure 1), shows 14 ‘native lands’ with an average size of about 14 morgen (12 hectares) spread across the farm, including the very fertile soil next to the Letaba River. The white owner’s citrus plantations and vegetable fields were somewhat smaller than the combined fields of the black residents. The farm inventory, drawn up for the eventual sale of the farm to the South African Native Trust, mentioned one important difference between these two types of fields: the owner used irrigation piping, indicating the more intensive nature of white commercial farming. The family histories tell about a pattern of increasing migrancy in the twentieth century as taxes for government and chief, rent for the land-owner and the need for manufactured goods escalated. Eventually, food had to be bought as commercial farming displaced black subsistence farming. Oral accounts tell about several occasions on which families were removed from prime sites near the Letaba River when the owner extended his fields from the 1950s. Their opportunities for farming and access to water were much reduced in the hilly area on the farm in which they were resettled. Other commercial farms in the Letaba Valley provided job opportunities to some of the uprooted families. Another source of paid work was at the businesses and mines that developed in the area, e.g. the Gravelotte mines from 1934 onwards (Cartwright 1974, 94, 96, 160). A few families moved into the adjoining native reserve (Muhlaba Location) in order to have a more permanent homestead base at less cost in rent or labour.

Highlighted areas indicate the fields of the white owner and black tenants on Berlyn farm, superimposed on a map in the National Archive of South Africa (detail of Berlyn map 1957).

With only a low level of education or no education at all, rural migrants could only find unskilled work. Large households were better able to diversify economically, with some men looking after the local interests of the homestead and its cattle while others spent a year at work before returning for a visit over Easter or Christmas. The effect of labour migration on family life had gender and generational dimensions. Women had to take on more responsibilities at home while their economic contribution in kind was less valued in the money economy, and marriage relationships became stressed. Younger men became more independent of their parents once they started on a migrant career.

In the 1950s a radical re-imagination of the political and economic future became official state policy. In 1951 the Bantu Authorities Act was introduced to recognise traditional leaders as paid political pawns of the government. The governance functions of traditional leaders were strengthened: chiefs were given more powers to collect taxes, control land and adjudicate disputes, and they were made responsible for local development projects (Niehaus, Mohlala, and Shokane 2001, 30). The Nkuna Tribal Authority was formally established for the Muhlaba Location in 19571 and also given jurisdiction over subjects who had been living outside the reserve, including those on Berlyn farm. In order to take segregation to its logical end, apartheid focused on the creation of independent black states. Each of the 10 ‘ethnic groups’ was to have its own ‘homeland’, with Gazankulu emerging as the Bantustan for Tsonga-speakers. ‘Homeland consolidation’ together with agricultural and industrial development was to form the economic base of this large-scale social engineering project that was based on the ideology of racial separation. Berlyn farm was part of the ‘released areas’ earmarked for incorporation into land allocated to black people by the Native Trust and Land Act of 1936. In 1957 the farm was bought by the South African Native Trust, a government body that owned land on behalf of black people, and incorporated into the Nkuna Tribal Authority’s territory.

For the people on Berlyn farm, incorporation into the Nkuna Tribal Authority was followed by the devastation of apartheid-style ‘development’. In the 1960s the government focused increasingly on the development of the ‘homelands’ in an attempt to justify the large-scale relocation of black people. The introduction of large citrus, sisal and mango plantations on Berlyn was part of an agricultural project to generate income for the homeland administration. This project was meant to provide jobs to a number of farm residents, but the scattered homesteads were once more in the way of commercial agricultural expansion. The most important historical event the older people of Berlyn refer to is the forced removal from their homesteads by ‘GG’ (Government Garage) lorries in 1963 in order to make room for this project. In the summer of 1963 the (about 60) families were moved to the hills in the far southern corner of the farm where residential stands had been marked out by agricultural officers. Water provision was insufficient and the first months were marked by suffering as it took time to build shelter and meet basic needs in the absence of any compensation. Many opted to relocate to other parts of the Nkuna Tribal Authority as they did not like the resettlement area.

There are embedded meanings in the colloquial name for the new site: ‘Tickeyline’. It is a reference to the fact that people were forced to live close to one another in the straight lines formed by residential stands. The name also refers to the fact that livelihoods depended more and more on new relations of production: lost was the easy access to communal resources (fertile land, ample grazing and water), available under conditions of rent and labour tenancy. A mix of livelihoods (migrant labour and subsistence farming) that had provided some economic independence had finally been killed off. A tickey, three pennies, a small unit of money associated with the capitalist market economy, aptly symbolised the new greater dependence on lowly paid wage labour which obliged men to leave their sites of reproduction for extended periods.

In 1968, just when they had rebuilt their homesteads, they were resettled once again, this time a few hundred metres to the east, because the first stands were in an area where floods often damaged the low-water bridges. Instead of providing improved infrastructure, the authorities forced people to relocate once more, again without compensation. Insufficient provision of water remained a huge problem. This process of resettlement within the homeland area coincided with a stream of former farmworkers arriving from commercial farms in the area, adding to existing land pressure. Labour tenancy had been abandoned in the Tzaneen area in 1967, turning black farm dwellers into ‘squatters’ who had to leave once their farm-work contract expired. They could move only to places like Berlyn to find land to live on, and, together with those who had been forcibly resettled, had to diversify their livelihoods in the light of severely reduced economic opportunities (see Platzky and Walker 1985 for an analysis of the forced resettlements countrywide).

With the arrival of the new South Africa, the poor had high expectations of fundamental change, fired by the optimism spelled out in the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) (ANC 1994). But the government’s economic framework soon turned to a more conservative model with less of a developmental role for the state and more emphasis on the need for fiscal parsimony in the face of international pressure. The reorganisation of the country’s governmental and developmental architecture involved the destruction of the Bantustan administrations and the creation of municipal structures that would be responsible for local development. An unfortunate consequence of that reorganisation was the end of the subsidy system for border industries, including those based at Nkowankowa in the former Gazankulu. Their closure added to already high levels of unemployment in the area (van der Waal and Luiz 1998). The agricultural projects on Berlyn farm were also discontinued owing to their ‘Bantustan’ origin. While the old homeland development institutions were dismantled, the post-apartheid state put its own developmental programmes in place. The most important of these were the RDP housing programme, infrastructure development and the social grants system.

Against this historical background of settlement, dispossession, incorporation into the South African industrial labour system and the post-1994 transformation, we can now turn to the localised effects of and responses to the changes in the political economy. I will first focus on the changes in the demography and in the relationship between land, labour and reproduction, including the changing mix of multiple livelihoods, in the Berlyn settlement between 1986 and 2013.

Changes in demography and livelihoods

The population of the Berlyn settlement showed remarkable continuity in the period of fieldwork, relative to the rapid changes that characterise urban populations. Some individuals and a few families had left the settlement in order to look for better economic opportunities elsewhere, but mostly the same Tsonga-speaking (and a few Sotho-speaking) extended families that occupied clusters of stands in 1986 were still doing so in 2013, although the individual membership had, of course, changed. What about people from outside South Africa entering the communal rural areas? The war in Mozambique had led to a gulf of refugees entering the former Gazankulu from 1985 and by 2013 some of these were still around in Berlyn: a few had been incorporated through marriage or through providing labour and one polygamous Mozambican family was occupying two residential stands. The historical links between Tsonga-speakers in South Africa and Mozambique facilitated such incorporations. Occasionally a Zimbabwean refugee would pass through the settlement in search of work or to trade in recent years, but other than the Mozambicans, no people from other African countries had settled in Berlyn. Two traders from India had settled in the area in the last few years, each to run a credit-providing general store: one in the neighbouring Mulati and another in the new stands of Berlyn.

On the level of household changes, a comparison of survey data collected in Berlyn settlement in 1986 and 2013 reveals a number of important changes in the composition of households and associated livelihood strategies. What do these changes tell us about adaptations on the micro-level to changes in the larger context?

Significant points emerging from Table 1 indicate the following changes in the period 1986–2013:

The population of Berlyn settlement dropped by 25%, especially in respect of children.

The average size of households shrank.

The relative number of female-headed households increased substantially.

There was a 30% increase in the number of absent household members, with a steep increase in absent women.

Educational qualifications rose from a very low level to a low, but much improved, one.

| 1986 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of households | 58 | 60 |

| Total population | 372 (200 female, 172 male) | 279 (minus 93 = 25% decrease) (144 female, 135 male) |

| Children 0–14 | 170 | 76 (minus 94 = 56% decrease) |

| Female 15–64 | 108 | 95 |

| Male 15–64 | 79 | 88 |

| Female 65+ | 8 | 11 |

| Male 65+ | 7 | 9 |

| Average size of household | 6.4 (varies between 1–15) | 4.65 (varies between 1–13) |

| Female-headed households | 12 | 20 |

| Single-person households | 7 (3 male) | 5 (3 male) |

| Foster children | 16 | 12 |

| Adult absent (de jure) members | 34 (30 male, 4 female) | 46 (25 male, 21 female) = 30% increase |

| Education | Grade 12: 1 man, 1 woman; tertiary education: 1 man; no education: 70 | Grade 12: 13 men, 19 women; tertiary education: 7 men, 10 women; no education: 21 |

The decrease in population numbers and in the size of households can be linked to the trend for people to move away from larger households in an attempt to find work in the cities or towns and to become more independent economically. The decrease in household size is often the result of the ‘unbundling’ of extended-family households, when the members of these groups split up in order to access more residential stands and the opportunities for more economic independence and small-scale cultivation associated with them. This unbundling is also reported from Mundzhedzi in the north of Limpopo Province (Aliber et al. 2013, 162). The impact of HIV/AIDS also contributed to the smaller size of the population. The big drop in the number of children seems to point to fewer births per woman. Smaller households mean fewer dependants per wage-earner and could be positive if incomes and employment levels had remained stable. The marginally lower number of foster children may be an indication of an improved ability to support one’s own family members and partly a response to the child-support grant system introduced in 1998. Important changes took place between 1986 and 2013 with regard to women’s greater financial independence. There was a growth in the number of female-headed households, reflecting a combination of the increasing independence of women and the growing inability of men to support a family. The introduction of child-support grants and women’s greater freedom to participate in the labour market contributed to their independence, as was evident from the increase in female migrating wage-earners. Improved education levels are an important condition for improved opportunities for employment, but, as we will see, despite increased levels of education, male unemployment was higher in 2013 than in 1986.

Further changes with regard to livelihood options appear when one compares work, unemployment and various types of income (Table 2):

| 1986 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|

| Formally employed/unemployed, male and female | 45 men, 33 women formally employed; 30 men and 73 women unemployed (37.9% of the males and 67.5% of the females) | 30 men, 24 women formally employed; 47 men and 34 women unemployed (63% of the males and 42.5% of the females) |

| Migrants (formal and informal work) | 29 men, 2 women | 32 men, 20 women |

| Farm labour | 3 men, 16 women (of whom 2 men, 9 women in Berlyn agricultural projects) | 8 men, 13 women |

| Mining and industry | Industry: 9 men, 2 women Mines: 6 men Drivers: 5 men Shops and hospitality industry: 4 men, 1 woman Railways: 2 men | Industry: 8 men, 1 woman Drivers: 2 men Shops: 2 women |

| Security sector | Private security: 3 men Police: 2 men | Private security: 8 men, 1 woman |

| Other | Government: 6 men Domestic: 3 men, 2 women Shop-owner: 1 man Painter: 1 man | Government: 4 men, 3 women Domestic: 4 women |

| Income from social grants | 3 disability grants, 19 old-age grants @ R151 every two months | 26 old-age grants @ R1260 pm, 1 disability grant @ R1260 and 68 child-support grants @ R290 pm |

| Informal sector | Herding: 3 men Donkey cart transport: 3 men Building: 1 man Cattle farming: 2 men (both pensioners) Beer brewing: 10 women Craft production: 1 woman Healing: 3 men and 2 women | Herding: 3 men Donkey cart transport: 3 men (1 pensioner) Building: 3 men Tractor driving: 1 man (a pensioner) Selling food and sweets: 3 women Beer brewing: 1 woman (a pensioner) Craft production: 1 woman (a pensioner) Healing: 1 woman |

Significant changes in the period 1986–2013 are the following:

Substantially more women than men were unemployed in 1986. In 2013 the position was reversed.

Many men were still migrants in 2013. More women had become migrants. Women continued to work on Letaba Valley farms.

The higher level of male unemployment and lower level of female unemployment may be linked to improved education for women, the end of influx control, a reduction in the demand for unskilled male labour and the increased pressure on women to earn a wage if there is an insufficient male contribution. Changes in the global economy led to reduced demand for minerals and for unskilled labour, which had serious effects on male employment opportunities in the regional economy. While 9% of the migrant workers had been miners in 1986, there were no miners in the settlement in 2013. Fewer men found work in industries in 2013, indicating a change in industrial demand for unskilled labour, leading to the further exclusion of lowly educated men. More men found work on farms in the Letaba Valley in 2013, something they had tried to avoid before. Farm labour was, however, under pressure owing to the amalgamation of farms into larger units, higher capitalisation, and higher competition and mechanisation. In Limpopo Province as a whole there were 50% fewer farms in 2007 than in 1988 (Ibid., 14–18, 40). Jobs in the mining industry and in factories in Gauteng were similarly under pressure in an economy that was struggling to grow. These developments hit the most vulnerable part of the Berlyn population very hard.

Also contributing to employment changes in Berlyn was the fact that some families with access to better jobs had left the settlement in order to move closer to their place of work. Their stands were taken by people with low levels of education, moving from commercial farms into the communal area. More jobs in the security sector, especially with private security firms, had opened up and younger men in the settlement gravitated towards these. A close look at the labour histories of individuals shows the tendency to move regularly between jobs and the difficulties in securing permanent wage employment.

In contrast to the decrease in wage labour, state interventions impacted positively on the income of poor households. The pensionable age for men was lowered from 65 to 60 years (equal to that of women) and payments increased over the years. In addition, child-support grants were introduced for the children of poor parents, up to the age of 17. Even though the amount was relatively small (R290 per child per month in 2013), the grants improved the position of women, especially since support payments by male partners were often inconsistent.

A third source of income in Berlyn was the informal economy: it had decreased somewhat, but was still of vital importance to many households in 2013. Informal income generation was often combined with other forms of income. In comparison to 1986, there was less cattle farming, beer brewing and healing in 2013. Building work, herding work, donkey car transport and food sales were still of some importance. Illegal informal economic activities, usually associated with men, seem to have been more prominent in the period before 1994, including poaching and the sale of industrially produced alcohol, whereas criminal activities (theft and associated violence) were an increasing social concern in post-1994 Berlyn, as will be discussed.

Table 3 indicates a larger drop in livestock farming than the decrease in human population size would lead one to expect. This drop points to the fact that by 2013 much less was invested in rural livelihood activities. There were smaller numbers of cattle, goats and donkeys and fewer owners in 2013. Cattle owners were still mostly men with access to savings from migrant labour, building up herds during their working years to farm with after retirement. But these men were nearly 50% fewer in 2013 than in 1986 and most investment from migrant and other earnings had shifted to houses and furniture, even if building projects often stretched over many years. This shift to investment in shelter is corroborated by a study in another Limpopo rural settlement in which investment in housing relative to income was indicated as surpassing even middle-class norms (Ibid., 173). In 1986 there were many mud-brick rondavels with thatched grass roofs in Berlyn, but in 2013 walls were predominantly built of bricks and roofed with corrugated iron. Better housing conditions, resulting from higher investment in buildings, were evident in the 50% decline in the number of people per room between 1986 and 2013. In 1986 there was one ‘modern’ house that would have fitted into any middle-class area in an urban township, while in 2013 there were five such houses in the settlement, three of them roofed with tiles. Tile roofs indicated economic differentiation within the settlement, because building with such an expensive material required access to a consistent income.

| 1986 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|

| Livestock | 263 cattle (14 owners), 332 goats (39 owners), 63 donkeys (7 owners) | 117 cattle (8 owners), 41 goats (4 owners), 35 donkeys (4 owners) |

| Houses | 210 rooms for 372 people (1.7 persons per room), most roofed with grass | 298 rooms for 279 people (0.9 persons per room), most roofed with corrugated iron |

Despite the reduction in cattle and goat farming, investment in small-scale agriculture in the form of maize production and vegetable gardens continued, indicating a lowering in the relative importance of animal husbandry (a male-oriented livelihood) in relation to the stability of the production of maize and vegetables (a female-oriented livelihood). As in 1986, there were 15 households in 2013 that used their allocated fields, but only after good rains (Ibid., 22). Those using their fields were mostly older people who invested time and money in this high-risk enterprise. People mentioned that only small amounts of maize were reaped in recent years and that the last good season was in 2010–11. Surpassing the intermittent production of crops on fields outside the settlement was the annual planting of crops on every residential stand. Donkeys still pulled ploughs, but some people had saved enough money to hire a tractor. In addition, in 2013 many more households than in 1986 had a fenced winter vegetable garden on their stands.

In 2013, therefore, people were still producing food in the form of maize and vegetables on their residential stands, but the use of communal land for grazing had fallen dramatically and fields had become less important. In their increased dependence on money income, people had moved from being surplus-producing peasants-cum-proletarians in the 1940s to dependent wage-earners, supplementing their wage income from the informal economy (including subsistence production) by 1986. But this dependence on wage income was still mitigated by 2013 by the importance of multiple non-wage livelihoods dependent on a range of resources: some agriculture, free access to some land, the opportunities provided by the informal economy and the infusion of social grants. In addition, the continued process of economic differentiation has to be taken into account, as some families had been able to move out of the rural poverty cycle and could invest in an urban livelihood and education, enabling them to move out of the settlement or only nominally holding on to a residential stand where dependants looked after their interests. Authors such as Potts (2009) argue, however, that despite the general process of ‘de-agrarianisation’ in sub-Saharan Africa (Bryceson 1997), there is now also a slowing-down in the rate of urbanisation, leading to greater dependence on the informal economy and agriculture.

While incomes in Berlyn households may have improved, there were only three owners of motor cars and one tractor owner in 2013, while in 1986 there had been eight motor cars in different states of disrepair. One reason for this change was that male migrants had access to much more economical means of transport (in the form of the long-distance taxi industry) by 2013. In general, however, the economic situation in Berlyn had improved only marginally. Residents still had to rely on multiple sources of income, and unemployment was high among men. Individuals adapted to the new economic and political conditions by spreading the risk as far as they could, e.g. by moving to more promising areas for job opportunities and further training, and by accessing state resources such as education, social grants and improved infrastructure services. How have the changes in livelihoods affected social relations, those of gender, generation and governance in particular? What were the collective strategies that people in the settlement used to meet their needs in the post-1994 period?

Entanglement of livelihoods with relations of gender, generation and governance

Changes in gendered and intergenerational relationships were obvious in Berlyn in the period under study. An important causal factor for such changes on the local level in this communal rural area was the democratic culture that had entered South African public life in 1994. Women’s rights, for instance, were not only safeguarded on paper by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, but interventions to improve the protection of women made real positive impacts on their status. Consequently, there was a striking visible change in women’s behaviour in public meetings in Berlyn after 1994. In the 1980s women would sit silently on the ground to one side in community meetings at the headman’s place and would speak only when being addressed directly. In 2013 they were sitting on benches and chairs among the men and were more vocally present. Women were strongly represented in ward and headman committees and a woman was the chair of the local civic organisation. Women reported that physical violence in the home had decreased substantially and linked this to the heavy sanctions against intimate partner violence that had been introduced after 1994.

With increased employment for women, improvement in their level of education and the introduction of child grants, women in Berlyn and in the communal rural areas in general had more access to economic resources than in the past. Men were the main victims of the economic restructuring that had caused a huge reduction in circular migration to the mines and industries of the economic core of the country. In 2013 it was clear that something substantial had shifted: young men in Berlyn were in a much weaker position in terms of economic prospects and social standing than in the 1980s and 1990s. They no longer had the upper hand in community organisations. Many struggled to establish a household and build a family owing to higher levels of unemployment. In some cases they remained dependants in their parents’ households. Some engaged in excessive drinking and petty crime.

In the early 1990s young men of Berlyn had been politically prominent in the local politics of liberation. In the witch-hunts of the period of political upheaval before and immediately after the 1994 transition, the comrades had led violent attacks on prominent older people in the area, including the headman of Berlyn. Their idea was to cleanse the area of the evil associated with older people’s supposedly malevolent supernatural powers. Many of those identified as witches in the rural areas of the Limpopo Province were stoned and burnt to death as symbols of an old order that resisted the arrival of the future utopia. But soon after 1994 the ANC leadership had ensured that order was restored, that the power of traditional authorities (formerly known as ‘tribal authorities’) was strengthened and that political power was returned to older men (Niehaus 2000).

By 2010 there were widespread protests across the country about service delivery and the lack of police commitment to dealing effectively with crime (Alexander 2010). These reflected high levels of social insecurity, caused not only by crime, but also by the AIDS pandemic, unemployment, neglect by the state, and corruption. This situation was aggravated by the neoliberal policies that put constraints on state spending amidst high expectations of economic improvement. The shift from ‘witch-hunts’ to ‘thief-hunts’ in the Lowveld, as discussed by Niehaus (2012), reflected the social impact of these changing factors and was also visible in Berlyn in 2013. In the new outbursts of collective anger the targets were criminals, hunted down to be killed or beaten up. For the participants this served the purpose of getting rid of the new evil that haunted society, namely crime committed mostly by poor and unemployed young men. Times had changed in the eyes of a disenchanted population, and attempts to reach utopia were being undermined by these young criminals who, they said, needed to be punished. Events in 2013 in the Berlyn settlement reflected these insecurities and their gendered, generational and governance dimensions.

Thief-hunting and clashing with the police in 20132

In 2012 and 2013 several murders and rapes took place in the vicinity of Berlyn that were perceived to have been insufficiently investigated by the police. People said that bodies had been found with parts cut off, clearly a sign of the work of muti murderers who used negative supernatural power to harm fellow community members. At one point a woman was killed and another raped where they were collecting firewood. The survivor pointed out a prophet and healer in the community as the culprit. This prophet was suspected of giving protection to criminals and bribing the police. When the police questioned and then released him, the rumour spread that the police station at nearby Letsitele could not be trusted. A mob burnt the prophet’s cars and houses and chased him and his patients out of the area. Members of the community were charged with arson. Before the court case a memorandum comprising the complaints from the community was handed to the Letsitele police after a protest march by several thousand people. A few weeks later, the police met the community and a high-ranking police officer (a female brigadier) addressed the meeting from the back of a pickup van. Her vague references to the police’s commitment to continue investigating the matters made the crowd aggressive and she had to flee the scene.

Soon after this event, a woman reported a young man from a neighbouring settlement to the Berlyn headman for breaking into her house and stabbing her in the leg. She had first reported the case at the Letsitele police station, but as the police were unresponsive, people went to look for the man themselves. He was brought to the headman’s court when it was already getting dark on a Friday evening and alcohol and marijuana were contributing to a heady atmosphere amongst the crowd of about a hundred people. While he was being questioned, he was repeatedly hit by bystanders. Someone must have alerted the police because two police vehicles suddenly appeared but spun away when their windows and headlights were smashed by a rain of stones. Meanwhile, the suspect had argued himself into a corner and the mob became very aggressive. But he managed to escape in the ensuing scuffle. He was caught again, beaten unconscious, then dumped in the court space – bruised, bleeding and without a shirt – as if dead. The police reappeared in strong force – 12 vehicles with searchlights under the command of the regional police general. Many officers with guns on the ready got out while the crowd moved around restlessly in the searchlights. Eventually, the police entered the area and about an hour later an ambulance took the victim away. In the next days the police returned to take the headman in for questioning and to hunt down every young man they could find in the settlement. The accused made a court case against the community of Berlyn and demanded 600,000 South African Rands as compensation. Senior police officers advised the community to negotiate with the accused, who had managed to turn himself into a victim of vigilante action.

However, collective action in Berlyn has in recent times not only been directed against criminals; it has also been employed strategically to get access to resources managed by the state or to protest the neglect by the state in meeting community needs. It took some time before RDP houses began appearing in Berlyn (as urban areas had received priority), but by 2013 10 RDP houses had been built for the poorest households. The provision of water and electricity was improved nationwide, but local implementation was not a straightforward matter. In 1986 there were three hand-pumps in Berlyn, but they were often in disrepair. In order to address this problem boreholes were sunk in the immediate vicinity of the settlement, with the intention to pump water from the boreholes to nearby reservoirs. But continuous problems with the provision of diesel, the theft of water pumps and sabotage by frustrated users made this basic government service a perennial headache. Adding to these difficulties was the fact that some residents diverted water from the communal taps to their own stands by means of illegal connections that reduced the water pressure. Translating their frustration into action, residents targeted the local officials. Poor water provision in the settlement led to many accusations of neglect against the male water-pump attendants. The situation was highly gendered given that providing water, cooking and washing clothes for the household were seen as women’s work.

Berlyn was one of the last settlements in the Tzaneen Municipality to be connected to the electrical grid, as late as 2011. The common perception was that other settlements had been able to jump the queue because of corruption among municipal councillors and ESKOM (Electricity Supply Commission) officials. Nevertheless, the arrival of electricity in Berlyn was a great improvement, bringing electric lighting into every home and allowing people to use electrical appliances. Before 2011, electricity was tapped illegally from the local primary school and fed to a number of houses through izinyoka (‘snakes’, i.e. illegal connections) that were hidden a few centimetres underground. This was an example of opportunistic collective action aimed at accessing state resources.

An event in 2013, involving the mobilisation of community members, reflected the fierce jockeying for resources in a context where several settlements had to compete for development projects and capital allocations from national, provincial and municipal governments.

Twisting the arm of the province

This event followed from a survey and meetings organised by the provincial Department of Social Development. The survey indicated that Berlyn and its neighbour, Mulati, were poorly resourced and had the lowest income levels in the area. Residents from the two settlements were promised the allocation of an after-school centre involving the provision of a building, meals and several paid positions for care-workers. Meanwhile community members in another settlement started an initiative to provide food and supervision in the afternoons for children from single-parent households. Berlyn and Mulati residents initiated a similar project in the hope of strengthening their own claim. When the funds were allocated to the other informal ‘centre’, the officials from the district office were invited to a community meeting at a local church in Mulati. When the officials could not account for their decision satisfactorily, the well-attended meeting turned into a ‘hostage’ event. The officials were not allowed to leave without promising to provide an after-school centre to that area. The ‘hostages’ were sitting at one side, deeply humiliated. They were allowed to make phone calls, but could not reach their superiors. Late in the afternoon, they were released after signing a declaration admitting that the allocation of funds to another area had been wrong and that the decision would be turned around.

This illustrates the length to which residents of Berlyn were willing to go in order to force a decision in their favour. Whether this risky tactic would bear fruit was another matter, but it must have had an impact on the officials’ perception of the power of mobilisation from below. Another example of community action aimed at getting access to state resources was a land claim on Berlyn farm by senior members of families that had been forcibly resettled in 1963.

Land claim and contestation of the restitution

Just before the land claim submission period closed in 1998, a claim on the Berlyn farm was submitted by a group of men of whom most were related to the headman. In the claim they outlined the forced resettlement and their loss of property in 1963. The claim was accepted by the Land Claims Commissioner and a list of 200 beneficiary families was created. Some had moved elsewhere in the interim, but most were still living in Berlyn and nearby settlements. The amount the state eventually awarded as a restitution payment was contested by the claimants and the decision then went for review.

One member of the most prominent family had taken the initiative in lodging the claim. The fact that he lived in Johannesburg and was involved in national politics pointed to the importance of strong relations across the urban–rural divide and the usefulness of political connections in rural people’s quest for important resources. The Berlyn land claim process also underlined the continued interest of older claimants in land for agricultural purposes, while most of the younger ones were in favour of a cash payment.

Conclusion

The forebears of the people of Berlyn were driven into the Lowveld by natural pressures and war. By the 1870s mixed agriculture was still their main livelihood, supplemented by wages earned by stints of male migrant labour to the mines. Dispossession under colonialism and segregation denied black people the right to own land or to produce for the market. Their semi-peasant existence was destroyed and the population became increasingly dependent on male migrant labour. Under the policy of separate development the people living in Berlyn were vulnerable migrants-cum-farm workers who were forcibly relocated to the farm’s margins to make way for commercial farming followed by ‘development’ projects in the Gazankulu Bantustan. By 1986 most income was derived from male migrant work in the mines and industries.

A number of important changes in social experience and economic opportunities were evident in the life of Berlyn residents over the period 1986–2013, reflecting the changing political economy of the country as a whole and the Limpopo Lowveld in particular. Structures of dependence shifted away from migrant labour to the state’s social support of women and children in a context of de-agrarianisation. The effect of these changes was especially evident in gender and generational relationships and in various forms of collective action aimed at accessing state resources.

The transition to democracy in 1994 led to high expectations of employment creation, a developmental state and improved infrastructure. Although most of the expectations were not met as originally expected, education, housing, water and electricity did improve. By 2013 most families had improved their housing, all had access to electricity and all still planted maize and vegetables on their residential stands, but investment in livestock had diminished. Levels of unemployment among unskilled labourers in Berlyn had increased over the period under study. The dismantling of the Bantustan development infrastructure contributed to the loss of jobs. Men were hard hit by structural changes in the economy, including the reduction of work opportunities in mining. By 2013 men were taking jobs in the security and agricultural sector that they had shunned in the past. In contrast, the position of women had improved owing to better education, social grants and more freedom to move around. This increased their ability to enter the job market but also increased their vulnerability to male aggression arising out of frustrated attempts to access the job market.

Twenty years after the South African transition to democracy, Berlyn settlement remained a labour pool from which the most successful individuals tried to escape. Poverty levels were high and the high dependence on social grants was an indication of the lack of household independence. Unemployed young men were increasingly regarded as a problematic social category. Cases of theft, murder and rape led to outbursts of vigilante action directed at criminals. Collective anger in the form of ‘thief-hunts’ can be contrasted with witch-hunts during the liberation struggle, when elderly people were the main targets.

While individual livelihood strategies were aimed at diversifying sources of income, obtaining better education and extending social networks into the urban areas, collective forms of social action were directed at getting rid of criminals and accessing state resources. But local people’s relations with the state were fraught with contradictions. Diminished opportunities for labour migration had been offset, at least in part, by the introduction of the system of social grants as well as other state interventions. People in Berlyn acknowledged the positive effects of these interventions, but indicated that they also expected a democratically elected government to be more caring and involved in addressing their plight. Protest action and violence against the police, and holding local government officials against their will, were examples of community action in which people gave vent to their frustrations. The people in this area, as elsewhere in the country, now display a more independent position in relation to the state, particularly at the level of local government.

This investigation of the dialectics of multiple livelihoods and social relations in a rural Lowveld village, over several decades, provided a strong analytical basis for tracking larger tendencies that are embedded in the national and international political economy. One of the main observations that were made in this study was the increasing marginalisation of younger men who lacked the skills for employment in an economy moving away from its dependence on unskilled male labour. While many forms of local livelihoods continued to function in survival strategies across the period investigated, in a village that remained a poor rural backwater, the mix of these livelihoods and their gendered and generational dimensions made a huge difference in the social and economic realities of specific social categories, depending on the criteria of class, gender and age. For the people in the Lowveld rural villages, to escape a future of bleak employment opportunities and the associated social inequalities and frictions, their basic need for highly improved access to resources for production, municipal services and quality education will have to be met.