Since the middle of the 2000s, South Africa has experienced a growing wave of localised community protests around issues of state ‘service delivery’ (Alexander 2010).1 These protests have been increasingly characterised as ‘violent’. Private research outfit Municipal IQ, for example, cautioned that the evidence for 2012 ‘remains a worrying record, with a growing number of service delivery protests – over three quarters – being violent in nature’ (Municipal IQ 2013). Academic analysis has also pointed to protest violence. A research team from the University of Western Cape, for example, argued that ‘protests are not only increasing in frequency, but are also far more likely to turn violent’ (Visser et al. 2012, 5). Similarly, a research team from the University of Johannesburg found that ‘peaceful’ protests declined between 2008 and 2014, while ‘disruptive’ and ‘violent’ protests increased (Alexander, Runciman, and Ngwane 2014).

The relationship between violence and collective resistance is not a new problematic for South Africa. It was thrust to the fore during the apartheid era, with the African National Congress (ANC) turning towards armed struggle and residents seeking to make townships ‘ungovernable'. Contemporary community protests resemble these earlier struggles in that they are similarly rooted in poor black communities, and often draw from similar repertoires of collective action. Yet protest violence takes on new meaning in the post-apartheid context. Whereas under apartheid, black residents were excluded from any meaningful engagement with the state, in the contemporary period violence represents an alternative to formal democratic channels such as voting. Yet, while democracy and violence are often understood as antithetical modes of operation, as Von Holdt (2013a) argues, ‘democracy may configure power relations in such a way that violent practices are integral to them’ (590).

This paper unpacks the meaning of ‘violent protest’ by examining it from the perspective of the media, protesters and the state. Drawing from news articles, interviews with community protesters and statements by public officials, the analysis supports two interrelated conclusions. First, violence is an ambiguous concept that is used to represent different actions by different actors, and thus becomes open to a variety of moral arguments and political projects. Second, violence and democracy are deeply entangled. On the one hand, violent practices may become a tool of liberation, promoting democracy by empowering marginalised groups. On the other hand, democracy may become a tool of domination, constituting as violent those persons and actions that deviate from institutionalised norms. To lay the foundation for the analysis, I begin by examining theoretical propositions regarding the violence–democracy relation.

The deep entanglements of democracy and violence

In the South African context, the argument that democracy and violence are deeply entangled is put forward most forcefully by Karl Von Holdt (2013a). Drawing from an analysis of intra-elite conflict, he concludes that ‘South Africa is making the transition to violent democracy in which democratic institutions and forms, elite instability and violence sustain each other’ (602, original emphasis). Underlying this claim is the idea that, in the context of ‘deep poverty and extreme inequality’, democracy creates the conditions for the use of violence – including coercive and extra-legal tactics – to secure rents and the redistribution of resources. For Von Holdt (Ibid.), this violence ‘destabilises the symbolic order of democracy’ (596) but it does not lead to ‘systemic breakdown’ (590). Democracy and violence are thus opposing symbolic orders, but they are not mutually exclusive and they may, to a certain extent, enable each other.

While this analysis importantly shows that democracy and violence may coexist, despite their opposition, alternatively we may understand them as mutually constitutive. Von Holdt (2012, 2013b) hints at this deeper relationship in his other writings, and suggests that it may take two different forms. Based on this analysis we may identify two different perspectives on democracy and violence, with one organised around liberation and the other organised around domination.

Building on Von Holdt's engagement with the theorising of Frantz Fanon, the liberation perspective emphasises resistance from below. For Fanon (1963, 92–95), violence has inherent transformative potential because it enables participants to expunge feelings of inferiority, develop a sense of collective agency and strengthen their position with respect to leaders, who are forced to treat them as active rather than passive participants (Von Holdt 2013b, 116). According to this perspective, violence is emancipatory and radically democratic. Building on Von Holdt's engagement with the theorising of Pierre Bourdieu, the domination perspective instead emphasises ‘symbolic violence’, which Von Holdt defines as ‘the crucial mechanism through which social order, and the hierarchies and structures of domination it sustains, is reproduced over time’ (Von Holdt 2013b, 115). For Bourdieu, the democratic state is the locus of symbolic violence, holding together the social order through laws and customs. According to this perspective, democracy is itself an ‘imperceptible and invisible’ form of violence from above.

Ultimately, Von Holdt (Ibid.) finds both perspectives lacking, and raises doubt about whether democracy and violence are mutually constituted. While acknowledging that violence may be useful for disrupting entrenched power imbalances, he argues that Fanon is naïve for failing to recognise how violence begets more violence, undermining democracy by disempowering people and producing a ‘climate of fear’ (Ibid., 118, 126). At the same time, he argues that the South African state is weak, with limited capacity for symbolic violence. Rather than symbolic violence from above, he thus emphasises how communities undermine state authority by creating alternative moral orders from below (Von Holdt 2012, 2013b).

This assessment underestimates the deep entanglement of democracy and violence in post-apartheid South Africa. To further develop the liberation and domination perspectives, and thus uncover the entanglement, we must critically interrogate the meanings of both violence and democracy. For the former, we must recognise that violence is used to describe a variety of actions by different actors, and may therefore become a tool for different political projects. For the latter, we may elaborate the liberation perspective by distinguishing between procedural and substantive democracy, and we may elaborate the domination perspective by highlighting the association between democracy and apparatuses of discipline and security. I take each in turn.

Ambiguities of violence

Violence is a flexible concept that may refer to a variety of social processes. Von Holdt (2012, 2013a, 2013b), for example, uses it to refer to a wide range of actions: community protests, xenophobic attacks, intimidation by striking workers, community policing and mob justice, coercive control of legal institutions by state officials, assassination of political leaders, disruption of political party meetings and authoritarian policing. The ambiguities of violence are also evident in academic portrayals of protest violence, as illustrated by the following definition provided by the Multi Level Government Initiative:

Violent protests are defined here as protests where some or all of the participants have engaged in actions that create a clear and imminent threat of, or actually result in, harm to persons or damage to property. Thus, in addition to the more obvious indications of a violent protest (the intentional injuring of police, foreigners, government officials, the burning down of houses or municipal buildings, looting shops), instances where police disperse protesters with tear gas, rubber bullets or water cannons, where rocks are thrown at passing motorists, or tires are burned to blockade roads are protests that are also considered to be violent in nature. (Visser et al. 2012, 5)

Not only does this conflation of many different actions explain their finding of a high incidence of violence – 79% of protests in the first eight months of 2012 – but it limits the analytical value of the violence concept. Achieving greater precision with respect to the meaning of violence demands answers to two questions: first, what physical acts does it entail, and second, who is responsible for carrying out those acts?

In terms of the ‘what’ question, we may distinguish between three different types of actions that are often understood as violent. Perhaps the most common usage of the violence concept refers to interpersonal attacks, consisting of physical assault or intimidation by one individual against another. This may include rape and other forms of sexual assault, xenophobic attacks, police brutality and certain instances of mob justice. Rather than attacks against people, a second common usage of the violence concept refers to property destruction, including both private and public property. This type of act is frequently associated with community protests, which sometimes include the burning of buildings and vehicles. Protests also commonly involve a third type of action that is analytically distinct from the other two because it does not include attacks against individuals or property. This type of act may be referred to as social disruption, and includes any action that challenges or ‘harms’ the existing social order or patterns of everyday life. In community protests this often takes the form of road barricades that block traffic.

Each of these types of actions may be carried out by different actors. In the case of community protests, however, certain actions tend to be associated with particular actors. Whereas property destruction typically results from the actions of protesters, the police have been more responsible for interpersonal attacks that result in death. Between 2004 and 2014 the police killed more than 50 protesters during community protests (Alexander et al. 2014).2 Further, the legality of an action depends heavily on where the actor is positioned in relation to the democratic state. Because the state tends to monopolise the legitimate use of force, actions by the police are commonly (though not always) treated as legal. Conversely, interpersonal attacks, property destruction and social disruption initiated by protesters are often identified by the state as illegal, with the consequence that notions of violence and illegality are often used interchangeably.

Unpacking the meaning of violence thus requires attention to both what is being done and by whom. But it is also important to distinguish between what Galtung (1969) refers to as direct violence and structural violence. Whereas direct violence refers to actions committed by identifiable actors, and would include the three types described above, structural violence refers instead to the organisation of social relations and its attendant inequalities of power and resources. Though structural violence is often less visible, it commonly results in substantial physical harm (Farmer 2004; Therborn 2013). It is also closely linked to notions of symbolic or cultural violence, which refer to the cultural or ideological contexts that justify or legitimate harmful social structures (Galtung 1990; see also Von Holdt 2012, 97).

This distinction is crucial for both perspectives on the violence–democracy relation, each of which posits a different relationship between direct violence and structural violence. The liberation perspective emphasises the way in which collective actors may use direct violence to oppose structural violence, thus promoting what we will refer to as substantive democracy. The domination perspective instead underscores how discourse around direct violence, and particularly the way in which it violates what we will refer to as formal or procedural democracy, reinforces structural violence by justifying and legitimating the repression of dissent. Before turning to these two perspectives, I first ask: how prevalent are these different usages of the violence concept?

Representations of violence

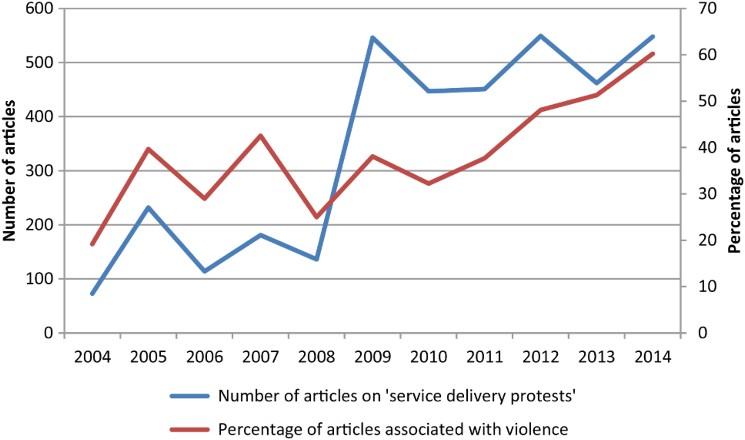

Given their prominent role in shaping public discourse, it is especially important to examine how news outlets represent violence. Duncan (2014a) argues that media outlets prioritise reporting on violent protests over non-violent ones, and that ‘journalists continue to repeat the chime “violent service delivery protests” even in cases where it is not warranted’. It follows that the proportion of articles on community protest which refer to violence increased dramatically between 2010 and 2014 (Figure 1). To better understand how violence is represented in the media, I examined the types of actions that were described as violent in four major newspapers – The Star, Business Day, Sowetan and The Citizen – between 1 January 2014 and 30 June 2014, including a total of 85 articles. The results are presented in Table 1.

Number of news articles on community protests, and percentage associated with violence, by year. Source: SA Media online database (see http://www.samedia.uovs.ac.za/index.html). The reported counts include all sources in the database. Articles on protest include those articles containing both ‘protest’ and ‘service delivery’ in the full text. The percentage of articles associated with violence includes those containing either ‘violence’ or ‘violent’ in the full text. The 2014 figures are based on the first six months of the year (January through June), with the number of articles extrapolated to a full year by doubling the actual number.

| Action attributed to the concept of violence | The Star | Business Day | Sowetan | The Citizen | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unspecified | 52.0 | 66.7 | 53.3 | 54.2 | 56.5 |

| Property destruction | 48.0 | 42.9 | 60.0 | 41.7 | 47.1 |

| Police brutality | 32.0 | 23.8 | 13.3 | 20.8 | 23.5 |

| Social disruption | 20.0 | 28.6 | 13.3 | 12.5 | 18.8 |

| Interpersonal attacks (by non-state actors) | 16.0 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 20.8 | 12.9 |

| Public violence arrest | 8.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 8.3 | 8.2 |

| Looting of shops | 4.0 | 4.8 | 13.3 | 4.2 | 5.9 |

| Number of articles (N) | 25 | 21 | 15 | 24 | 85 |

Source: SA Media online database (see http://www.samedia.uovs.ac.za/index.html), author's analysis. The categories are not mutually exclusive, as one article may represent violence in multiple ways. The columns thus add up to more than 100%.

The most common representation of violence is an ambiguous one, where violence is left unspecified. In 57% of the articles, violence is not attributed to a specific action but rather used as a general descriptor of the protest. In these cases it is left up to the reader to determine the precise meaning of violence. Many of these articles draw from reports by police, academics and private research outfits to argue that violent protests have been increasing. For example, one widely cited statistic is based on a February report by the Gauteng Police Department, which claimed that 122 of the 569 protests in the previous three months were violent. Yet the statistics are commonly adopted uncritically, without any explanation or interrogation of how violence is being defined. In other instances, the label of violence is applied to protests without any statistical evidence, often with the intent of identifying a concerning trend:

Protest action, sometimes violent, and often instigated by people exasperated by a lack of service delivery, has long marred Gauteng's townships. (Magubane 2014)

Parts of the country have been engulfed by violent protests – and in some cases lives were lost. (Tau 2014)

Both statements express concern about protest violence without specifying what violence entails. While the latter statement does allude to the loss of life, the article does not specify who is dying, how they are dying or who is responsible for the deaths.

The second and fourth most common representations of violence refer to actions by protesters. Nearly half of the articles (47%) use the violence concept in reference to property destruction. The following statement, for example, attributes the aforementioned police statistic to the burning of public buildings: ‘Community centres, libraries, clinics, halls and even police stations have been attacked in 122 violent protests in the past three months, peaking at five a day this week’ (Ndaba 2014). Property destruction has become one of the most controversial aspects of community protests, and in turn is a primary focal point in news articles on protest violence. Though somewhat less often, violence is also commonly used to describe acts of social disruption such as the barricading of roads or the burning of tyres. An article in The Star, for example, reports: ‘Fifteen people appear in Kuruman Magistrate's Court after a violent public service delivery protest saw the closure of the N14 road to the town’ (Van Schie 2014). The representation of violence as social disruption occurred in 19% of the articles.

The third most common usage of the violence concept, appearing in nearly one-quarter of the articles, are references to police brutality. This illustrates that actions by the state may also be represented as violent. Yet it also reflects the fact that January 2014 saw an especially high number of police killings, with seven protesters killed by police during protests in Mothutlung, Roodeport and Tzaneen (Alexander et al. 2014). Had the analysis excluded the first two months of 2014, this usage of violence would have been significantly less common. Further, it is important to note that instances of police violence are often referred to ambiguously, as in the statement above that refers to ‘loss of life’ without identifying the actors who are responsible.

Finally, there are three usages that only appear in a small number of articles. Thirteen per cent of the articles use violence to represent interpersonal attacks by non-state actors, such as protesters throwing stones at motorists, being attacked by other community members or intimidating foreign-born shop owners. Eight per cent of the articles refer to arrests for ‘public violence’. This usage begins to reveal how violence discourse may be used to repress dissent and maintain order, which is central to the domination perspective elaborated below. Finally, six per cent of articles represent the looting of shops, often owned by foreign-born residents, as violent.

This analysis affirms the ambiguity of violence, which may be portrayed in many different ways and is often presented without definition or interrogation. This ambiguity, in turn, leaves violence open to a variety of moral arguments and political projects. It is also important that these usages of the violence concept focus, almost exclusively, on instances of direct violence rather than structural violence. This emphasis sets the stage for the dynamic interaction between protesters and state officials, each of which similarly tend to associate violence with its more direct forms. Whereas for protesters, violence may become a tool of liberation, for state officials, violence may become a tool of domination.

The liberation perspective: violence promoting democracy

Fanon's theory of revolutionary violence was based on an analysis of colonial society. For him, the violence of colonial rule, which was explicitly racist and authoritarian, necessitated violent resistance:

The violence of the colonial regime and the counter-violence of the native balance each other and respond to each other in an extraordinary reciprocal homogeneity … The development of violence among the colonised people will be proportionate to the violence exercised by the threatened colonial regime. (Fanon 1963, 88)

Contemporary community protests in South Africa, however, take place in the context of post-apartheid democracy, rather than authoritarian rule. To fully appreciate Fanon's relevance for the contemporary period, therefore, we must unpack what it means to be revolutionary in the formal democratic context.

As with violence, democracy has multiple meanings. Zuern (2011), for example, elaborates a distinction between procedural democracy and substantive democracy. In the former definition, democracy includes formal institutions that secure basic civil and political rights. Most important here are the institutions associated with voting and electoral representation. Alternatively, the latter definition emphasises the importance of both socioeconomic rights and popular participation, including protest. In this view, ‘democracy is not a set of institutions but a process of continued contestation’ (Ibid., 17–18). In short, whereas procedural democracy is about the quantitative extension of civil and political rights, substantive democracy is about the qualitative meaning of those rights for material well-being and participation in decision-making.

One implication of this distinction is that protests may be simultaneously for and against democracy. Formal democracy creates inequality by distributing resources and political authority, empowering some while disempowering others (Von Holdt 2012, 94–96). This is evident in post-apartheid South Africa. The democratic state provides full voting rights and freedom of speech to all citizens, regardless of race. But these rights go hand-in-hand with persistent poverty, expanding income inequality and the continued exclusion of the vast majority of poor citizens from direct state decision-making. Frequently directed at the local state, community protests challenge this exclusion by demanding both recognition and the provision of resources. In this sense they may be understood as simultaneously challenging procedural democracy and promoting substantive democracy.

Different meanings of democracy are also intimately linked to different meanings of violence: whereas formal or procedural democracy is the opposite of direct violence, which is typically treated as illegal, substantive democracy is the opposite of structural violence, which undermines well-being and political participation.3 Direct violence may thus be radical and democratic, despite being illegal, if it opposes structural violence. There are strong echoes of Fanon's revolutionary violence in community protests. Whereas in his analysis violence was a response to the brutality of colonial rule, in contemporary community protests direct violence is one way to challenge the structural violence that is reinforced by formal democracy.

To illuminate this dynamic, I draw from 45 interviews conducted between July 2013 and July 2014 in three protest-affected areas, all within one hour of Johannesburg: Bekkersdal, an older township on the West Rand that now has an adjacent informal settlement; Motsoaledi, an informal settlement in Soweto; and Tsakane extension 10, an informal settlement on the East Rand. The interviews primarily include activists and those involved in protests, but also include residents with little connection to protest. They are not necessarily representative of the views of all protesters in these places, but they do reveal important insights regarding violence, protest and democracy.4

In April 2013 there were a series of protests in Motsoaledi. They included road barricades, the toppling of a traffic light and the burning of a KFC restaurant. As one community leader explained, property destruction and social disruption by stopping traffic were a last resort to get political officials to listen:

You know what happened, we had nine peaceful marches … then it's when we started to protest now, saying we have been peaceful for nine times and these people are not hearing us. When we want meetings for the Councillors and Mayors just to come and see us, and see how is the progress, so there's nothing they were doing to us like that. So these guys, the only language they understand is protest. Getting the freedom you want is all about striking so you know what, we started to make protest and everything. Then after that they came to us and listened to us. (Interview, 22 July 2013, male, 30s)

Though the community leader does not explicitly refer to violence, he does use the concept of ‘protest’ to denote something that is the opposite of ‘peaceful’. Elaborating on the distinction, two other participants in the protest explicitly contrast a ‘violent protest’ with a ‘peaceful march’, which involves an appeal to formal democratic channels through the delivery of a memorandum of demands. For them the use of violence is crucial for achieving attention:

Respondent 1:We were having something like nine peaceful marches that we conducted. Nobody is speaking about those ones. They are only speaking about KFC [which was burned down].

Respondent 2:They do not care. Nobody will come there. What they can do, they can send a puppet and say go take that memorandum and put it in the dirty bin. But when you go violently –

Respondent 2:The people started arriving; now the statement is being heard by many people. (Interview, 22 July 2013, both male, both 30s)

The notion of violence is used here as a synonym for social disruption – of the kind that requires the state to do more than simply send a ‘puppet’ official to receive a memorandum – though the mention of KFC suggests that it also includes acts of property destruction. Another resident who was also active in the Motsoaledi protest expressed a similar sentiment by contrasting a ‘march’ and a ‘strike’:

A march is legal. Because a march you go to JMPD [Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department] and they assist you and you are guided or accompanied by them… Strike is illegal… A strike is based on ‘where are we gonna march to and what are we going to destroy?’ So that they may be able to see what we want and that we serious, we need these things. A strike is more emotional. It's like guys, ‘we want these things and we are really tired now. We are demanding. So you have to see that we serious’. As you can see previously that KFC has been burned down, and if they do not see the demands of the people right now, I promise you the next [place to be burned] is Bara Mall, and a lot of people are going to get arrested and shot. But they do not care. They gonna fight till the end. (Interview, 16 September 2013, male, 20)

According to this analysis, a ‘march’ is a relatively benign and entirely legal affair. By contrast, a ‘strike’ is illegal and involves the destruction of property. It expresses a greater sense of urgency and a more forceful demand for recognition. For this resident, disruptive community protests are much more effective than voting, which tends to have a limited impact:

So there are a lot of political parties that are trying to move their way in, because it's election time. Where were they all this time? Where have they been hiding? When it's elections, they pop up … So that's why I don't like voting. I don't see the need … you need my vote, but you don't do anything for me … as long as they don't meet the requirements of the community, why? Why should we go and dirty our IDs? I don't see the reason. (Interview, 16 September 2013, male, 20)

Further pointing to the futility of voting, another Motsoaledi resident highlighted the empty promises of politicians and their failure to provide jobs and housing. For her, this is what led the community to protest and burn down the KFC:

Why vote? They make us fool … It's their lives that get better… [but] you, you are stuck here in the zozo [tin shack] for the rest of your life … Now I will never bother to use my ID again to vote. Forget! I will never, because … we vote for something that is not going to happen. They are full of lies, all of them. No one [party] is better than the other. You can come with a story today, say ‘vote for me tomorrow I will give you job'. There's no job and still people are still suffering … You see they open KFC but they never hire people who stay here. They bring their own people, while people who stay here, they are suffering … Why did they bring KFC when there's no houses here? They bring food, they must bring houses first … you can't bring a nice shop in the shacks. (Interview, 22 July 2013, female, 30s)

A common theme running through these reflections is the idea that formal democratic institutions are ineffective at either facilitating engagement or providing resources. In short, procedural democracy does not lead to substantive democracy. It is likely that this disconnect is tied to growing rates of voter abstention: in the 2014 national elections there were roughly 14 million eligible voters who did not vote, compared with only 11.4 million who voted for the winning ANC (Schulz-Herzenberg 2014). In this context, disruptive protests become a more effective way for communities to express their grievances.5

Similar dynamics were evident during a March 2014 protest in Tsakane, where residents burned tyres and barricaded the road for two reasons. One reason was to prevent taxi drivers from coming in to pick up workers. Community members had decided that the protest would be a ‘strike’ or a ‘stay away', which meant that residents should forego work in order to participate in the protest. The second reason was to garner the attention of local politicians:

Sometimes it is better if we scare them a little because if we marched relaxed they will think we are not serious. If we twist a little they will see that we are serious. Like in North West, when they protest, they do not apply and they burn tyres and do all those, but they get the response fast. But we apply before we march and they do not reply to us. But during elections, when they recruit us to vote, and after that they go and fold their arms. But when we have needs, they do not help us, but we vote. (Interview, 23 April 2014, female, 32)

For this leader it is more effective to have unprotected marches and burn tyres than it is to engage formally through legal marches or voting. Another protester from Tsakane expressed a similar sentiment, arguing that people are no longer content to simply wait for formal democracy to deliver on their basic needs. Tired of waiting for negligent politicians, he suggested that community members had decided to use ‘force’ to assert their demands:

It shows … the office for the mayor that we are tired … That is why we are burning the tyres, and put the stone in the middle of the road, just to show that the people are tired. So we need our needs in a force. Actually, we use the force. (Interview, 23 April 2014, male, 40s)

Violent tactics – most notably property destruction and social disruption – are thus a response to the failures of formal democracy. At the same time they may also be a response to the heavy hand of the democratic state. Indeed, evidence suggests that police actions often provoke protesters to engage in actions that are labelled as violent (Alexander et al. 2014). This dynamic was evident in Bekkersdal, where frequent protests between September and November 2013 often led to stand-offs with police. When asked about how protests became violent, one community activist offered the following explanation:

You know what happens? Sometimes we take peaceful marches without petrol bombs and things like that. But then cops start shooting at us, pah pah pah. When you start shooting at people who are not fighting, what are you implying? That's when the war erupts. But all in all we would not be fighting with the police, we would be going to the municipal offices. So here in Bekkersdal it's the policemen that provoke the crowds because they think they always have authority. (Interview, 12 March 2014, male, 28)

According to this analysis, the community sought to engage in ‘peaceful’ protest, but the police response provoked them to engage in more disruptive activity such as blocking the roads with stones. Another protester explained: ‘The police were shooting at the residents. So in terms of barricades, we must close the roads, because we don't want to see any movement of police cars’ (Interview, 12 March 2014, male, 33).

During one of the Bekkersdal protests, a large group of thousands began to march to Westonaria Municipality but they met a police blockade along the way, preventing them from leaving the township. Frustrated protesters then proceeded to burn and vandalise several public buildings. As one protester explained, the police blockade and burnt buildings were closely linked:

Interviewer:So let's say the police had just decided to let you go [continue the march to the municipality]. Do you think those buildings still would have gotten burnt down?

Protester:I can say definitely, none of that thing could have happened. Because [before the police blockade] people went through those halls without breaking anything. It was just a march to go to town. But the police blocked us, to say, ‘no, you are not going there’. People were not going to burn anything. But ever since the police started to fire the shots to them, and to start firing the tear gas to people, that's what made people angry, to say, ‘we are going to burn these facilities because they belong to the municipality’. (Interview, 12 June 2014, male, 21)

Based on this analysis, property destruction by protesters was a direct product of police aggression. For some residents, this aggression represents the state's unwillingness to engage with the community. Another protester explained the very same event as follows: ‘They don't want to listen to us. Yeah. We wanted them to come, or wait there, because we were going to them. So they, they don't take us seriously’ (Interview, 6 May 2014, male, 31). In this sense, voting and policing are simply two sides of the same coin, reflecting the inability of the formal democratic state to deliver substantive democracy.

The domination perspective: democracy promoting violence

The distinction between procedural democracy and substantive democracy also lays the foundation for the domination perspective. Rather than violence promoting democracy, this perspective highlights the way in which democracy promotes violence. This occurs in two ways. First, procedural democracy enables the differentiation of actions into those that adhere to formal institutionalised channels and those that do not. Whereas the former are commonly understood as non-violent, legal and orderly, the latter are prone to be labelled as violent, illegal and disorderly. The institutionalisation of dissent thus enables a discourse around violence. Second, formal democracy reproduces structural violence, most notably by undermining dissent.

The domination perspective emphasises what Foucault (1995) refers to as disciplinary power. Exercised rather than possessed, disciplinary power is a combination of two central processes: hierarchical observation, including the surveillance of individuals and their behaviour from above; and normalisation, including the ranking of behaviours and the administration of punishment (and reward) to bring deviant cases into line. In short, ‘apparatuses of discipline function through practices of prevention, correction, and enforcement and hence disciplinary surveillance functions to identify breaches of codes, incorrect conduct, lapses in self-control, and so on’ (Deukmedjian 2013, 54). For Foucault there is a close connection between disciplinary power and knowledge, which creates new norms against which behaviour may be measured and evaluated. In this case the new form of knowledge coalesces around the opposition between formal democracy and violence: the more community protests deviate from institutionalised channels and the law, the more likely they are to be labelled as violent actions that must be corrected or eliminated.

The disciplinary implications of violence discourse are evident in the positions put forward by state officials, such as those by President Jacob Zuma in his 2014 State of the Nation Address. While arguing that ‘loss of life at the hands of the police in the course of dealing with the protests cannot be overlooked or condoned’, ultimately Zuma is concerned with the culture of violence amongst protesters:

Violent protests have taken place again around the country in the past few weeks … when protests threaten lives and property and destroy valuable infrastructure intended to serve the community, they undermine the very democracy that upholds the right to protest … The police are protectors and are the buffer between a democratic society based on the rule of law, and anarchy. As we hold the police to account, we should be careful not to end up delegitimising them and glorify anarchy in our society. The culture of violence originated from the apartheid past. We need to conduct an introspection in our efforts to get rid of this scourge. (Zuma 2014a)

In this statement Zuma establishes an opposition between democracy and violence: the former is associated with the rule of law, while the latter is associated with anarchy. Despite the recent spate of police killings, he also affirms the legitimacy of the police as defenders of democracy, and suggests that protesters ‘threaten lives’. Violence is thus preserved as a descriptor for protesters, but not the state.

The disciplinary effects of violence discourse often operate through the conflation of very different acts, such as property destruction by protesters and brutality by police. Reporting on Gauteng Premier Nomvula Mokonyane's State of the Province Address, a 2014 provincial government newsletter thus remarks:

In the past few weeks Gauteng has been affected by an increasing number of violent public protests, some of which led to losses of life and damage to property. We condemn the loss of lives and the destruction of personal property during such acts. We therefore call on our communities to find reasonable means of engaging government through the legal channels provided for by our constitution. (Dlamini et al. 2014).

Making no mention of the fact that the ‘loss of life’ was largely at the hands of the police, this statement essentially uses police brutality to further demonise protesters as violent and unreasonable. In contrast, the accepted forms of dissent are those that operate through legal channels.

In February 2014, Mokonyane established a task team ‘to urgently address violent protests in the province’. The task team pleaded with communities to ‘follow proper procedures before embarking on a protest action’. These procedures include taking grievances up the chain of bureaucratic command, beginning with the ward councillor and if necessary moving up to the municipality, the Department of Cooperative Governance and, eventually, the Premier's Office. In this instance, violence is constructed in opposition to both the law and formal democratic procedures of grievance handling (Gauteng Office of the Premier 2014a).

For those communities determined to protest, the task team also encouraged residents to ‘follow the rules stipulated in the Regulation of Gatherings Act before embarking on protest action’ (Gauteng Office of the Premier 2014b). This includes providing written notice of the protest to the local council, which may deny the right to protest. Evidence suggests that municipalities often do deny permission to protest, or place conditions on protests that are difficult to meet (Duncan 2014b). In some municipalities, for example, protesters must first obtain permission from the authority that they are protesting against. Municipalities have also required community members to engage with local state officials before they could obtain permission to protest. Finally, permission to protest may be denied on the grounds that it is likely to become violent. These restrictions illustrate the disciplinary effects of procedural democracy, which both dampens dissent and lays the foundation for characterising protests as violent.

The ANC likely plays a contradictory role in relation to these dynamics. There is some evidence that party organisation and factional struggles at the local level exacerbate protest action (Von Holdt 2013a, 598–599). Yet the ANC may simultaneously reinforce the state's disciplinary discourse around violence. In a February 2014 radio interview regarding community protests, for example, the then ANC Provincial Secretary of Gauteng, David Makhura, remarked:

This violence de-legitimises issues of concern which communities raise that government has to respond to … hence the need for a more comprehensive response that seeks to educate communities that destruction of community property such as clinics, libraries and community halls takes us back … It is usually young people who are drawn into these protests and some are unemployed, while others come drunk. (Tau 2014)

This analysis uses the notion of violence to portray protesters as deviant, thus reinforcing the position taken by the Gauteng Provincial Government. Makhura also associates protest violence with youthfulness, drunkenness and unemployment, hinting that the protests reflect a broader pattern of ill discipline.

Violence is also entangled with what Foucault (2007) referred to as governmentality, which refers to a ‘power that has the population as its target, political economy as its major form of knowledge, and apparatuses of security as its essential technical instrument’ (144). Whereas discipline is about correcting individual behaviour and maintaining order, security is about managing and providing for the well-being of populations. For Foucault, apparatuses of discipline and security are overlapping. But the latter are especially crucial for liberal forms of government, where state interventions are justified as a response to threats against the population. Following on this insight, Buzan, Waever, and Wilde (1998) emphasise the importance of ‘speech acts’: the discursive identification of threats which in turn justify extreme countermeasures and rule-breaking.

From this perspective, violence may be understood as a discursive tool that state actors use to identify threats, justifying the repression of protest and extreme use of police force. In 2013, for example, President Zuma notified the country that he had instructed the Justice, Crime Prevention and Security Cluster of the state to ‘put measures in place, with immediate effect, to ensure that any incidents of violent protest are acted upon, investigated and prosecuted’ (Zuma 2013). Addressing parliament on the question of community protests, State Security Minister Siyabonga Cwele later affirmed:

We now have a plan and are ready to deploy the full capacity of the democratic state to identify, prevent or arrest and swiftly prosecute those who undermine our Bill of Rights by engaging in acts of violence. The ‘Eye of the Nation’ is watching. (Cwele 2013)

Violence is thus a tool for both discipline and security, simultaneously correcting residents who deviate from formal democratic procedures and neutralising threats in the form of protest. This was made clear by the Minister of Police, Nathi Mthethwa, in a January 2014 address to a police conference on public order policing:

In fact, if the protests are peaceful, orderly and non-violent, there would be no need for police presence at these protests. We need to underscore the point that whereas the Constitution permits unarmed and peaceful protests, the abuse of this right becomes a serious matter when participants take up arms and use unnecessary violence, which requires urgent attention and action from SAPS [South African Police Service] … Research conducted supports this indicating a significant increase in the proportion of mass gatherings that turn violent. This then requires that the police have the ability of the police to effectively manage these situations. (Mthethwa 2014)

By identifying protests as violent – as opposed to ‘peaceful, orderly and non-violent’ – Mthethwa justifies ‘urgent attention and action’ from the police. This construction of security threats, through the discursive usage of violence, is often interwoven with what Dorman (2006) has referred to as ‘liberation discourses’: a phenomenon whereby postcolonial governments appeal to their historical role as agents of liberation, and the only legitimate force of revolution, in order to shut down oppositional forces. Notions of violence may thus be used to counter dissent, justifying ‘immoderate responses from government in the form of political marginalisation, censorship and, in the worst cases, state repression through police brutality’ (Beresford 2014, 302–303).

The intermingling of discourses around violence, security and liberation was illustrated by new State Security Minister David Mahlobo in his 2014 address on the budget vote. Activating the liberation legacy, he outlined a plan for taking forward ‘our second phase of the transition as espoused in the National Democratic Revolution'. This included, among other tasks, the need for the State Security Agency to ‘curb violent protest action that threatens both domestic stability and authority of the state’ (Mahlobo 2014). In a written response to Parliament on questions regarding community protests, President Zuma, similarly but more broadly, referred to the well-being of the nation:

Addressing the volatile situation of protests, I have on numerous occasions called for restraint … We cannot solve our problems through violence and anger. This is something that we must address at all levels of society as part of nation building and promoting social cohesion and progress. (Zuma 2014b)

Thus far the security-oriented response of the state has failed to eliminate disruptive community protests. But the heavy hand of the police may nonetheless begin to have a ‘chilling’ effect. One Motsoaledi resident, for example, explained that he did support the protest but was deterred by fear of the police: ‘Oh no! I did not go there. I am scared of the police so I cannot go there’ (Interview, 31 October 2013, male, 25). Another Motsoaledi resident expressed a similar sentiment:

Respondent:I am scared! I'm scared of the police, yeoh!!!! The police, if they came here, yeoh!!! They hit us. No, I'm scared. Yeah, I'm scared. (Interview, 28 September 2013, female, 35)

These reflections suggest that resistance could be even greater if the state was less forceful in its response. The irony is that such force may be justified by labelling protests as violent.

Conclusion

As community protests continue and notions of ‘violent protest’ proliferate, it is increasingly important to sharpen our analysis of protest, violence and democracy. It is insufficient to treat violence and democracy as opposing or irreconcilable modes of action. This view fails to capture both the way in which violent tactics promote democracy, and the way in which democratic structures constitute people and actions as violent. At the same time, however, the supposed opposition of violence and democracy lays a foundation for more sophisticated analysis of the violence–democracy relation. Indeed, both the liberation perspective and the domination perspective understand violence as the antithesis of formal democracy.

The key difference between the two perspectives is the focal actor. The liberation perspective focuses on protesters. For them, direct violence – destroying property, burning tyres, barricading roads – represents an alternative form of democratic participation that is significantly more effective than following the formal channels created by the democratic state. In contrast, the domination perspective focuses on the state. For state officials these same acts are illegal and immoral, precisely because they undermine formal democratic institutions. In the case of South Africa's community protests, notions of violence thus lie in between two competing forces: one from below and one from above.

Lying beneath this tension is a complex interplay between action and discourse. In media outlets the concept of violence is used to represent a wide variety of actions, from interpersonal attacks to property destruction to social disruption. It is also commonly presented without definition or explanation. To the extent that notions of violence demand attention, these ambiguities may assist protesting communities in their struggle for recognition. Yet because violence has an inherently negative connotation, largely owing to its association with harm and disorder, it is difficult for protesters to give violence a positive moral valuation. For protesters the label is perhaps less significant than the actions themselves, and in particular their capacity for disrupting the status quo.

For the state, however, violence is an important discursive tool that may be used for governance and control. The more ambiguous the meaning of violence, the more flexible it is and the greater potential leverage it offers. Through the concept of violence, for example, protests where residents only burn tyres may be lumped together with protests where residents destroy property or throw stones at motorists. They may also be lumped together with protests where the primary violent act is police brutality. The conflation of different forms of violence enables the state to raise alarm, demonise protesters and justify repressive responses. Media outlets support this mechanism of discipline and security through their own ambiguous representations of violence, developing an empty concept that may be wielded by state officials.

The tension between protesters and the state raises key questions around the popular legitimacy of violence in the post-apartheid context. The evidence above shows that acts of property destruction and social disruption hold some popular legitimacy. But how widespread is this support, and how does it vary across social groups? Do non-protesters in township communities, or middle-class residents in the suburbs, view them as legitimate methods? Likewise, to what extent is there popular support for brutal police repression? Does this support decline when police kill protesters? Finally, how does popular support vary by political party affiliation? To what extent do political parties instigate or foment direct violence, either by protesters or the police? Answering these questions will be useful for further unpacking the meaning of violence in South Africa's contentious democracy.

As analysts, however, we must be careful not to use the notion of violence uncritically. It is a complex concept with serious political implications. A critical analysis thus requires careful attention to the different meanings of violence – including vague usages with no clear definition – and the way in which they become infused with moral meaning and applied to political projects. Indeed, it may be the case that the concept of violence is more distracting than useful, directing attention away from crucial issues such as power, social and economic injustice, and collective struggle. For this reason, critical scholars may choose to avoid the notion of violence altogether and search for more precise analytical concepts.